“The best time to buy real estate is five years ago.”

– Anonymous

“A pessimist sees difficulty in every opportunity; an optimist sees the opportunity in every difficulty.”

-Winston Churchill

As a stickler when it comes to protocol, please allow me – on behalf of the entire Clear Capital team – to comply with the Style Guide for Fourth Quarter Investor Newsletters, by passing along our best wishes for the coming year. I hope that the holiday season was a joyous one for you and your families. Last year was a record-breaking one for the firm and our entire team remains profoundly grateful for your support.

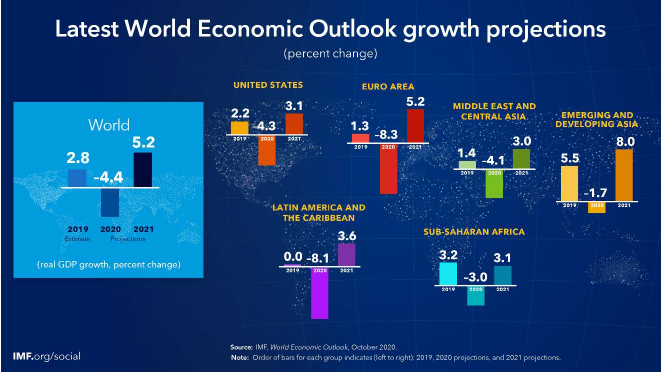

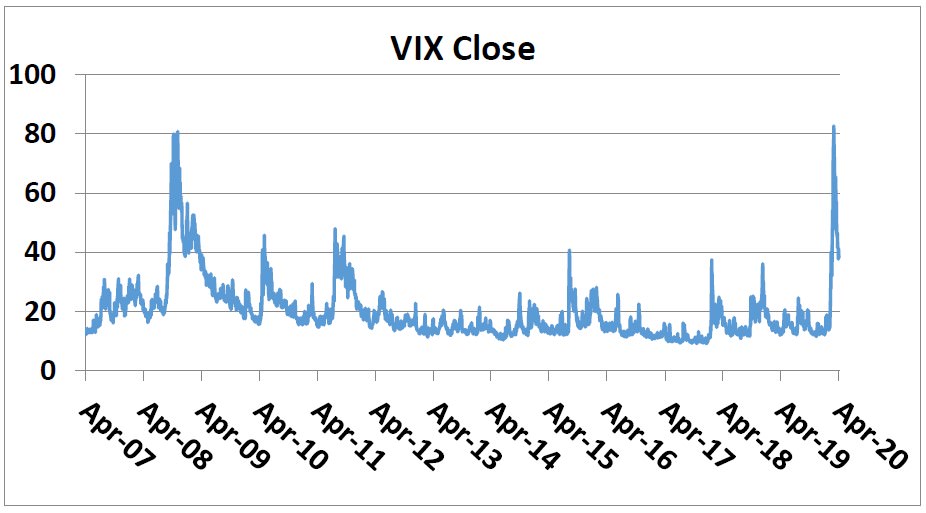

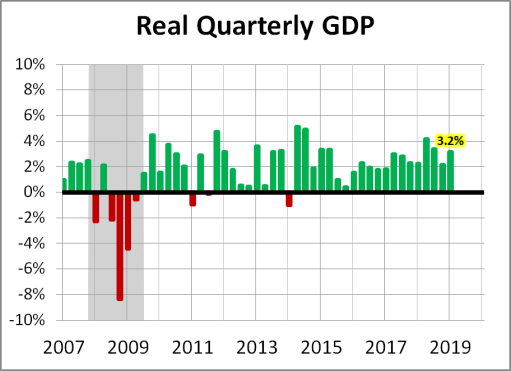

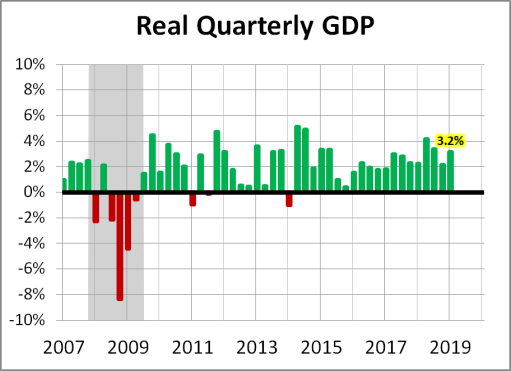

With introductory pleasantries aside and 2021 behind us, our attention turns to 2022 and what it might bring in terms of the economy, financial markets, and multifamily investment opportunities. In short, I believe this year will be challenging, with lingering uncertainties surrounding COVID (I, like many others, am recently recovered from a breakthrough case, despite my three jabs), higher interest rates and inflation, moderating economic growth, geopolitical question marks (e.g., China, Russia), and the midterm elections later this fall. I suppose one could categorize the 2022 uncertainties as either the five C’s (COVID, costs, consumers, China, and Congress), or perhaps the four C’s and two I’s (COVID, consumers, China, Congress, inflation, and interest rates).

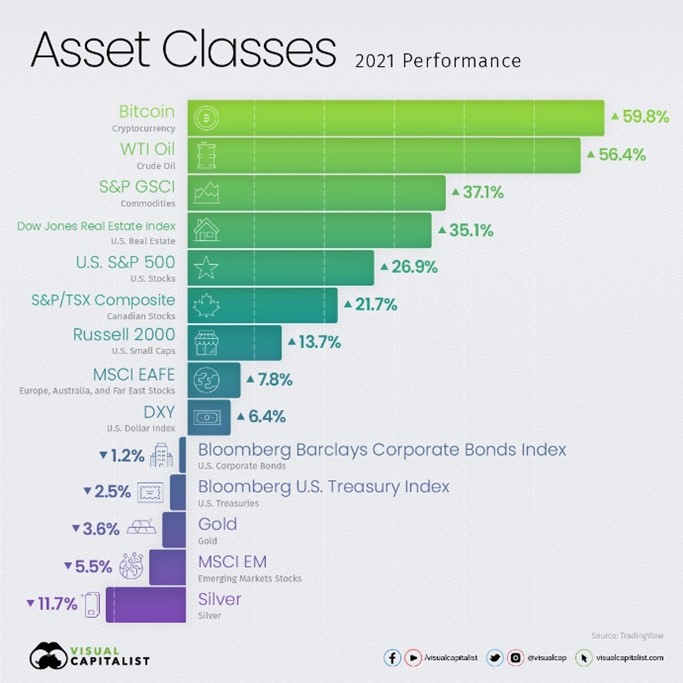

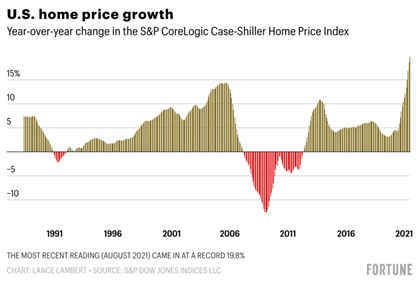

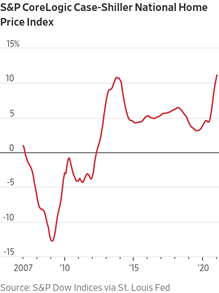

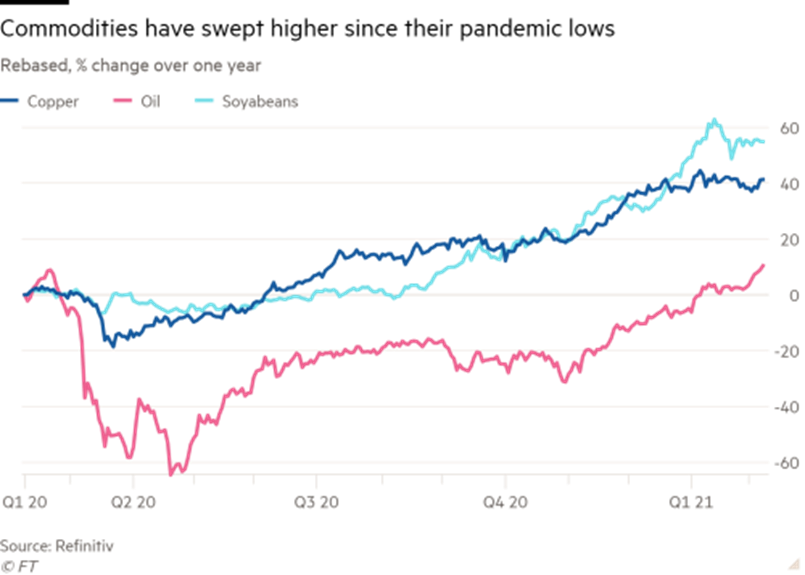

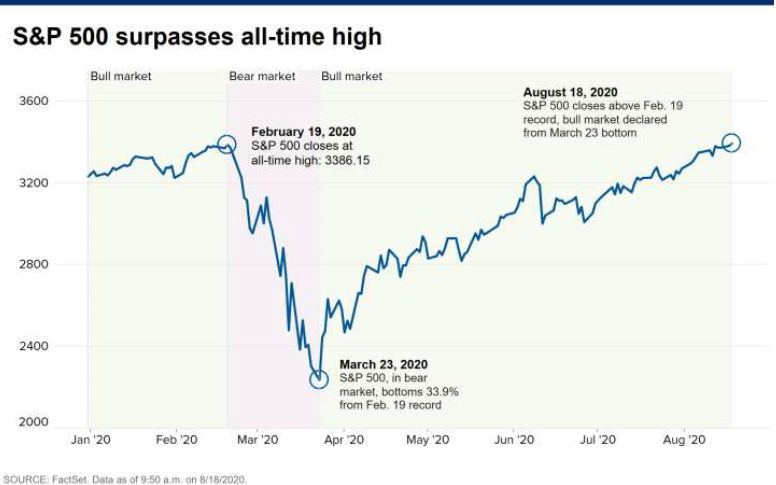

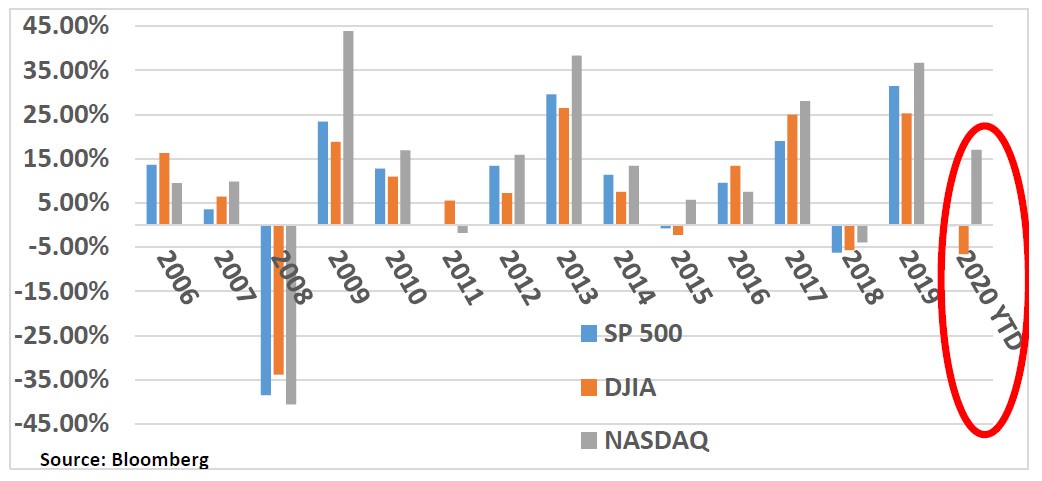

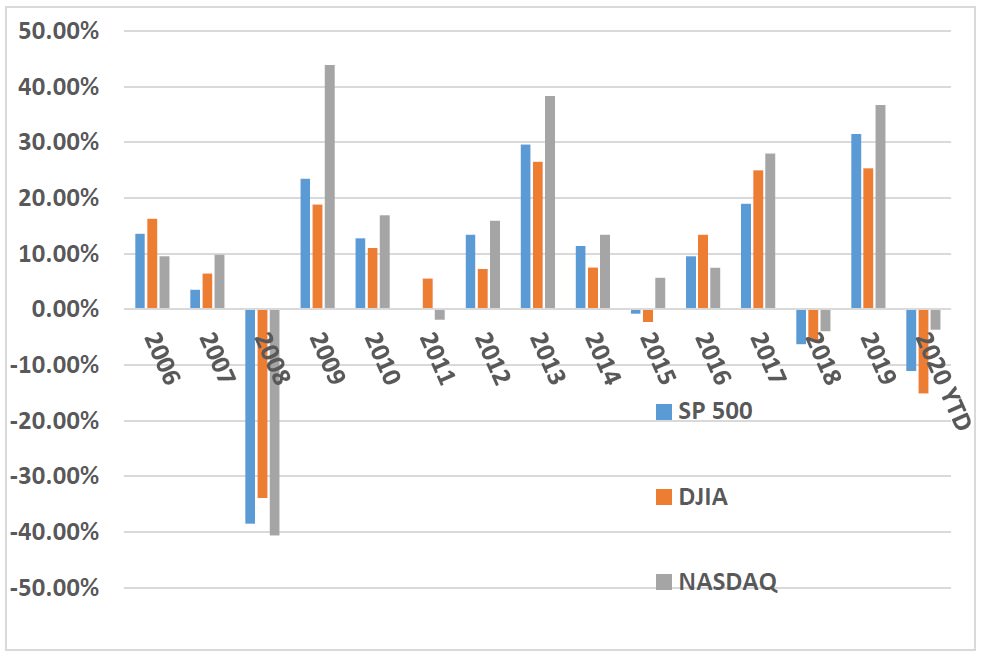

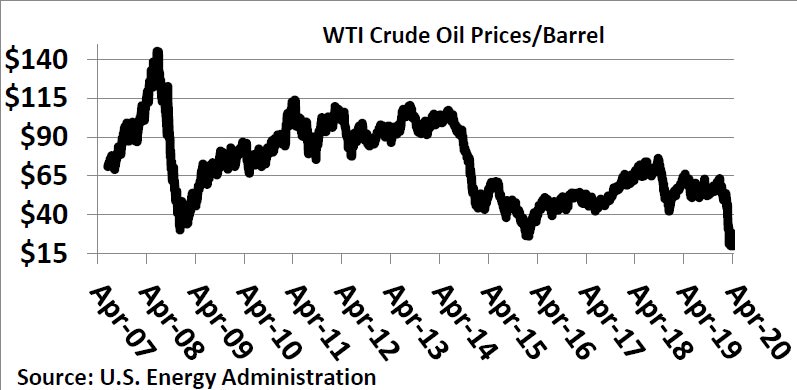

Financial markets face measurable headwinds, if just because recent performance has been so strong. Home sales volume and prices hit 15-year highs last year, up 8.5% and 16.9%, respectively. The S&P 500 was up a whopping 27%. Oil prices were up 56.4% and most other commodities (aluminum, nickel, zinc) were up more than 20%. Heck, even Bitcoin was up nearly 60%. In the face of higher interest rates, the Bloomberg Barclay’s Corporate Bond Index was only down a modest 1.2%, despite much higher 10-year Treasury yields.

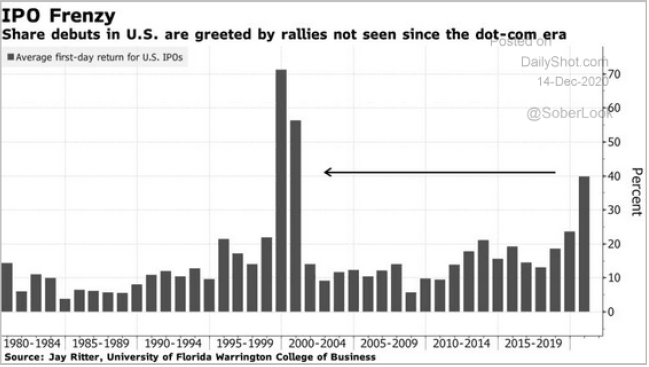

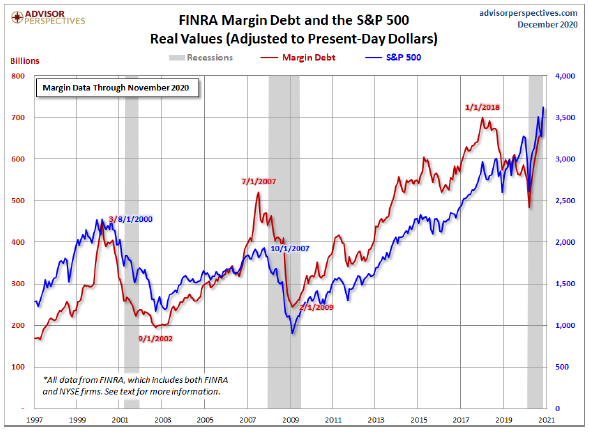

One of the other macro-level concerns is whether the air that has been recently let out of the riskier, if not, speculative asset balloon, will prove contagious. The NASDAQ has already “corrected” nearly 12.0% this year. The ARK Innovation Fund (ARKK), which holds a basket of what I would consider the riskiest of the riskiest equities, and Bitcoin are both down about 25%. SPACs (Special Purpose Acquisition Companies) as a group are down over 15% year to date. Netflix, Peloton, Robinhood, and fill-in-the-blank with your favorite highflying meme stock, are trading at 52-week lows, with Peloton and Robinhood trading below their initial public offering prices. One quote from Saturday’s Wall Street Journal seemed especially apropos, if not a tad scary: “SPACs seemed, briefly, like a way to earn easy money. Now, the hype is giving way to reality.”

“Easy money?” Phrases like that, along with Jim Cramer shouting “Booyah” on CNBC’s “Mad Money” (not to be confused with another CNBC favorite, “Fast Money”), as he provides a painstakingly detailed and thorough 30-second analysis on some fast-growing, gravity-defying stock, give me the heebie jeebies…whatever those are (I believe they are closely related to the “willies”).

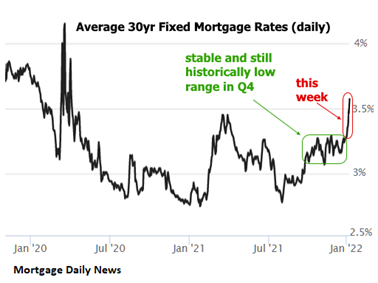

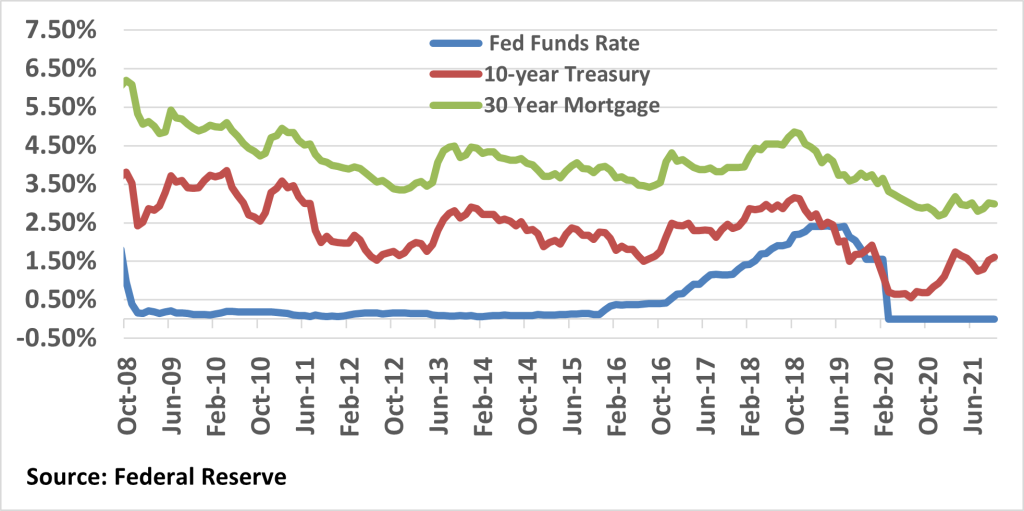

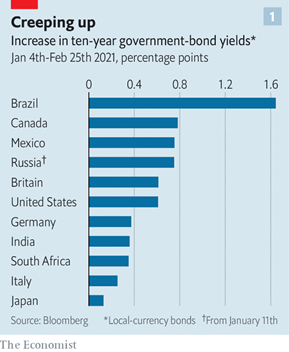

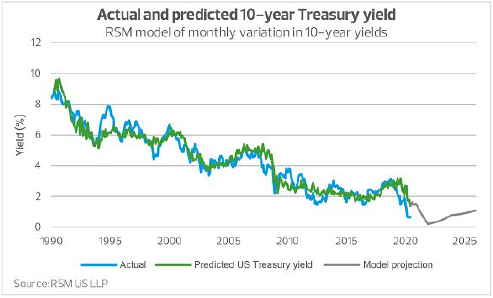

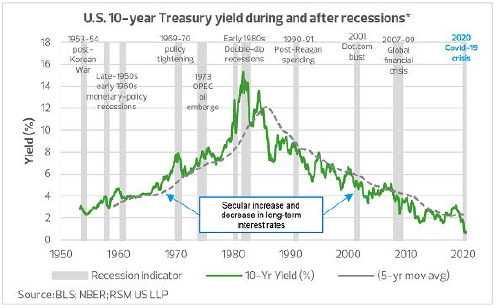

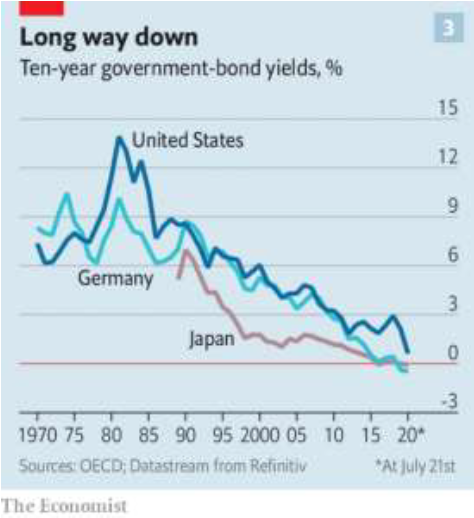

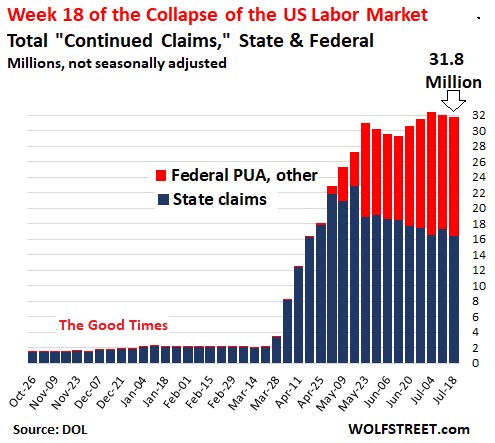

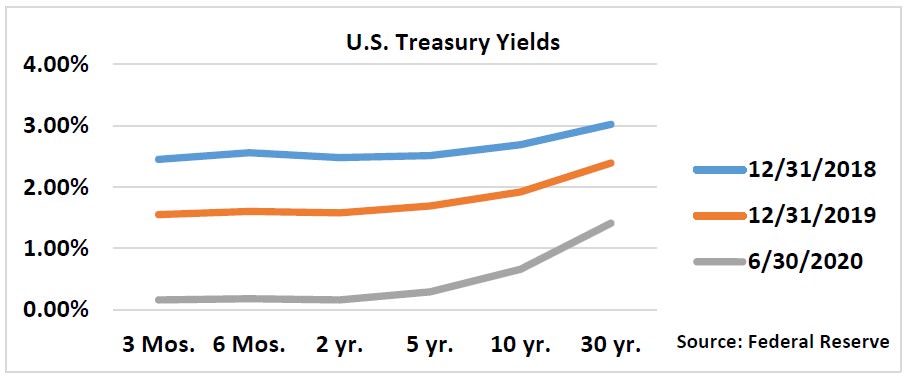

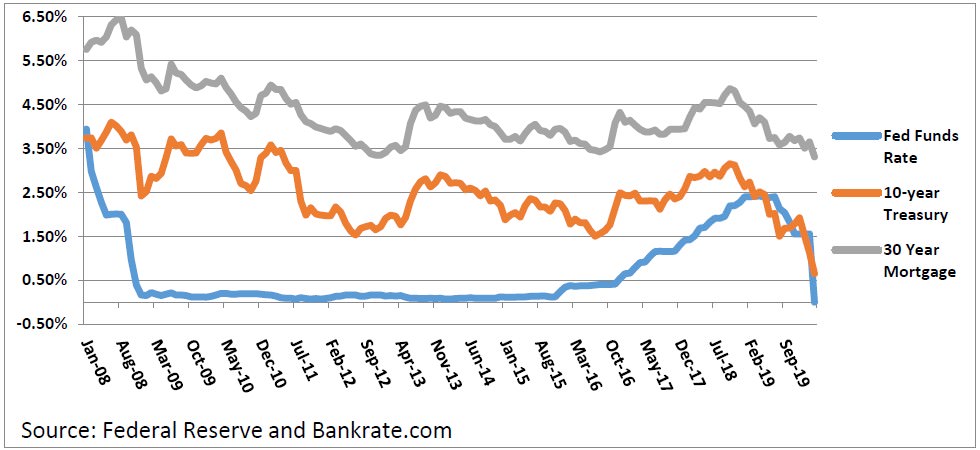

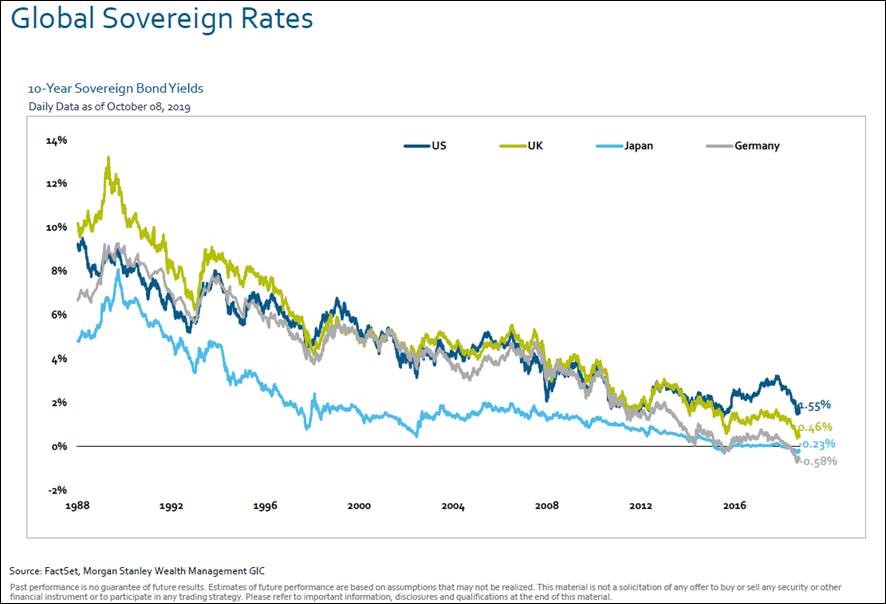

Meanwhile 10-year treasury yields have increased from 1.51% to 1.75% and 30-year mortgage rates from around 3.1%, to 3.5%. All in about three weeks. The financial market captain has illuminated the “Fasten Seat Belt” sign, and suggests you stay seated for the remainder of the flight.

That is not to say that the increased volatility and uncertainty will not present investment opportunities, a perspective Sir Churchill would endorse (see quote above), as they always do. But I am not so naïve as not to recognize and appreciate certain realities. That is, in part, what is required of us, as fiduciaries and stewards of capital. However, so much about this coming year depends on how markets respond to the Fed’s less accommodative monetary policies and whether Omicron marks the end of the pandemic or just another Greek letter in the worst fraternity ever.

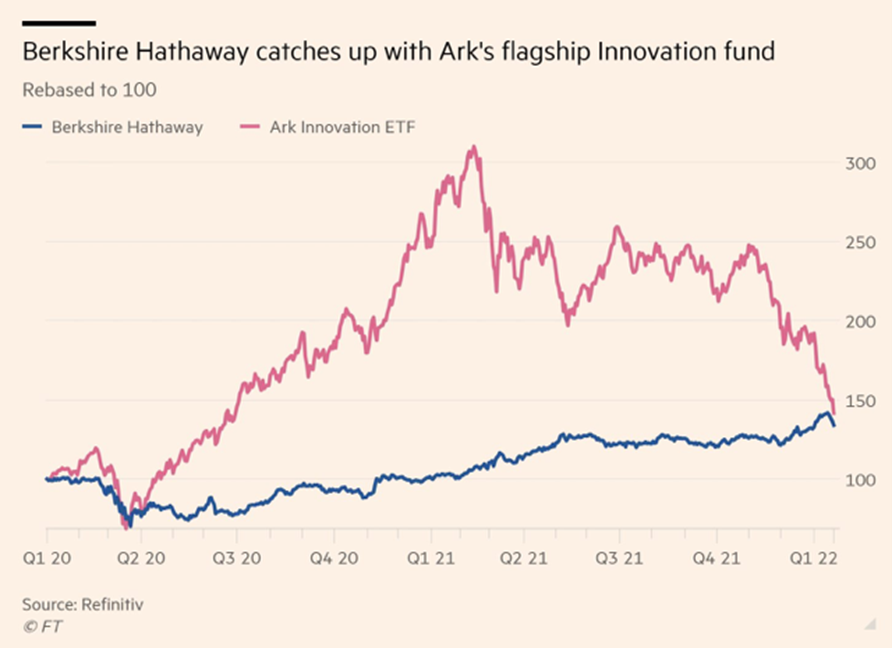

Over the last decade, growth-related investments have significantly outperformed value-oriented ones, but I sense the tide may finally be turning. According to Morningstar, value-based funds outperformed growth funds in 2021 for the first time since 2016, and it has been a rough decade for value-oriented investors. Businesses with more predictable and stable cash flows ought to be relative outperformers in markets such as these, and over time, you know, the kind of investments where making money isn’t “easy” or a “Booyah” doesn’t quite capture the fundamental analysis required to assess an opportunity. Perhaps this simple picture comparing recent relative performance of Berkshire Hathaway to ARKK is telling. Value investing may finally be having its day…or year…or…

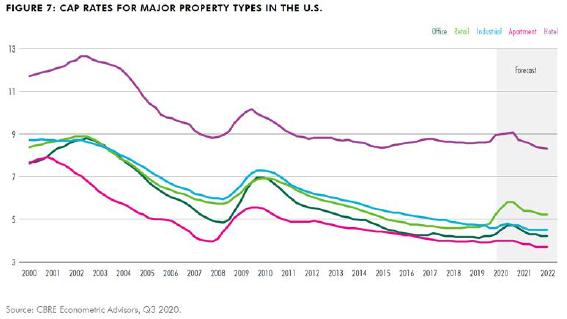

While I know this will shock nary a single reader as I have a habit of beating the same proverbial drum, but I would include multifamily residential properties in the mix of stable, cash-flow producing assets that ought to perform relatively well in these volatile markets. While I don’t anticipate multifamily or other commercial real estate prices (i.e., industrial warehouses) to repeat the stellar performances they have experienced in recent years, assets with reasonably stable and predictable cash flows, combined with modest leverage, should be a valuable combination in markets such as these. Regardless, careful underwriting, asset selection, and market analysis will be especially important.

