“If the road is easy, you’re likely going the wrong way.”

–Terry Goodkind

“In a crisis, don’t hide behind anything or anybody. They’re going to find you anyway.”

–Bear Bryant

In recent years, universities across the country have been wrestling with student requests for what are known as “trigger warnings,” explicit alerts that the material they may read, see, or hear as part of a course curriculum might upset them or cause excessive or unwarranted stress. Thus far, after nearly 30 years at UCLA, I have yet to provide any such warnings in my accounting and real estate courses and I do not anticipate doing so in the future. For better or worse, prospective students will just have to prepare themselves in other ways for the discomfort they will inevitably feel when I subject them to discussions about housing policy, a dreaded cold call, and/or a less than fashionable shirt from Jos. A. Bank or Kirkland (as though one exists).

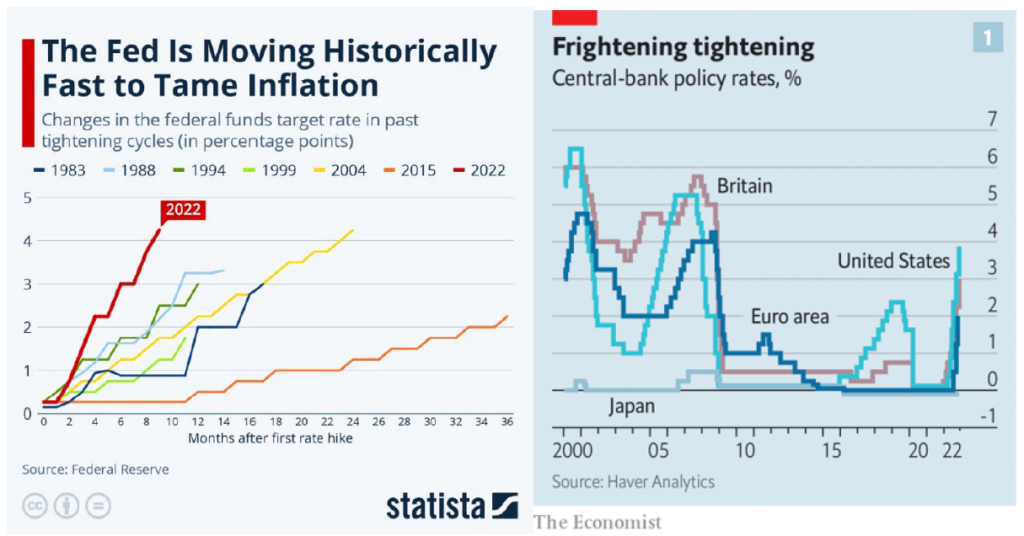

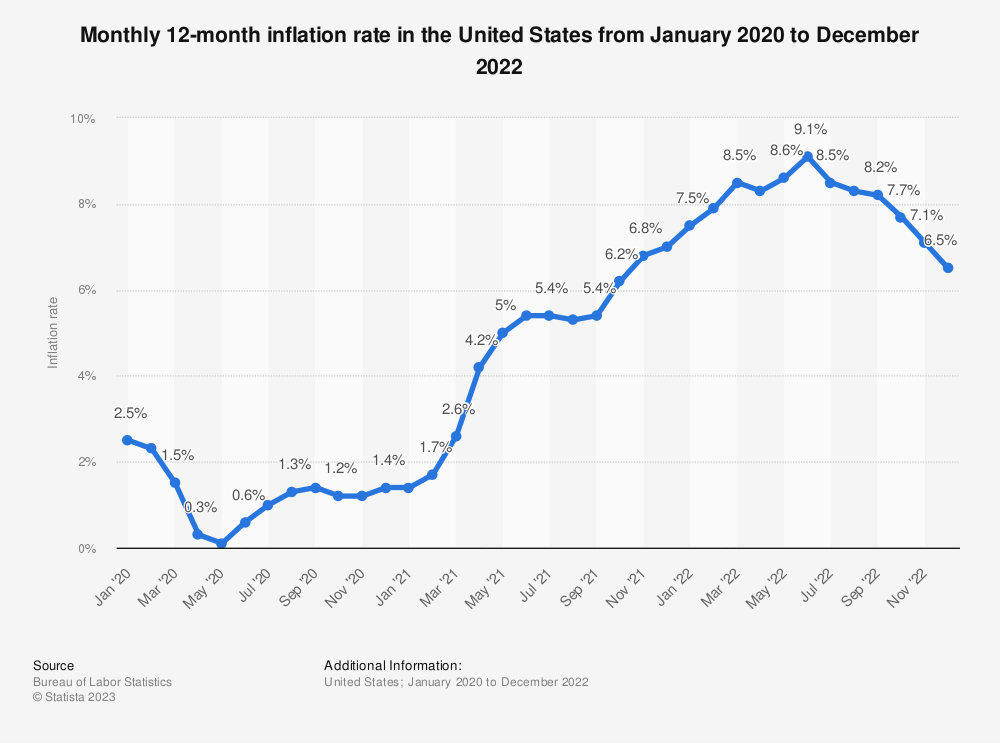

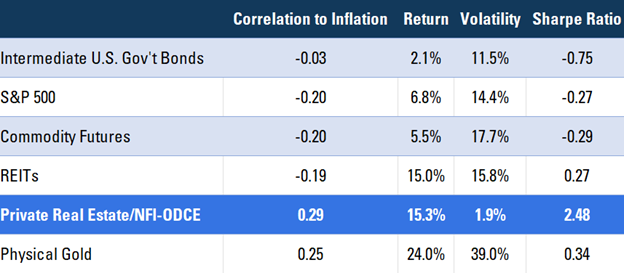

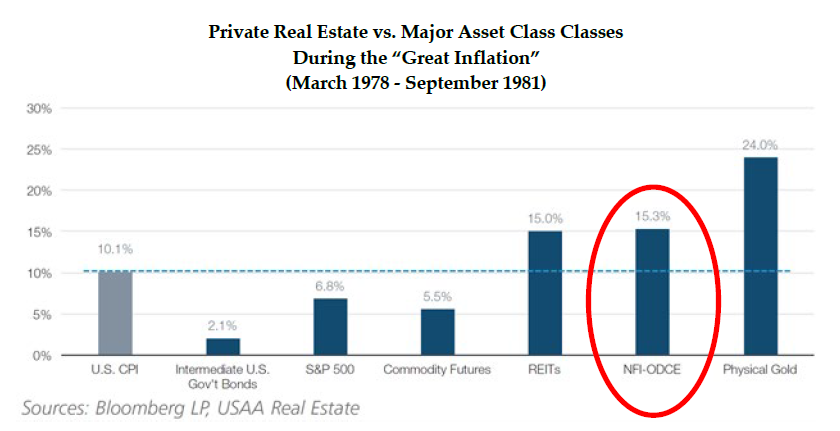

However, as I delve into the second quarter real estate and financial markets and some views about what might lay ahead, please be warned that my opinions, observations, and perspectives may induce nausea, abdominal pain, and/or constipation, essentially the same potential side effects one might experience from taking Ozempic or watching the Mets this season. Here is the upshot. During the first quarter of 2023, longer-term interest rates declined from the end of 2022, providing optimism that the Fed’s unprecedented and aggressive efforts to combat inflation had been successful and that they would return to more accommodative policies in 2024, if not earlier. Such would be beyond welcome to commercial real estate participants.