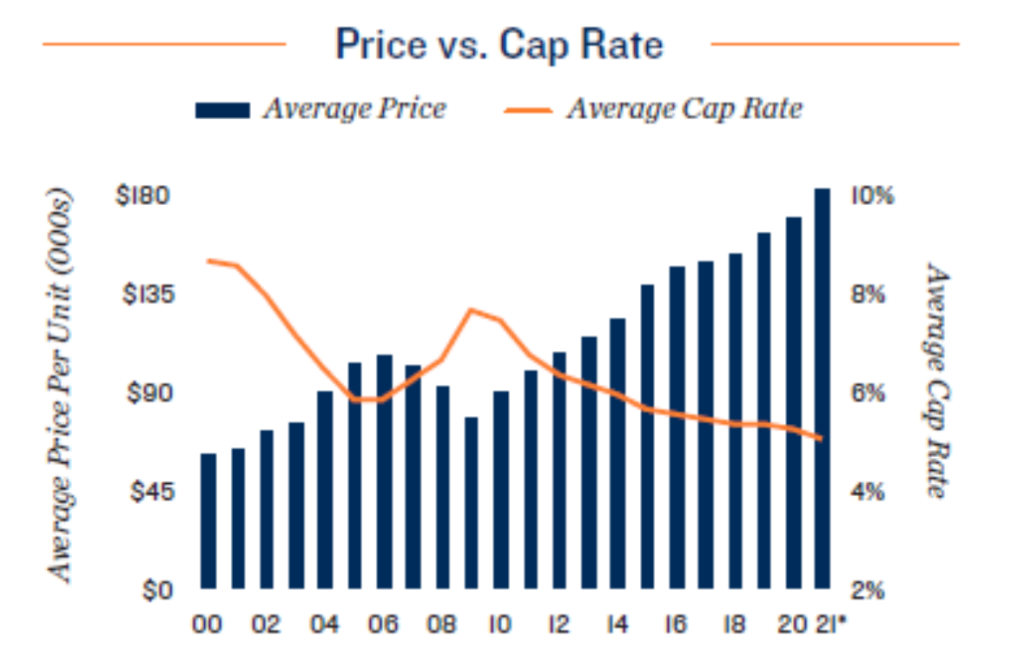

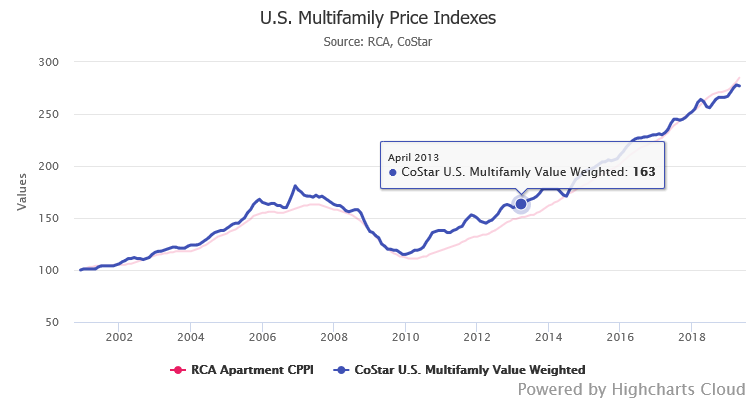

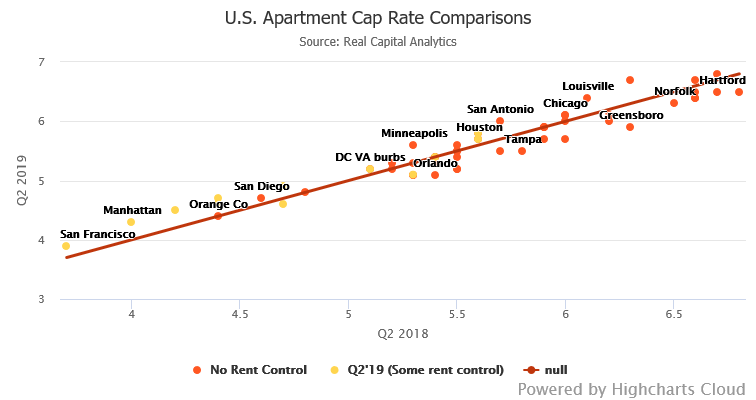

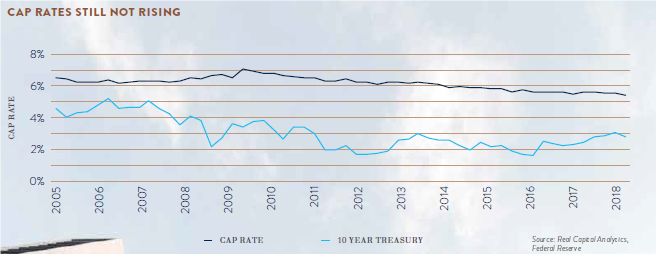

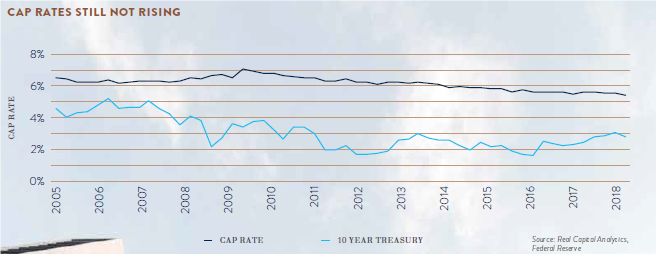

While this final picture paints quite a compelling picture and describes what has happened with multifamily pricing and cap rates over the last decade plus, I don’t anticipate the slope of either average prices paid per apartment unit or average cap rates to continue so linearly looking forward. It may not be that returns always revert to their long-term averages, but rather that trees don’t grow to the sky (and the corollary, roots don’t grow to the center of the earth).

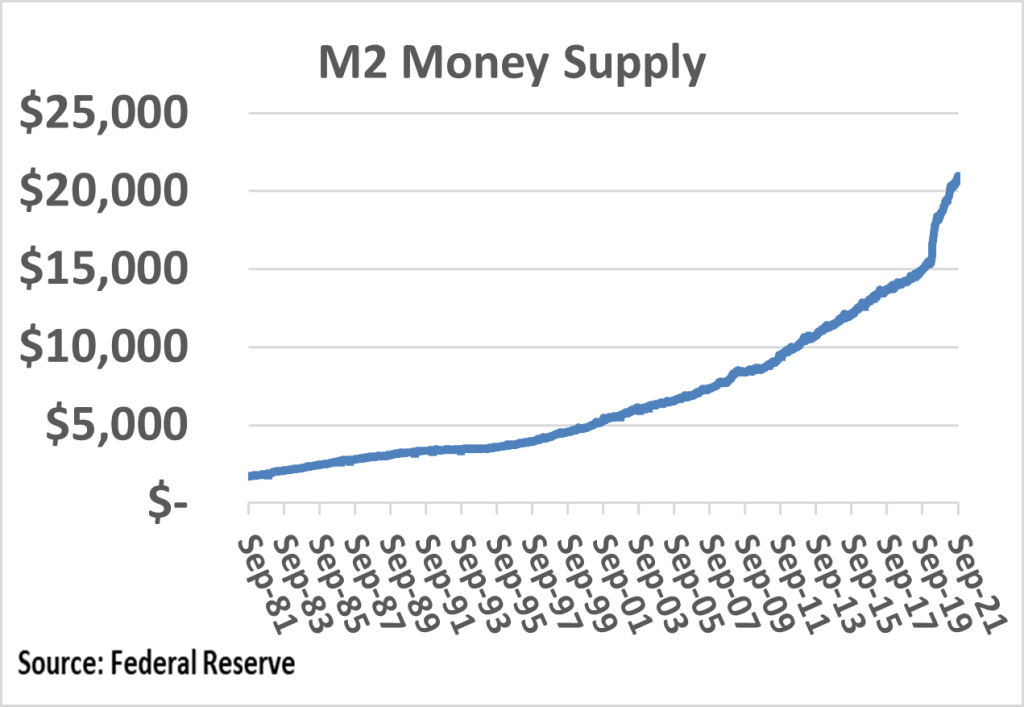

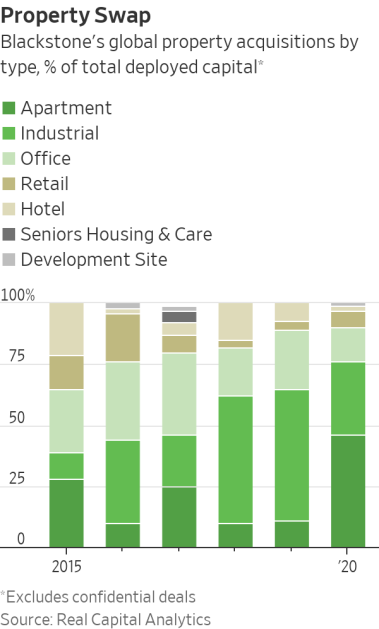

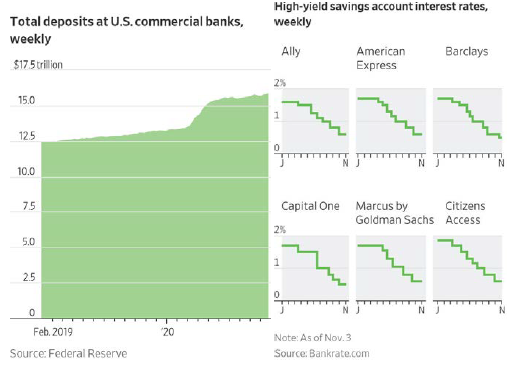

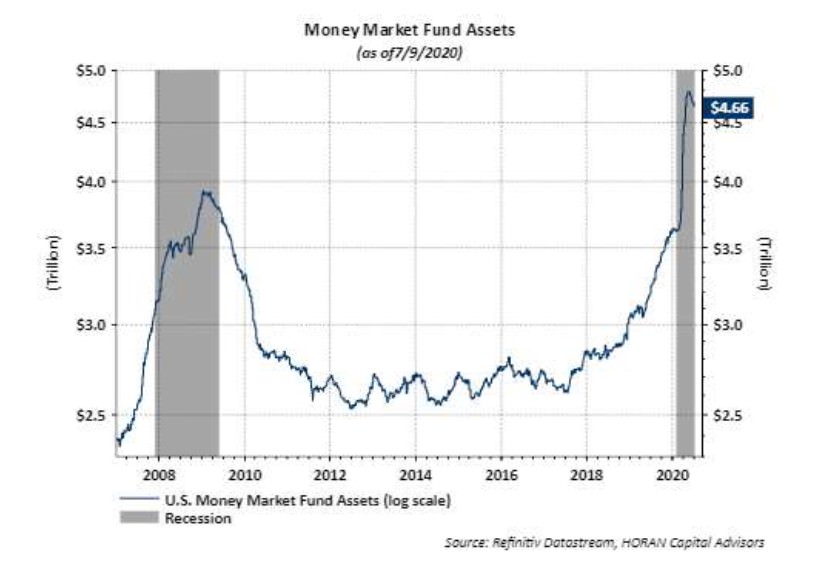

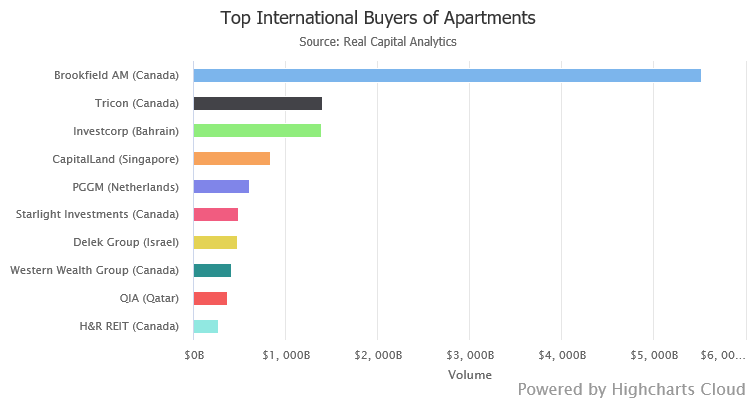

However, if one remarkable tailwind remains, it is all the dry powder out there. The Blackstone Property Fund, a non-traded Real Estate Investment Trust, surpassed $50 billion in assets last month and has been raising $2 billion per month from retail investors since the middle of 2020. $2 billion a month! Not sure that kind of inflow qualifies as “easy money,” but it is certainly a lot of capital to deploy. Meantime, M2 money supply (cash, checking and savings accounts, money market funds, time deposits), all earning negative real returns (after inflation), approximated $21.5 trillion at the end of 2021, another all-time high, and a decent chunk of those funds will likely end up being invested in riskier assets at some point. The only question is when and where these assets go.

In conclusion, I could really use a Ouija Board and some tea leaves to forecast 2022 with so much depending on what is challenging to predict or know: the pandemic and what happens post-Omicron, politics, the impact of changing Fed policy, inflation, interest and mortgage rates, and the employment picture. As an information junkie, it should be a very interesting year, and I will do my best to try and make sense of it all and hope you will stay tuned alongside me and the rest of the Clear Capital team as we endeavor to do so.

While the fundamentals for multifamily residential assets remain strong, we cannot ignore the impact that higher interest rates, slower economic growth, challenging collections, protective tenant policies, the changing employment market, and other uncertainties may have on rents and values

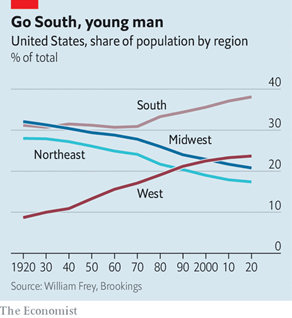

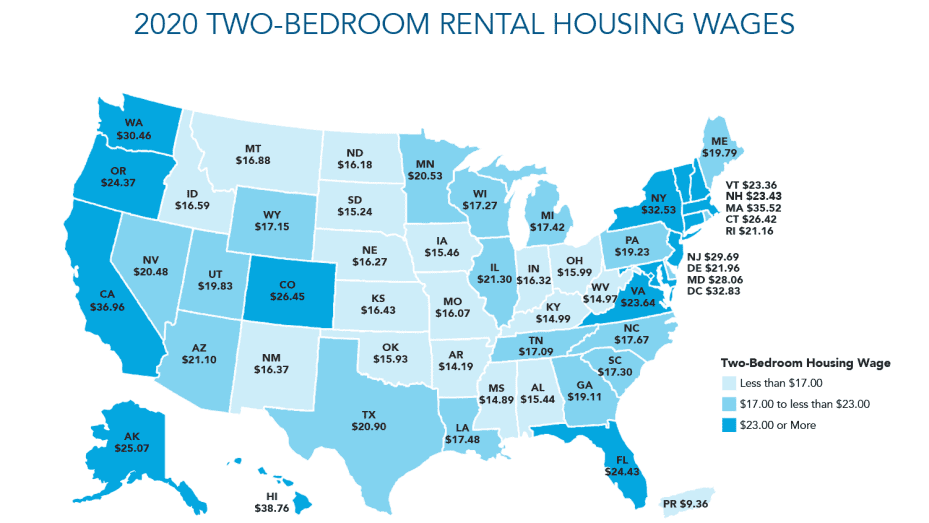

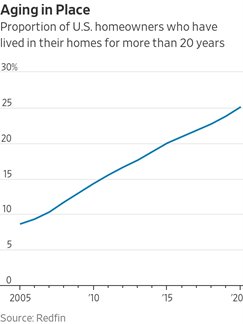

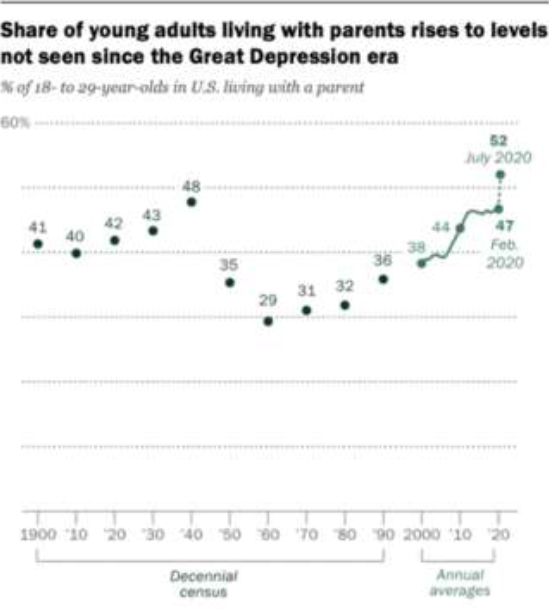

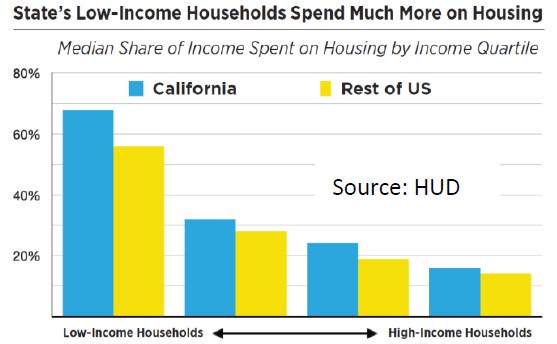

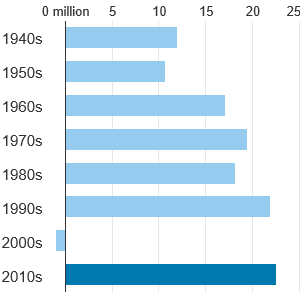

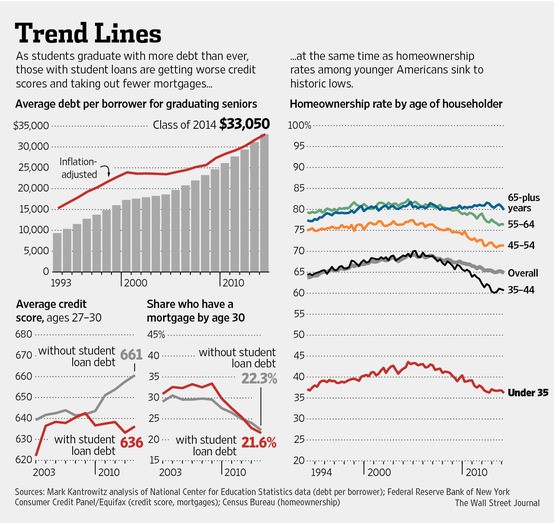

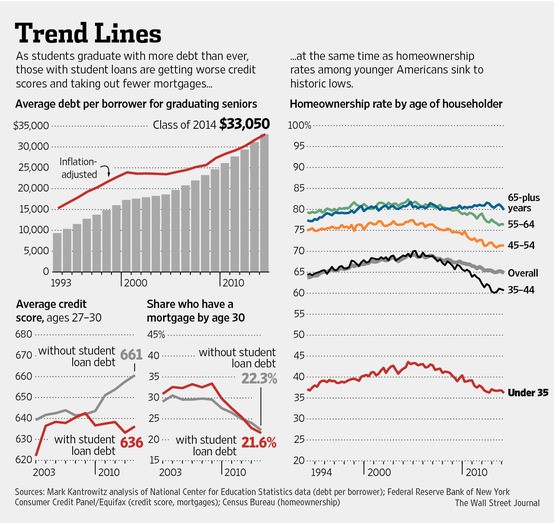

As alluded to above, I am often (and very appropriately) accused of repeating the same theme and beating the same drum every quarter, the “Gospel of Multifamily Investing.”™ I won’t plead the Fifth, but willingly admit guilt. For the last 20 years and more, I have preached that the future of housing in the U.S. is higher-density, multifamily housing, and that housing affordability would lead to increased relative demand for apartments, domestic migration (Manifest Destiny, in reverse, so to speak, as elaborated upon below), and multiple generations living under a single roof. These trends have come to pass, and I cannot see any reason as to why these macro-level realities will change any time soon, if ever.

However, to simply purchase assets indiscriminately, ignoring cycles, macroeconomic data, and geographic particulars (distinctions between various markets and submarkets), is not something we are ever going to do. The key is to recognize, appreciate, and evaluate the data, exercising even greater care and attention to detail while underwriting any potential investment opportunity. Obviously, we are not always right, but I believe our long-term track record speaks for itself.

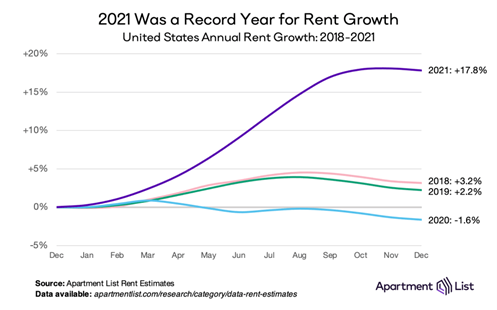

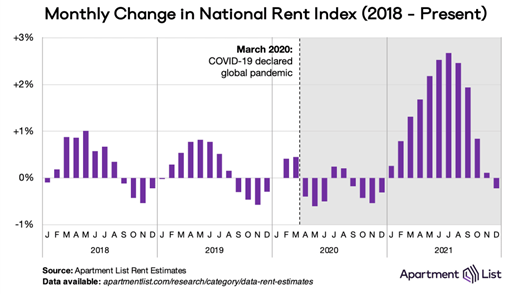

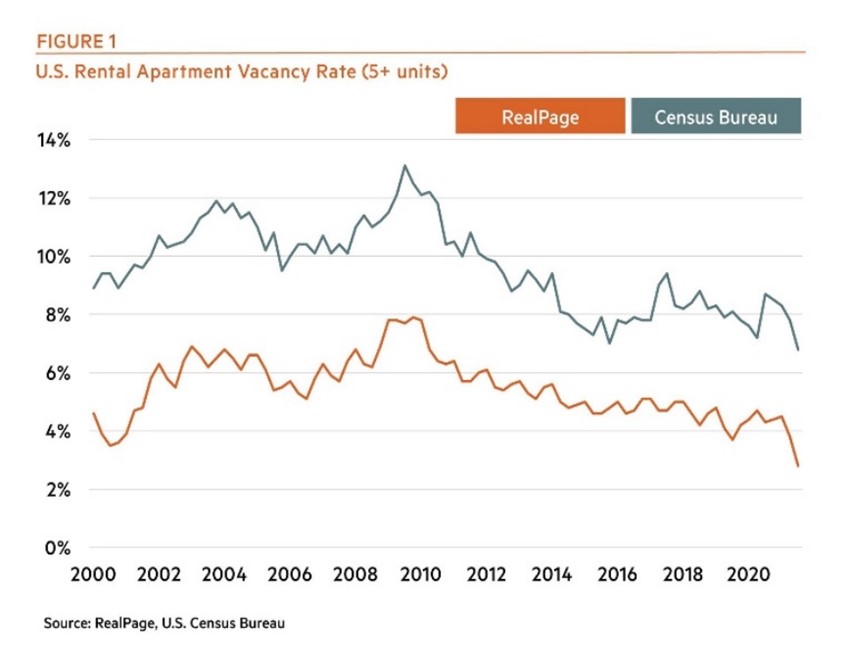

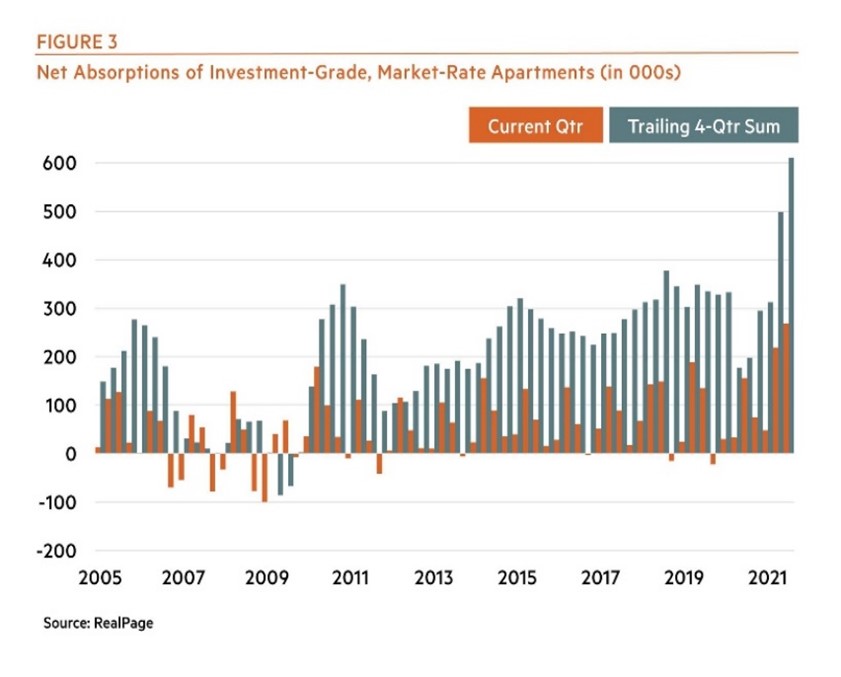

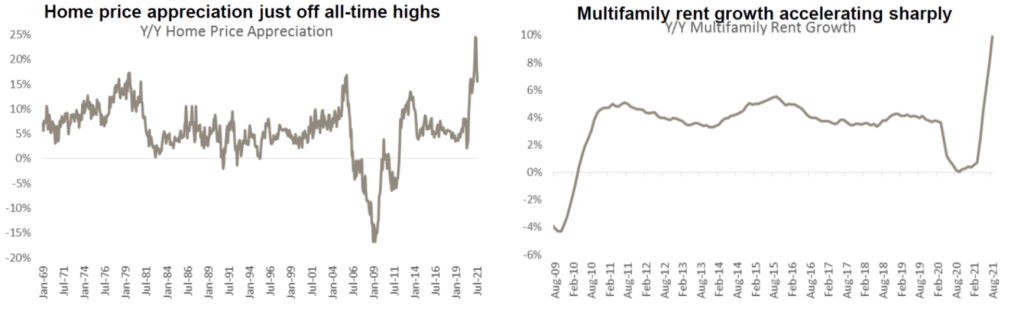

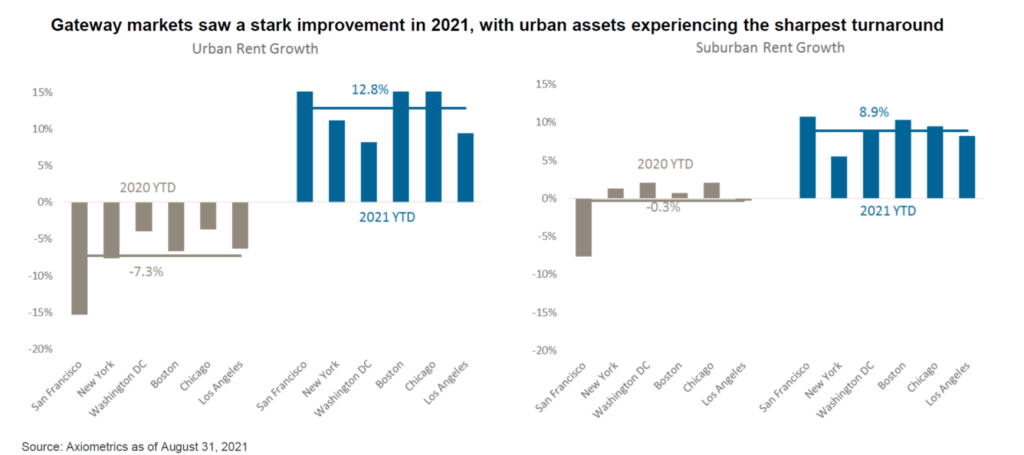

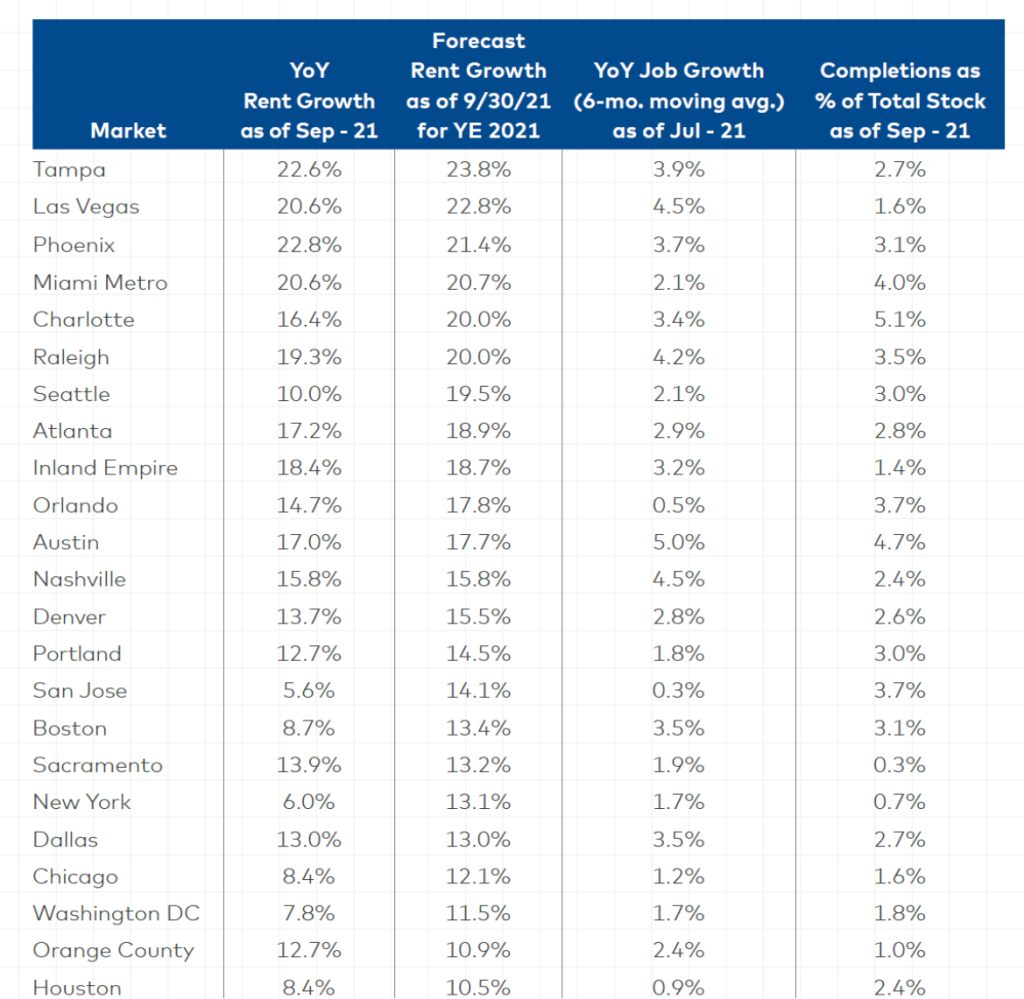

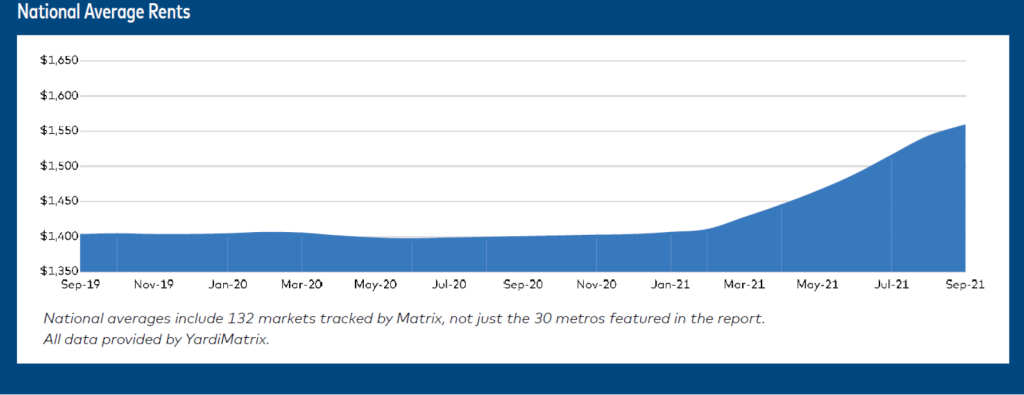

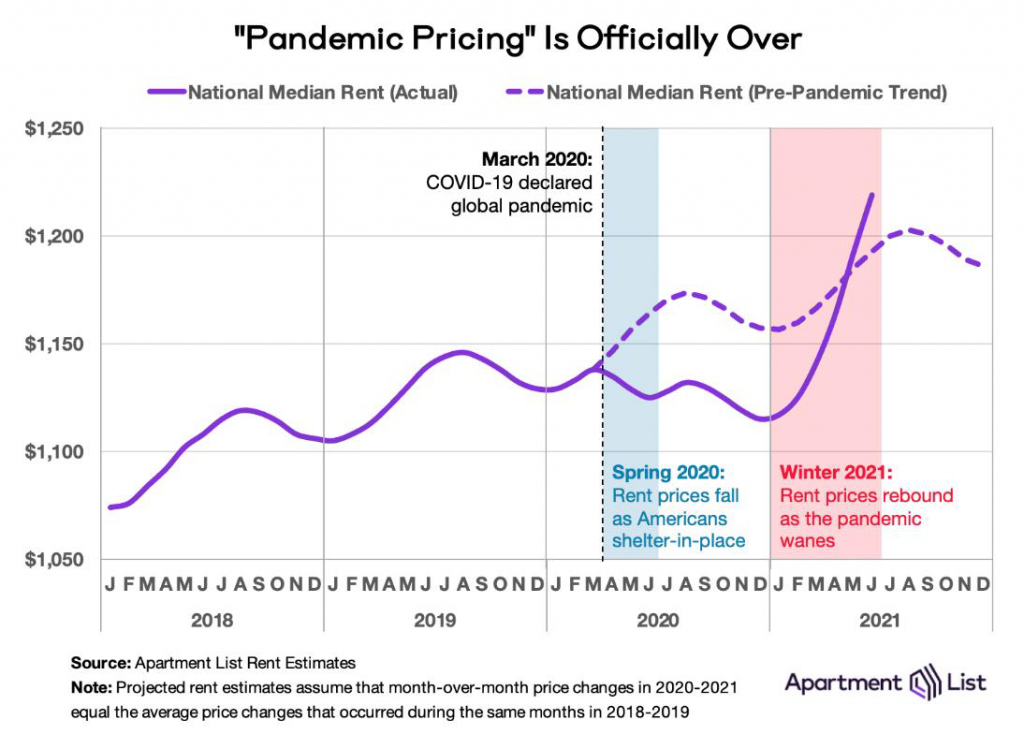

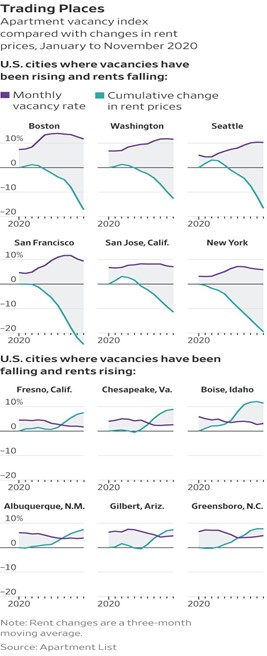

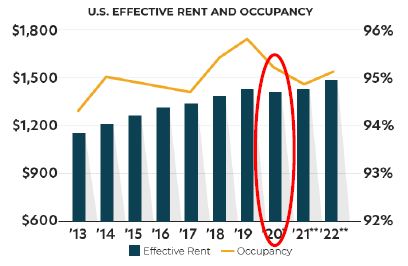

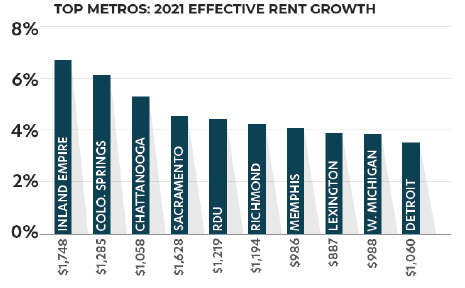

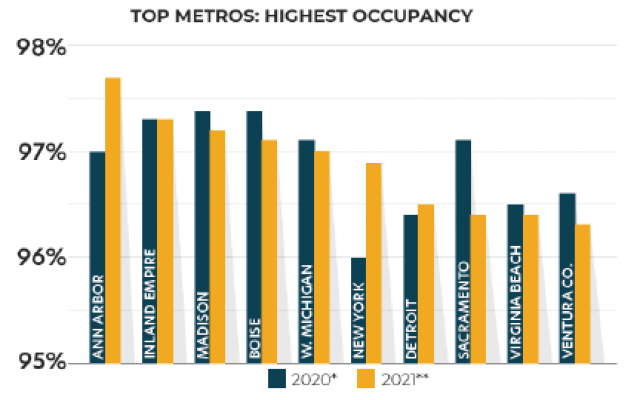

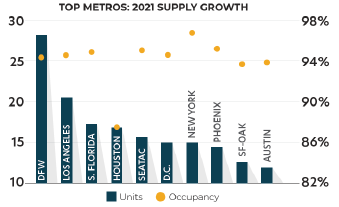

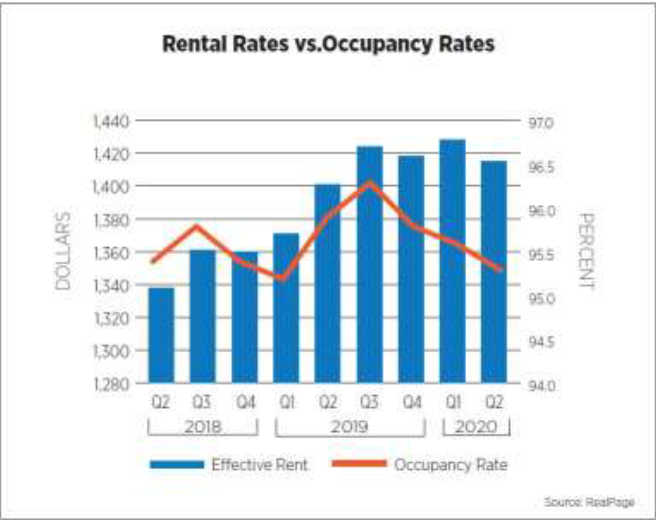

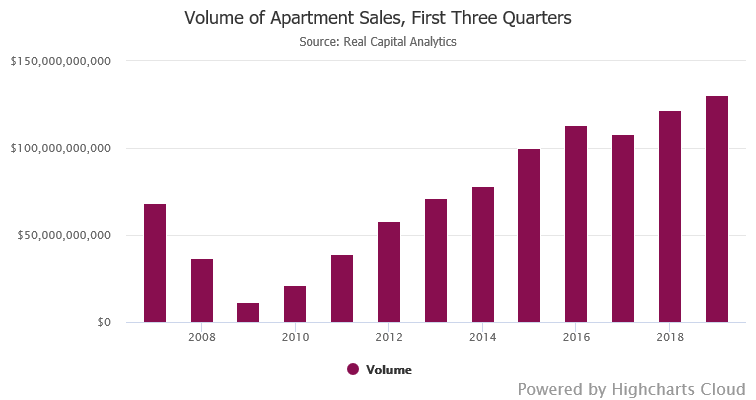

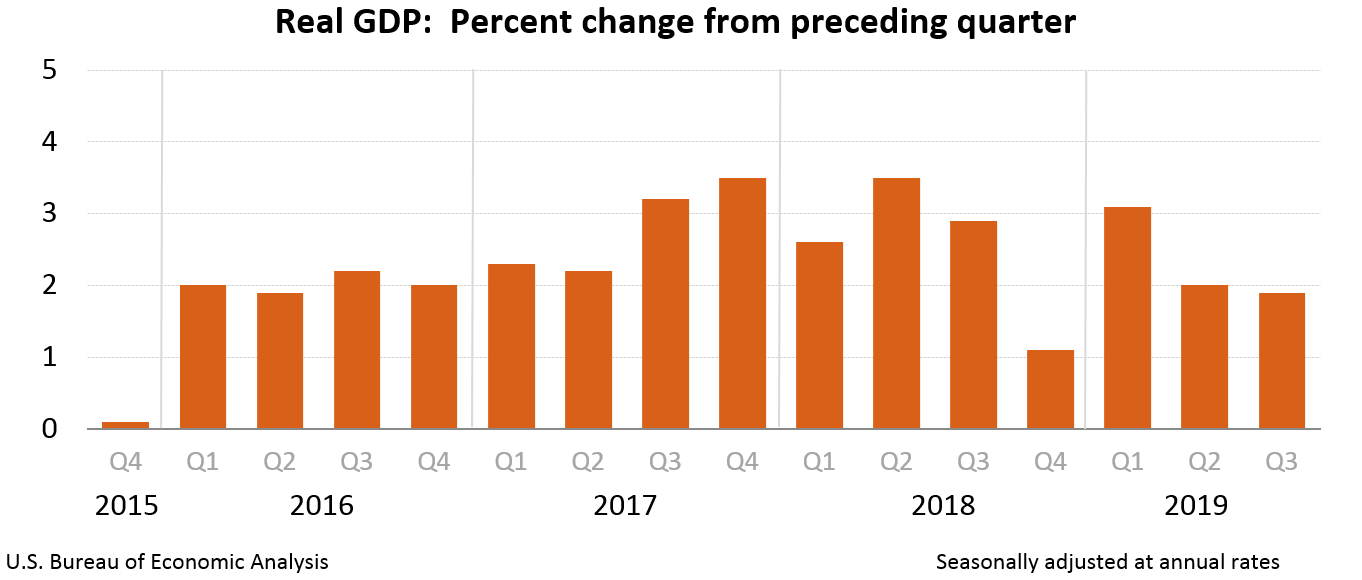

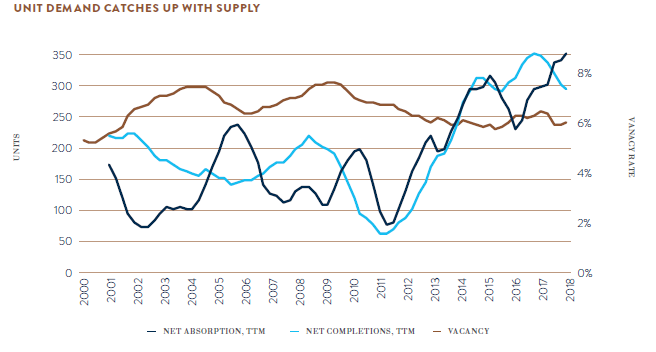

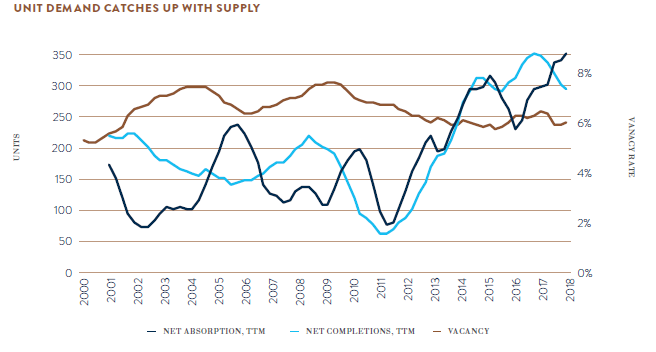

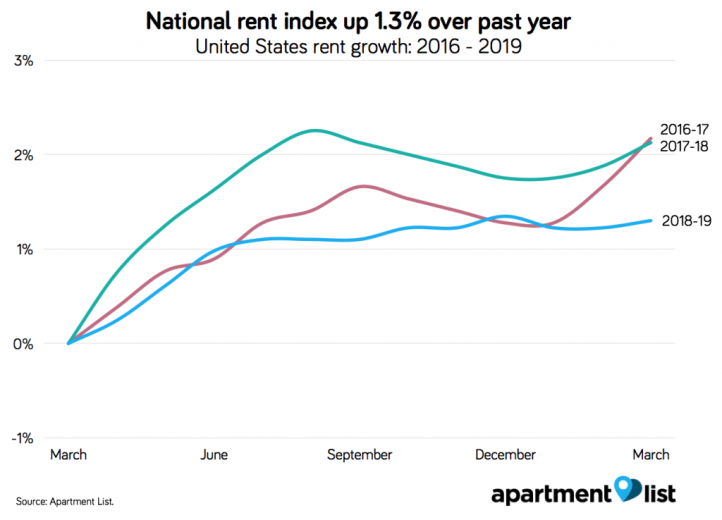

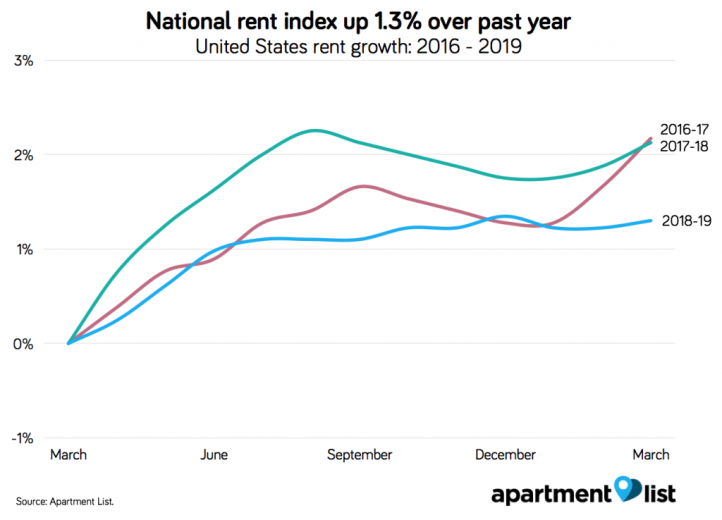

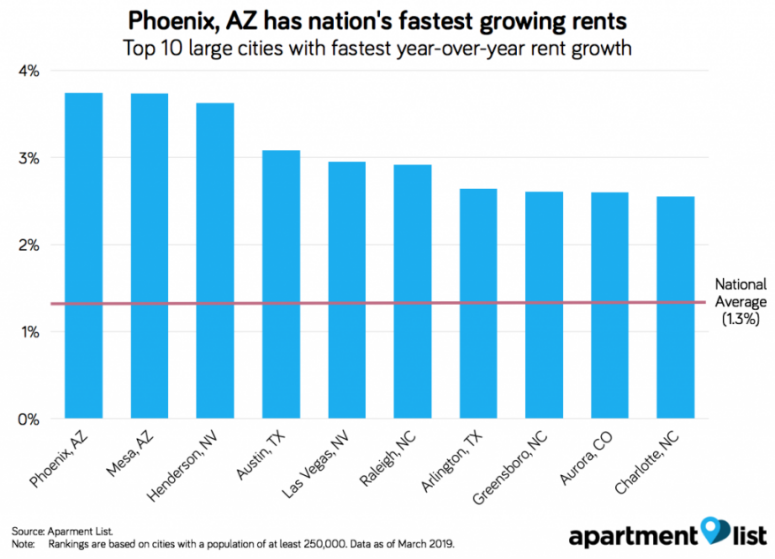

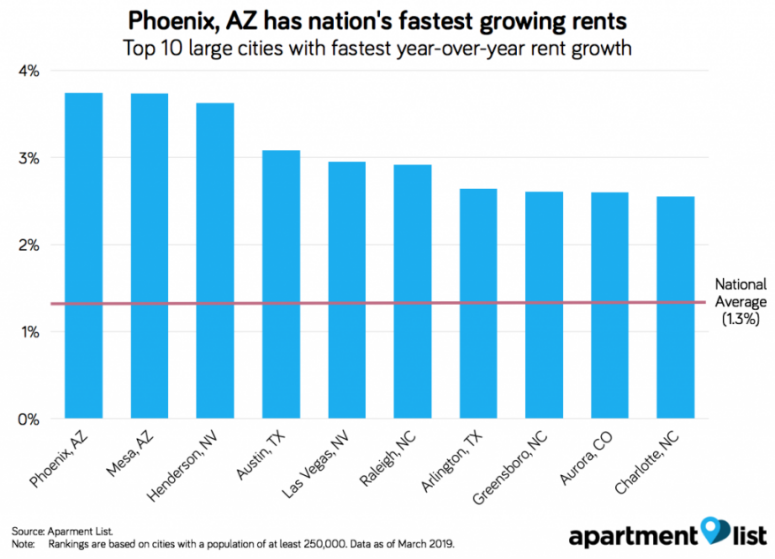

Let’s start with some data from 2021 and the first part of 2022, which essentially tell the broad multifamily story. Rents and net absorption of units (net units rented) increased sharply during the year. Vacancies declined. In all markets. While the first graph is certainly eye-popping, the second may be more telling. Rents increased in every month of 2021 except December, when they declined ever so slightly. But the trend between the end of summer and year-end was telling, as rental growth moderated substantially during the latter half of the year. That is no surprise and was bound to happen, but is probative when thinking about 2022, when I expect rental growth to return to more normal levels, like those experienced prior to the pandemic.

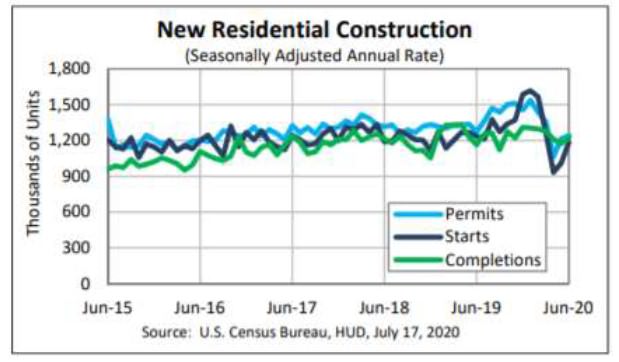

To witness this sort of rental growth and a decline in the overall vacancy rate is quite remarkable, reflecting the economic and employment recovery, sharply higher single-family home prices, and moderating construction starts and units brought to market due to supply chain disruptions and a shortage of construction workers.

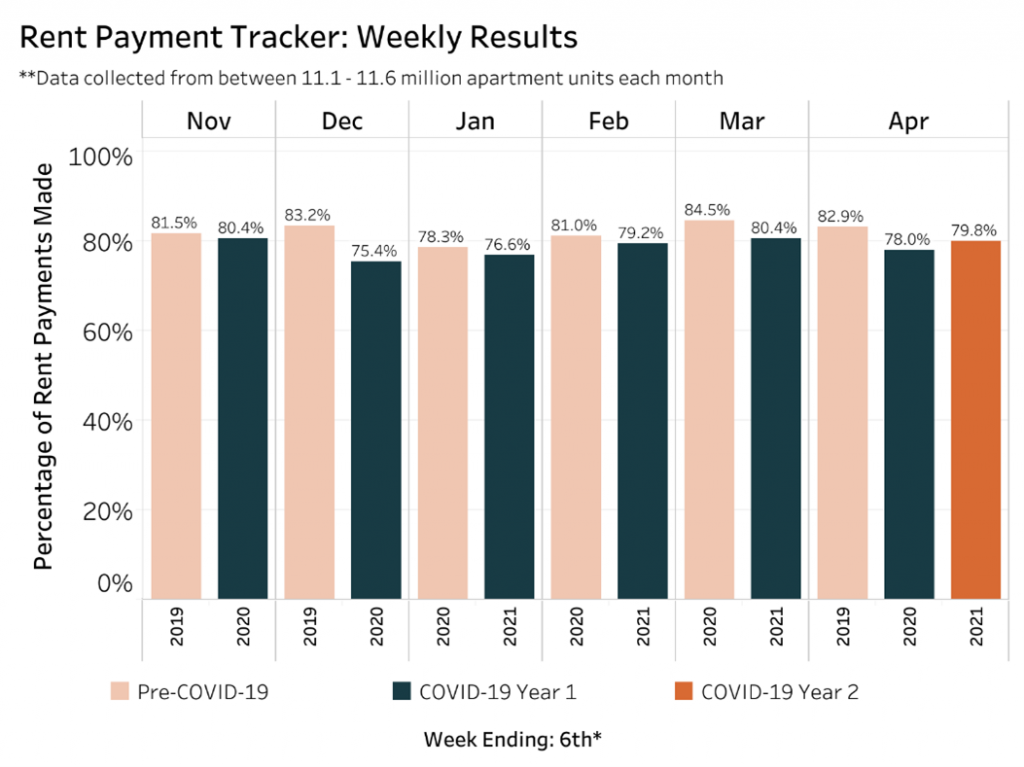

But it isn’t all peaches and cream, and higher rents, occupancies, and unit absorption can be deceiving, because all neglect to capture whether landlords are actually collecting the higher rents or whether tenants are moving and relocating as one would expect in a “normal” market. This is where the impact of the pandemic is clearly seen and skews the data. Collecting scheduled rents and evicting delinquent tenants remain challenges, even as eviction moratoriums burn off. In most jurisdictions, the courts are unable to process the backlog of unlawful detainer actions.

So, it is this sort of MMA battle between competing forces, as I so often describe. Demand is trickier to forecast because it depends on so many unknowns: changes in GDP and employment (which in turn are driven by everything from COVID to the future of remote work), the equity markets, interest rates, consumer sentiment, and household formation. There is no question that higher interest rates and elevated single-family home prices will increase demand for apartment units, all else equal. Otherwise, more precise demand forecasts are challenging.

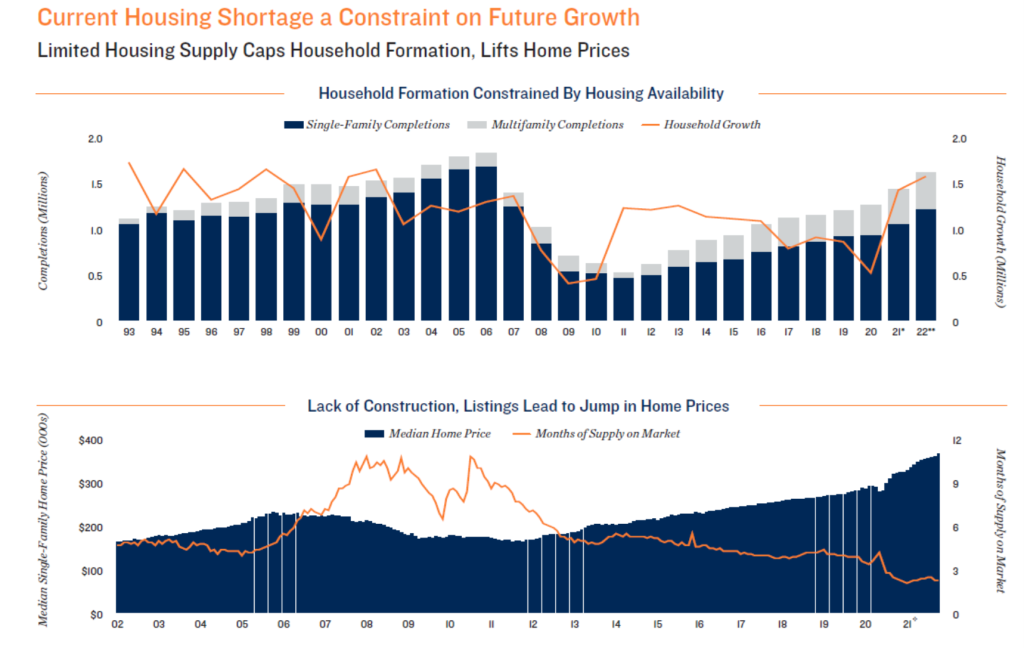

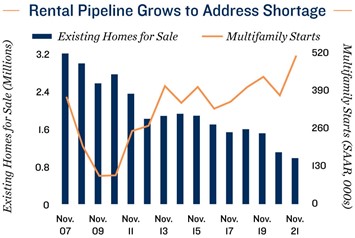

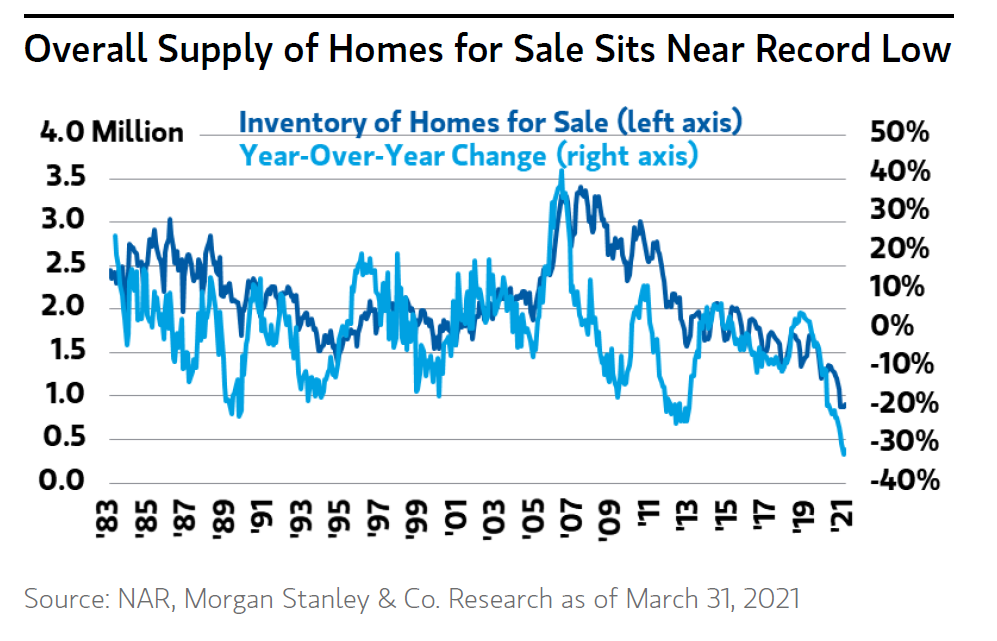

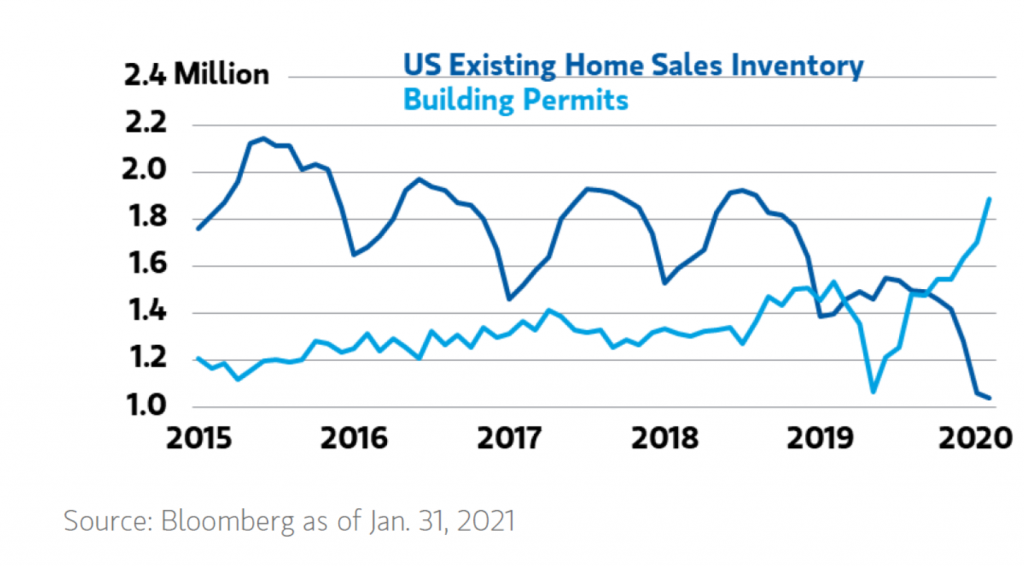

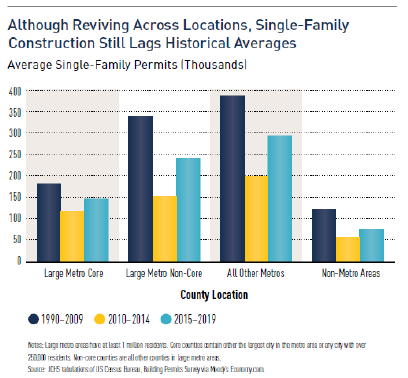

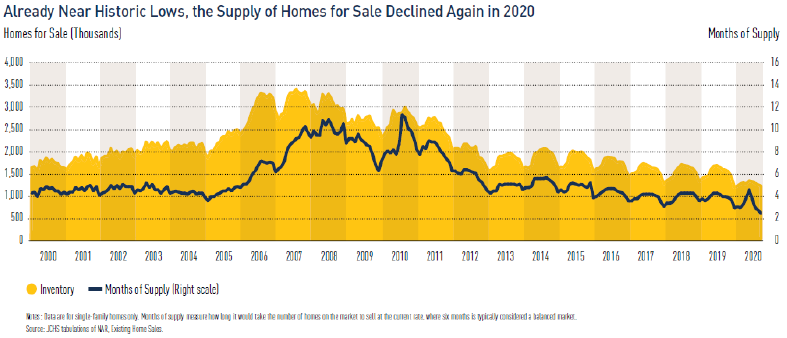

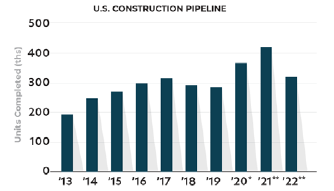

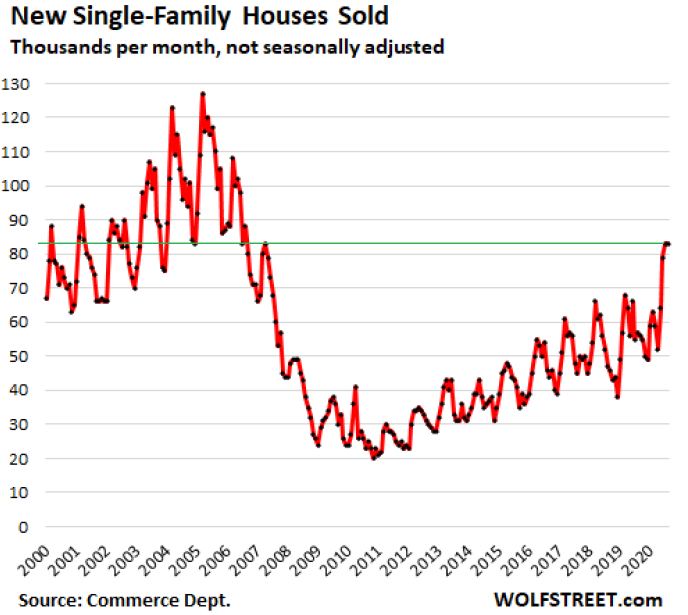

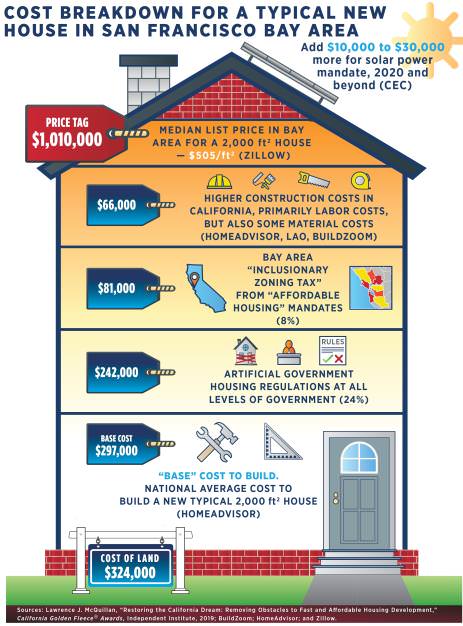

Supply is a bit easier to forecast, if just because the amount of land available for development is essentially fixed and new housing units in the pipeline, whether single- or multifamily, can be quantified, at least to some degree. From my perspective, this has been and will continue to be the housing rub. We cannot construct enough units to catch up and keep up, and I cannot foresee that changing anytime soon, even with recent increases in multifamily starts. Besides, new units coming to market are virtually all “Class A,” focused on the higher end of the market, as opposed to workforce housing, the sort of assets that Clear Capital seeks to acquire.

In summary, multifamily fundamentals remain solid and should benefit from an improving economy, labor market, higher interest rates (reducing housing affordability), and excess liquidity on the sidelines. But rental growth nationally this year will likely be quite modest, more like what occurred before the pandemic and during the latter half of 2021, while cap rates remain flat or even expand modestly.

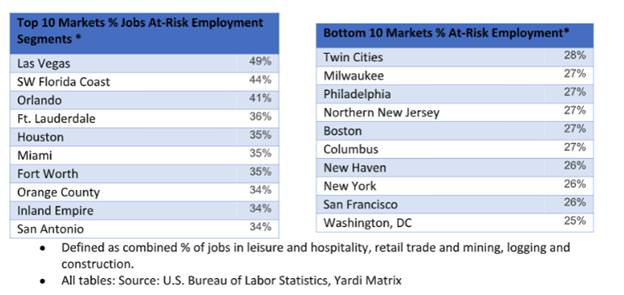

So, what housing markets look best for 2022 and beyond? Where are potential apartment renters headed?

Location, location, location. Some may believe this platitude is the real estate equivalent of “Booyah,” but I don’t think so. It may be overly trite and simplistic, but we can all agree that there is a lot of truth to it. Not surprisingly, we spend a lot of time thinking about which markets in which we want to pursue opportunities, and then, in those markets we find attractive, the specific submarkets on which to focus. Consider our projects in Colorado Springs or Lakewood, both outside of Denver, or those in Gresham, Oregon City, or Eugene, Oregon, all essentially exurbs of Portland.

As we have discussed at length in previous quarterly updates, the U.S. population, like a fidgety child on a long car ride, has never sat still. For those of you are willing to head back to high school history for a moment (don’t worry, just a moment), we may remember being taught “Manifest Destiny,” the 19th century doctrine or belief that the expansion of the U.S. throughout the American continents was inevitable and justified. Perhaps not politically correct today, but the phrase “Go West, young man,” concerning our expansion westward, relates to Manifest Destiny.

Following World War II, as automobiles and highways became omnipresent, and so westward and southbound we went. To the suburbs we moved. To warmer locales, we flocked. My father did exactly that, moving from New York City (yes, the East Bronx for those of you interested in such things), to New Orleans for medical school, and then to Southern California for the opportunities it presented (thanks, Dad), including the opportunity to meet attractive and intelligent co-eds attending UCLA (thanks, Mom).