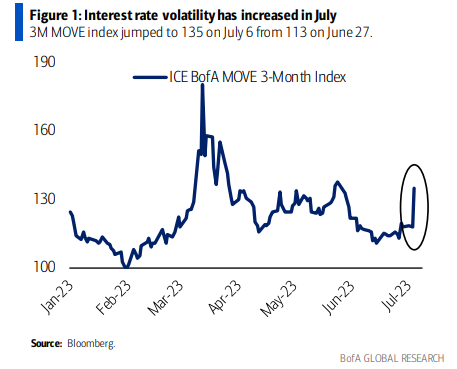

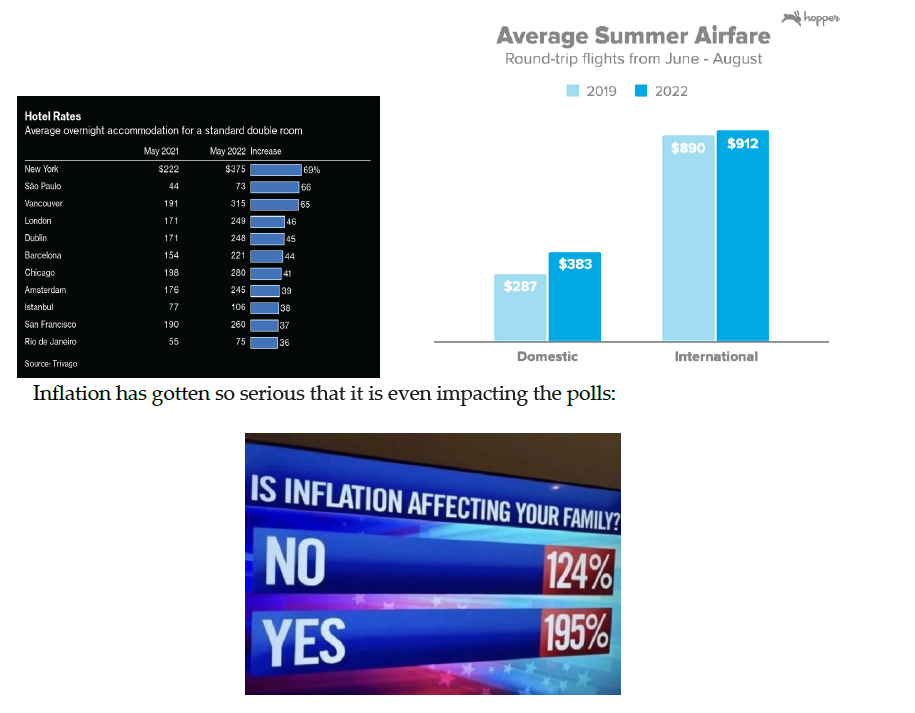

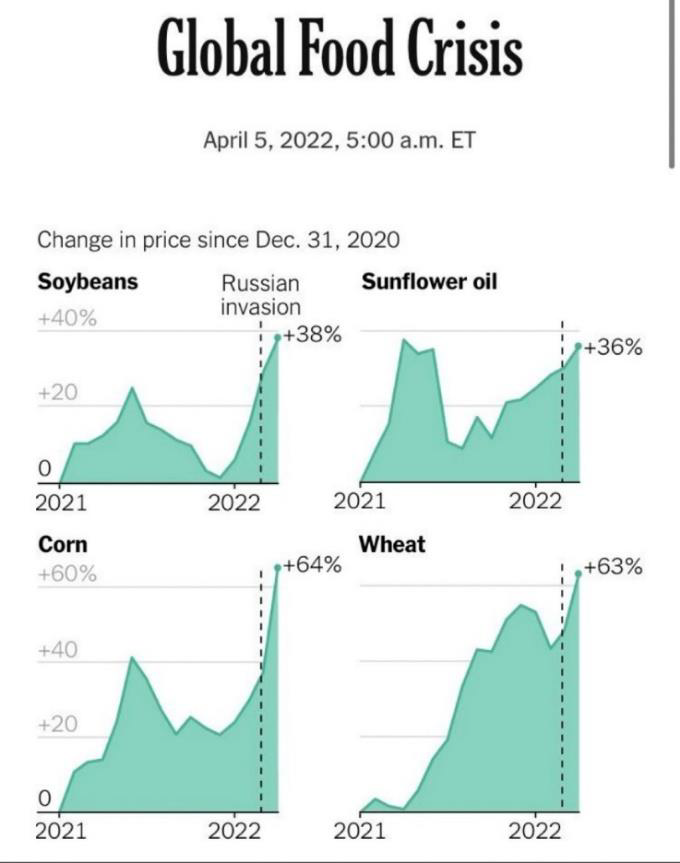

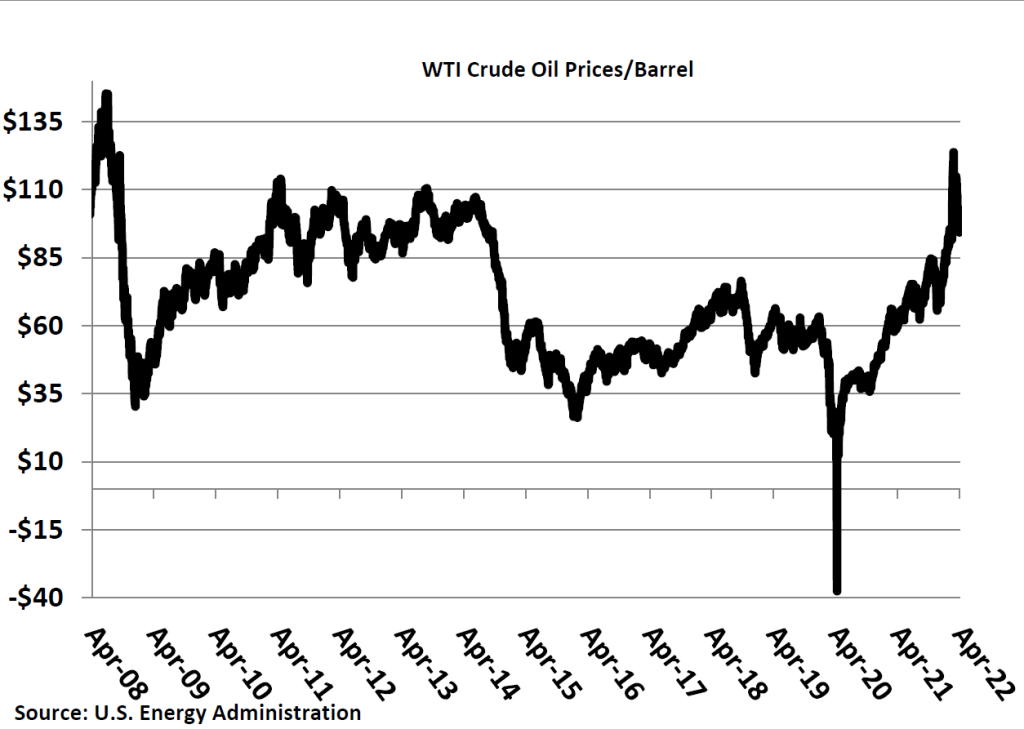

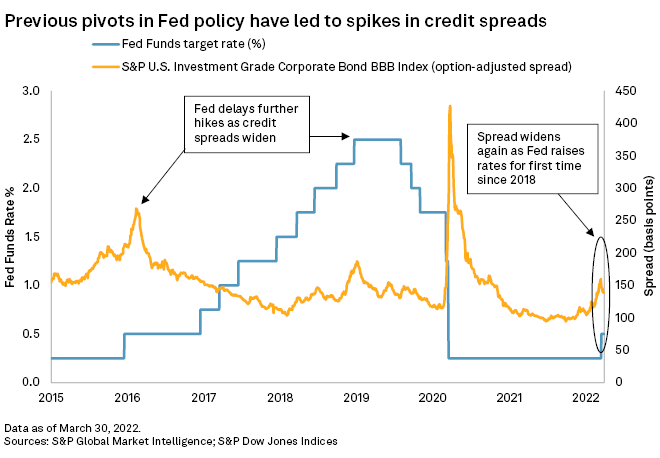

Unfortunately, this optimism was dashed during the second quarter, as inflation – especially the cost of food, housing, energy, and Taylor Swift tickets – remained stubbornly persistent, and interest rates reversed course, which in large part led to the mid-quarter failure of First Republic Bank (May 1st), the second largest in U.S. history ($229 billion in nominal assets) and a growing number of foreclosures, principally in the office market. In turn, the MOVE index, which measures interest rate volatility, has spiked.

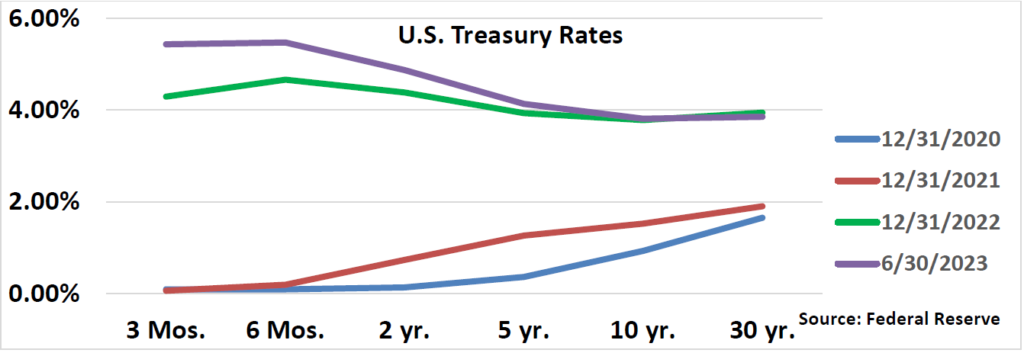

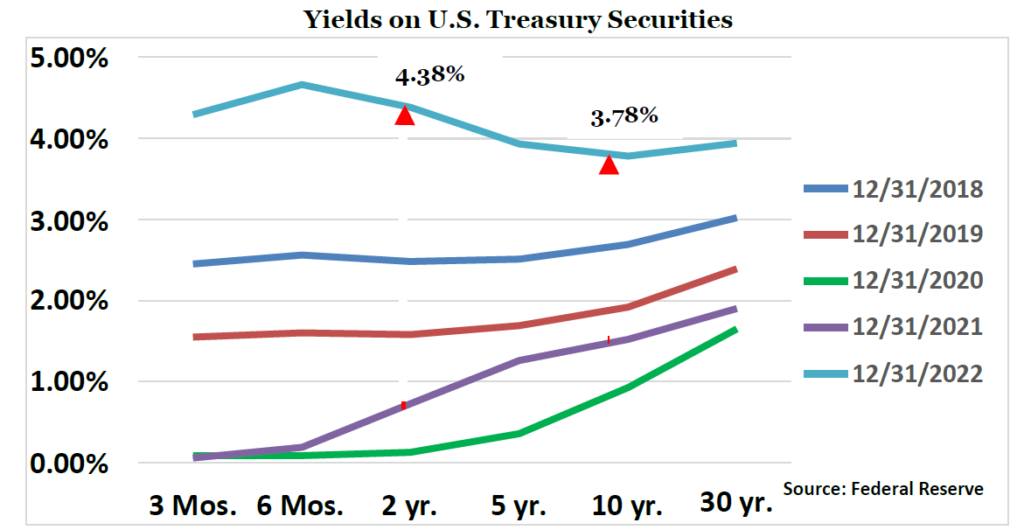

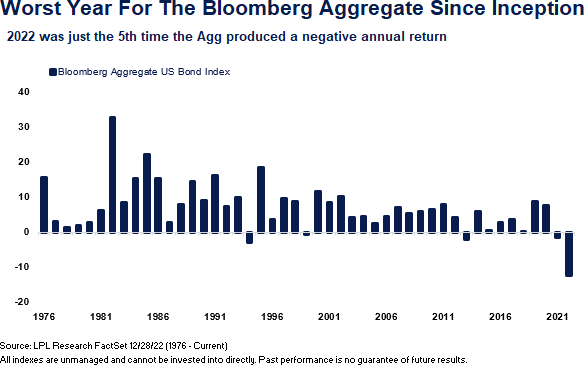

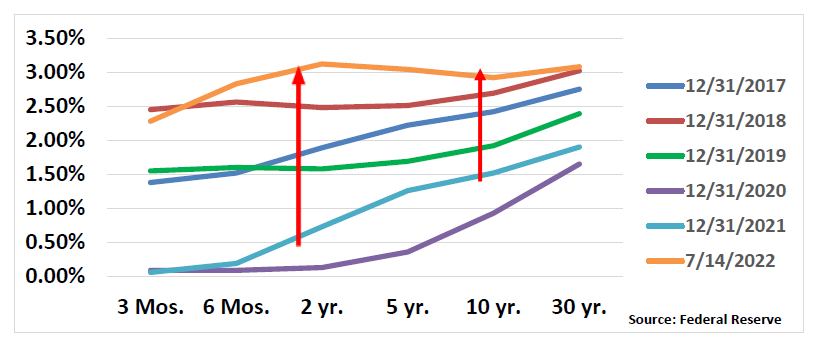

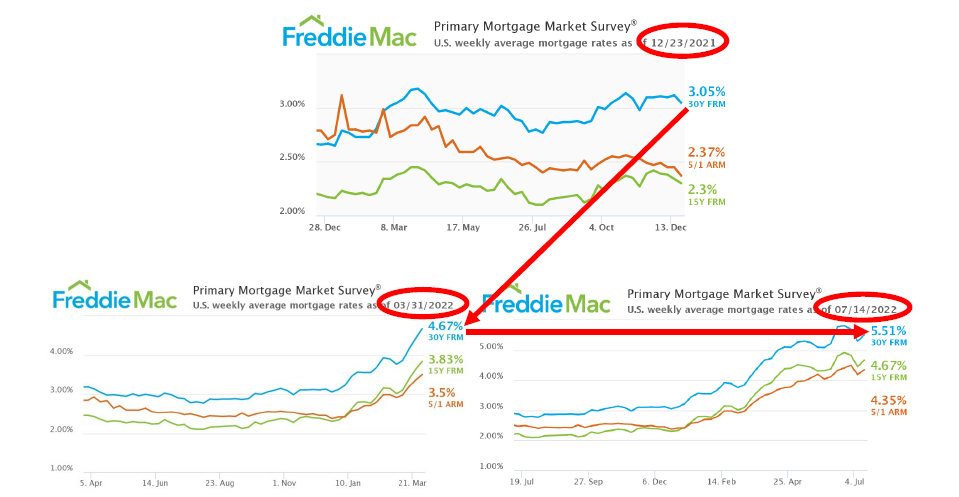

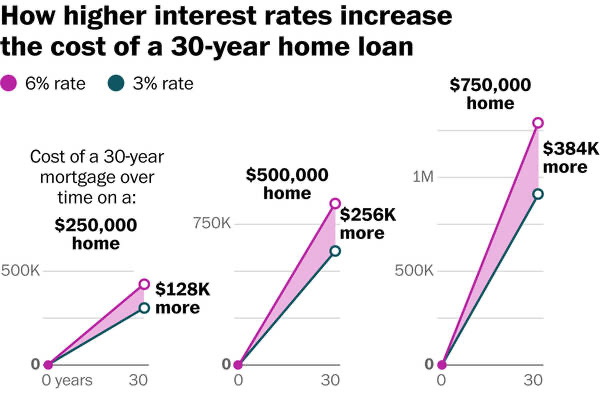

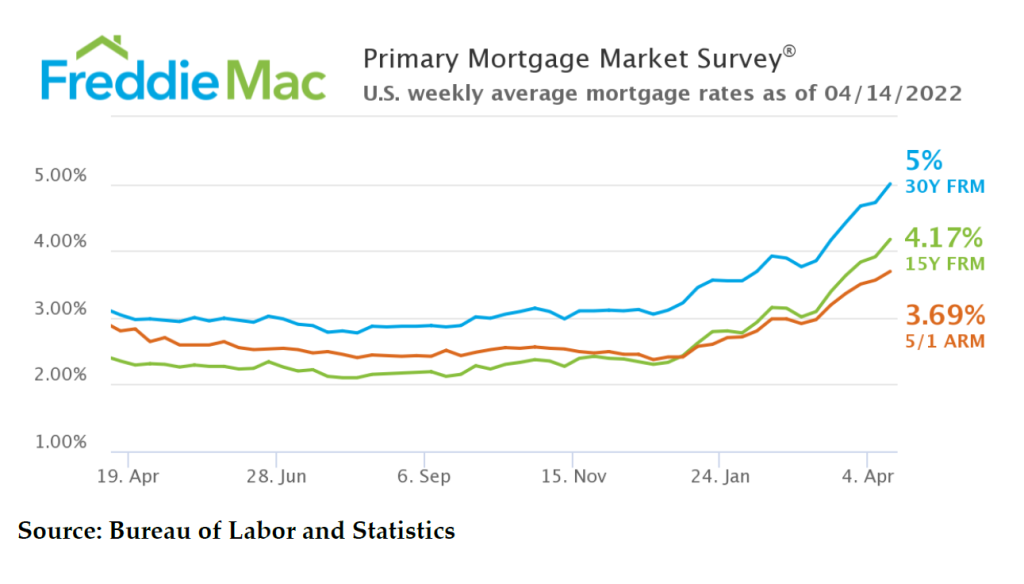

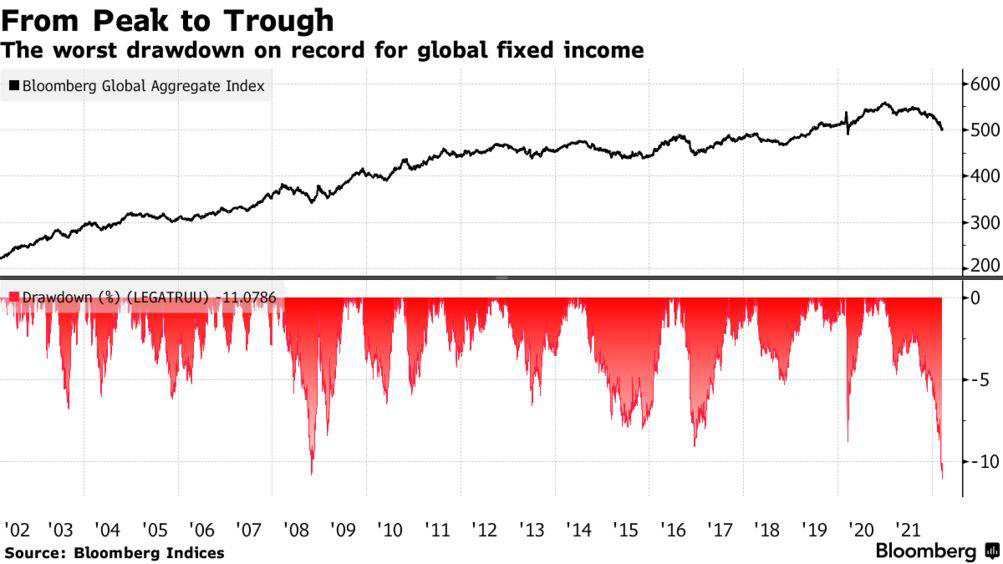

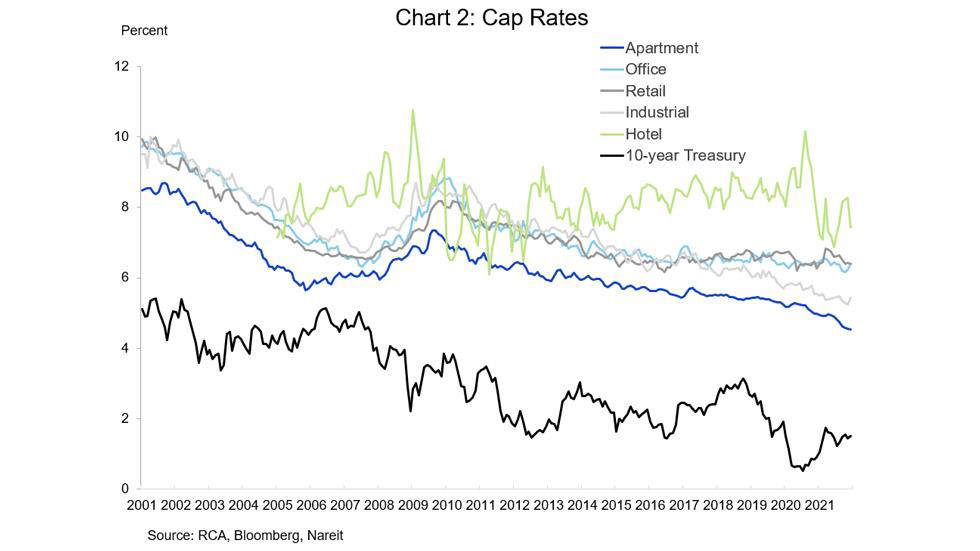

In fact, between June 30th and July 7th, the yield on 10-year U.S. Treasury bonds increased from 3.81% to 4.06%, only to reverse course and decline to 3.83% one week later, on July 14th. Rates on 30-year mortgages increased from 6.32% at the end of the first quarter to 6.81% at the end of the second, and by the end of last week neared 7.0% (6.96%). Two-year Treasury yields ended the second quarter at 4.88%, up from 4.06% at the end of March. And at last glance? 5.04%. Such sharp increases in rates not only reduce the values of bonds and commercial real estate, at least on paper and perhaps temporarily, but add to investor and lender uncertainty.