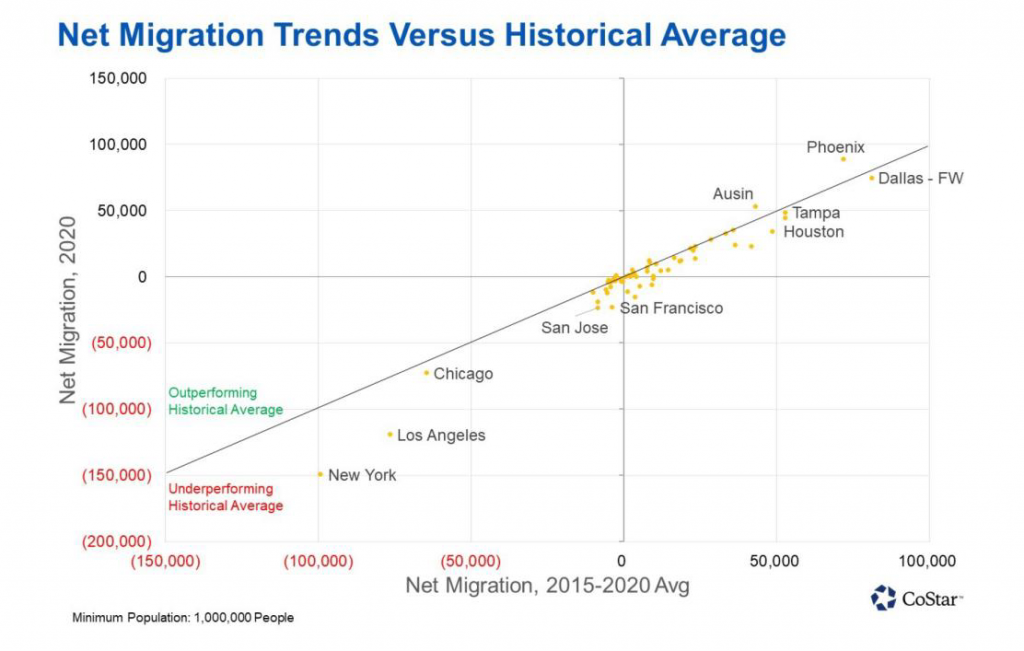

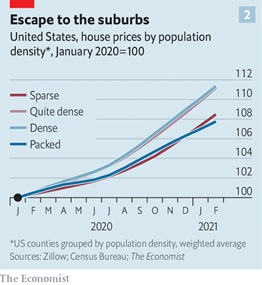

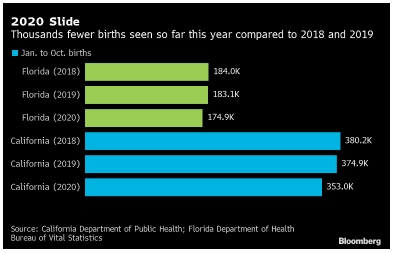

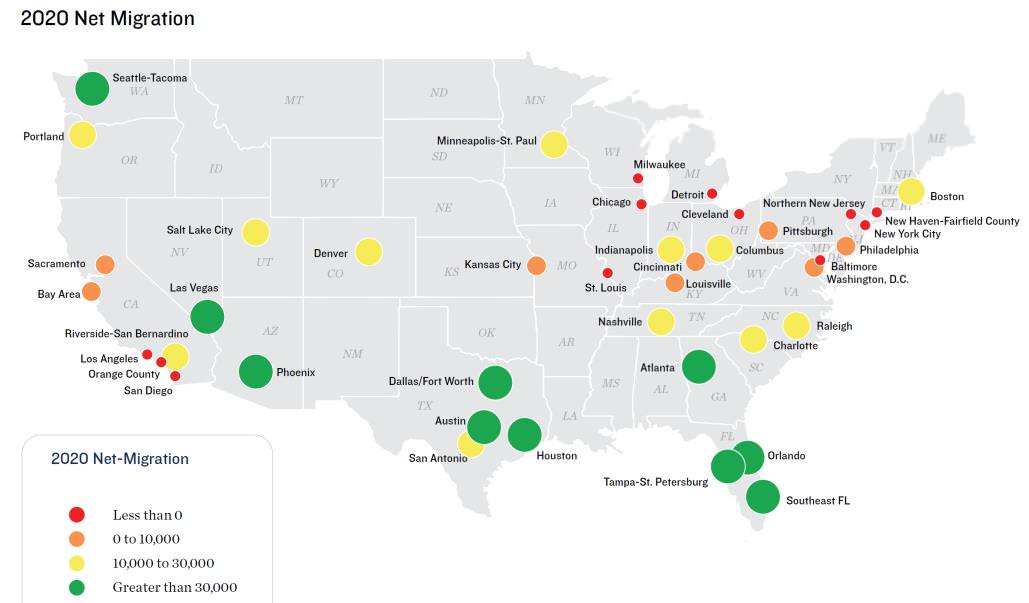

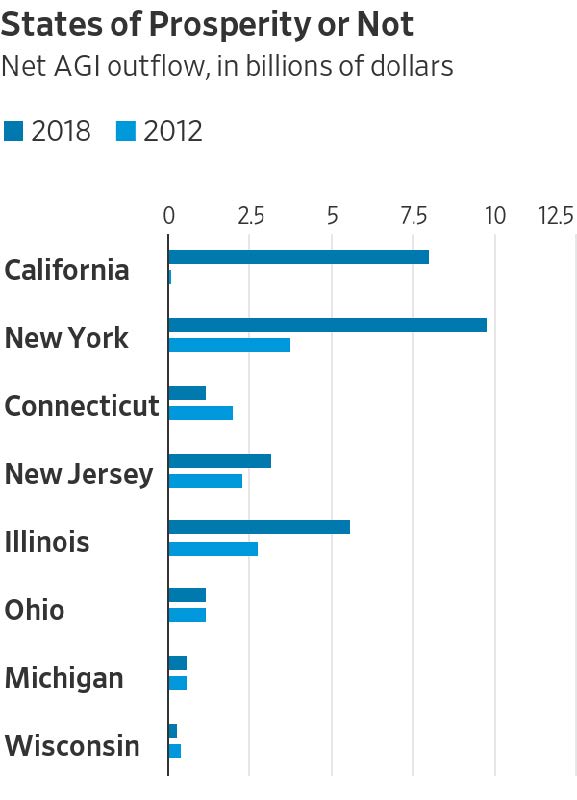

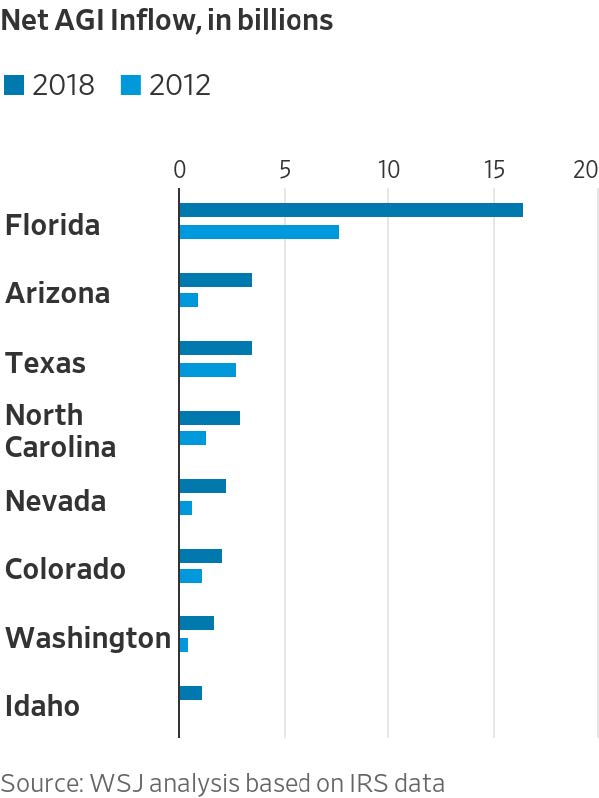

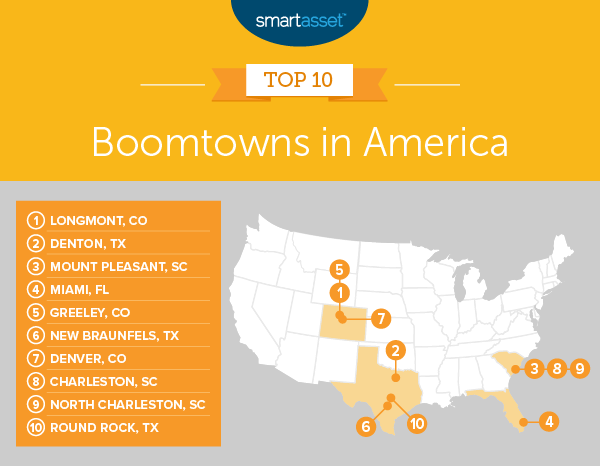

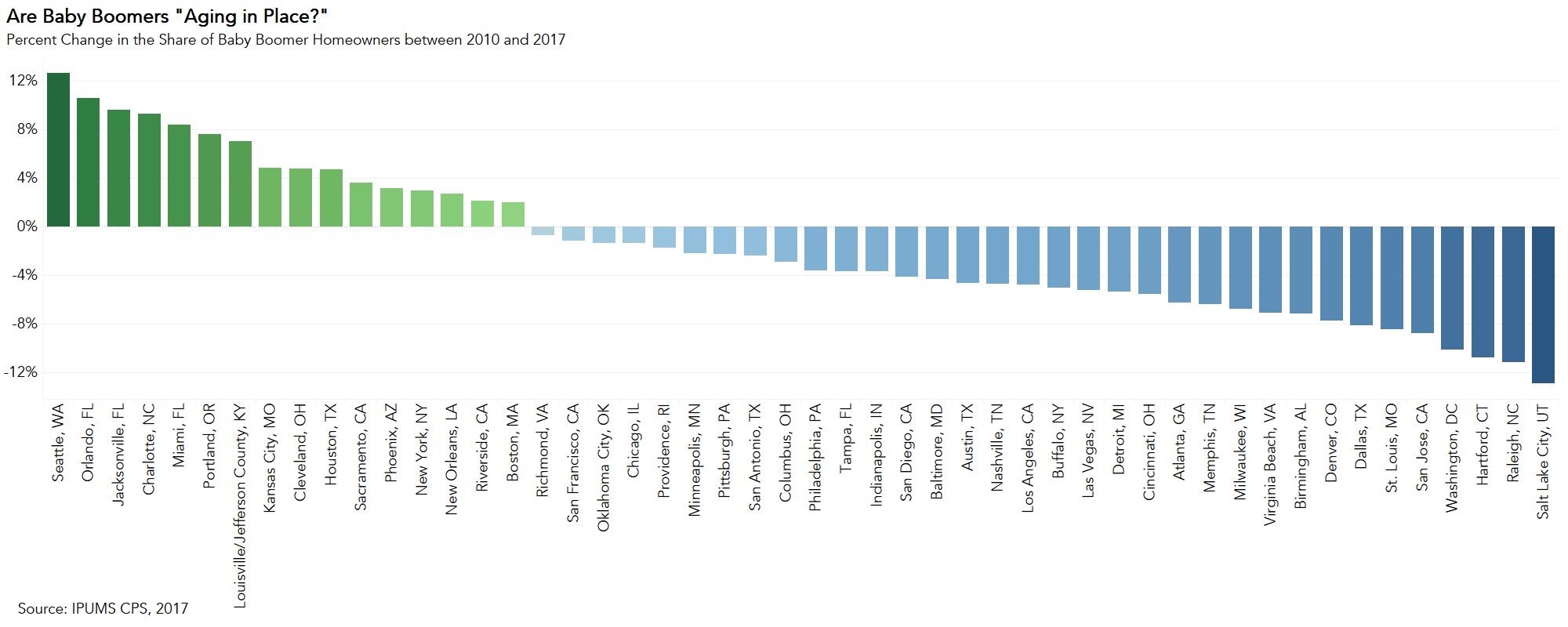

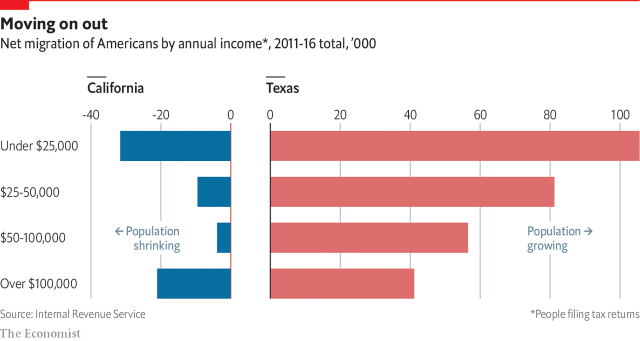

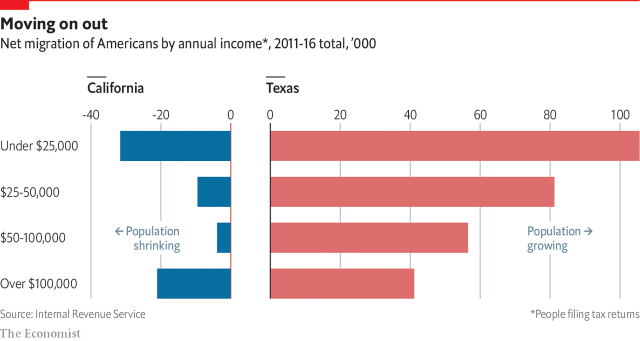

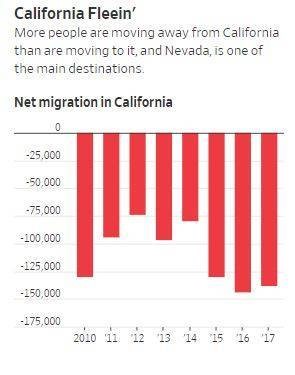

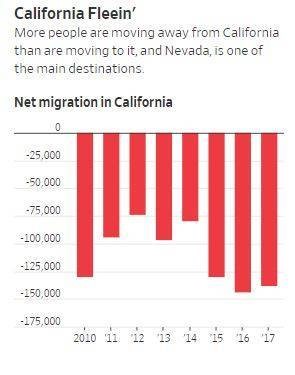

Fast forward to today, when we seem to have Manifest Destiny in reverse, at least in part. People are leaving the coasts, its high cost of housing, higher taxes, and crime, and heading to lower-cost states in the South, Southwest, Southeast, and parts of the Northwest. Data is a bit hard to come by, but according to the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, about 1.1 million people moved from high-cost metro and coastal areas to either mid-size cities or rural areas since the start of the pandemic.

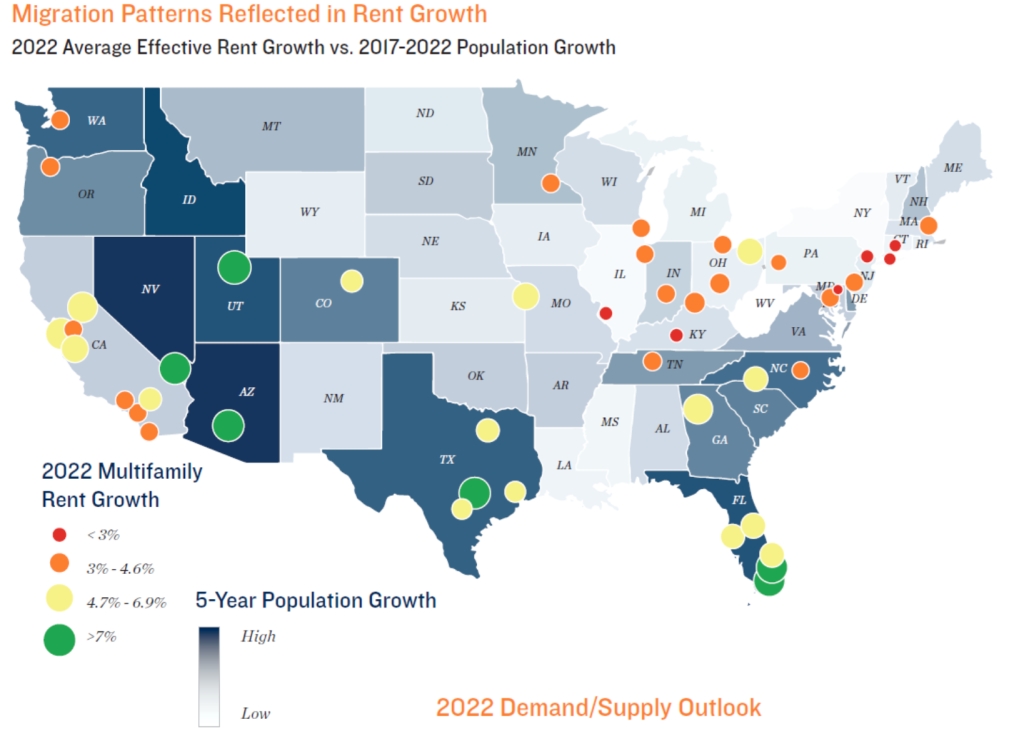

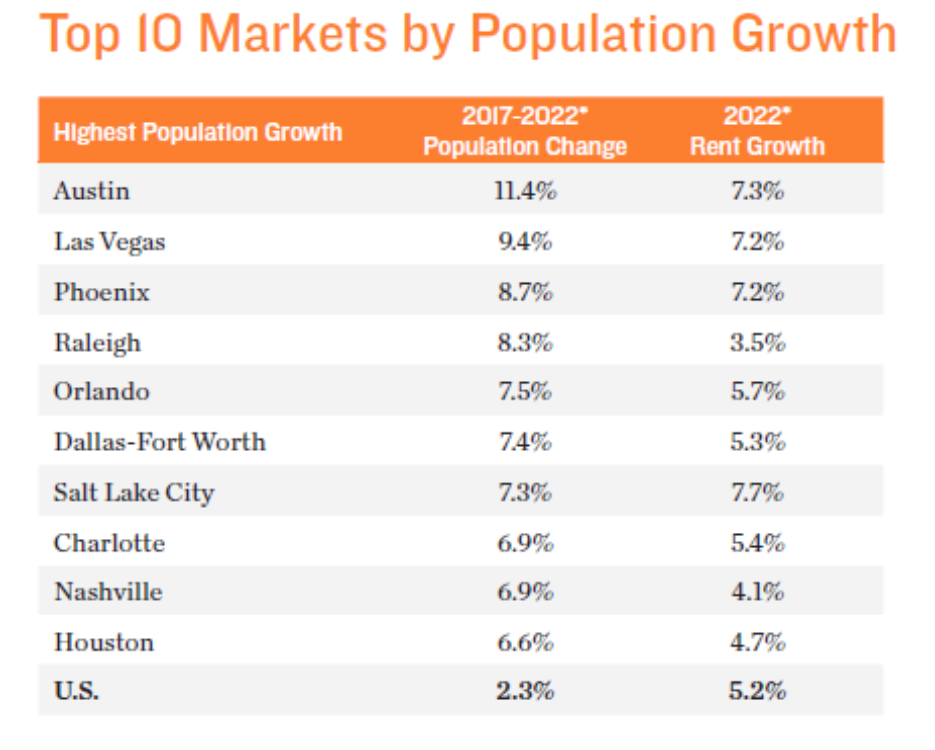

Texas, Arizona, Florida, Colorado, Montana, Oregon, and North Carolina all gained population according to the most recent census, while California and New York have lost residents. Not surprisingly, these population trends inform projections for rental growth in 2022 and beyond.

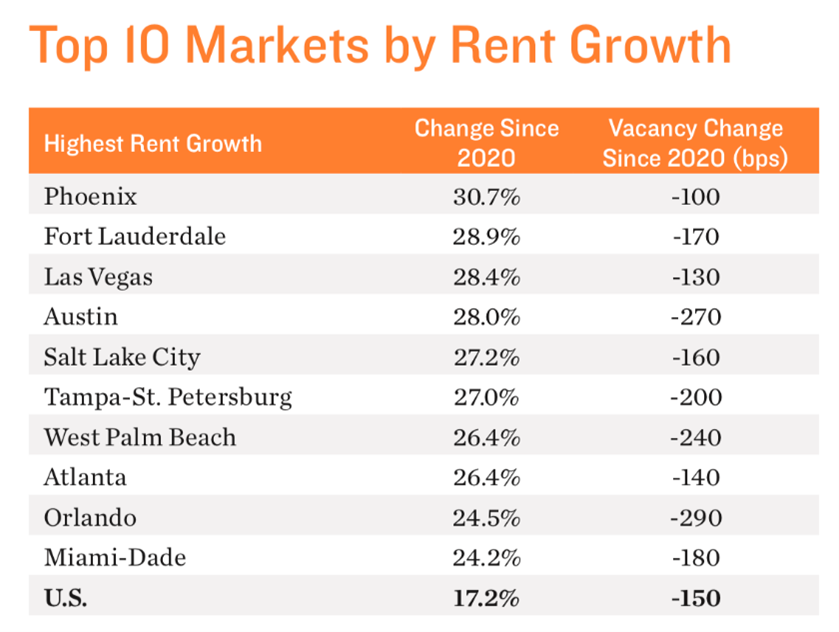

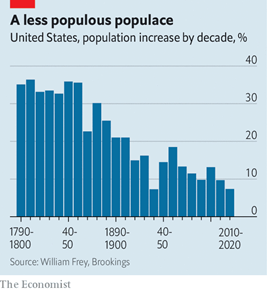

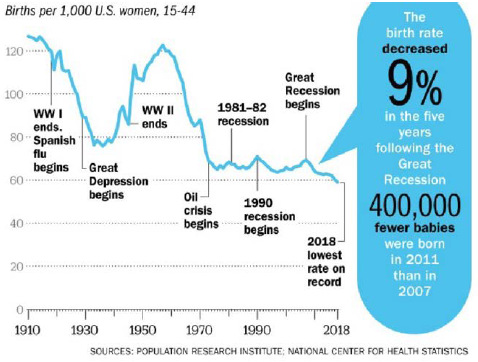

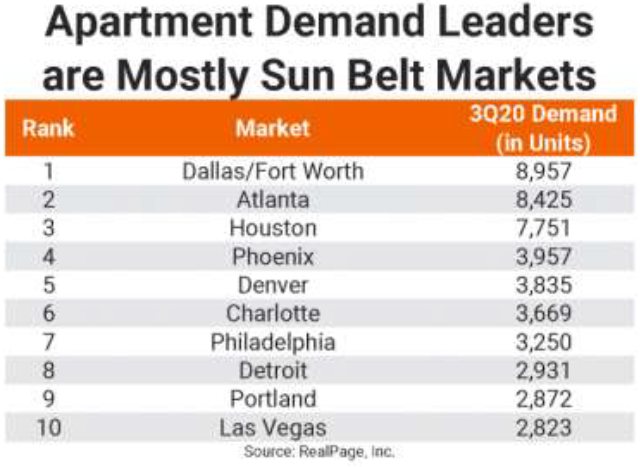

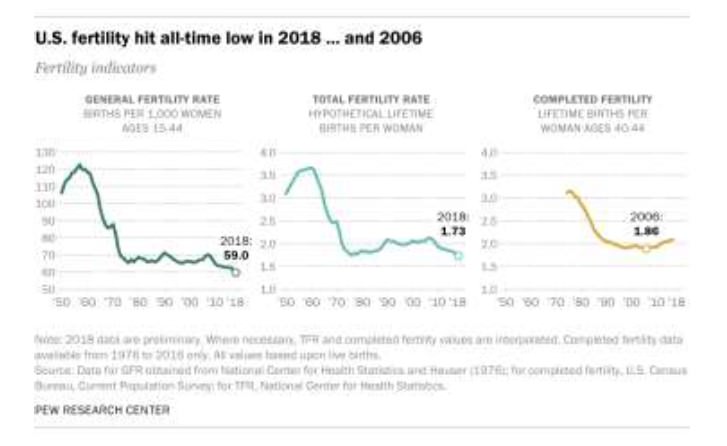

It is no surprise that the Sunbelt will likely see the greatest population growth in 2022, perhaps 250,000 new households. However, I am less sanguine about all these rosy rental growth forecasts, due to the uncertainties I have already discussed. As many of you know, we sold most of our Texas portfolio late last year because we were unable to achieve the sort of rental growth that we had predicted, in part because supply was able to mostly keep up with demand. In any event, many of the same locales that have been popular destinations in recent years from Phoenix to Vegas to Tampa to Atlanta to Sacramento will continue to be popular according to Freddie Mac. On a more macro-level, growth in the U.S. population continues to decline, a trend I have discussed for some time now, continually confirmed by new data.

This reality will have longer-term growth implications to be sure, perhaps another reason I don’t think Elon Musk has to worry too, too much about the need to colonize Mars, although I imagine numerous value-add investment opportunities await us there and elsewhere.

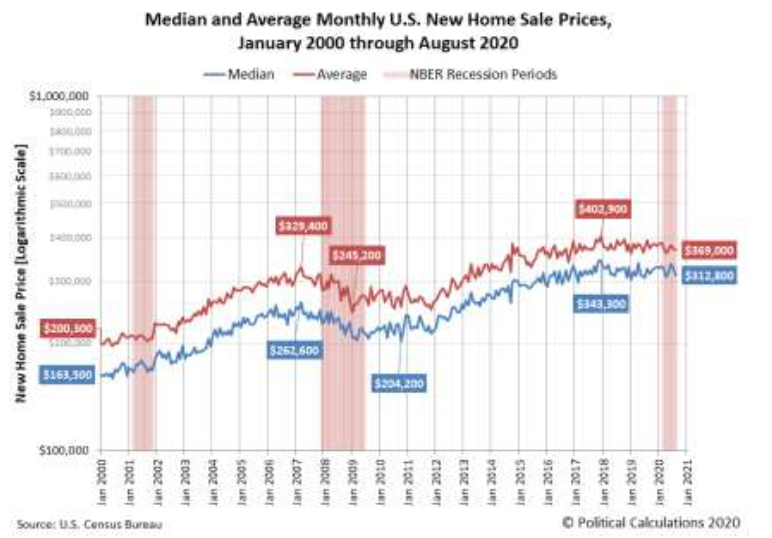

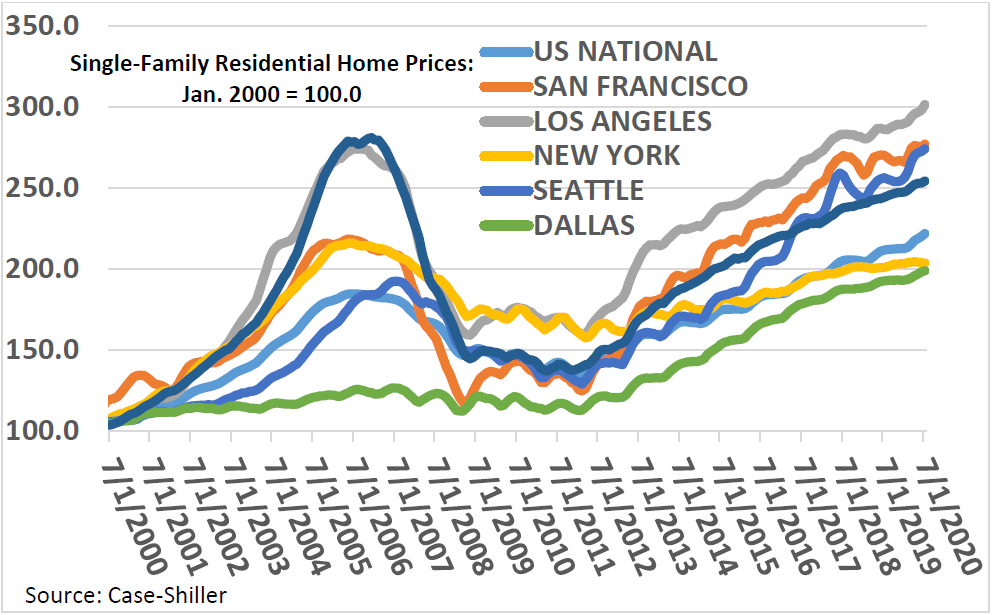

And single-family home prices in 2021? Wowza! But 2022 will likely look a whole lot different…

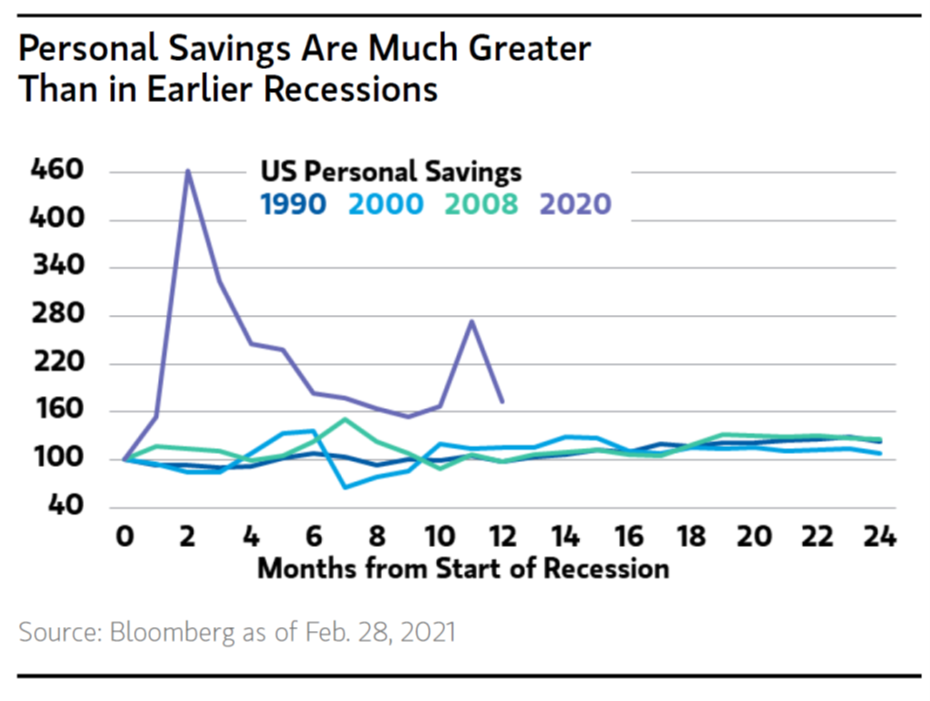

2021 was simply a remarkable year for the single-family residential market, with every single state realizing higher home prices. Just imagine that home prices in Arizona, Florida, and Idaho, rose 28.6%, 25.8%, and 25.5% in one year, respectively. “Wowza” really is the right word. One almost feels sorry for poor Alaska, which only experienced a 7.5% rise in home prices. The single-family market benefitted from an almost perfect storm of price drivers: record-low interest rates, increased household savings during the pandemic, a rising stock market, remote work, millennials entering homebuying years, institutional buyers loaded with capital, and reduced inventory and new supply.

However, these sorts of increases are not sustainable, and in the face of higher inflation and mortgage rates, slowing economic growth, the lingering pandemic, and broad uncertainty – economic and political –home prices are likely to remain flat this year, best I can foresee.

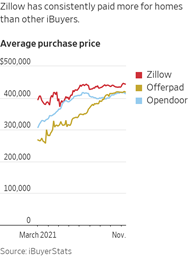

One impetus for higher home prices in 2021 was Wall Street and all the institutional i-buyers (e.g., Zillow, OpenDoor, and OfferPad) which were scooping up homes left, right, and center before they began to suffer some serious acquisition-related indigestion. Mark one in the “I got it right” column, as I have consistenly expressed pessimism about their strategies, basing purchase prices and home values on mathematical algorithms, while they forewent due diligence and purchased homes willy-nilly, for all cash and with quick closes. As though buying a home is like buying bubblegum at Walgreen’s. Even if their mathematical models were accurate, I could not detect a sustainable, scalable business model, especially in an economic downturn. It is equally likely that their models were a bit of GIGO, “garbage in, garbage out.”

Exhibit A for this colossal mess is Zillow, which announced a complete exit from the home-flipping business and is now offloading some 7,000 houses for $2.8 billion, on which it is expected to take a meaningful bath. Keep in mind that about 5.6 million single-family homes are sold in an entire year in the U.S. (plus about 700,000 condominiums). Whether their selling activity will depress prices in certain markets remains to be seen, but can we be surprised that they appear to have bought the most homes in Phoenix? From what I understand, a New York based investment firm has agreed to buy 2,000 of the homes from Zillow, so perhaps it depends on what this firm decides to do with them.

And sure enough, Zillow is not alone, as their competition is also starting to sell. Economics 100 tell us that this increased supply will negatively impact pricing, at least on the margin.

Meanwhile, more favorable longer-term trends in the single-family market persist, including a lack of buildable lots. Back in 2004 to 2005, homebuilders collectively generated new home sales of about one million units. And today? About 800,000. Will Rogers quote about “buying land because they are not making any more of it” was prescient. In a recent survey, about three-quarters of developers described the number of buildable lots in their markets as “low” or “very low”.

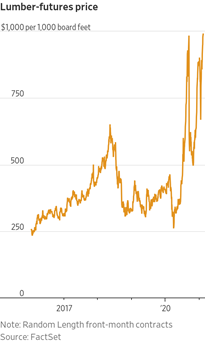

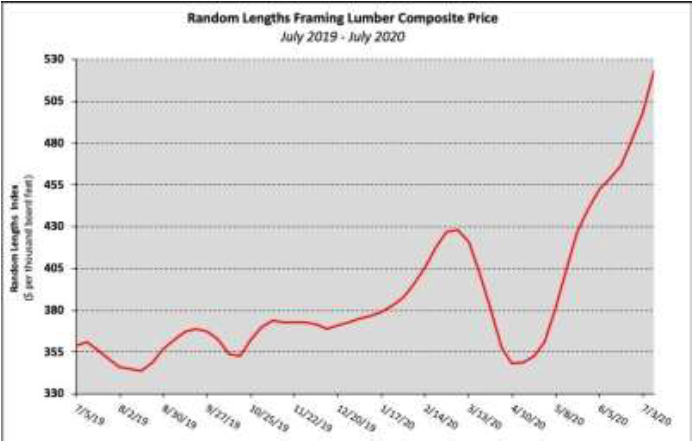

Meantime, supply chain and labor woes have provided and will continue to provide some downside buffers to single-family home prices. The cost to build a home is up about 20% over the past year, and most developments are at least two months behind schedule. I am sure more than a few of you have been experienced the supply chain challenges first-hand, perhaps a delay in the delivery of a washer and dryer or some other home appliance. We have. How long it takes for supply chains to return to normal is anyone’s guess, but given my penchant for cynicism, I am betting it will take more time than less.

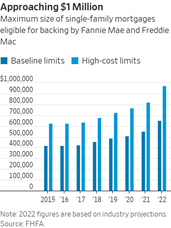

In other single-family housing news, I recently read that Fannie Mae is going to increase the size of home mortgages that it is willing to back, to nearly seven figures, reflecting the obvious, that its previous ceilings were impractical in the face of higher home prices. As of now, the maximum loan limit is $647,200, so whether they follow through remains to be seen. Given that some 60% of single-family homes purchased in the U.S. are financed through Fannie, the change would be impactful.

Regardless, I believe home prices will be mostly flat this year or will trade in a modest range (up or down a couple of percent). I certainly don’t see a repeat of 2021, but on the other hand, I don’t see any impending collapse. The banks have been more prudent in their lending standards, supply remains low, and even with their recent rise, mortgage rates relatively low by historical standards.