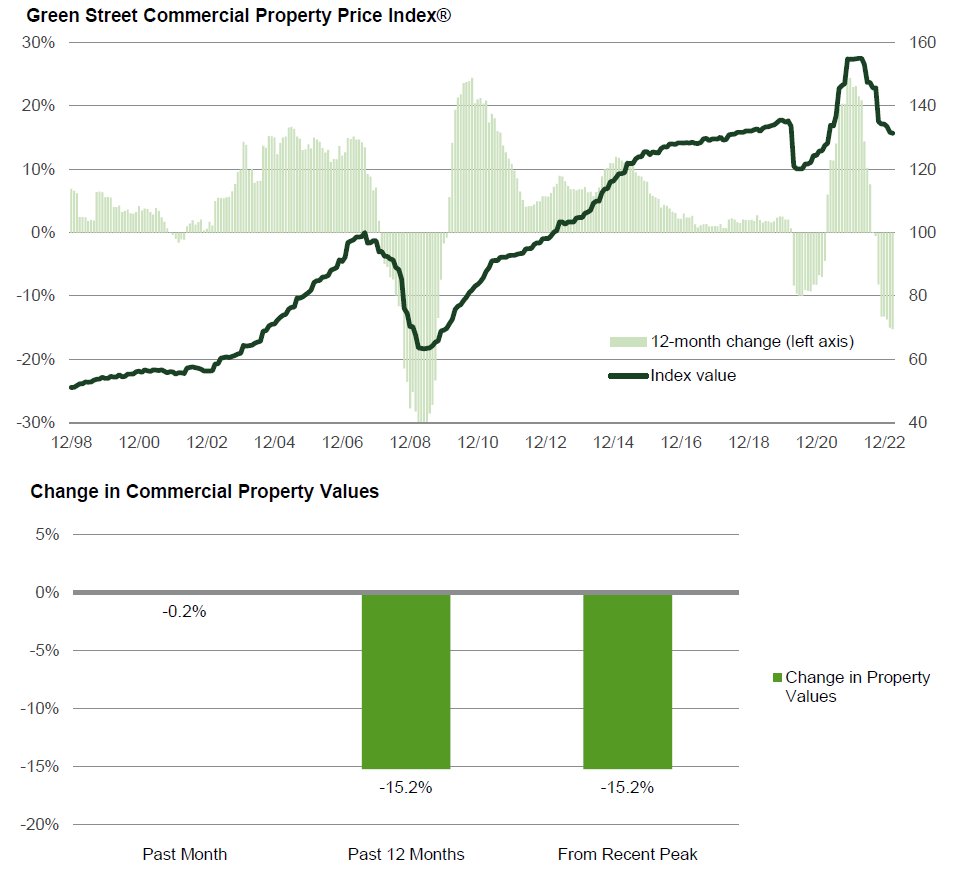

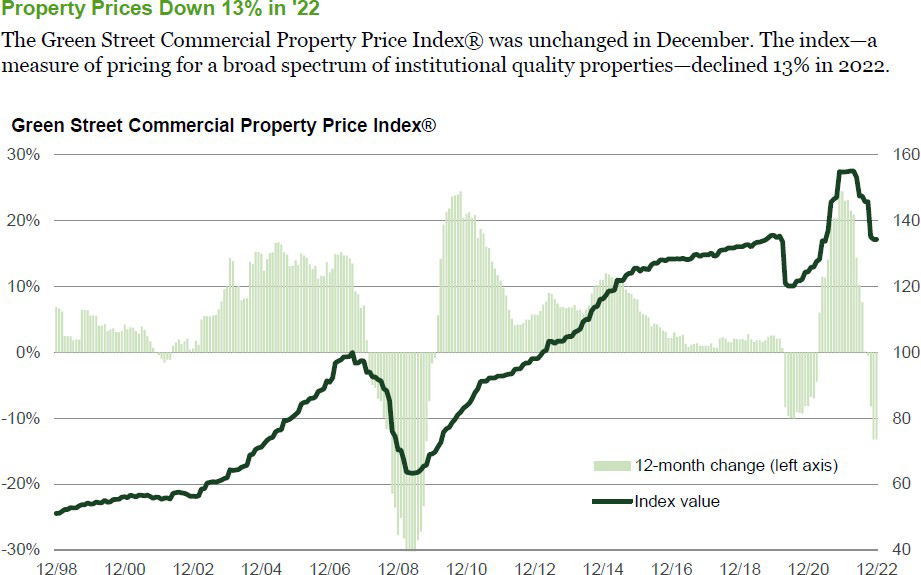

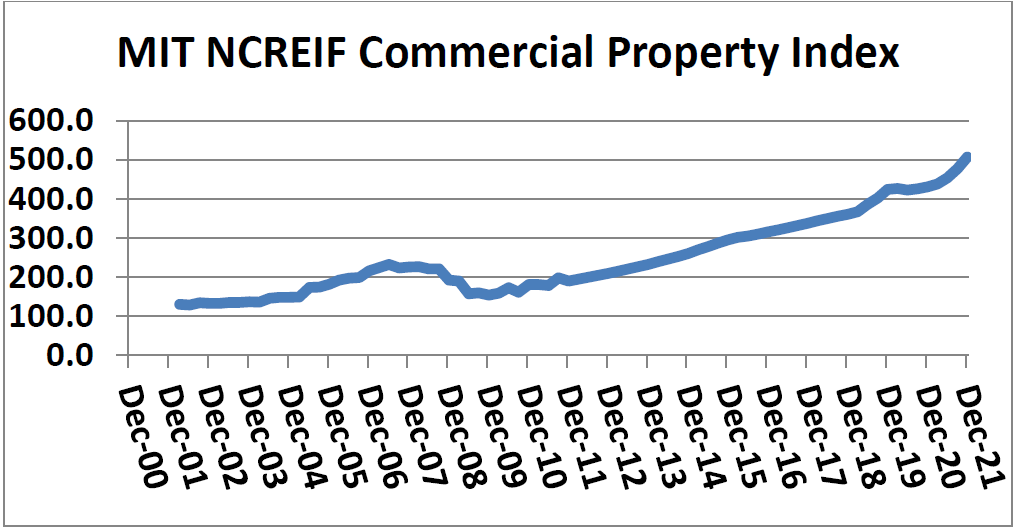

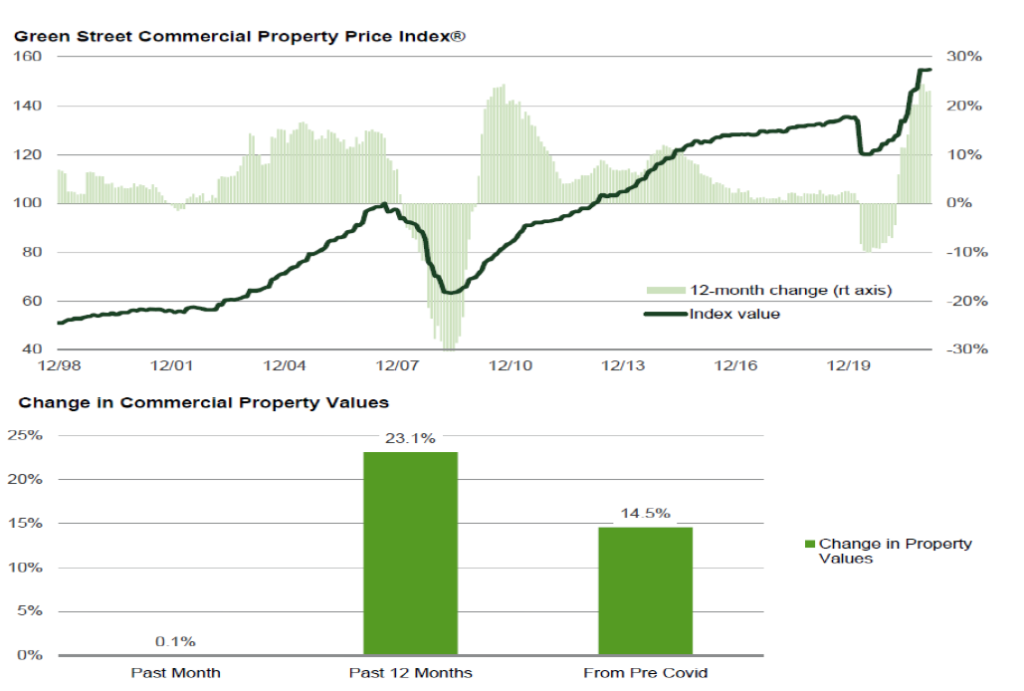

This reversal and increased volatility in interest rates foretell challenges for the commercial real estate industry and its participants, from lenders to principals and sponsors to other service providers (e.g., mortgage bankers/brokers, escrow/title officers, property/asset managers). In short, the next couple of years will likely be a slog, as owners and sponsors work through the stresses caused by higher costs of capital, tightening liquidity, and increased uncertainty. Of course, we have already witnessed significant dislocation in the office and retail sectors, with a large number of foreclosures and failures experienced from coast to coast…and sometimes in-between. According to a new report from MCSI Real Assets, some $64 billion of commercial real estate is now distressed, while more than $150 billion is “potentially troubled.”

Moreover, previously “hot” segments of the commercial real estate space – multifamily (including student and senior housing), industrial, and data centers – while having far better underlying fundamentals, are not immune and increased delinquencies, notices of default, and foreclosures in these sectors are inevitable. In many cases, the problem is not and will not be the real estate itself – rents, occupancy rates, and/or pre-debt cash flow – but merely untenable capital structures and excessive leverage in a higher rate environment. In fact, while the Clear Capital portfolio continues to mostly track forecasts and operating cash flow projections, it is the debt, especially that which is floating rate (even hedged), which is proving challenging, especially for legacy assets. On paper, nearly all commercial real estate values are probably down anywhere from 15 to 30%, merely from increases in interest rates. While perhaps temporary, these unrealized losses are not without consequence.

In fact, earlier this year, Veritas, San Francisco’s largest landlord, defaulted on a huge loan (at least $448 million) encumbering nearly 2,500 apartment units in ninety-five different buildings throughout the city. The largest mortgage loan (non-performing) being shopped secures a 75-building portfolio consisting of 2,149 rent-controlled units and forty-five commercial spaces, mostly ground-floor retail. The locations are generally good, and we are talking about San Francisco, though the city has been plagued by homelessness, a softening technology market, and a flight of retail and white-collar office workers, as has been widely publicized.

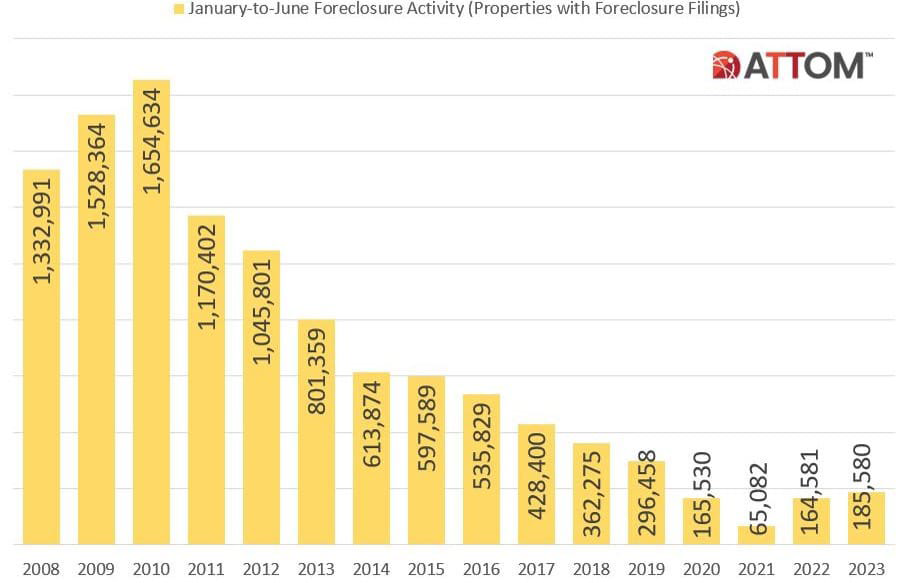

While foreclosure activity during the first half of 2023 pales in comparison to that experienced in the Great Financial Crisis, foreclosure activity has picked up in recent months and I sense we are still in the early stages of this cycle, which will likely have a long(er) trough. These realities should present potentially attractive investment opportunities and we are excited about our recent acquisition of the “IE3,” a portfolio of three assets in the Inland Empire. However, with less liquidity, higher cost of capital, and more conservative underwriting, closing on even appealing opportunities won’t be a slam dunk. Fear and uncertainty are unwelcome bedfellows to acquisition endeavors.

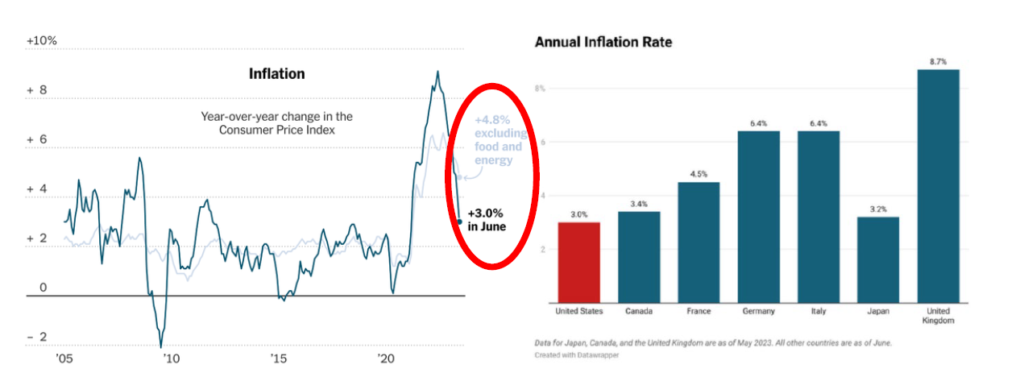

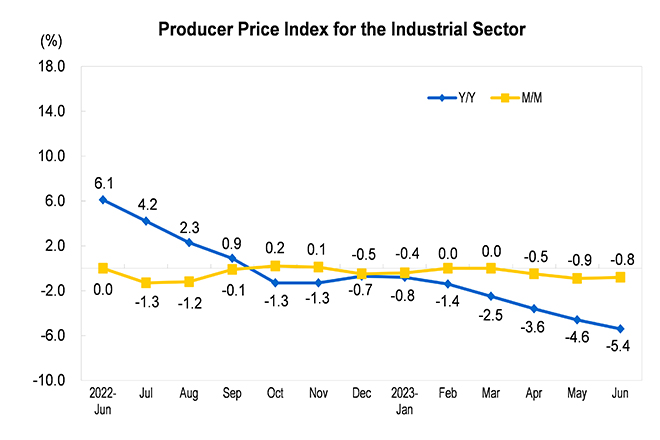

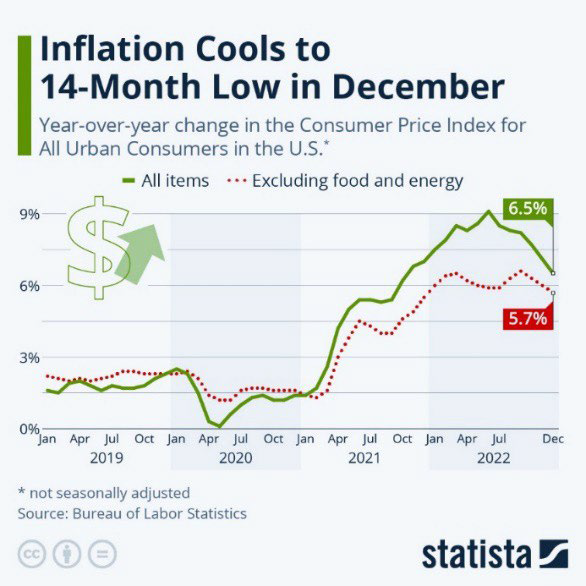

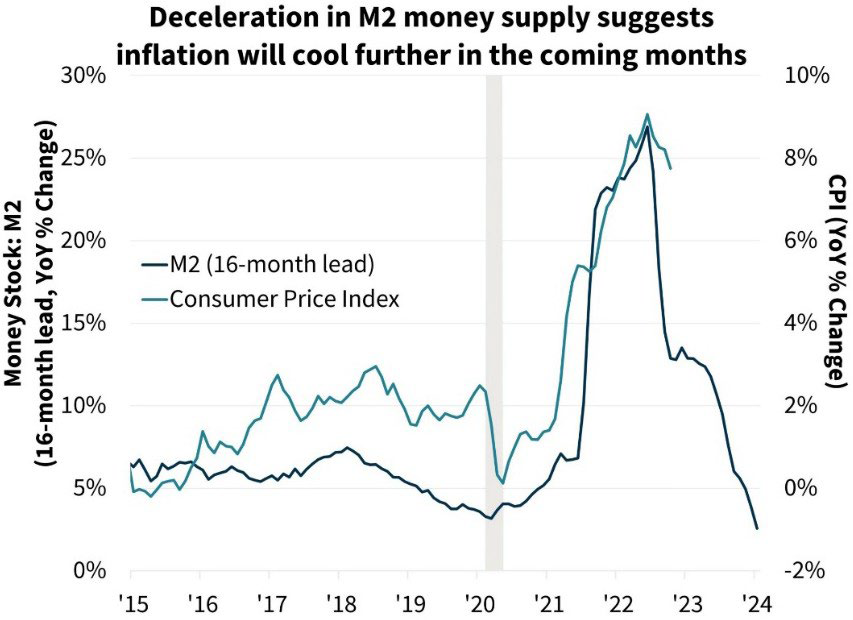

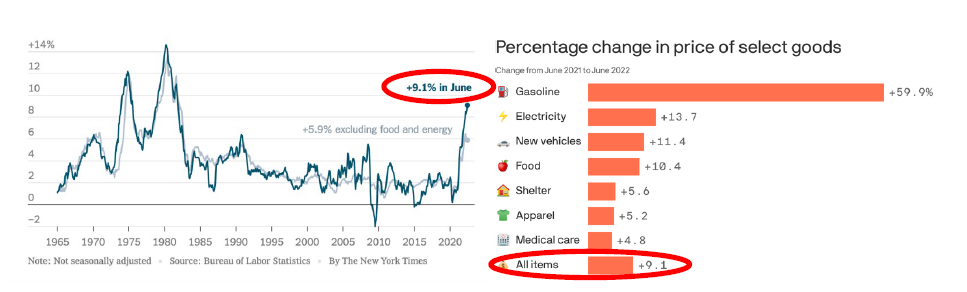

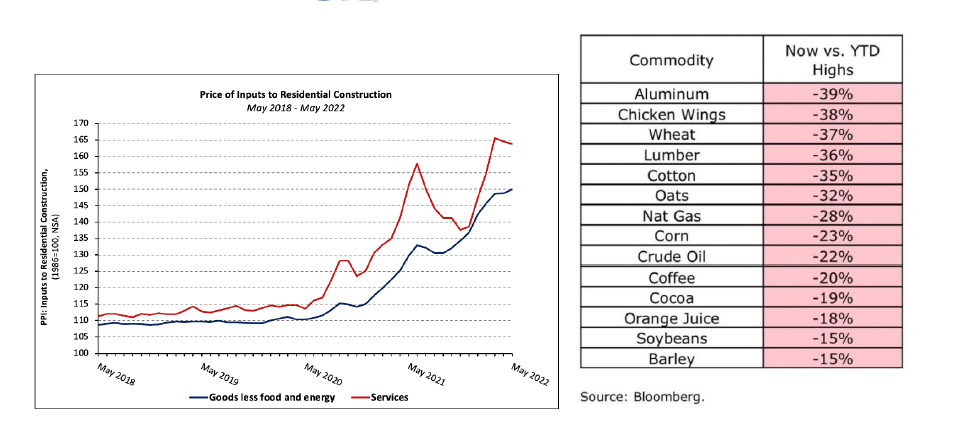

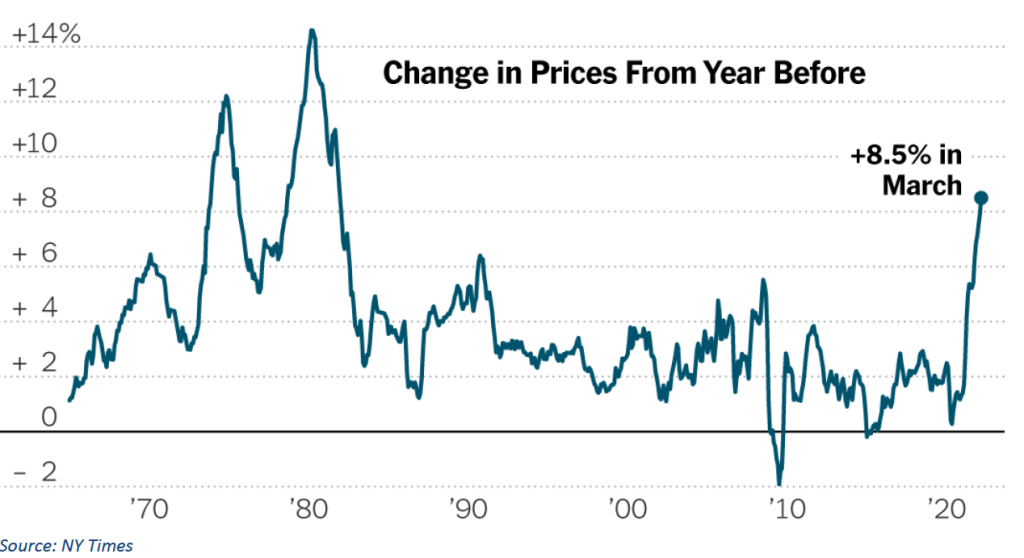

And inflation data itself? Both consumer and producer prices have moderated, with inflation declining for eleven straight months. The Consumer Price Index was up 3.0% in June (4.8%, excluding food and energy costs), year-over-year, versus a whopping 9.1% a year ago. The U.S. now has the lowest inflation rate among developed nations, despite the political rhetoric.

And producer prices? The June Producer Price Index was down 0.8% between May and June, and 5.4% from June 2022 to June 2023. Producer prices have declined even faster than consumer inflation, so inflationary pressures are definitely easing. However, the Fed’s two percent inflation target still seems aways away.

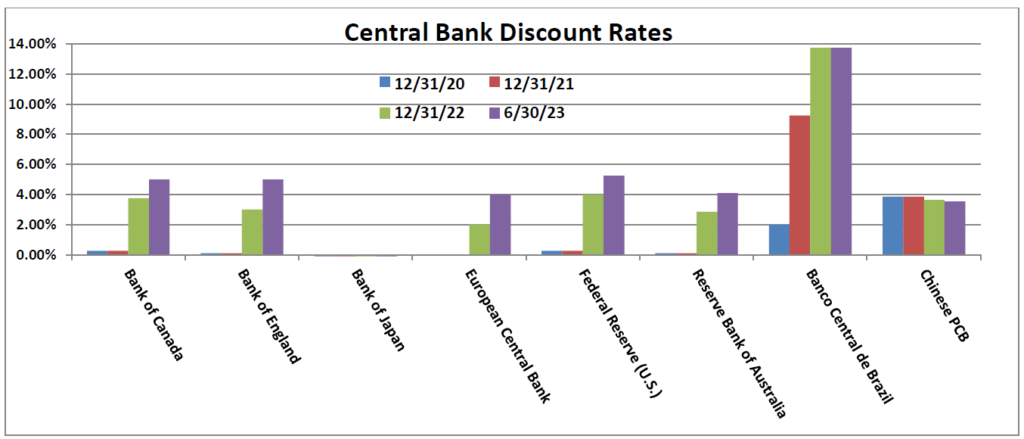

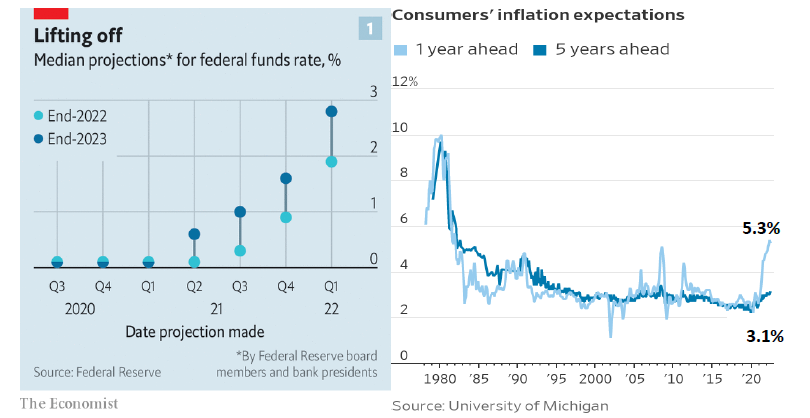

Regardless of moderating inflation, June witnessed the world’s major central banks delivering the largest number of monthly interest rate hikes year-to-date, surprising investors and signaling the possibility (if not probability) of more tightening ahead as policy makers grapple with inflationary pressures. Seven of the nine largest central banks hiked rates last month, while two opted for no change (including the U.S.). Both Norway and the Bank of England increased rates by a larger-than-expected fifty basis points, while Canada and Australia also resumed their rate hiking ways. Sweden, Switzerland, and the European Central Bank also tightened, taking the collective tally of rate hikes to 225 basis points last month. May witnessed six rate hikes. Across the entire G10 (group of eleven industrialized nations), there have been twenty-eight rate hikes this year, totaling 950 basis points, and since Norway started raising rates in September of 2021, major central banks have increased rates by a combined…3,765 basis points. Yowza.