Location, location, location? More like inflation, inflation, inflation….

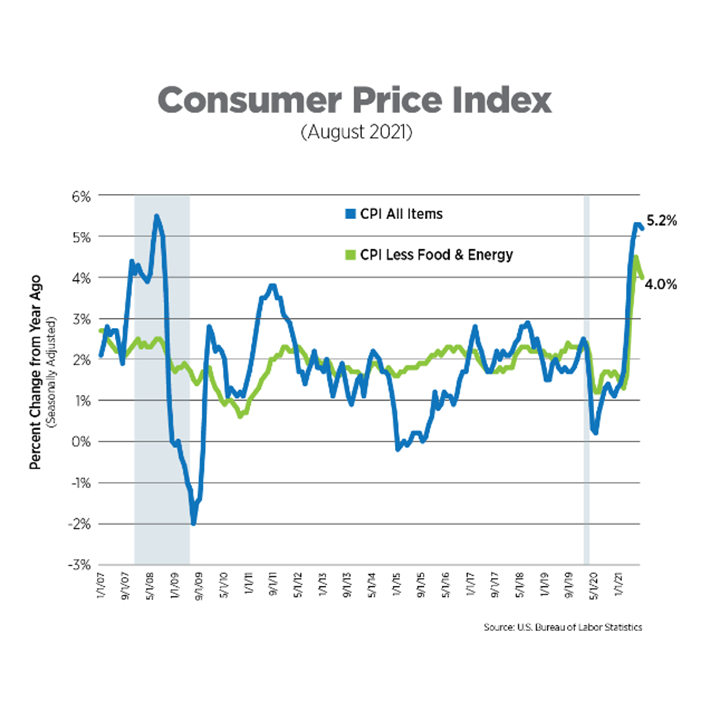

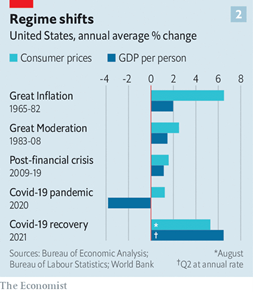

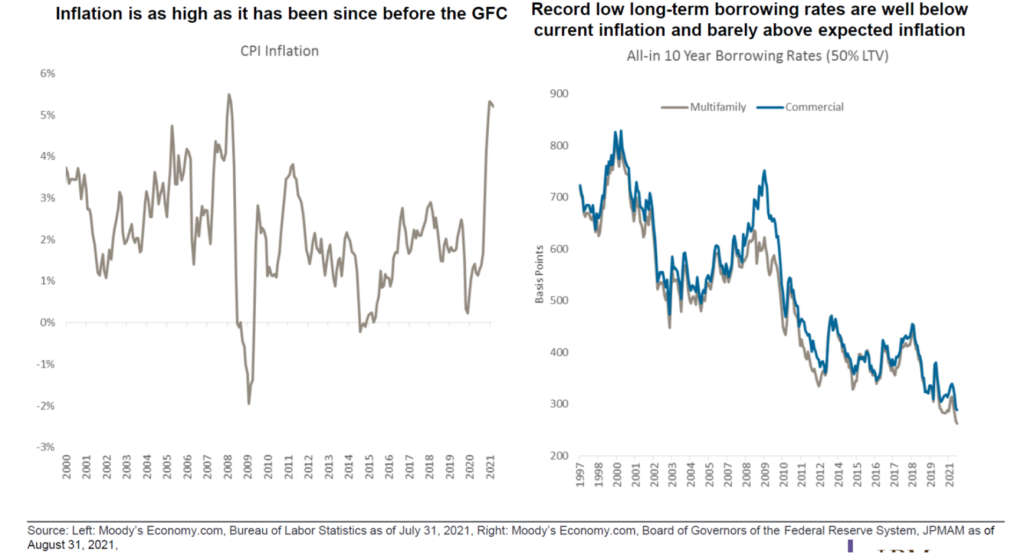

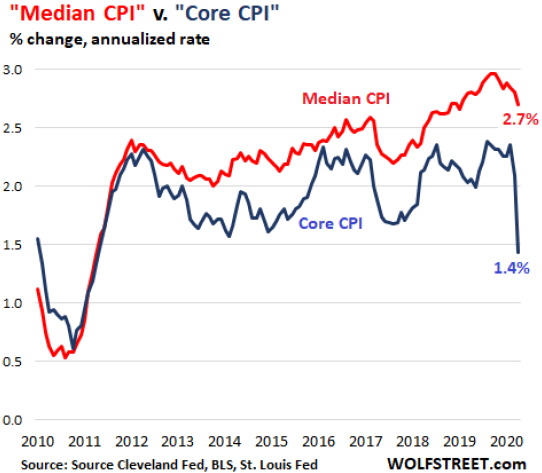

Unless, you have been living under a rock (if you have, I hope it is not in the Sunbelt as it would get awfully toasty under there), rising prices and inflation have been on every consumer, investor, and policy maker’s mind of late, as we have recently witnessed inflation rates not seen for some 40 years. Consumer prices rose 7.0% in December, as compared to the prior year, even higher than November’s 6.8% rise, and levels not seen since 1982. One picture tells 1,000 words, and it’s not pretty:

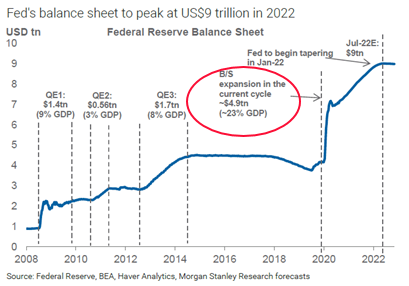

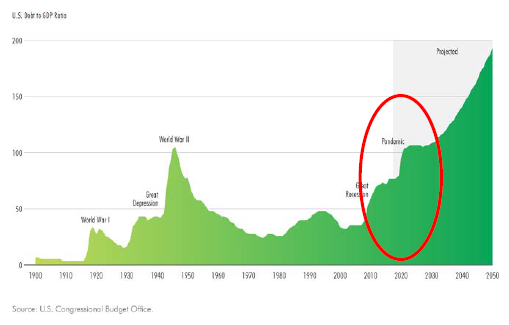

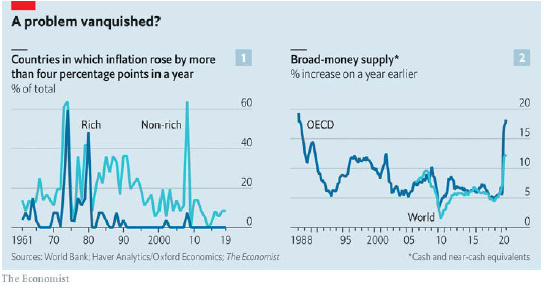

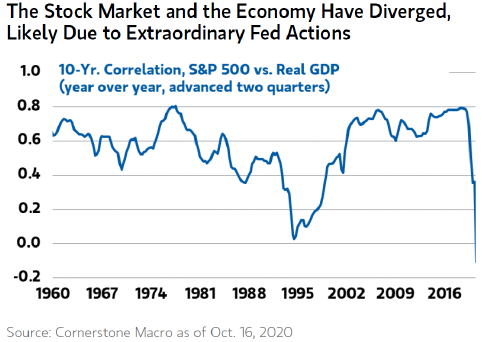

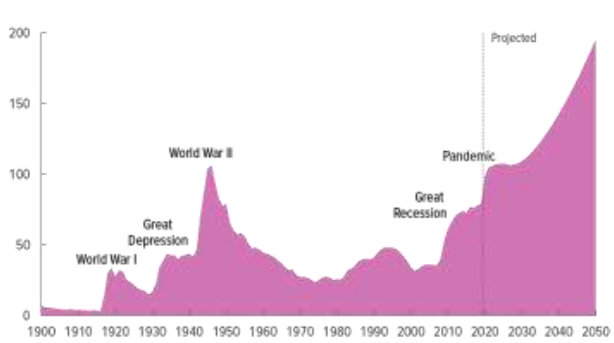

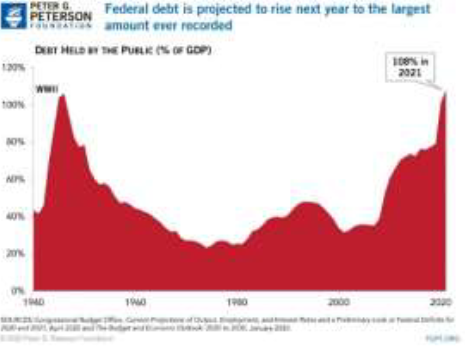

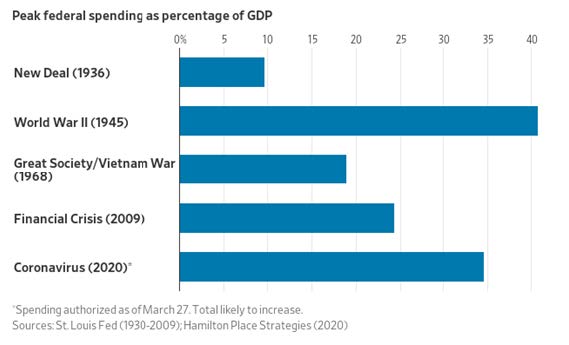

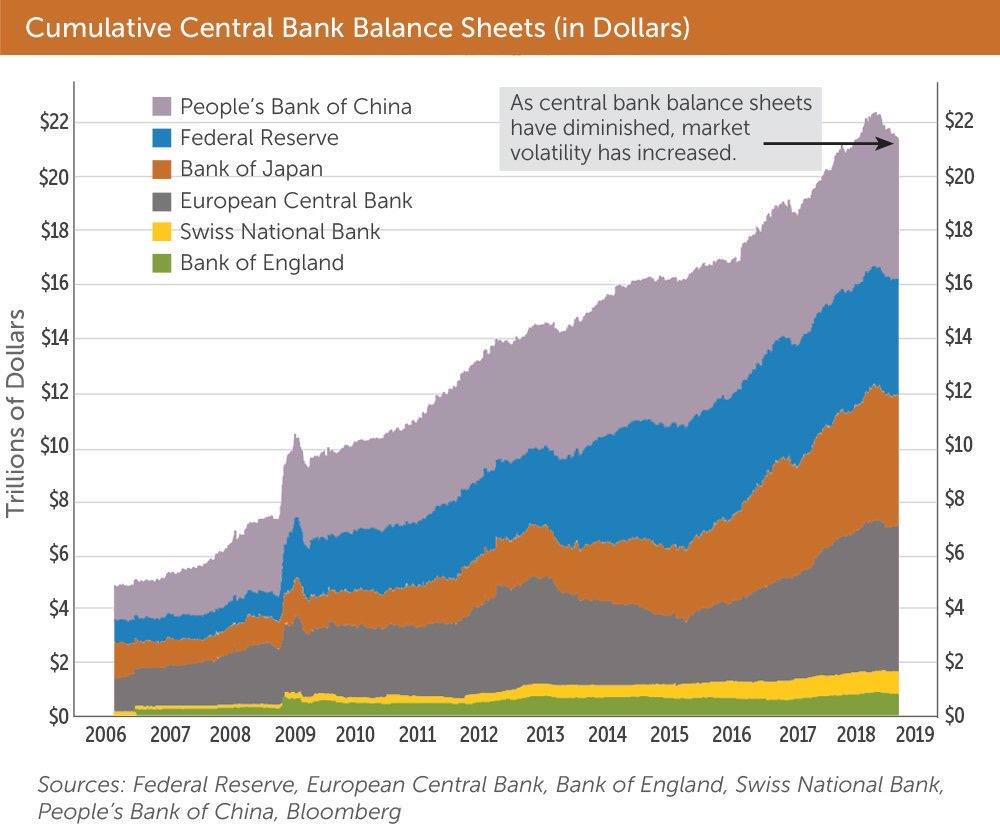

Here’s the thing. After a year of brushing off these higher prices as “transitory,” it is proving anything but, and can we really be shocked? The Fed has printed money for over a decade like they would never run out of toner. Does anyone think that the bubbles we have witnessed in speculative assets (see November Clear Insights newsletter) and higher assets generally (including, yes, real estate prices) have strictly been based on fundamentals? Sure, those have been highly influential, too, but let’s not pretend that the accommodative Fed has not played its part.

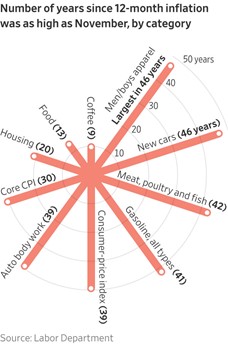

Here are another couple of interesting pictures which tell the inflation story, and in ways that I found unique and interesting. The first summarizes – across various categories (i.e., housing, food, gasoline, new cars, wages) – just how many years it has been since inflation rates were as high as what we have recently witnessed. Let’s just say that it has been…a while.

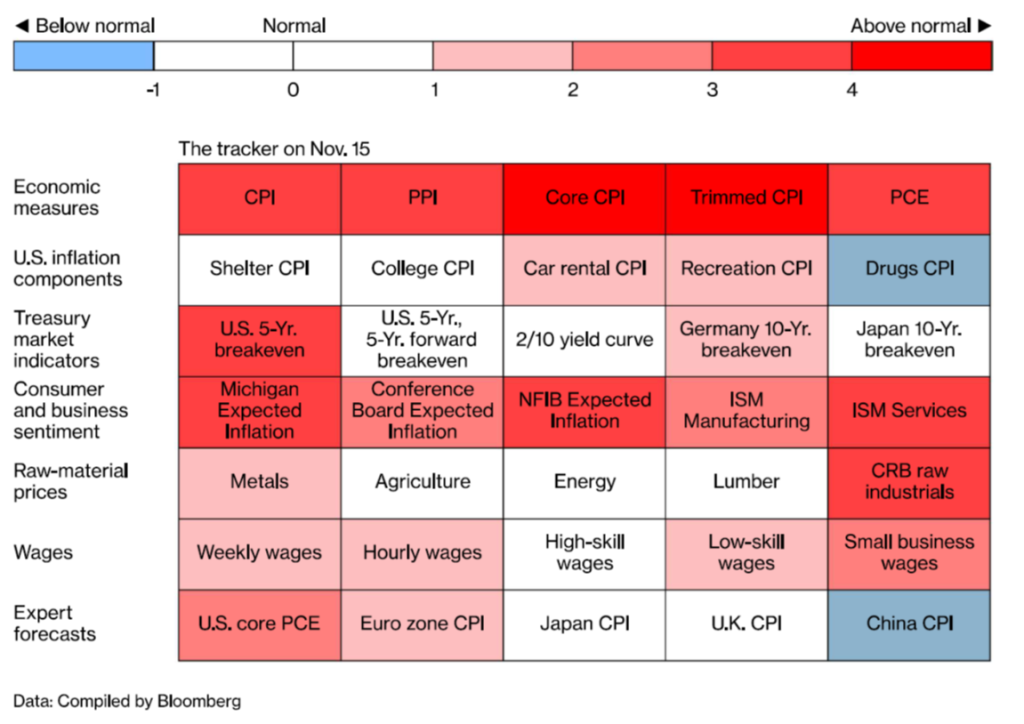

The second presents similar data, in a different way, but with the same conclusion. Prices, wages, raw material prices, etc. are all experiencing well above normal price or rate increases.

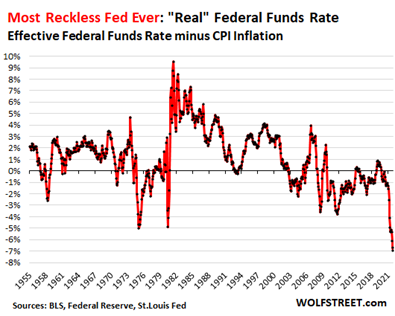

Perhaps the Fed mandate to promote maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates is asking too much, as Jerome Powell and his predecessors are not Houdinis, and 2022 is most certainly not 1982, when the Fed Funds rate was 14.2% (that is not a typo), and “Quantitative Easing” (significant asset buying) was not in the lexicon. Today we have this unique situation where the Fed Funds rate is something like 0.08% and the Consumer Price Index over 7.0%, resulting in an inflation-adjusted, effective Fed Funds Rate of negative 6.96%, something never seen previously.

So, what is the Fed to do? Somewhere in the back of my mind, I am now hearing the Naked Eyes song from 1983 (no coincidence, perhaps), “Promises, Promises,” because just last week, the Fed announced that they will “tighten monetary policy” at a much faster pace than thought a month ago. Median forecasts are for the Fed to raise interest rates three times in 2022, starting in March, to 0.75-1.00% by year end, up from the two hikes forecast in December. We shall see.

What is interesting is that when the Fed made its last announcement and plans for two rate hikes in 2022, the markets essentially yawned. But not this time. If I have one other concern is if inflation, like everything else these days, becomes “politicized,” and blame for higher prices is placed on “greedy” corporations or “rigged” markets, instead of other obvious factors, like supply chain disruptions, pent-up demand, and the Fed’s money-printing ways. We should all be very wary of those calling for “price controls” as a policy response, because we must remember our economic history, like President Nixon’s predictably ill-fated efforts to freeze wages and prices back in the early 1970’s.

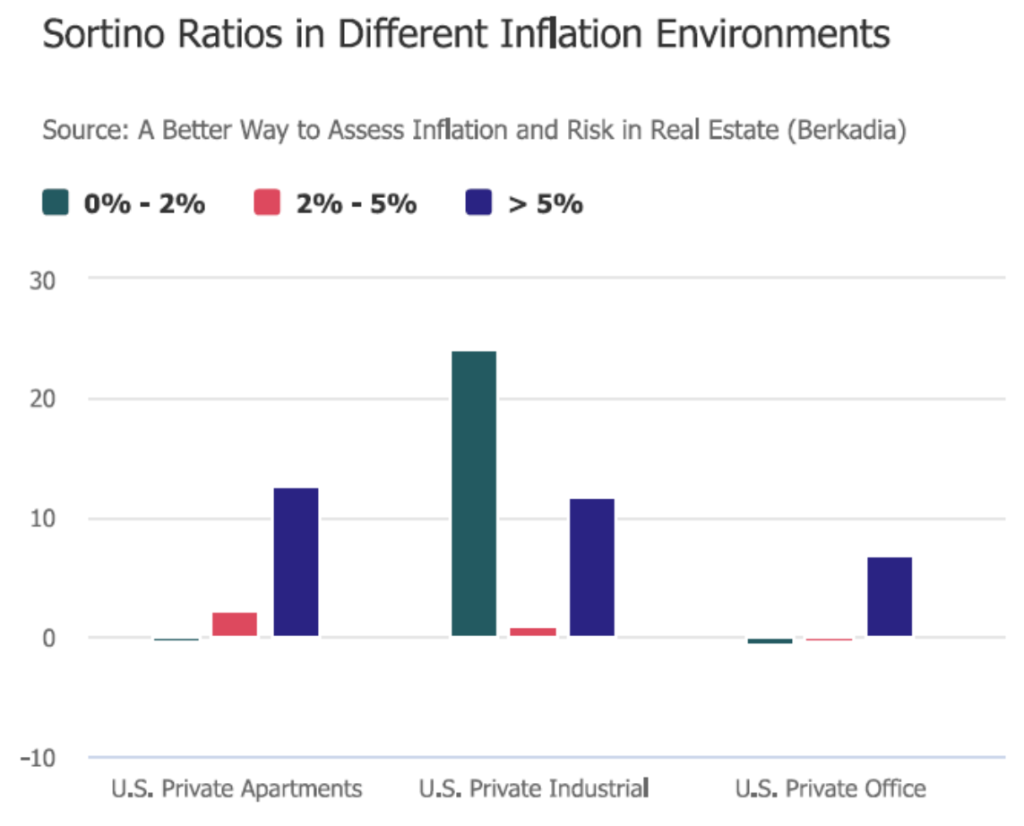

Because all this inflation talk can be fear-invoking and sobering, I would like to put one positive spin on the data, relating it back to what we do for a living. Thankfully, real estate has historically proven to be a good inflation hedge, something I wrote at length about in the August edition of our Clear Insights newsletter. Perhaps not surprisingly, those classes of real estate assets in which landlords are able to adjust rental rates more quickly in response to inflationary pressures do well. Historical data indicates that multifamily and industrial assets fare best in these environments, perhaps explaining, in part, their outsized performance in recent years.

In any event, higher inflation rates and a less accommodative Fed will act as significant headwinds to financial markets this year, and while multifamily investments will benefit from higher mortgage rates, making homes less affordable, these higher rates will impact asset underwriting and both purchase and projected exit cap rates.

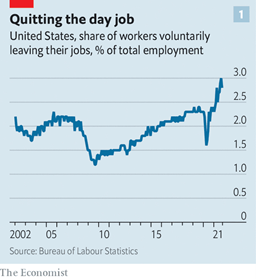

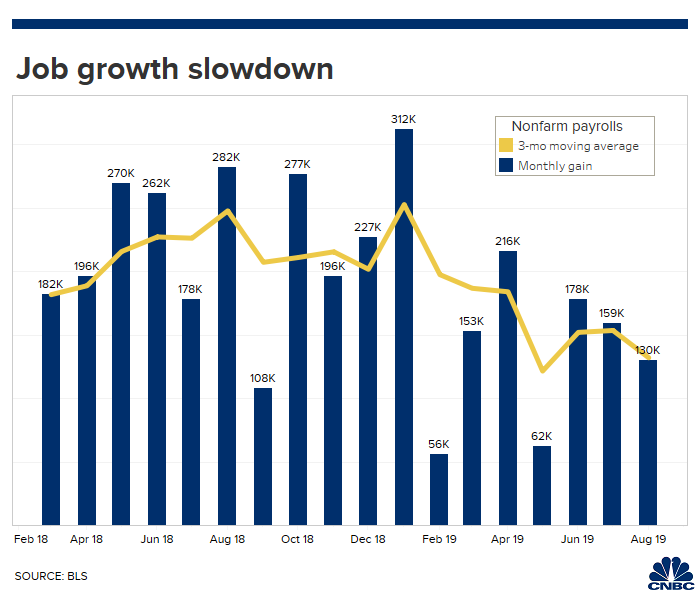

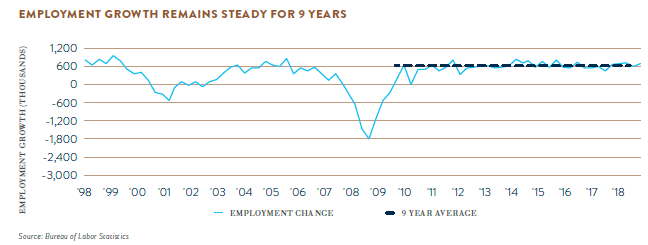

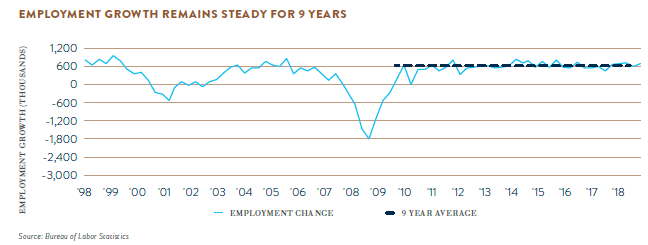

While the employment picture has certainly brightened, folks are quitting their jobs in record numbers and who can blame them?

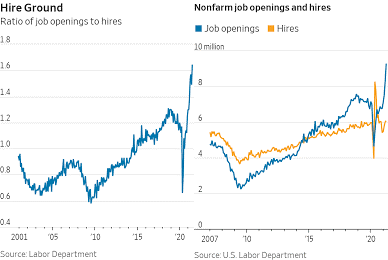

In one week, I read several articles which really captured what is happening in the job market. One was “The Great Resignation,” describing the record number of people, especially the young, leaving in their jobs due to everything from low wages, poor treatment, COVID, and new professional or personal opportunitites (e.g., education, cryptocurrency/NFT trading). As of year end, there were some 12 million job openings (including several openings at Clear Capital), as compared to about 7.5 million unemployed. In 2021, some 4.4 million left the workforce.

Another article that crossed my desk (or desktop) was “Companies Plan Hefty Raises for Workers.” While labor strikes at John Deere and Kelloggs were settled in November, the settlement terms spoke volumes. The Illinois manufacturer’s United Auto Workers voted in favor a new six-year agreement that included an $8,500 signing bonus and a ten percent wage increase, along with enhanced retirement and performance benefits. And then in following weeks, I read about strikes involving the Seattle Carpenter’s union, certain Denver-area grocery store workers, and some 17,000 BNSF Railroad employees. From Wall Street to Main Street, from London to Berlin to Los Angeles, wages are headed higher.

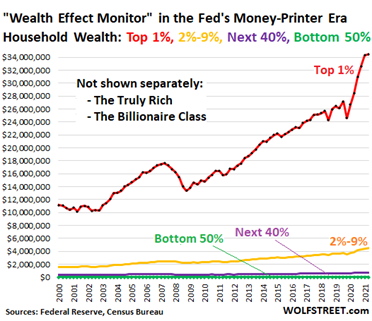

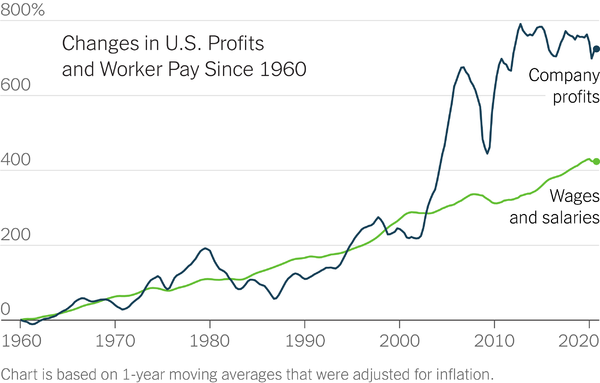

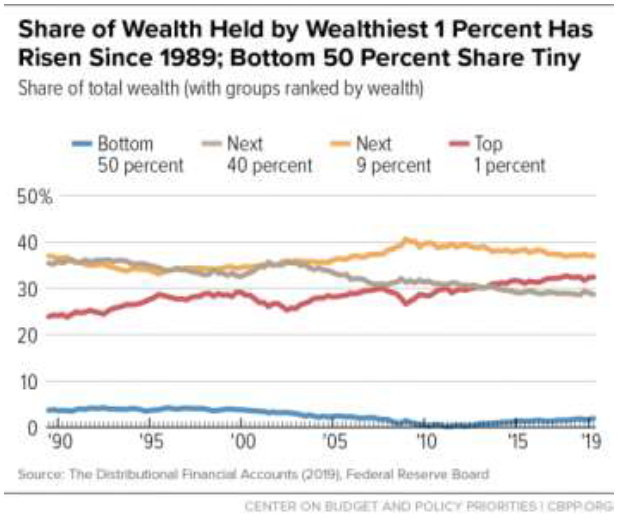

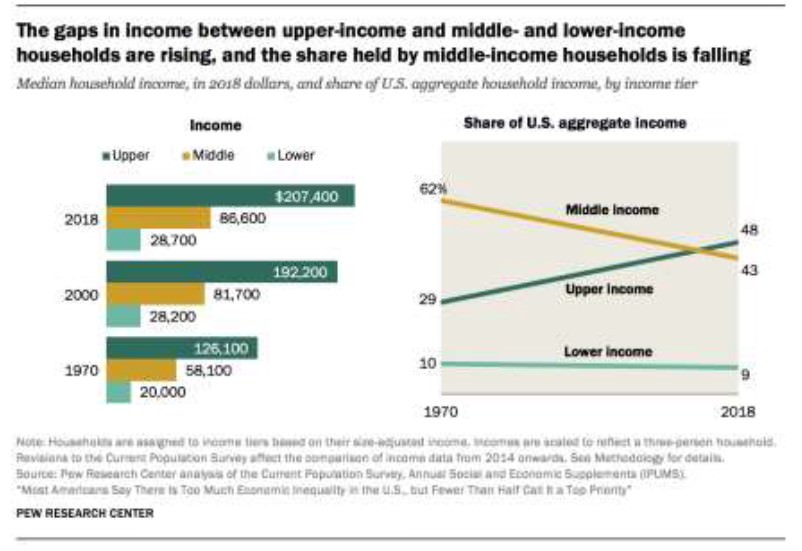

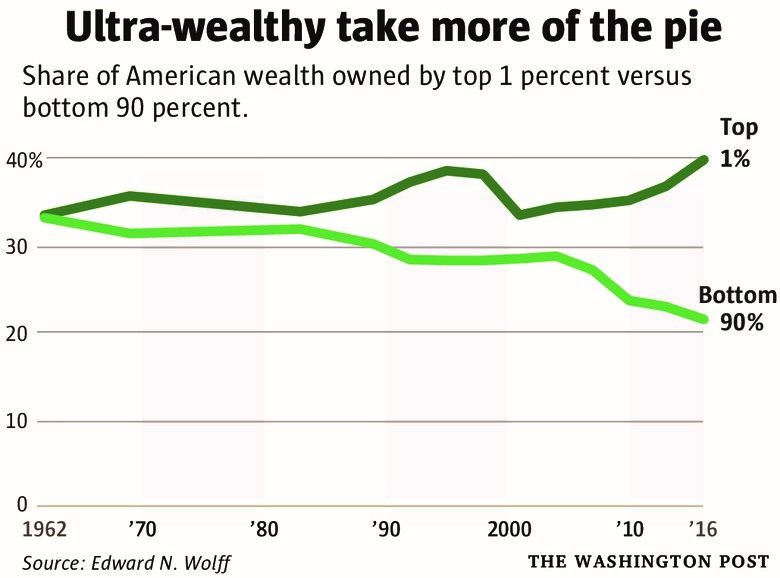

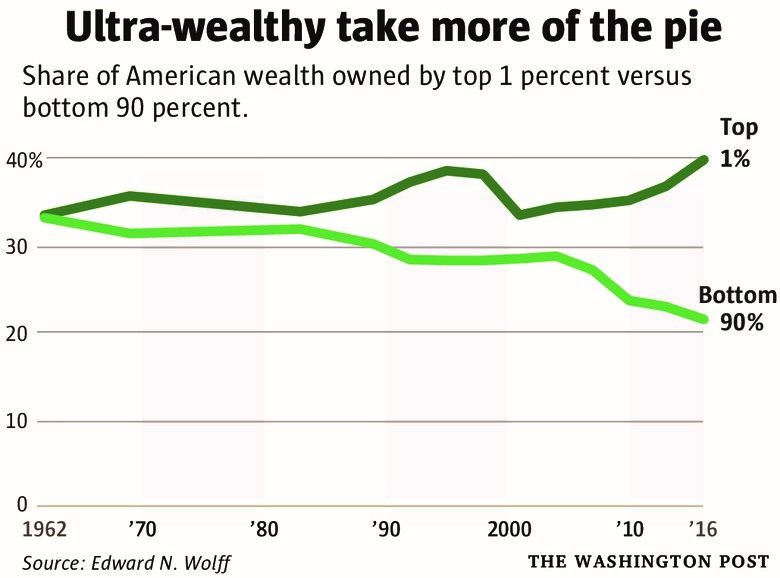

In the face of increases in food, energy, and housing prices, it is a necessity, and from my view, about time. I have long written about expanding wealth inequality and its perverse consequences. The graph below tells the story, and how we need to return to something more balanced when it comes to household wealth.

On the public policy front, there are just a couple newsworthy items from the fourth quarter

Somehow, some way, politicians here and everywhere provide fodder for these quarterly diatribes, usually suggesting, proposing, or implementing harebrained or shortsighted salves to address longer-term systemic issues. Here are a couple from the fourth quarter that fit the description:

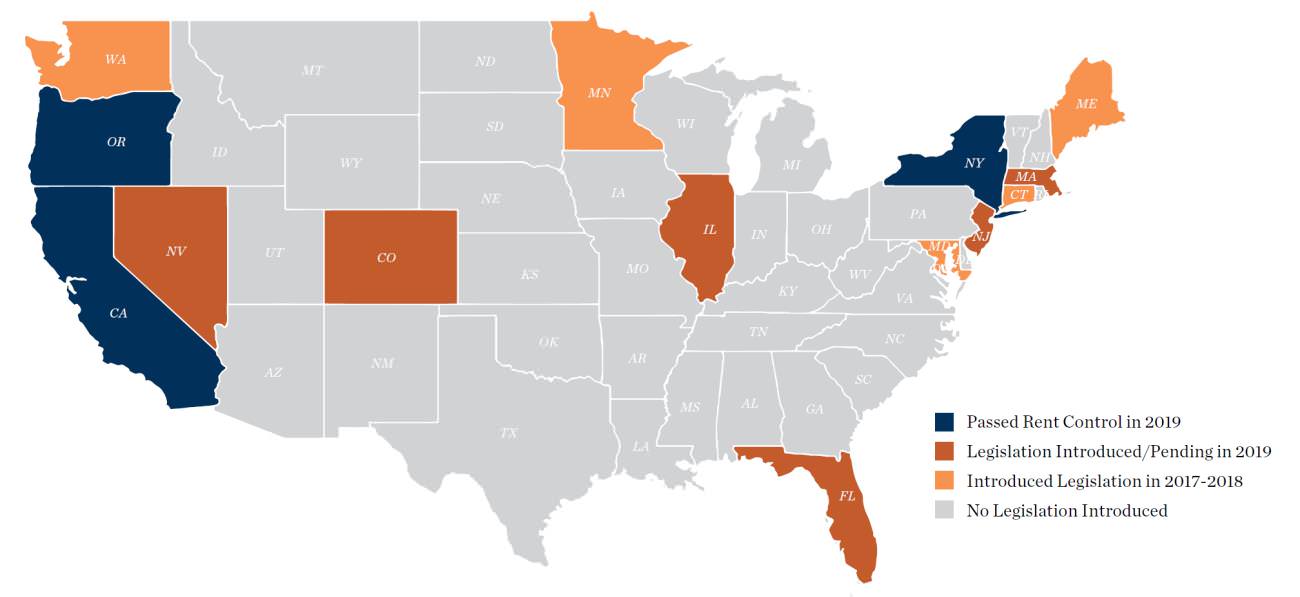

- For all units subject to rent control (about 650,000 units, three quarters of housing stock), the city of Los Angeles decided to freeze residential rents until 2023. Yes, you read that right. No rent increases until 2023, decided upon at the end of 2021. How can this be sound economic policy, let alone Constitutional? Perhaps it was this story juxtaposed against another that broke on the same day that really got my goat, where a local anti-growth group is seeking to block a separate proposed housing plan by the city, which would allow for greater housing density and potentially add 500,000 units to the rental stock. What developer in their right mind would want to develop units in a city which is incessantly trying to rein in higher rents through price controls?

- From Los Angeles to the White House, from New Zealand to Ireland, politicians are mulling or implementing restrictions on who can purchase a home or adding taxes and fees to address housing affordability. Los Angeles City Council is supposedly considering a proposal that would not allow entities (e.g., corporations, limited liability companies) to purchase single-family homes, a completely impractical, if not unconstitutional policy. During the fourth quarter, New Zealand passed legislation eliminating certain tax breaks for property owners and investors and Ireland implemented a 10% tax on bulk buying of homes, which represent less than two percent of transactions.

None of these policies will meaningfully impact housing prices or rents. In this prediction, I feel pretty darn confident.

And despite this memo’s length, I will end with just a couple quick tidbits from the quarter that I found interesting or noteworthy

- By admission, I am always a late adopter when it comes to technology, and while I have an iPhone, I won’t tell you which model I own other than it is a few iterations behind. Anyhow, during the quarter, I read that Ukraine (of all places), may allow for Non-Fungible Tokens (NFTs) to signal proof ownership for certain financial assets or transactions, including the exchange of real property deeds, bypassing traditional intermediaries. I have always found title insurance and the entire recording process for deeds and real estate ownership to be inefficient, cumbersome, and excessively costly. I don’t know whether technology and real estate will finally meet, as they have been reluctant bedfellows. We shall see.

- In response to supply chain bottlenecks, CEOs are rethinking their global production playbooks, which could result in greater onshoring of manufacturing and distribution activities. If such comes to pass, the industrial market will receive another shot in the arm. Industrial rental rates have already doubled in the last 24 months.

In closing, I can’t say I am altogether unhappy to see 2021 in the rearview mirror, though the way 2022 has started, I am already longing for the good old days…all the way back to December. While I am a perpetual optimist, I am not one to simply don rose-colored glasses because my VSP insurance covers their cost. 2022 will likely present challenges, if just because higher inflation, a less accommodative Fed, the lingering pandemic, and the midterm elections increase uncertainty and present tailwinds. And let’s be candid. Financial and real estate markets have performed so well for so long, more modest expectations and returns ought to be in the cards regarldess.

What this means for Clear Capital is simple. We will have to be especially mindful and critical when underwriting potential acquisitions, stress-testing key assumptions and what-if scenarios. We will likely monetize certain assets in certain markets, where we have realized projected returns and see limited upside, perhaps entering new markets as we remember hockey great Wayne Gretzky’s simple message, that success is figuring out where the puck is going and not where it has been.

Finally, and as always, thank you. Thank you to our investors, partners, vendors, employees, friends, and the entire Clear Capital and Clarion Management teams for their support and extraordinary efforts during a challenging year. I remain grateful and feel very fortunate to work alongside such a talented and dedicated group of individuals.

Best,

Eric Sussman

“It’s no wonder that truth is stranger than fiction. Fiction has to make sense.”

– Mark Twain“You see, but you don’t observe. The distrinction is clear.”

– Sherlock Holmes (Arthur Conan Doyle)

As a kid, I devoured mystery and detective books, and might even have been considered a Hardy Boys groupie. I read every new release in the series almost as soon as a new one came out. In any event, no crime was too complicated or any mystery unsolvable for Frank, Joe, and the Hardy Boys’ high school chums, and they were coincidentally fortunate that their fictional hometown of Bayport, New York was so riddled with shady characters and crime syndicates. Perhaps if Bayport were a real place, Clear Capital might consider investing there as a contrarian, value-add play.

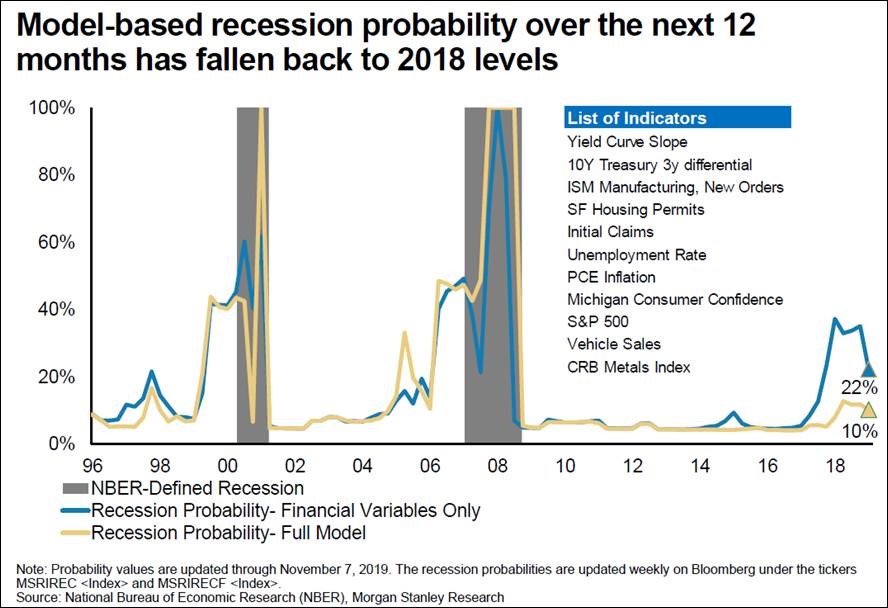

Fast forward to today, as I wade through and try to make sense of a barrage of complex, if not seemingly contradictory, third quarter economic data, I sure could use the Hardy Boys, Nancy Drew, Encyclopedia Brown, Sherlock Holmes, and their hangers-on to help answer the numerous questions and solve the mysteries that surround today’s markets and the economy:

- Is this recent bout of inflation we have experienced transitory or something longer lasting?

- Are we going to experience a repeat of the 1970’s “stagflation,” reliving the worst of two worlds, economic stagnation and higher prices?

- When will all the missing workers return to the workforce? At what cost?

- How much higher can asset values, including real estate prices, go?

- When will the Fed taper its bond-buying activities and/or increase interest rates?

- When will the bottlenecks surrounding supply chains clear?

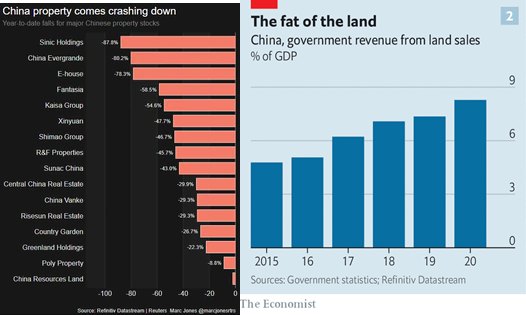

- Will Evergrande and other Chinese developers go kaput, with the impact felt in our markets?

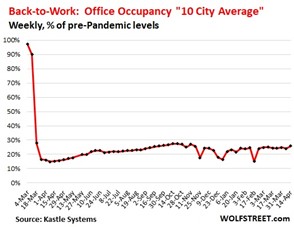

- Are we finally getting towards the end of the COVID-19 tunnel? What will the post-COVID workplace look like longer-term in terms of remote work?

- Will politicians at all levels actually and meaningfully legislate, and what impact might new laws and regulations have?

- Will there be a second season of Squid Game?

These are some weighty questions worthy of discussion, and though I recognize the limits of my psychic abilities, I will weigh in on each, with apologies in advance that I don’t have the Hardy Boys et al to lend an analytical hand or four.

Regardless of how these economic question marks and mysteries are solved and resolved, I remain confident that housing prices and rents – whether single- or multifamily assets – will be heading higher in coming months and years, with non-coastal markets continuing to outperform

I suppose it is a question of perspective of whether this prediction is a positive or negative.

For Clear Capital, investors, and others that own financial assets, including residential real estate, this prediction would certainly be welcome and positive. On the other hand, for those seeking to purchase their first homes and/or those concerned about housing affordability and homelessness (all of us, I imagine), this reality would also have certain perverse outcomes. It is truly a two-sided coin.

The third quarter was a very positive one for landlords and owners of residential assets, characterized by significantly higher housing prices and rents. Once again, several pictures tell the story, whether one is analyzing single- or multifamily markets. Prices and rents increased and increased sharply.

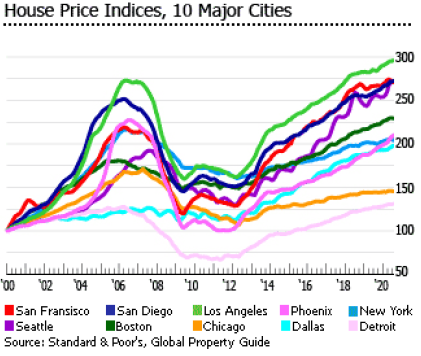

Nationally, home sales surged in September, with existing home sales up 7% (versus August), amidst already record-high prices, which were up another 1.4% from the prior month, and over 19% year-over-year. Here in Southern California, prices were up 1.3% in September, with the median sales price reaching $688,500, up 12.9% from the prior year.

In 182 of the 183 residential markets tracked by the National Association of Realtors, prices were higher year-over-year. In Austin, nearly 2,700 homes have sold for $100,000 or more above asking prices thus far in 2021. And in another telling anecdote, a Bay Area broker commented that she was not at all surprised that a home listed for $850,000 received six offers above its asking price, ultimately selling for seven figures, but that she was surprised that she received one offer below the asking price. I cannot recall ever hearing an agent being surprised at receiving an offer below its listing price.

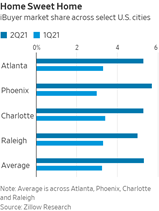

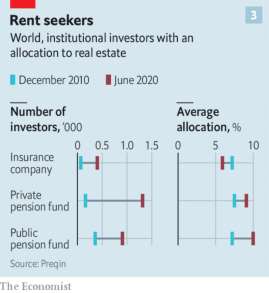

And who is doing all of this buying? Well, in certain markets, it is institutions, the Zillows, OpenDoors, Blackstones, and Invitation Homes of the world, and amazingly enough, more institutions are entering the fray (e.g., Flyhomes, Ribbon, Home-Light). Literally two days after I put the finishing touches on my last quarterly memo, I read an article about Tricon Residential, Inc., a Toronto-based company which already owns and rents about 25,000 homes, which announced that it is partnering with a Texas pension fund to acquire another $5 billion of U.S. houses to convert them to rentals. That is not a typo. $5 billion, which will theoretically allow for the purchase of 18,000 more homes, plus or minus. Institutions have already bought between 15 and 20% of all single-family homes sold thus far in 2021.

I cannot fathom how these business models or trends are sustainable. In fact, Zillow just announced last week that it was suspending its homebuying activities after buying 3,800 homes in the second quarter, resulting in a little single-family indigestion. Keep in mind that Zillow had announced plans earlier this year to acquire 5,000 single-family homes each month by 2024. Oops. Now I just hope that Zillow is willing to share their residential Pepto-Bismol with Tricon and others. Certain institutional investors, so-called “i-buyers” are buying homes sight-unseen, based strictly on mathematical algorithms (think “Zestimates” from Zillow).

The tremendous imbalance between demand and supply for housing, exacerbated by the impact of institutional homebuying, unparalleled liquidity, low rates, higher construction costs (e.g., labor and materials), anti-growth sentiment, and political shortsightedness will likely ensure that even higher home prices are in our futures.

Another interesting tidbit that caught my eye was that the top-performing single-family residential markets in recent years have been those with longer commutes to job centers (read: urban cores), according to the Brookings Institution. For the two years ended May 2021, home prices in neighborhoods with 70-minute commutes rose over 30%, strongly outpacing the 9.2% price gain and 2.5% price decline for markets 20 minutes and 10 minutes from job centers, respectively. The growth in such markets has led to those “exurbs,” areas that have seen significant net migration. Keep in mind that these trends pre-date COVID, which only accelerated them.

These exurb-type markets are really the ones worth watching, as they attract companies and employees alike, all seeking lower-cost locales. Take South Carolina’s Berkeley County, about 30 miles northeast of Charleston, which saw its population grow nearly 30% over the past decade, and local officials predict that the county’s population of 230,000 will grow to at least 350,000 in the next 20 years. While we have looked at investment opportunities in Berkeley County, Clear Capital’s investment strategy is absolutely informed by such data points, as we invest in exurbs closer to home.

And multifamily markets? Asking and effective rents hit record highs, with asking and effective rents nationally increasing 7.5% and 7.9% nationally, according to Moody’s Analytics REIS, the highest quarterly growth experienced, at least since the firm began to track such data in 1999. Net absorption in the third quarter exceeded the first two quarters of 2021 combined, with third quarter demand representing record highs, resulting in the vacancy rate for the top 79 metros tracked by REIS dropping 60 basis points, to 4.7%. Household incomes for new renters reached a new high, at more than $70K/year. Data from Yardi Matrix provides additional color on the broader data:

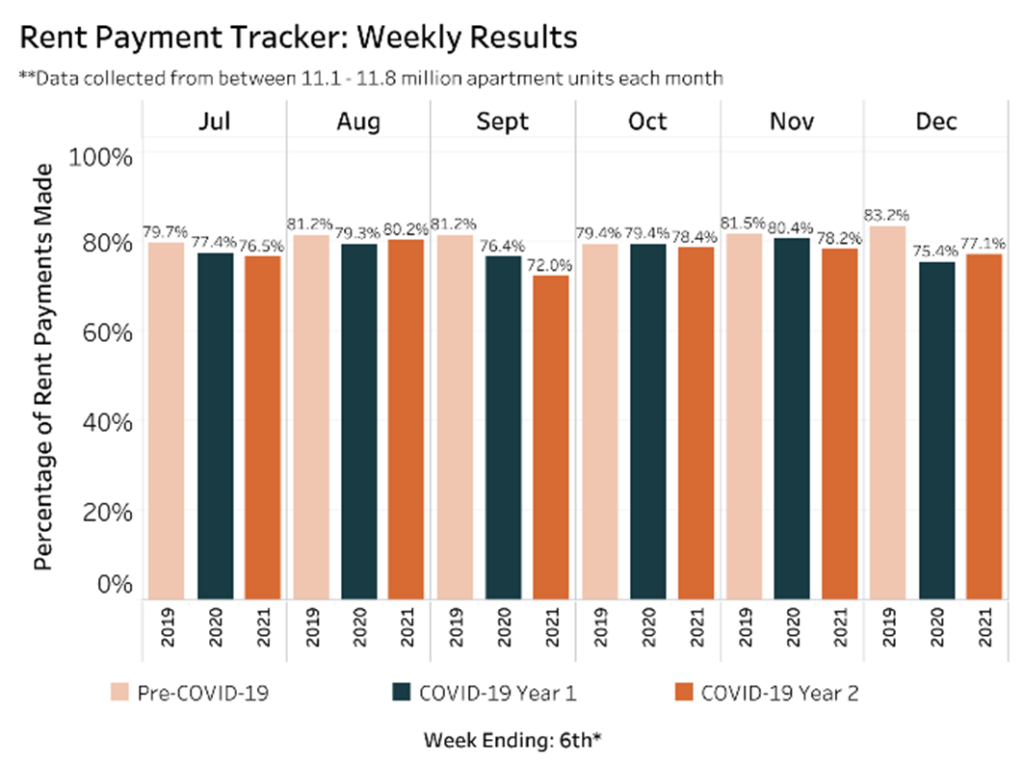

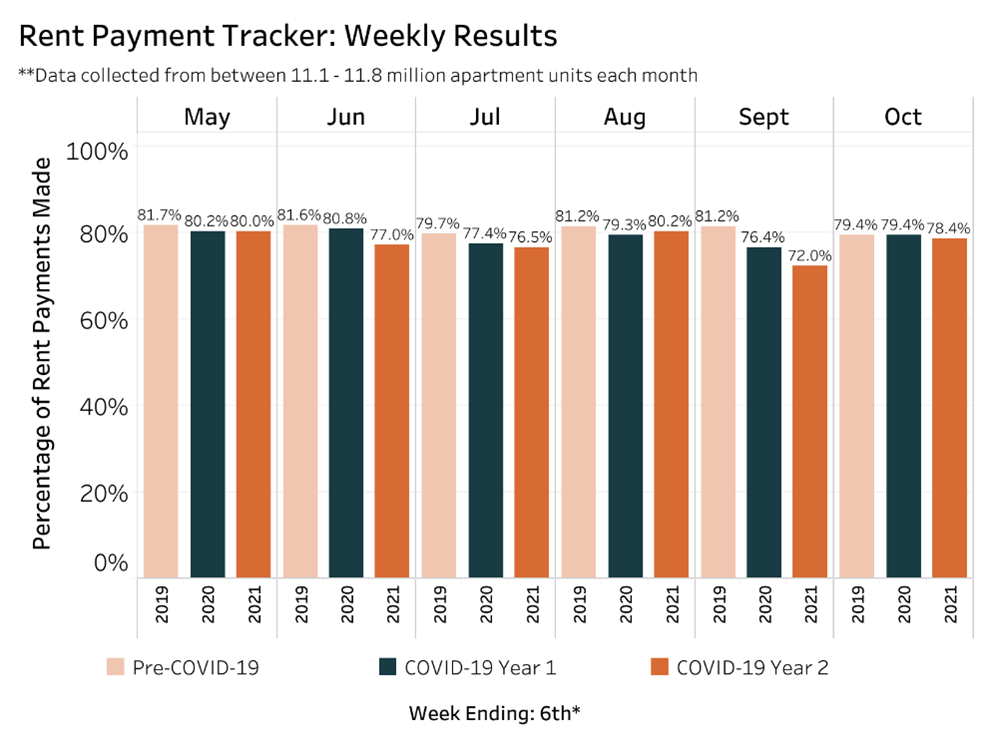

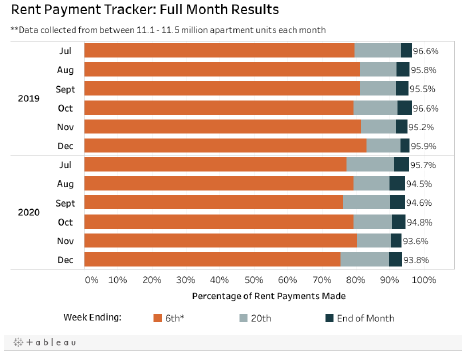

Meanwhile, rent collections post-COVID continue to lag, as the National Multifamily Housing Council found that 78.4% of apartment households made a full or partial rent payment through the first week of October, a one percent decline from the same period in 2020. Los Angeles landlords are owed at least $3 billion in back rent, according to a report co-authored by researchers at UCLA and USC. Across our portfolio, we are still owed significant sums in back rent, and we continue to await payments from the various rental assistance programs. For example, here in California, the State has disbursed less than 20 percent of the $1.4 billion in rental assistance aid that was given to the State by the Federal government, at least at last look.

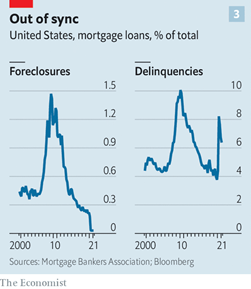

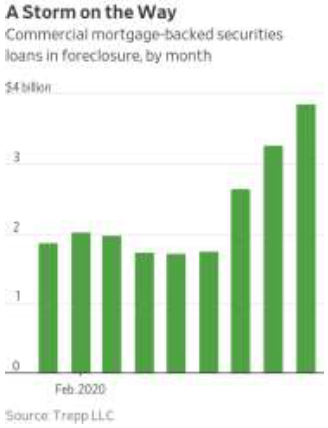

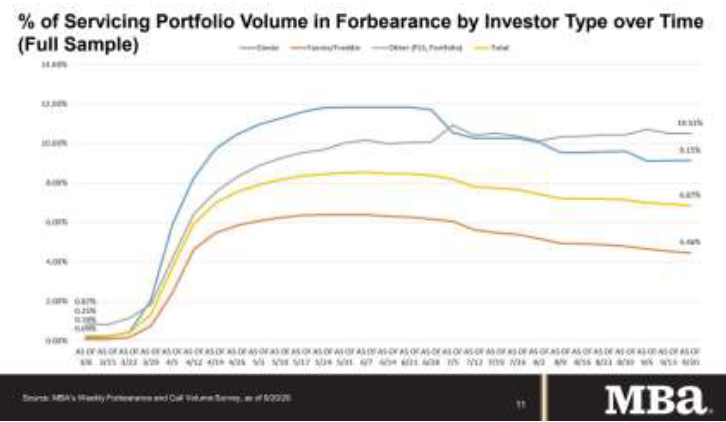

Finally, as eviction moratoriums are lifted, what will the impact be? Will there be a tidal wave of defaults, foreclosures, and evictions? Some 2.8 million households, comprising nearly 7.5 million individuals, are behind in their rent. However, my sense is that a combination of financial aid, rental assistance, and lender/landlord forbearances will stymy any significant increase in foreclosures or evictions, but time will tell.

There is one final topic I thought I would mention briefly before I move onto other subjects. During a recent UCLA Anderson event, I was asked by a former student as to how climate change might impact real estate values looking forward. It is not something I have completely ignored, as I did check predictions about future sea levels when I purchased an income property for my own portfolio down in the Pacific Beach area of San Diego a few years ago.

However, his question made me think more broadly about not just rising sea levels, but about fire risks, and its potential impact on future development and insurance costs, the latter of which is something I have discussed previously. Sure enough, just a few days later, an article appeared in the WSJ about a proposed housing development in Colorado Springs, where we own some assets and are buying others. In this case, a proposed development, a 420-unit project, “2424 Garden of the Gods,” was shelved because of concerns surrounding wildfire evacuations in the area. Similarly, in August, a California appeals court blocked a planned expansion of a resort near Lake Tahoe after agreeing with concerns raised by environmentalists about fire evacuation risks.

Therefore, his question was not only timely, but important. Rising sea levels, in addition to increased levels of drought and associated fire risks, will meaningfully impact real estate. On the one hand, insurance costs are going to continue their upwards march, and in some cases, may be impossible to procure. I bet more than a few of you have received “Notices of Non-Renewal” from your insurance carriers because your property poses “excessive” fire risk. I have. On the other hand, anti-development activists will have another tool in their arsenal, as they argue, in some cases with justification, that certain projects should not be approved because of wildfire risks. Ironically, the decision to mothball the Colorado Springs project may be good news for us, at least marginally, because caps on supply translate to higher rents, all else equal, and we will own three assets in that market by year end.

Higher inflation will persist, at least when it comes to wages, commodities, housing costs, and asset values

As I wrote in one of my recent, more condensed (yes, thankfully), monthly memos, I have always marveled at how Costco has been able to sell a mammoth-sized hot dog and bottomless soda for $1.50, and $4.99 for an entire ready-to-eat roasted chicken, year after year after year. During my last visit a mere three weeks ago, I was profoundly relieved to see that those prices still have not changed. Yet, everywhere else one looks, and I mean virtually everywhere, prices are higher, if not much higher, than they were in the not-too-distant past.

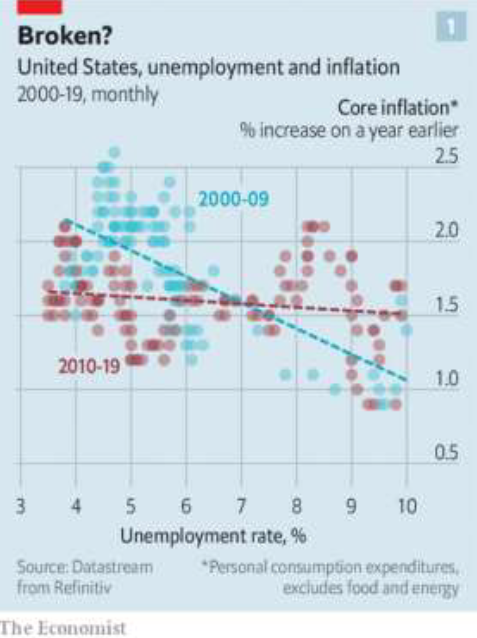

Inflation, as measured by the Bureau of Labor and Statistics, increased 5.2% in August (versus the prior year), excluding food and energy, the third time in the last four months that increases in the consumer price index have exceeded five percent, well above the Fed’s two percent target.

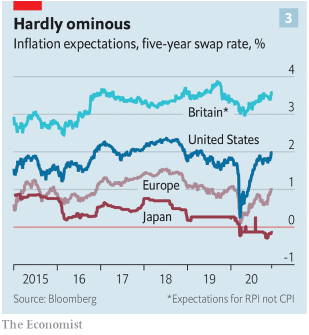

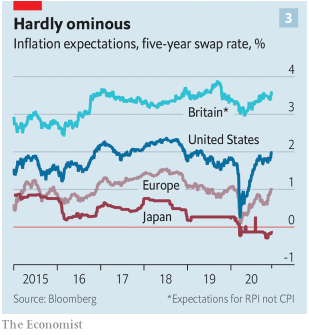

While the Fed has indicated that annual inflation will return to two percent by 2022, that seems like a pipe dream, at least according to investors, who are predicting that the consumer price index will rise by an annual average of 2.64% over the next decade, based on recent pricing in the TIPS (Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities) market:

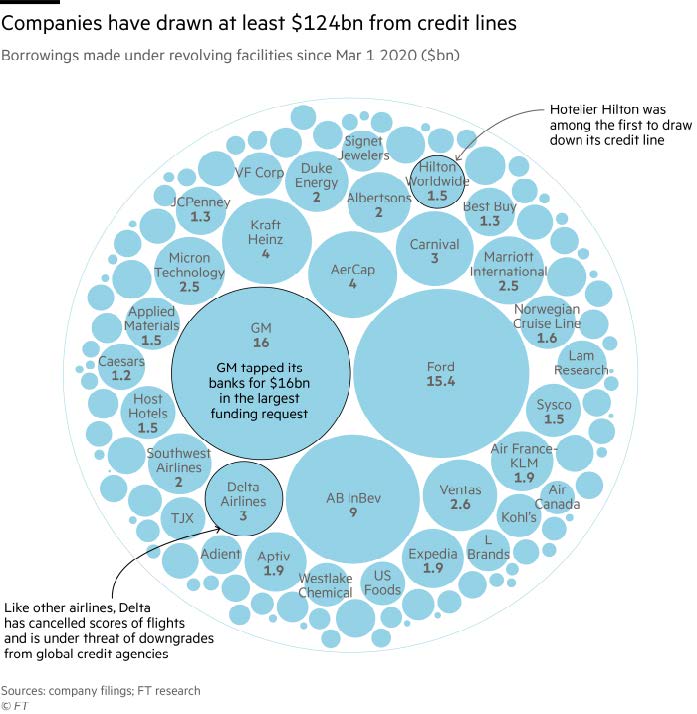

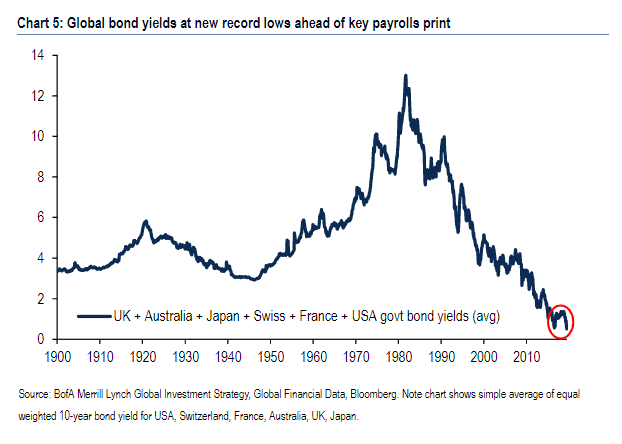

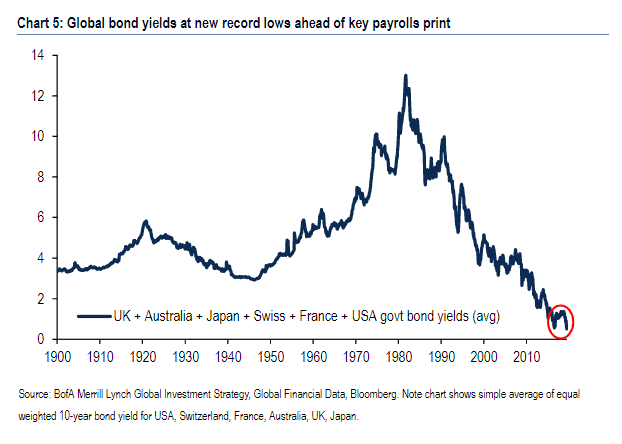

Meanwhile, there is simply too much liquidity on the sidelines for asset prices not to go higher: $20 trillion in M2 money supply and nearly $7 trillion in cash and investments on corporate balance sheets, mostly earning negative real returns. Much of that capital will eventually find its way into the economy and markets, driving real estate and equity markets higher. The impact of the unprecedented largesse of the Federal Reserve, perhaps borne out of economic and COVID necessity, will prove long-lasting, or at least for the next several years, as I see things. Two pictures tell a thousand words.

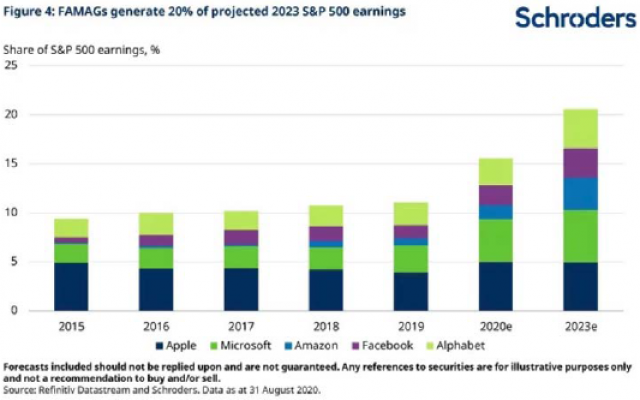

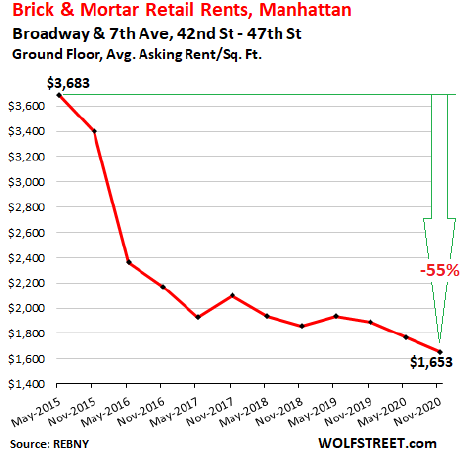

In fact, it can come as no surprise that Google recently announced it was purchasing a Manhattan office building for $2.1 billion, while in 2020, Amazon acquired the nearby former Lord & Taylor department store for nearly $1 billion and Facebook purchased REI’s office campus in Bellevue, Washington for $368 million. Expect more of the same looking forward.