The increase in rates and the specter of persistently higher inflation are probably the biggest news stories of the quarter, narrowly beating out the discovery of a small bag of cocaine in the White House (wasn’t mine, I swear), the departure of Pat Sajak as host of Wheel of Fortune, the tragic Titanic submarine implosion, a failed coup (or whatever the heck that was) in Russia, and the predictable (if not unnecessarily politicized) conclusion of debt ceiling negotiations closer to home.

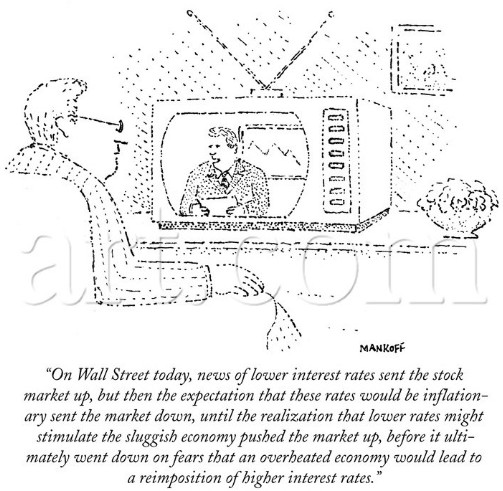

Regardless, conflicting data appears around every corner, making economic, financial, and market predictions about as difficult as interpreting Mona Lisa’s beguiling smile or anticipating the winner of an Elon Musk-Mark Zuckerberg cage match. Analyst estimates of global GDP are wide, twice the range of predictions made in previous years, and the word “uncertainty” appears more than sixty times in the most recent International Monetary Fund’s Global Economic Outlook. One day the Dallas Fed Chief, Lorie Logan, says that interest rates should rise further, and then, on the very next day, Fed Chief Jerome Powell says something far less hawkish. These conflicting narratives remind me of that memorable scene from 1982’s Fast Times at Ridgemont High, when Sean Penn (or rather, his character, Jeff Spicoli) responds to a friend after totaling this friend’s brother’s new Camaro and the friend’s subsequent admonition…’My brother is going to _hit! He’s going to kill us!’ to which Spicoli replies, ‘Make up your mind, dude! Is he going to _hit or is he going to kill us?’