Meanwhile, wages are heading higher, and materially so. Recent labor strikes experienced at John Deere and Kellogg’s are only the beginning, and the principal way to move workers off the sidelines and back into the workforce, is higher wages. In this new reality, Walmart recently increased its minimum wage to $15 across the entire company, and check out this Bank of America advertisement, which appeared in last week’s Los Angeles Times:

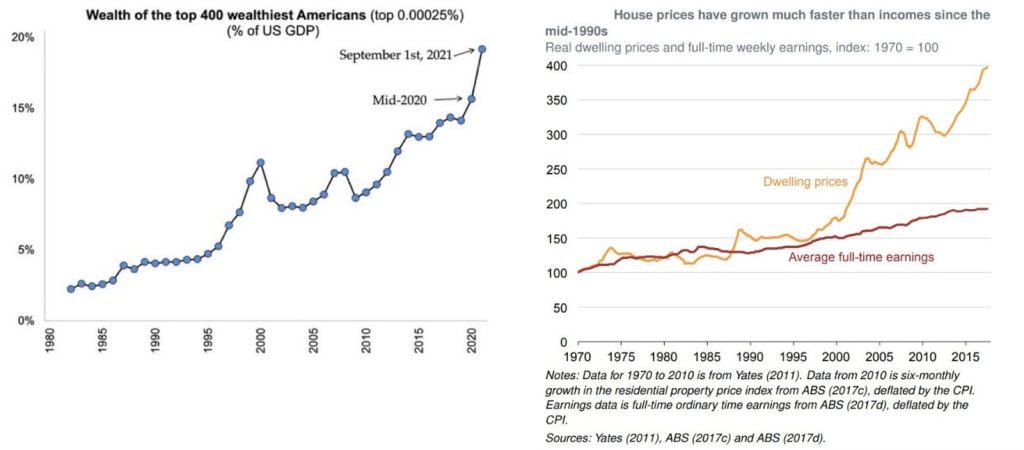

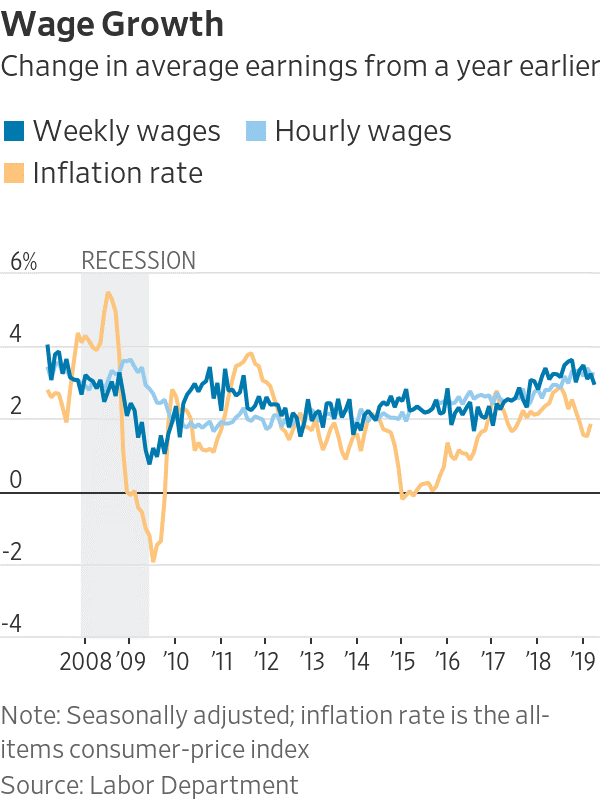

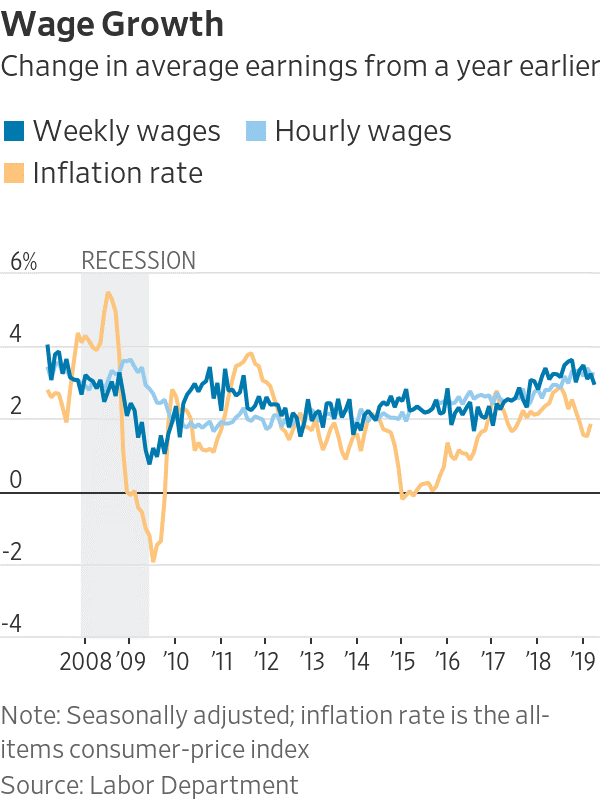

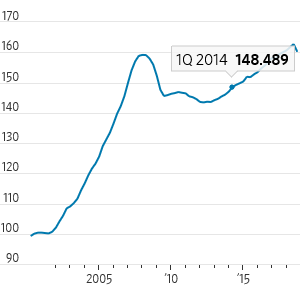

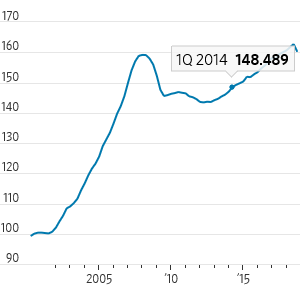

Although perhaps not a universally held view, I have long argued that wages need to be higher, and while I might be biased because higher wages will likely translate to higher residential rents, I believe that the widening gap between the haves and have-nots is economically and socially destabilizing. Since 2010, U.S. home prices have increased by a whopping 153.3%, compared to far more modest wage gains of only 14.2%, essentially matching annual inflation rates (about 1.25% per annum). The chasm between the haves and the have-nots has never been wider. Again, a couple pictures provide meaningful perspective.

Obviously, the biggest concern is that we enter some sort of perverse time machine and head back to the 1970’s, when inflation averaged 6.8% per year. Disco, bell bottom jeans, Studio 54, and hour-long gas lines (my mother’s Dodge Dart, the affectionately nicknamed Red Bomber was a real guzzler) were bad enough, but a return to 1970’s-like inflation would be deleterious, to say the least.

Food prices globally are up 30% this year, and oil prices recently surpassed $80 a barrel, a price last seen seven years ago, almost to the day. And this chart is, perhaps most frightening, apropos of the Halloween season, where slowing growth and inflation become unwanted bedfellows.

While the three A’s (Amazon, automation, and artificial intelligence), low fertility rates, and other demographic shifts provide deflationary counterforces, and all that money supply should keep interest rates low (or lower than they otherwise would be), the excessive liquidity, upward pressure on wages, coupled with supply chain disruptions and pent-up demand, will provide more than worthy inflationary competitors. It’s truly an MMA battle of competing tailwinds and headwinds, and my money is on asset inflation, net-net.

However, if the bond markets are to be believed, the high inflation we have experienced in recent months will, in fact, prove temporal, and I, too, cannot foresee a return to the 1970’s, if just because unions lack the power that they had back then, automation is increasing, and policymakers have thankfully learned a thing or three in the last 50 years. That is not to say that the Fed’s two percent target will not be breached, given the factors we have discussed (e.g., excess liquidity, supply chain challenges) as the TIPS market is already predicting somewhat higher inflation, but even if that 2.64% annual inflation comes to pass over the next decade, it should not be worrisome. Stay tuned.

The Fed is walking a very precarious tightrope, as it tries to thread an economic needle

Taper and raise interest rates too quickly, and the Fed risks pushing the economy into recession and economic stagnation. Continue their $120 billion a month bond-buying spree and a near-zero interest rate policies, and they risk adding more fuel to the inflation fire, if not asset bubbles, something we are already witnessing in several corners of the markets. Exhibit A might be this past weekend’s headline from the WSJ: “Trump SPAC Swept Up in GameStop-like Frenzy.” Buying frenzies in everything from cryptocurrencies (yes, Bitcoin has raced to record highs recently) to certain SPACS (check out “DWAC,” the stock symbol for the new Trump social media SPAC) to single-family-homes makes me inherently uneasy. And as I have discussed at length previously, the Fed’s Balance Sheet has already experienced unprecedented expansion in recent years.

My sense is that the Fed is going to maintain the status quo for now, until there is clearer economic direction. As I mentioned, the bond markets don’t seem spooked by the specter of higher inflation or interest rates, and rates remain low, even with 10-year Treasury yields now trading at about 1.60% (versus 0.97% at the end of 2020).

In recent Congressional testimony, Fed Chair, Jerome Powell agreed that “we are seeing upward pressure on prices, particularly due to supply bottlenecks in some sectors,” and stated that “these effects have been larger and longer-lasting than anticipated, but they will abate, and as they do, inflation is expected to drop back toward our longer-run two-percent goal.” His subsequent commentary was fairly generic, as he ambiguously stated that the Fed will respond to “market shifts,” whatever that means. We will just need to stay tuned, and we will.

Supply chain bottlenecks, resulting in dozens of ships anchored off our coasts awaiting delivery of goods and empty store shelves, will clear in time, but how long that takes is unclear

It is not merely a shortage of truckers, labor shortages generally, or new environmental regulations causing our supply chain bottlenecks, though they are certainly significant contributing factors. Frankly, COVID-19 and the economic dislocations it caused revealed longstanding risks and vulnerabilities of interconnected and geographically concentrated global supply chains. While the bottleneck should clear in the coming months, policy makers and businesspeople alike will need to rethink supply chains and how they procure goods and services to prevent future disruptions. The primary beneficiary in the real estate market will be industrial assets, which will benefit from the onshoring of previously outsourced goods.

Because the real estate sector accounts for such a significant part of China’s economy (20 to 25% of GDP, versus 15 to 18% here in the U.S.), China cannot afford widespread failures in the sector for fear of the resulting fallout

While Evergrande and its compatriots (e.g., Sinic Holdings and R&F Properties) are clearly over-leveraged ($2.8 trillion in debt, collectively), the Chinese government will likely bail them out in some way, shape, or form, having learned the lessons from Lehman Brothers’ collapse and the subsequent financial crisis. Perhaps we should think of the real estate tightrope China must deal with as analogous to the challenging balancing act our Fed must perform. I just don’t see China allowing a wave of developer defaults, and in fact, late last week, Evergrande made some outstanding and past-due interest payments.

But that is not to say it will be easy or painless. In fact, just last week, China disclosed that its third quarter growth in GDP was 4.9%, which hardly sounds unhealthy, but it compares quite unfavorably to 2020’s third quarter growth of 7.9% and higher analyst forecasts. With countless construction projects now being halted, China’s GDP data may be even more sobering in coming quarters. However, I don’t anticipate that China’s real estate challenges will spread to our shores in any meaningful way.

Remote work, or some sort of hybrid-work model, will persist, allowing some workers to live remotely indefinitely, with long-lasting impact on secondary and tertiary real estate markets and their suburbs

Just before the second quarter ended, Price Waterhouse announced that none of its 40,000 workers need return to the office, adding to the dozens of others companies that have made similar announcements (e.g., Adobe, Capital One, Coinbase, Dropbox), at least for a portion of their employees. As a result, the demographic shift we have seen over the last decade, with significant numbers of households relocating from urban cores to suburban secondary, tertiary, and quaternary markets will persist.

In fact, I recently learned a new word, “Exurb,” referring to suburbs of suburbs, which have experienced significant growth in recent quarters, in part due to the trend of relocating workers. Areas outside of Denver, Salt Lake City, Phoenix, Charlotte, or Nashville represent these new and growing exurbs. The shift to remote work will provide additional tailwinds to these markets, and Clear Capital’s strategy and acquisitions of assets in these markets is no accident.

Political paralysis will persist, minimizing the likelihood that meaningful legislative changes to public policy, spending, or taxes that might impact real estate markets are significantly reduced

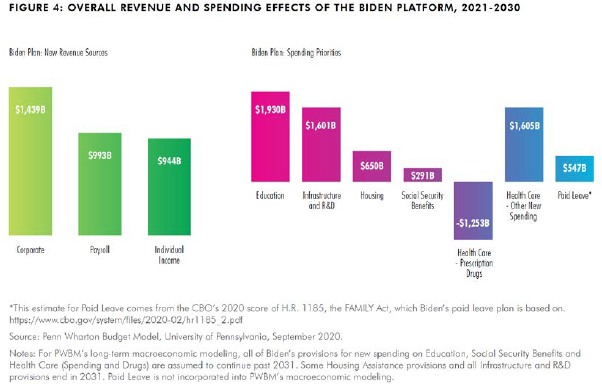

A question I am frequently asked is what is likely to happen to tax rules surrounding 1031 transactions, in which gains realized from the sale of investment property can be deferred, so long as the sales proceeds are reinvested in another investment property (or properties) in a timely manner. You may recall that President Biden has on more than one occasion indicated that this provision of the tax code ought to go the way of the dodo bird. Well, I think we should rest easy. While the current version of Biden’s tax reform bill does cap 1031 transactions at $500,000, I see little, if any, chance that the legislation will be passed.

After all, the Administration is still focusing on the stalled $3.5 trillion infrastructure legislation, which has now been reduced to less than $2 trillion, and any vote on that legislation still seems out of view. The parties themselves can’t seem to agree on much, with political infighting providing meaningful legislative impediments, with numerous old-timers being “eliminated” in quasi-Squid Game style, as they decide not to run for reelection or lose primary battles. On a more local level, politicians will continue to address housing affordability and homelessness with their typical incompetence and myopia.

During the quarter, California Governor Gavin Newsom, having survived the recall effort, signed into law Senate Bills 9 and 10, which eliminates R-1 zoning, and allows for up to four units to be built on lots previously restricted to single-family dwellings. While perhaps a step in the right direction, the impact will prove marginal, likely adding less than half a million new rental units. The new law does nothing to address other impediments to new construction, from higher building costs, labor shortages, and the need for local officials to approve projects more expeditiously. For example, when Los Angeles passed an ordinance allowing detached garages to be converted to dwellings (Additional Dwelling Units or “ADUs”), the ordinance required that the city approve qualifying projects within 30 days. Well, approvals are now taking more than six months. Color me shocked.

Finally, there are two other public policy related tidbits I thought I would mention, one from across the pond, in Berlin, which you may recall enacted the most restrictive rent control policies I have ever encountered and described previously. Well, in late September Berlin’s voters decided to expropriate apartments from any landlord which owns more than 3,000 units in the city, a move akin to eminent domain. The referendum is not legally binding, so the next move belongs to city officials, which would need to acquire the properties from these landlords, requiring some 40 billion euros. Where it would find this sort of funding is beyond my knowledge. Perhaps it should just issue its own cryptocurrency and purchase the assets with a new “Berliner Coin.” Sarcasm aside, I don’t believe that the city will expropriate anything meaningful, but it speaks to just how deep divisions are between landlords and tenants in certain housing constrained markets, and radical maneuvers being considered to address them.

Lastly, I came across a story in the Los Angeles Times a couple of week ago, describing how a local judge struck down a previously approved 1,119 residential housing project in San Diego County (Otay Ranch), which would have included commercial stores, a new school, and a fire station. The project was consistent with zoning regulations, had been approved by the County Board of Supervisors, and was supported by local fire officials. However, the development was opposed by the Sierra Club and a group of other environmental groups, who raised concerns that the project did not do enough to address affordability issues, wildfire risks, greenhouse gases, and the potential impact on the endangered “Quino checkerspot butterfly.” Without commenting on the case specifics, the story reflects why housing supply cannot possibly keep up with demand…and won’t, in California, or just about anywhere else.

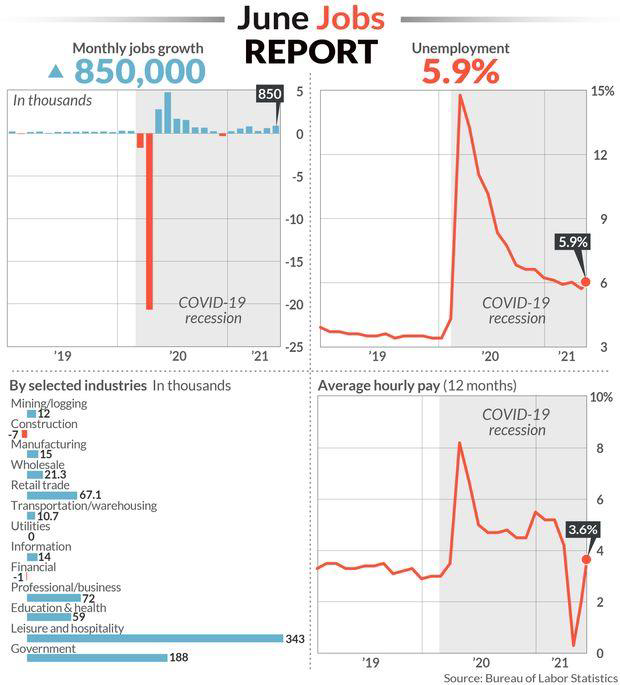

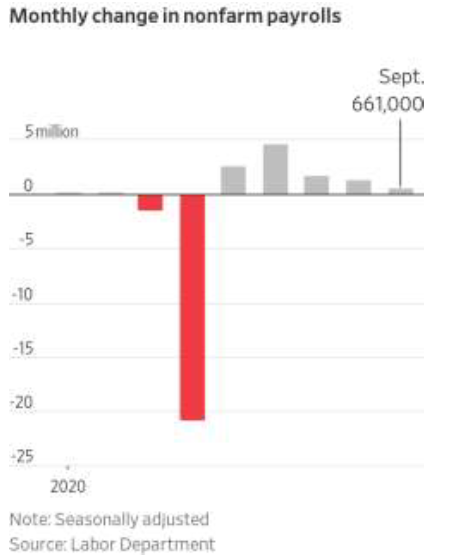

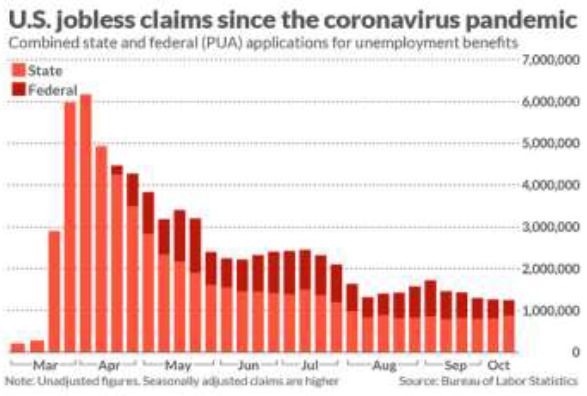

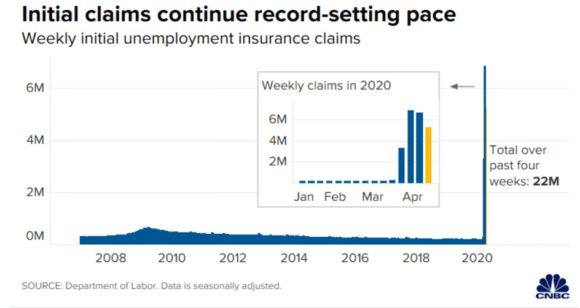

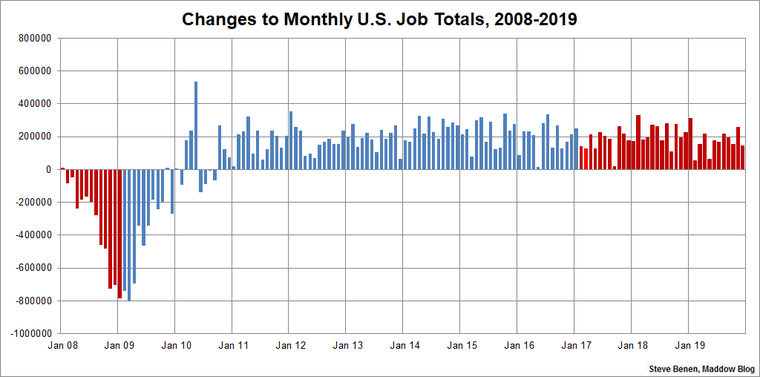

Where have all the workers gone and when will they return to participate in the labor force?

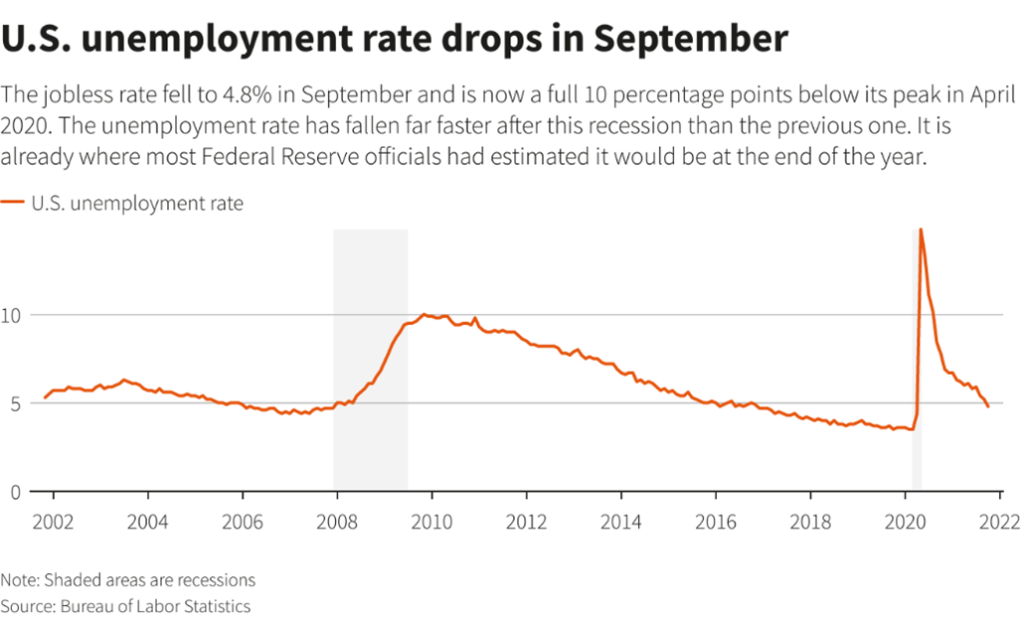

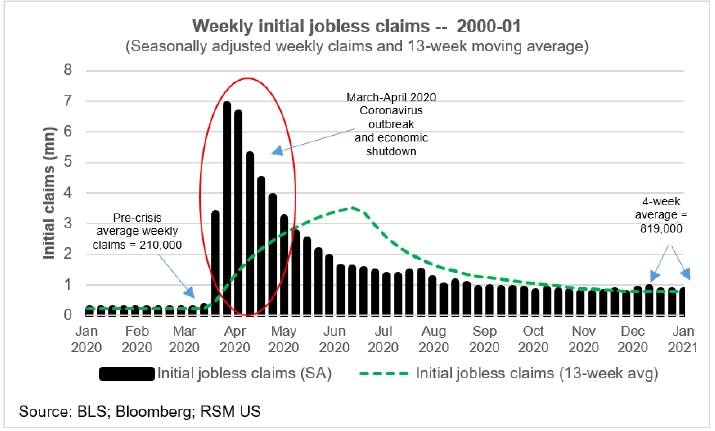

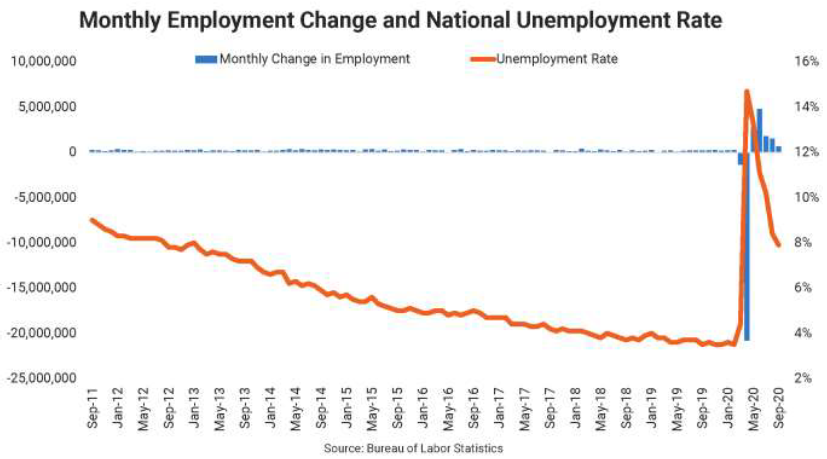

While the overall unemployment rate dropped in September, to 4.8%, some ten percent below where it was in April 2020, when some 23 million people were unemployed immediately following the COVID outbreak, we are experiencing near record-low rates of labor participation during an economic recovery. Is this going to be the latest installment in the Hardy Boys series, “The Mystery of the Missing Worker?” Well, according to the Department of Labor, there were nearly 11 million job openings at the end of July (seasonally adjusted), or 1.3 jobs for every person considered unemployed, records for both metrics, so perhaps the Hardy Boys could indeed have a meaningful mystery on their hands.

Is it really all about unemployment benefits, as some would have us believe? No. While certainly impactful, the labor shortage is multifactorial, as I have discussed previously, and we should all avoid simple singular narratives trying to explain complex topics like the labor shortage. Sure, enhanced federal and other unemployment benefits and government-sponsored assistance programs were impactful, but the causes are numerous, from a lack of childcare, lingering concerns over the virus, a reduced worker base in urban cores, increased automation, inadequate wages, and/or retiring Baby Boomers (and others, perhaps). Some may simply be fighting employee mask mandates or trading various cryptocurrencies.

In fact, the labor force shrunk in September, for the first time since May, indicating that lots of folks seem content with sitting on the sidelines. Despite record job openings, employers only added 194,000 jobs in September, below expectations for the second consecutive month. In August, the economy added just 235,000 jobs, less than a third of the 720,000 that was anticipated.

Finally, real estate developers are on the front lines of the labor shortage. In a recent poll conducted by the National Multifamily Housing Council, 50% of respondents said they had been impacted by the lack of available labor. Thus, contractors and real estate developers are being hit with multiple whammies, a shortage of labor and materials, along with higher prices for both.

And, as always, here are a few other tidbits I found newsworthy from the third quarter

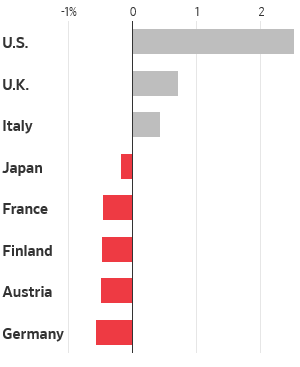

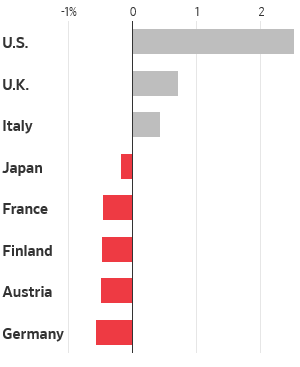

- The 2020 Census data is out. Initial details from the 2020 Census were released in August, revealing a few noteworthy data points. One is our increasing diversity, as our non-Hispanic, white population declined 2.6% over the last decade, while the country’s total population grew only 7.4% during the decade, the second slowest on record, second only to the 1930’s, the period of the Great Depression. Meantime, the under-18 population decreased, by 1.4%. I find our slowing and aging population growth to be concerning, as it will translate to slower economic growth and deflation. We do not want to repeat the mistakes of our Japanese friends, who have suffered with the consequences of unfavorable demographics – slow population growth and an aging populace – for decades.

- The corporate diaspora continues. Over the last few years, I have written extensively about population moves away from the coasts. Frankly, this reality has driven much of Clear Capital’s acquisition strategy, as we pursue opportunities in the Southwest, Northwest, and Mountain West regions of the country. However, the population shift is both a cause and effect of corporate migration, which has also been occurring, as large, multinational companies relocate from the coasts to less expensive locales. In mid-August, AECOM, the large infrastructure, construction management, and engineering firm with deep and long-standing roots in Southern California announced that it is relocating its headquarters to Dallas. About three weeks ago, Tesla officially announced that its new headquarters will be in Austin, a move from Fremont, in Northern California. These two companies are now part of a fraternity that includes Hilton, Northrop Grumman, Occidental Petroleum, Nestle, Toyota, CBRE, and hundreds of other companies who have relocated over the last decade or so.

- Household debt continues to soar. U.S. household debt soared to nearly $15 trillion in the second quarter, increasing by $313 billion (2.1%), the largest nominal jump since 2007. Mortgage balances – the largest component of household debt – rose by $282 billion, while auto loans, credit card balances, and student loans increased by $33 billion, $17 billion, and $14 billion, respectively. Mortgage originations (including refinancing of existing mortgages) reached $1.2 trillion, surpassing volumes in the preceding three quarters combined. The data is likely skewed by COVID and pent-up demand, but low rates, an improving economy, higher asset prices, and all that liquidity are impacting household borrowing and leverage. While I do not see excesses or the sort of reckless lender behavior witnessed before the last financial crisis, I am watching the data carefully. We all should.

In closing, it has been a newsworthy quarter, such that the Summer Olympics and Afghanistan withdrawal debacle seem eons away, like distant memories. Many challenging questions remain, and I don’t think even a consortium of Sherlock Holmes, the Hardy Boys, and the Psychic Friends Network can provide definitive answers as to what lies ahead. Regardless, I remain convinced that higher asset prices, longer-lasting inflation, higher wages, and anemic economic growth will characterize the remainder of this year and next, while politicians continue to spend more time talking to news outlets and any microphone in front of them than legislating in any meaningful way. Let’s hope I am wrong in a few of my predictions.

As always, I would like to express my sincere appreciation and thanks to you, our investors, supporters, and friends as well as the entire Clear Capital and Clarion Management teams for their extraordinary efforts over a challenging period. I remain grateful and feel very fortunate to work alongside such a talented and dedicated group of individuals.

With that being said, I would be terribly remiss if I did not end this missive by acknowledging the loss of one of our own, Clear Capital’s very first employee, Dan Lukes, Director of Asset Management, who passed away from COVID last month. Dan’s contributions to the firm were immeasurable, and he will be profoundly missed, personally and professionally. Our sincere and heartfelt condolences go out to his colleagues, friends, and family members. May his memory be a blessing.

Best,

Eric Sussman

“Inflation is when you pay fifteen dollars for the ten-dollar haircut you used to get for five dollars when you had hair.”

– Sam Ewing“Money can’t buy you happiness, but it does bring you a more pleasant form of misery.”

– Spike Milligan

As I watched Richard Branson, the eccentric billionaire and founder of the Virgin Group, rocket to the edge of space last weekend, I felt profoundly mixed emotions. On the one hand, I marveled at the achievement that the first suborbital passenger flight to space represents, and human ingenuity, generally. Although I have absolutely zero interest in traveling to Mars (just getting to the office in Los Angeles traffic or fighting for a parking space at Costco are exciting enough) or starting an interplanetary real estate fund (not yet, but stay tuned!), the launch was thrilling to witness. Perhaps the flight was not quite as dramatic or significant as Apollo 11’s historic moon landing, but it certainly represents a significant milestone.

At the same time, however, Mr. Branson’s flight reminded me of the significant challenges we face back here on planet earth, and whether the billions being spent on these space-seeking endeavors by Branson and his billionaire brethren, Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos, could help address problems we face closer to home: increasing wealth inequality, a lack of affordable housing and homelessness, the private sector’s encroachment on and need to assume what were previously public sector responsibilities, the challenges businesses are facing to fill job openings, concerns about inflation, the lingering impact of the pandemic including a recent resurgence in cases and hospitalizations, and record heat waves and drought in some parts of the world and record flooding in others. And to think I did not even mention the toxic political environment, the tragic collapse of the Surfside condominium complex, or Brittany Spears’ conservatorship troubles.

I suppose it is a question of perspective as some of these realities present opportunities for Clear Capital and investors generally, who benefit from higher real estate values, rents, and stock prices, fueled in part by the impact these challenges create: a material undersupply of housing (both single- and multifamily), persistently low interest rates, and record levels of liquidity and household wealth. While we continue to face challenges with regards to rental collections, the lingering effects of the pandemic (past due rents across our self-managed assets exceed $4 million), and the uneven economic recovery, operating metrics (e.g., economic occupancies, rental rates) across our portfolio have improved substantially in recent months.

Thus, despite so many broad social, political, and economic challenges, the underlying fundamentals and outlook for Clear Capital and housing markets is very positive. As a result, we remain optimistic as we look out to the remainder of 2021 and beyond. Perhaps not surprisingly, we have been very busy of late, having acquired the following four assets (461 units) since my last update:

- Urban Park (Aspire Midtown), 104 units, Phoenix, Arizona

- Mountain View (Aspire West Valley), 96 units, West Valley City, Utah

- The Preserve (Aspire Oregon City), 135 units, Oregon City, Oregon

- Landing Point (Aspire Salt Lake City), 126 units, Salt Lake City, Utah

We anticipate presenting you with additional offerings shortly and hope one or more might interest you. I imagine we will also entertain offers to sell some assets, especially those where we have implemented our value-add strategy, captured higher rents, and can take advantage of favorable market conditions. With all this being said, highlights and relevant tidbits from the second quarter are as follows:

- Housing prices continue to skyrocket, while apartment rents have mostly recovered from pandemic-related declines (and then some), at least in most markets.

Perhaps the most common question I am asked is: “Are we in another real estate bubble?” The short answer is “no,” though it is easy to think so given recent headlines and countless tales about “all-cash, non-contingent offers above asking prices” for single-family homes in markets from Boise (ID) to Bethlehem (PA), to Tulsa (OK) to any Rust Belt City near you. Some buyers are acquiring homes, sight unseen, relying solely on video tours.

Anywhere one looks, data points confirm that we are in a strong bull market when it comes to housing prices. According to Zillow, the price of a single-family home in the U.S. increased approximately 15% during the past year (through June), with the median price nationally rising 24%, to over $370,000.