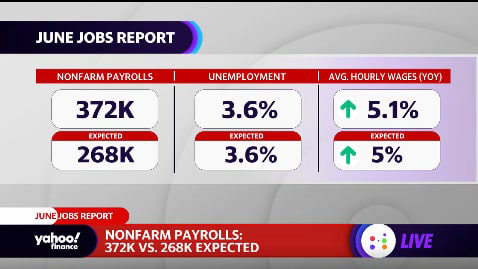

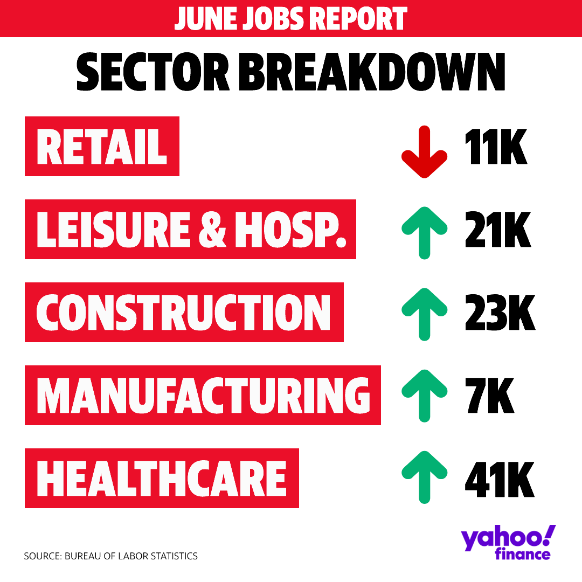

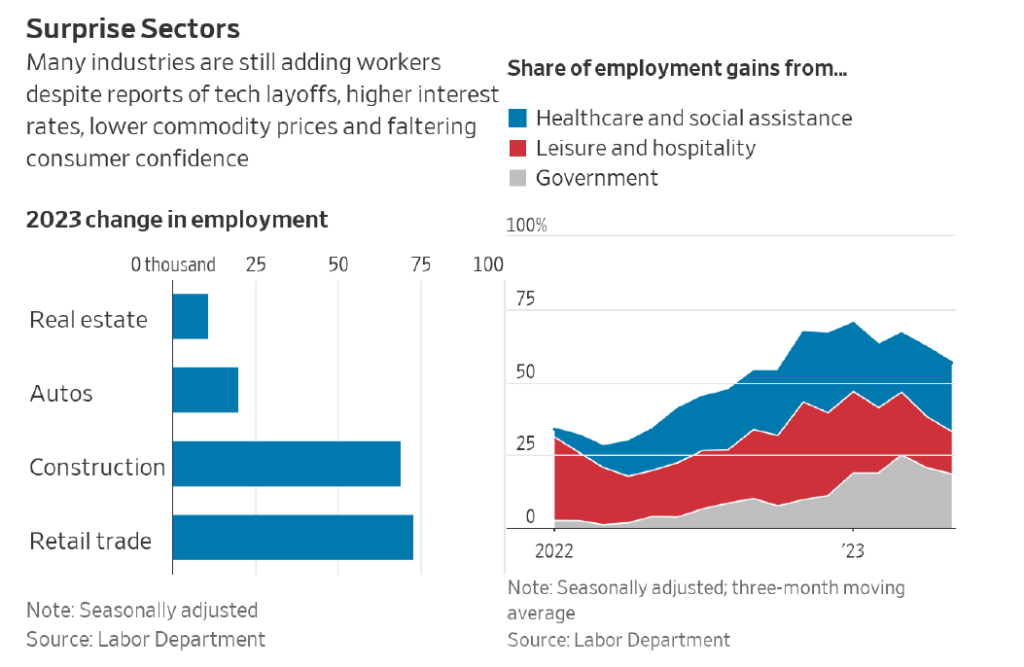

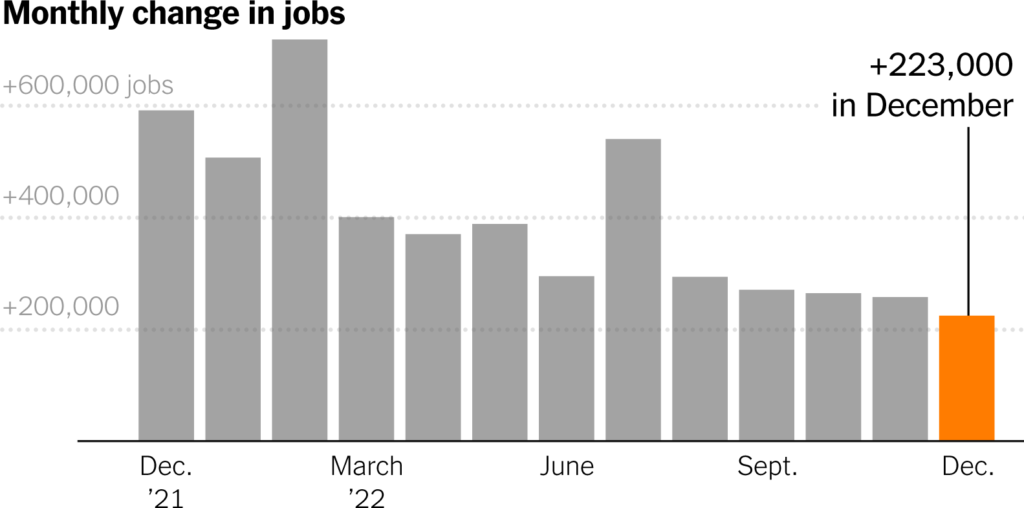

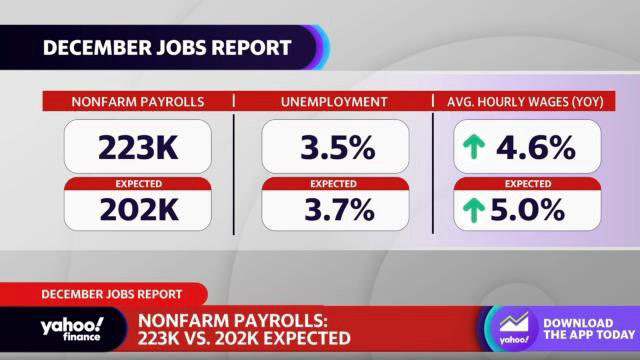

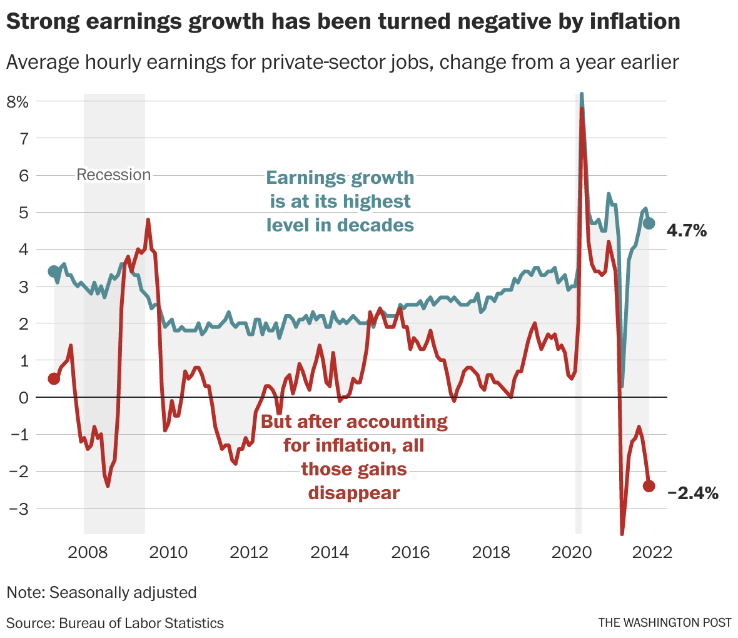

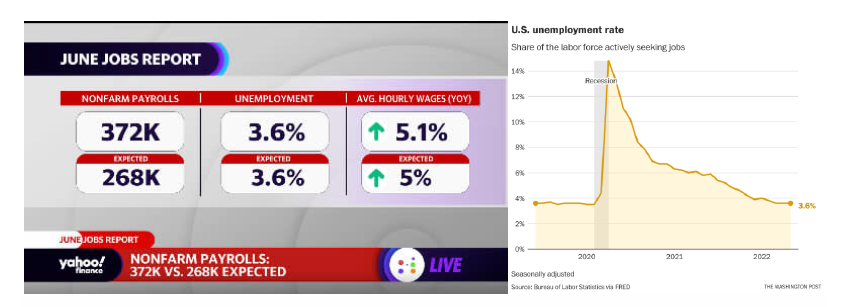

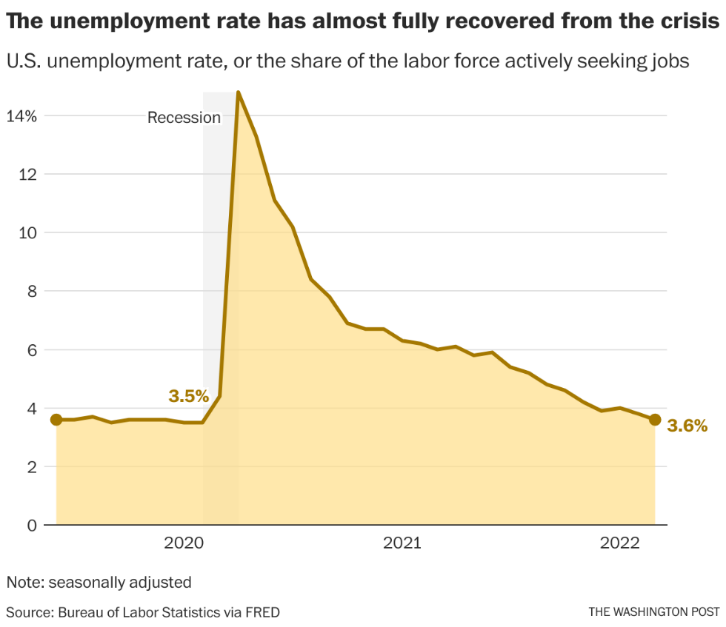

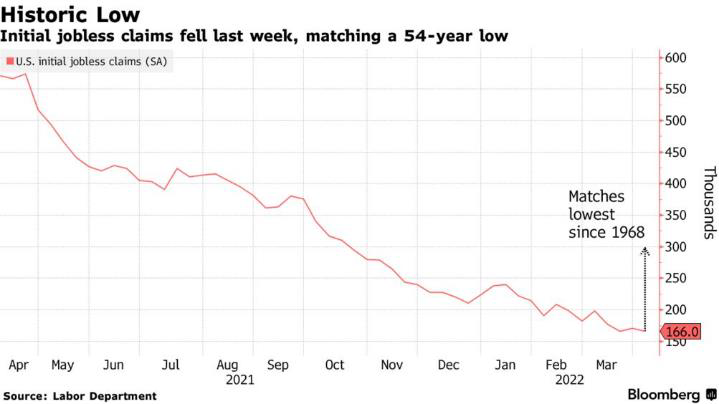

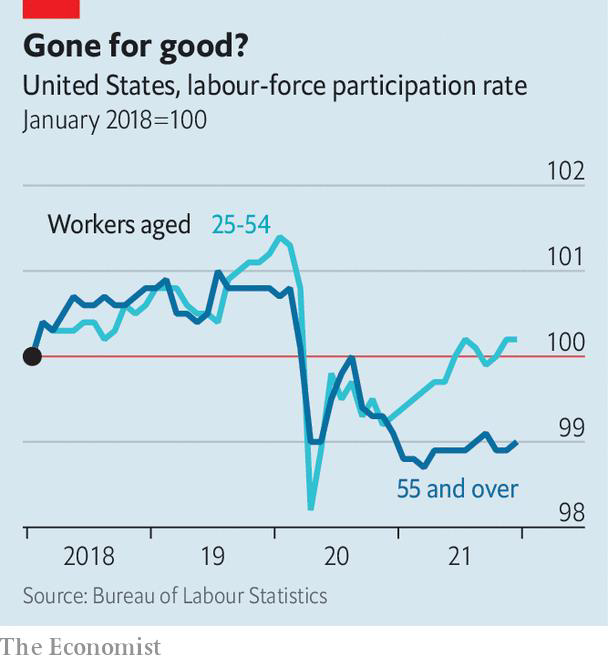

Let’s start with the job market, since the Fed is tracking this data closely in setting interest rate policy. In short, it remains surprisingly robust, rekindling fears of persistent inflation and higher interest rates. In June 372,000 new jobs (non-farm) were added versus the 268,000 expected. Wages increased 5.1%, year-over-year. Despite the odds, the U.S. labor market continues to add jobs and even companies in the crosshairs of rising interest rates are holding onto or adding workers. Builders, architects and engineers, real-estate agents, vehicle manufacturers and other businesses typically sensitive to higher borrowing costs have actually increased employment levels this year, though I sense this may reverse in the coming months.

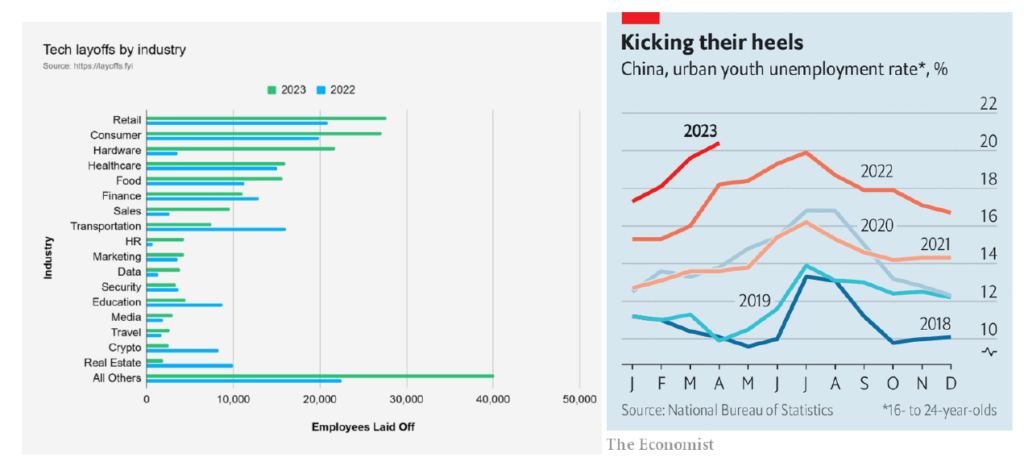

These job gains, along with much larger increases in industries still trying to claw back workers lost during the pandemic, have added up to almost 1.6 million new jobs in the first five months of 2023, outpacing forecasts. Meanwhile, other firms continue to reduce headcounts. Although merely an anecdotal (and unsubstantiated) data point, I heard a rumor that a surprisingly large number of MBAs from UCLA Anderson did not have job offers at graduation time last month as traditional recruiters in tech (largest hirers in recent years), finance, consulting, and real estate have pared back hiring needs. Other firms have pushed back start dates. On a somewhat related note, I recently read that the jobless rate among Chinese 16- to 24-year-olds rose to a whopping 21.3%, compared to 7.5% here in the U.S. Yowza, again.

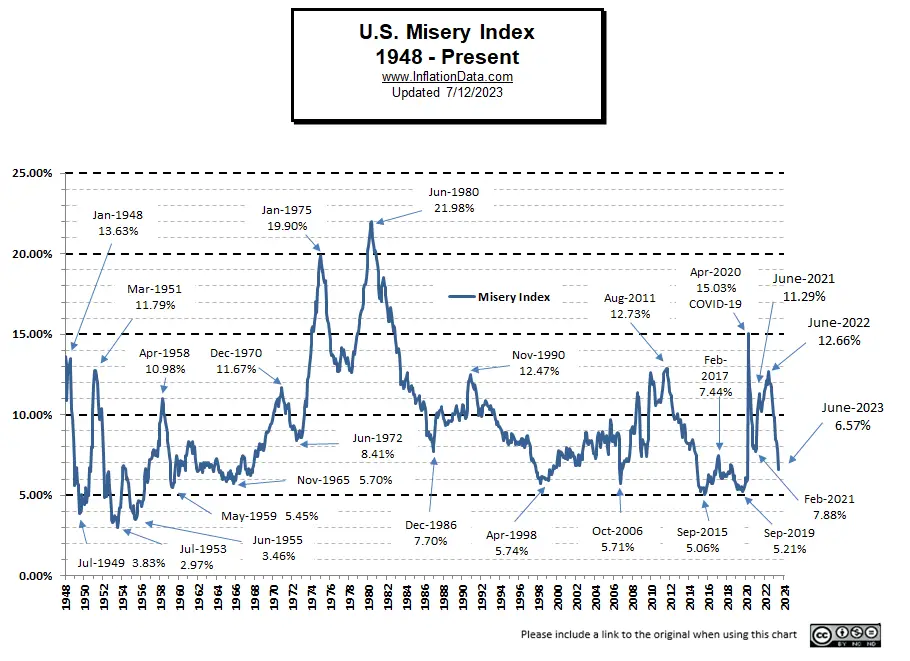

Meantime, the so-called, but appropriately monikered “Misery Index,” computed by adding the previous 12-month change in the Consumer Price Index percent change and the unemployment rate, has been trending downward, to a recent 6.57% in June. The last time the Misery Index was this low was before Covid, in September 2019. So, would someone please tell me why I don’t feel better…or at least less miserable?