However, as much as significantly higher single-family home prices bring back memories of the period preceding the Great Recession, this time is indeed different, at least as I see it. Bank balance sheets are in far better shape, lending standards have not been materially relaxed, and average credit scores of borrowers are higher. Historically low interest rates, record levels of liquidity, anachronistic zoning regulations, institutional buyers (according to the WSJ, 20% of homebuyers are investors, including Blackstone, which reentered the single-family rental business after previously exiting it), a lack of buildable lots, higher commodity prices, and pent-up demand provide substantial market tailwinds.

And as sobering as it might be, many of these drivers of higher housing prices will persist indefinitely, such that lower single-family home prices are not likely anytime soon, as I have discussed in detail in prior newsletters and my podcast (“Focus on Facts”) several months ago. Meanwhile, a sampling of recent headlines captures the market sentiment surrounding home prices, and I could have cited dozens and dozens more, from nearly any news outlet or newspaper:

“The Housing Market is on Fire,” Bloomberg Business Week (June 14)

“Real Estate Frenzy Hits Small Towns,” Wall St. Journal (May 20)

“The East Bay Real Estate Market is So Hot, Housing are Selling for More than $1M over Asking Price,” SFGATE (May 5)

“Austin housing market sets new record as median home price hits $575,000,” Culture Map Austin (July 16)

“Long Island Home Prices Hit Record High Due to Insatiable Demand,” Newsday (July 15)

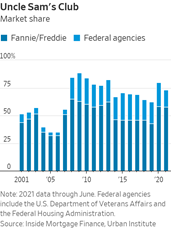

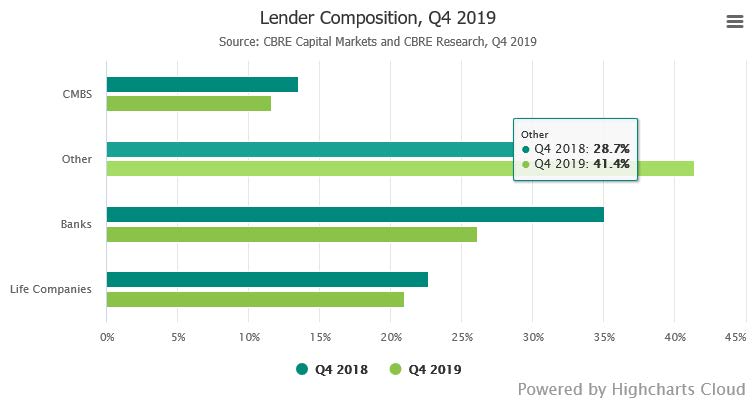

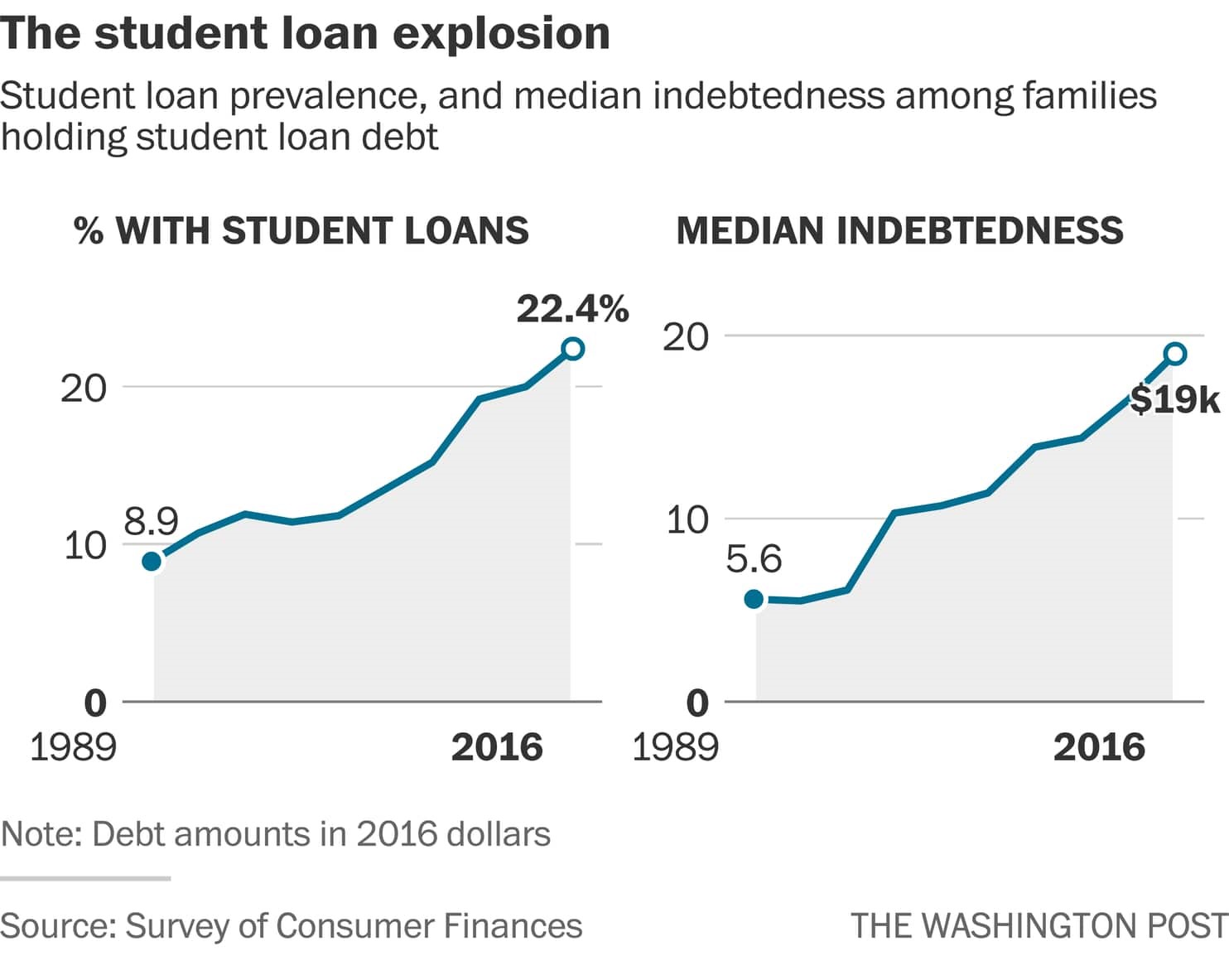

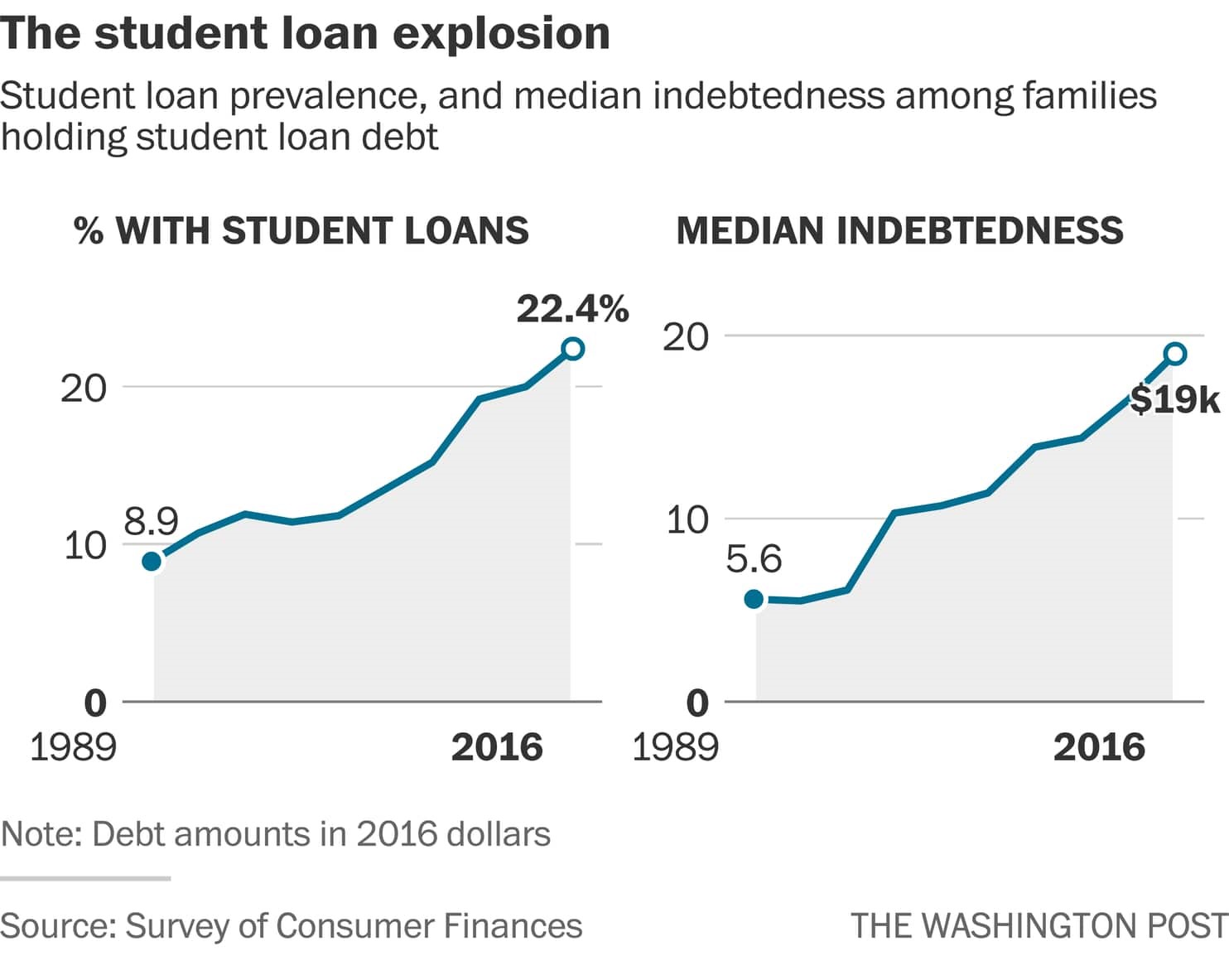

As if demand were not already strong enough, the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) recently announced that it is changing how it factors in student debt when assessing a prospective homebuyers’ creditworthiness and eligibility to qualify for FHA assistance. Clearly the change is intended to allow more borrowers to qualify for loans backed by the FHA, namely that superhero duo, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. The change will result in lower debt-to-income ratios for prospective borrowers with student loans, increasing the eligibility of certain prospective homebuyers for FHA-based loans. Perhaps increased competition from large debt funds and life insurance companies for some of FHA’s customers are compelling the change. Regardless, the competition and tremendous liquidity are compressing spreads, reducing borrowing rates, and increasing demand just as one would predict, although I am not sure the market needs any more demand drivers.

However, even if demand were to soften due to an economic downturn or increases in interest rates, neither of which I foresee, a systemic and persistent shortfall in supply remains the real culprit, as I have described previously, and I cannot foresee how that reality will reverse course anytime soon. The current supply of homes for sale represents less than 2.5 months of inventory versus 3.6 months one typically sees at historic cycle peaks. In many “hot” markets in the Southeast and Southwest, less than one month’s inventory is currently available. Earlier this month, Bank of America estimated that only 65,000 “starter homes” were completed in 2020, less than a fifth of what is typically built.

Sure enough, a new National Association of Realtors study reported that construction of new housing during the past 20 years fell 5.5 million units short of longer-term needs, requiring a “once-in-a-generation response.” Unfortunately, however emphatic their urging, it will go unheeded, but not because of a failure to acknowledge or recognize the problem. Political paralysis and the complete inability of competing factions to compromise and appreciate the most basic of principles, pitched back in the 18th century by the British philosopher, Jeremy Bentham, that the true measure of any “right” policy is that which provides the “greatest good to the greatest number” remain the culprits.

I even read that the U.S. is short of homebuilders themselves, which may, in part, also help explain the chronic undersupply of new housing. In 2007, the Census Bureau indicated that there were over 32,000 “spec” builders in the U.S. And today? Less than half that figure. There has certainly been some consolidation in the industry, while large, publicly traded homebuilders (e.g., D.R. Horton, Lennar, PulteGroup) have significant, if not insurmountable, scale and cost advantages over local or regional players.

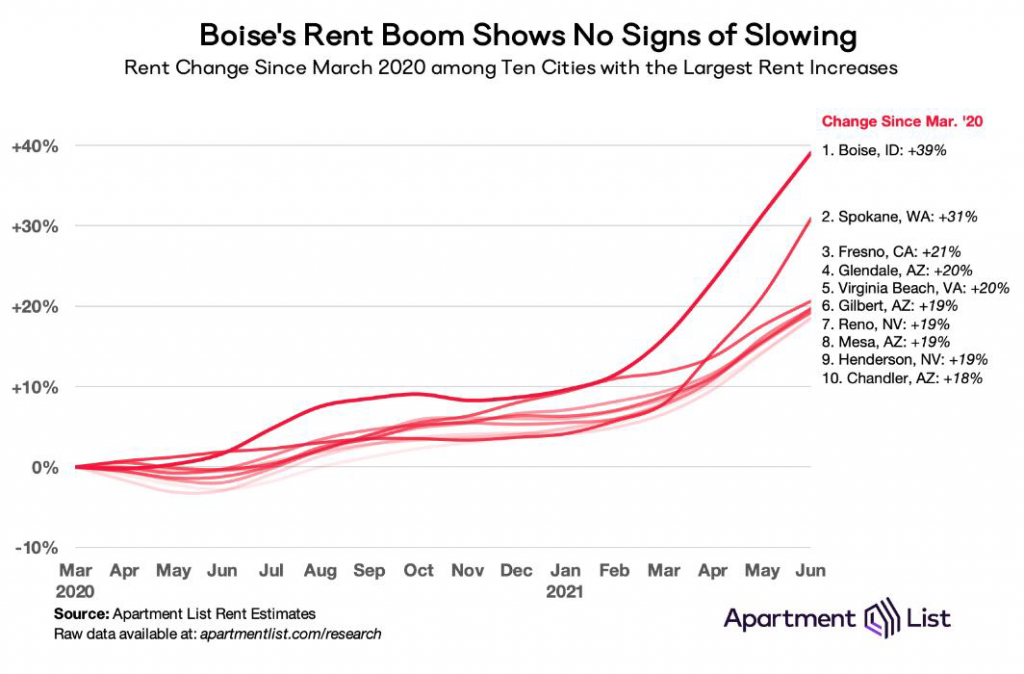

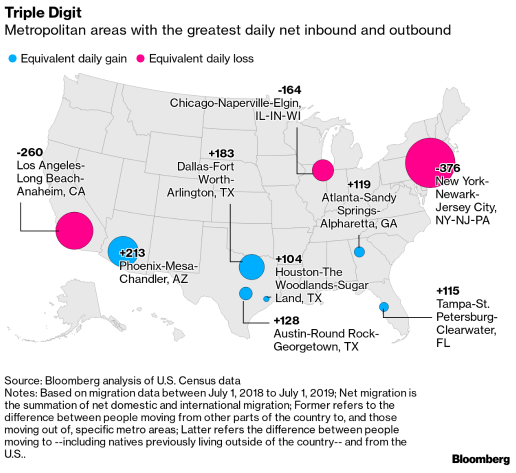

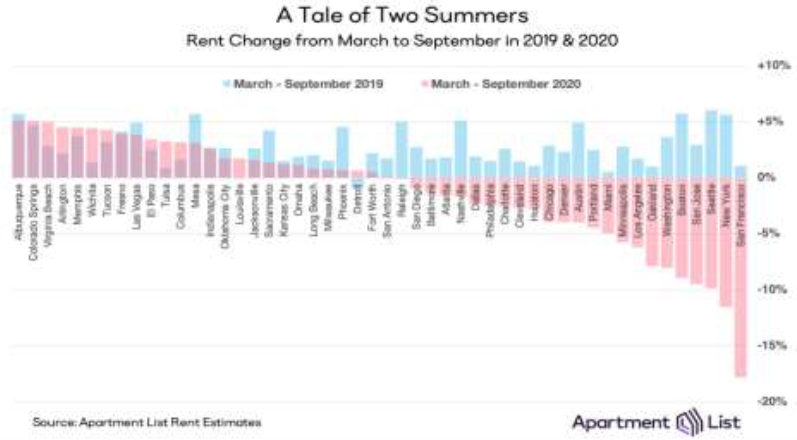

Meanwhile, rents have continued to recover from their pandemic swoon. Nationally, apartment rents increased 2.3% in June and are up 9.2% for the year. In 38 of the largest 50 metros, rents hit new peaks during the quarter. One pattern arising during the pandemic perpetuated, as suburbs led in rental growth. Among the markets that witnessed rent increases of more than 15% during the quarter include Riverside (CA), Memphis (TN), Tampa (FL), Phoenix (AZ) and Sacramento (CA). Even rents for single-family homes were up sharply during the quarter, up over 5% year-over year.

Moreover, the number of occupied apartments in the largest 150 metros increased by nearly 220,000 units in the quarter, the largest quarterly increase since the early 1990’s when such data was first tracked. Here, markets in the Sunbelt and previously hard-hit urban coastal markets led the way. However, national figures mask significant regional variations, as many markets, mainly coastal, continue to see rents well below pre-pandemic levels. For example, rents in San Francisco and New York City remain nearly 15% lower than those witnessed in March 2020, though they have rebounded sharply, up 17%, since the start of the year.

Perhaps the biggest challenge remains collections, or differences between physical and economic occupancies. However, while tenants continue to struggle to pay rent on time, before the end of the first week of any given month, they are mostly paying and meeting obligations.

- Secondary, tertiary, and quaternary single- and multifamily markets continue to outpace coastal competition.

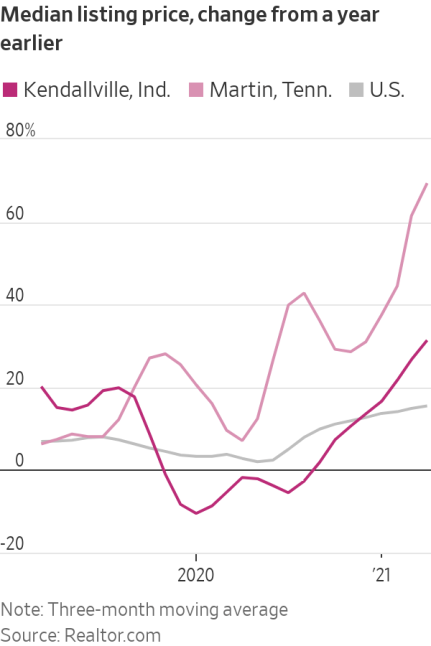

You may recall that I mentioned that the “hottest” single-family real estate market during the first quarter of 2021 was Fresno, California, according to the Wall Street Journal. However, I may need to offer a mea culpa because I subsequently read articles elsewhere that claimed the hottest market might have been either C’ouer D’Alene (ID); Glendale, (AZ); or, Kendallville, (IN), depending on the news source.

Perhaps we are merely splitting hairs and getting lost in the trees, while missing the forest, that the market leaders – whether Fresno, C’ouer D’Alene, or Glendale – are an unlikely bunch of tertiary markets, not nearly primary or coastal. Even Harry Potter and his wizardry would find affordable housing in Hogwarts hard to find. I am not sure Clear Capital will be pursuing opportunities in any of these markets, especially Hogwarts, though the graph below indicates that perhaps we should, if the multifamily fundamentals and price changes in these same markets are like those impacting single-family home prices.

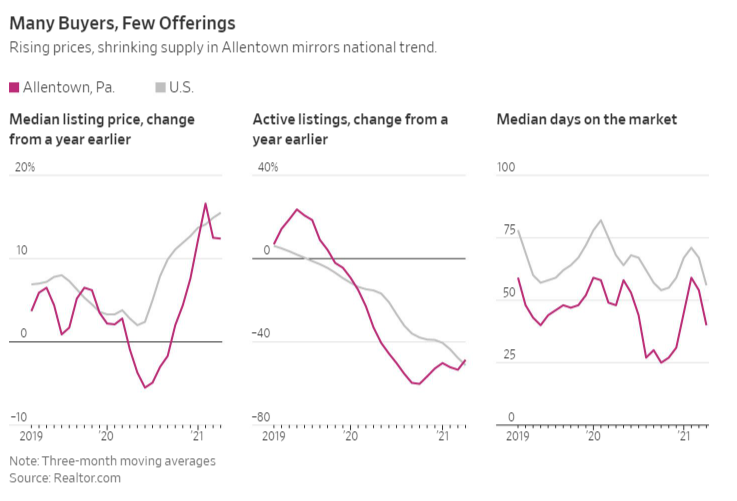

Perhaps a different view, data from Allentown (PA), where they may have “closed all the factories down,” according to Billy Joel, indicates that even that particular market has not experienced tempered housing demand, at least recently.

The story is precisely the same in the multifamily market, as alluded to above and discussed in previous quarterly memos, and precisely why Clear Capital continues to pursue opportunities in markets like Colorado Springs, Salt Lake City, and Phoenix. Pictures do indeed tell a thousand words.

- While concerns about inflation remain widespread and the topic of countless news articles, the bond market is telling us such worries are overblown.

It is truly remarkable how the focus of reporters can change on a dime (or perhaps a quarter these days?). For years, I saw few articles that raised the specter of higher inflation, even as the Federal Reserve was printing money at record rates and asset prices continued to grow. And now? Nary a day goes by without one economist or another raising the prospect of systemically higher inflation.

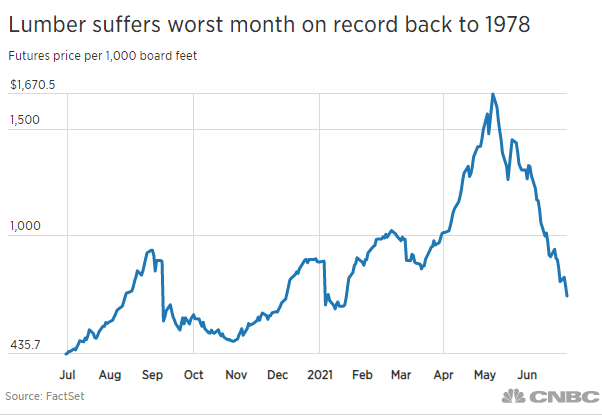

It is really no wonder, as just last week the Labor Department reported that the Consumer Price Index rose 0.9% in June, the largest monthly increase since June 2008, and increased 5.4% over the last twelve months. Core inflation, which strips out volatile food and energy prices, rose 4.5%, the largest increase in that measure since September 1991. Everywhere one looks, whether it is your local Chevron, Home Depot, or Chipotle, higher prices are on the menu (the menus at Chevron and Home Depot might be worth avoiding).

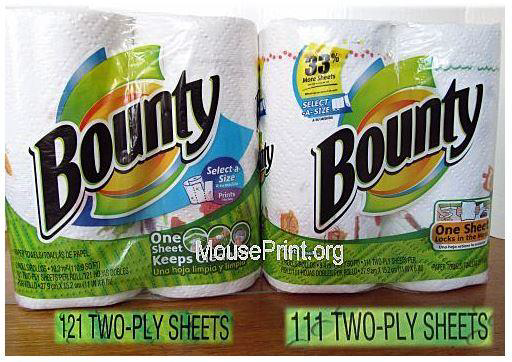

And if companies are not increasing prices, they are accomplishing the same objective by shrinking the sizes of their products, something NPR creatively called “shrinkflation.” For example, Bounty may be the “quicker-picker-upper,” but it recently has been a “quicker-paper-shrinker,” reducing its package sizes by nearly ten percent.

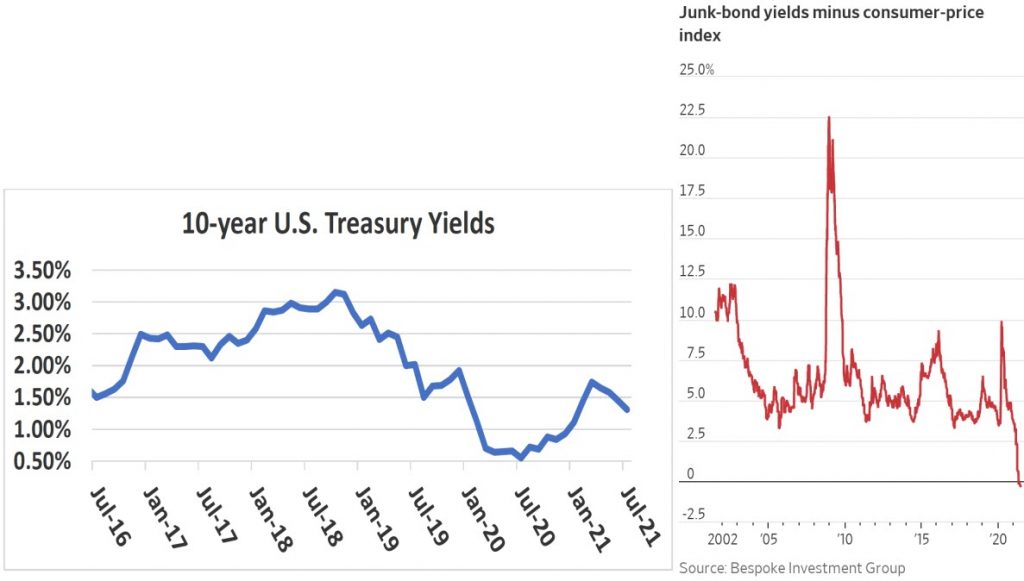

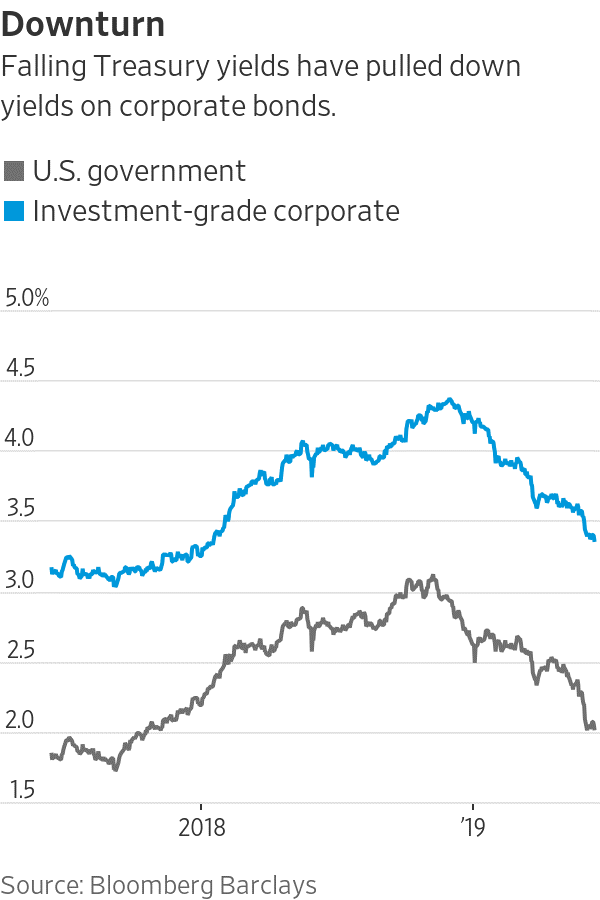

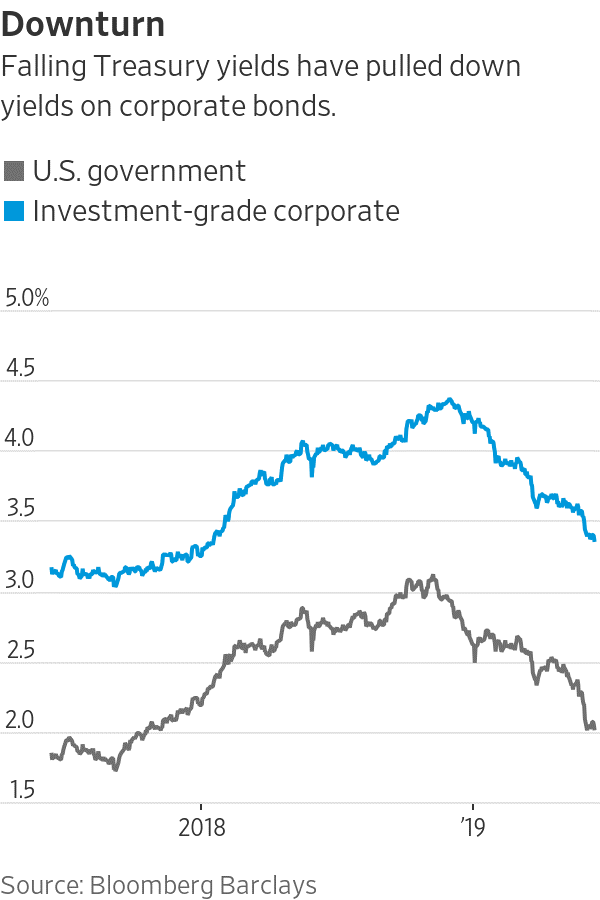

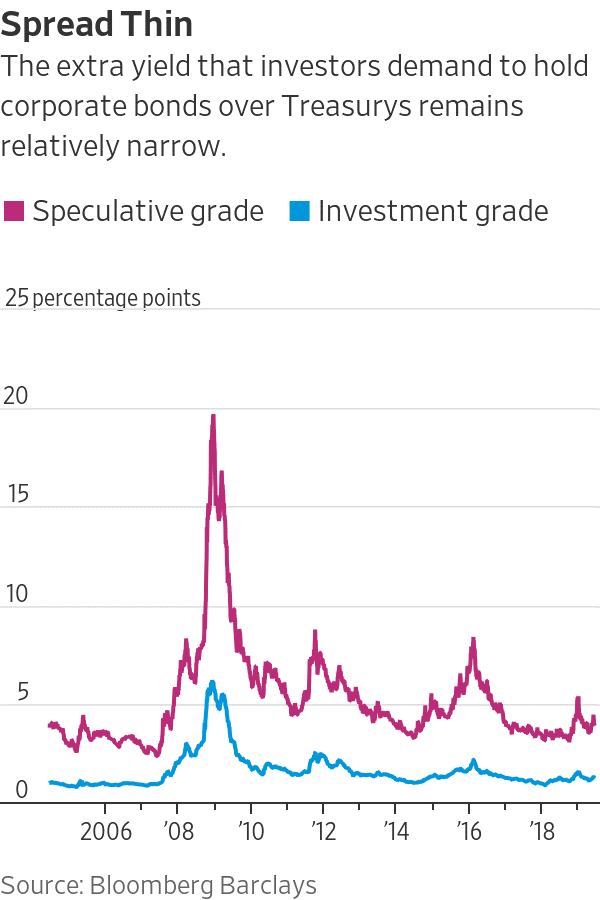

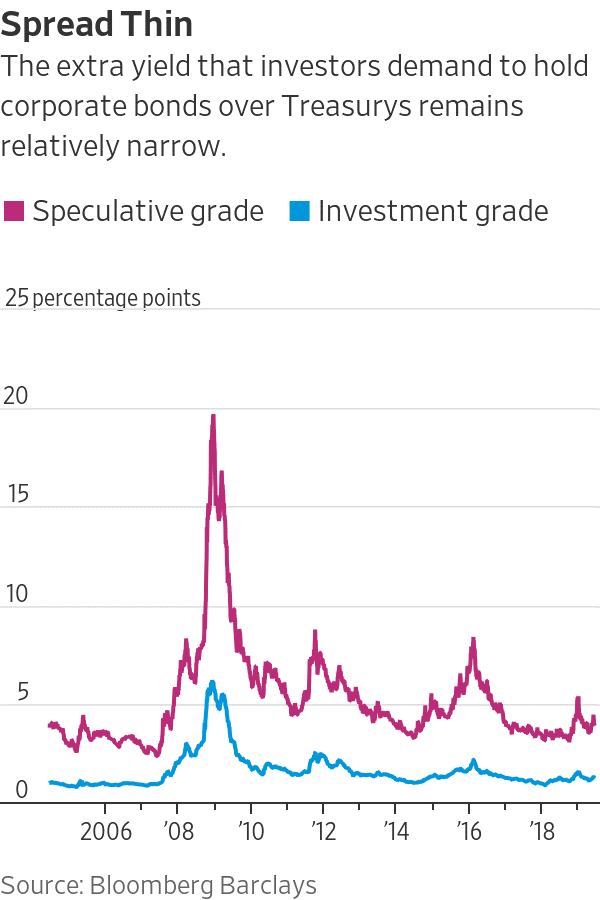

And the market’s reaction to these higher inflation figures? Pretty much the same as the reaction I often get from students during one of my Zoom-based classes (and perhaps even the in-person ones), yawwwwn, if recent yields on ten-year Treasury yields – 1.17% at last glance – and other bonds are any indication. Keep in mind that ten-year Treasury yields were 1.75% at the end of the first quarter. Meanwhile, rates on high yield (read: junk bonds), averaging approximately 3.9% today, have fallen below inflation for the first time.

Plummeting bond yields are as strong as indicator as any that the market seems profoundly

unfazed by recent inflation data.

However, while headline inflation figures may have significant shock value, they become less

concerning when one realizes that more than a third of the inflation figures came from

increases in the prices of used cars. Yes, used cars. So long as Costco continues to charge

only $1.50 for a hot dog and drink, I maintain that inflation is not a longer-term systemic

problem. Rest assured, I will also be watching whether Costco’s hot dogs experience

“shrinkinflation” and will report back as needed.