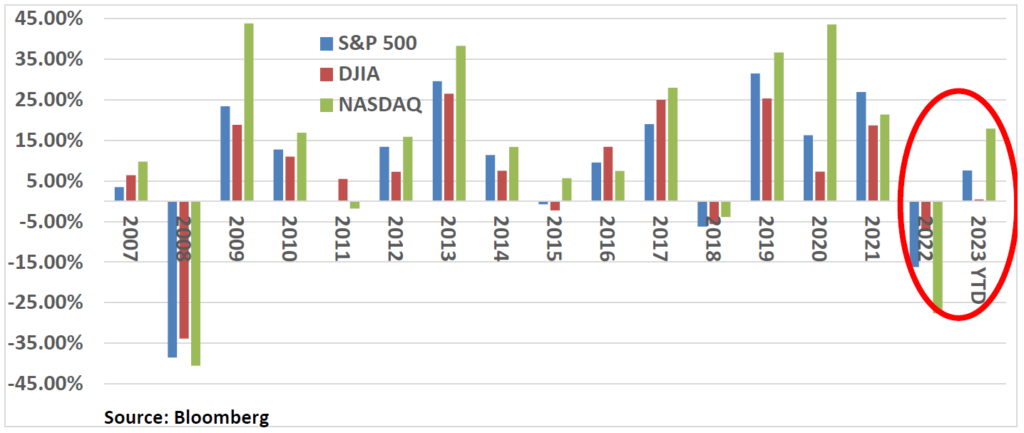

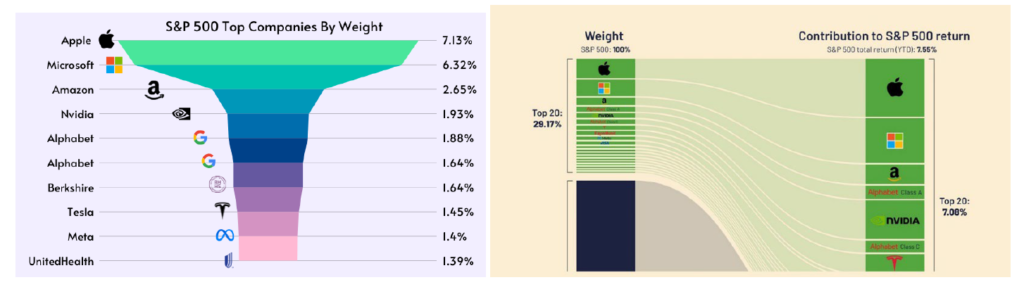

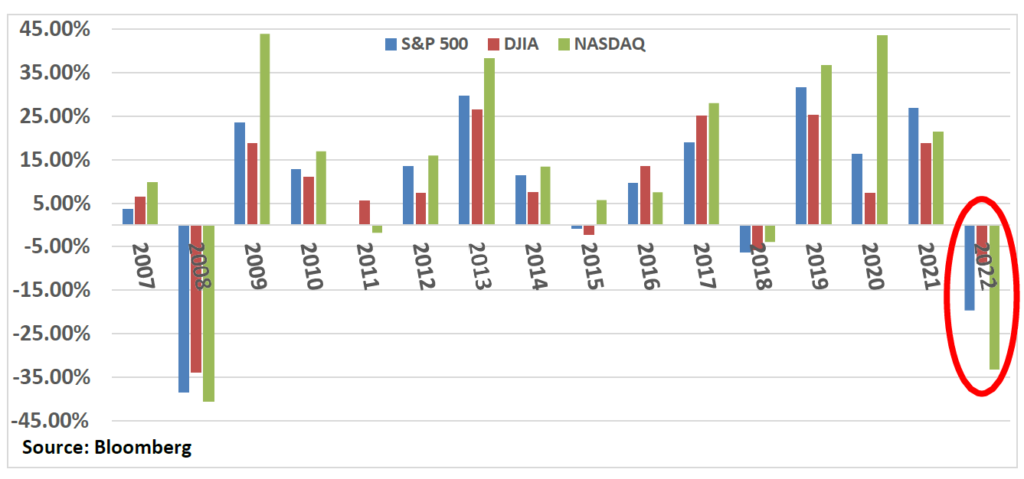

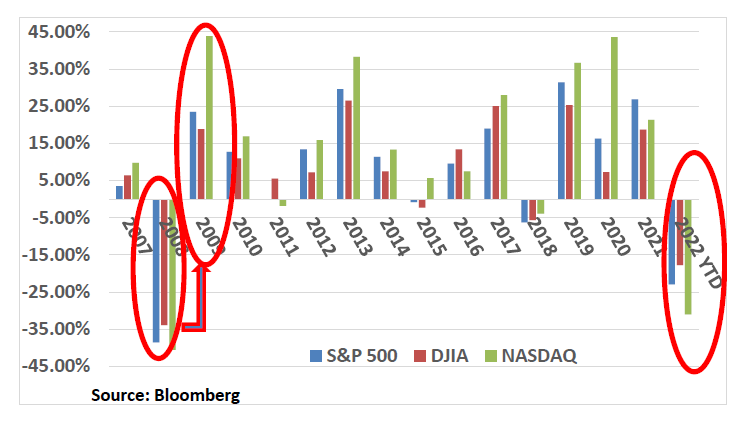

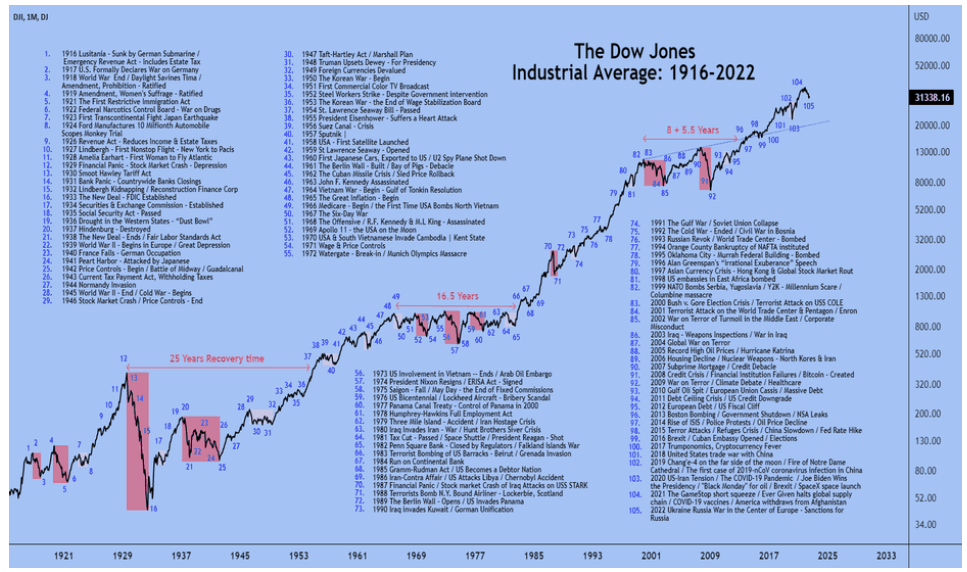

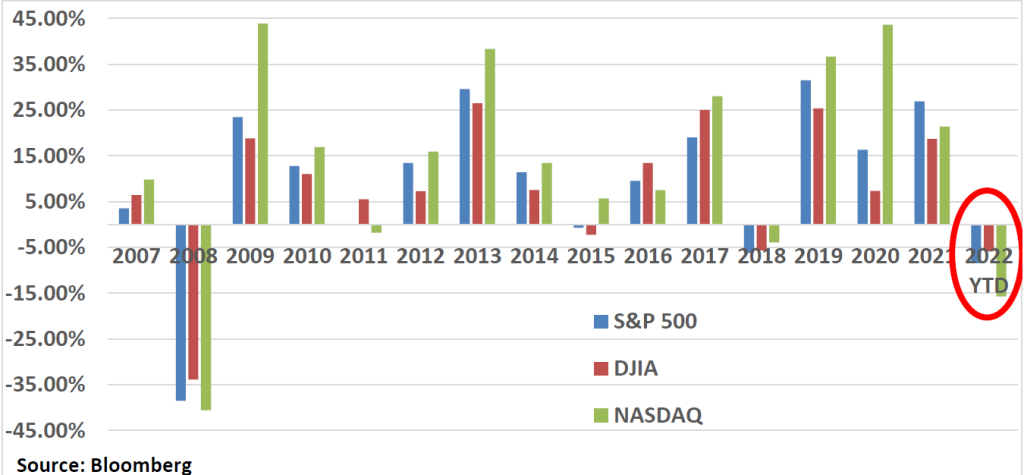

How about the equity markets? Well, the S&P 500 is up 17.4% this year, with the tech-heavy NASDAQ gaining a whopping 34.9% thus far, its best first half in 40 years. If you compare the equity markets between 2009-2010 and 2022-2023, they look eerily similar, with a significant downturn followed by a reversal the following year.

However, when we peek under the equity market hood, there is more (or less) than meets the eye. In fact, when I recently read a headline that the S&P 500 and NASDAQ had reached their highest levels since last August and that the price rise was almost enough to represent a “bull market” (generally defined as a 20% rise in the S&P 500), I did a double take. Bull market? Really? This has to be the least fun and exciting bull market I have ever experienced.

And no wonder. This “bull market” has really been powered by a small number of mega-cap tech stocks: Apple, up 38% this year. Nvidia, up 165%. Tesla, 128.5%. Meta (Facebook), 151.5%. In fact, just twenty stocks, including the likes of Apple, Microsoft, Amazon, Nvidia, Alphabet (Google), Meta, Berkshire Hathaway, Tesla, and United Health, represent over 90% of S&P 500 returns through May, despite comprising less than 30% of the Index. In fact, on Friday of last week, Nvidia’s stock price moved up and down so substantially in a single day that the implied value of the intraday swing (change in market value) was larger than the market capitalization of four hundred other companies in the S&P 500. That’s just nuts. Another “yowza” seems warranted.

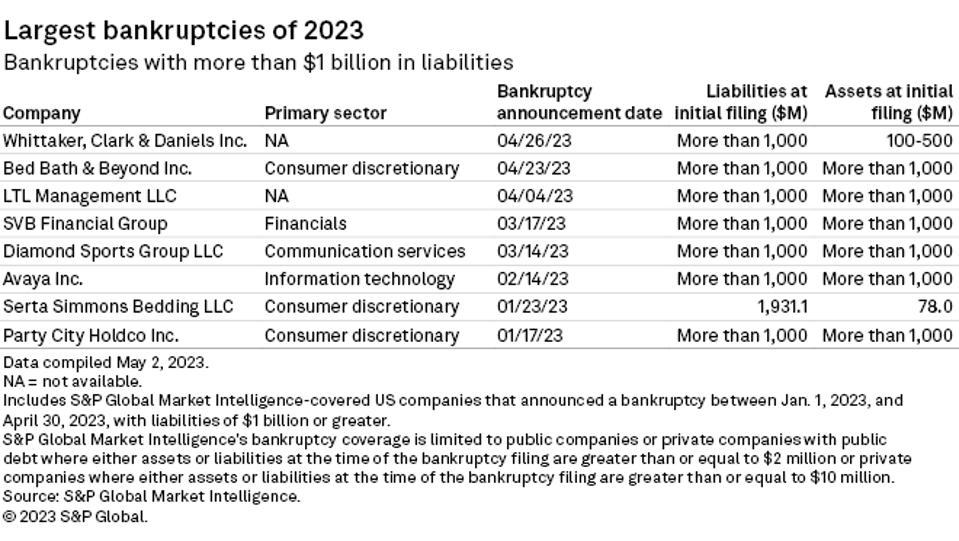

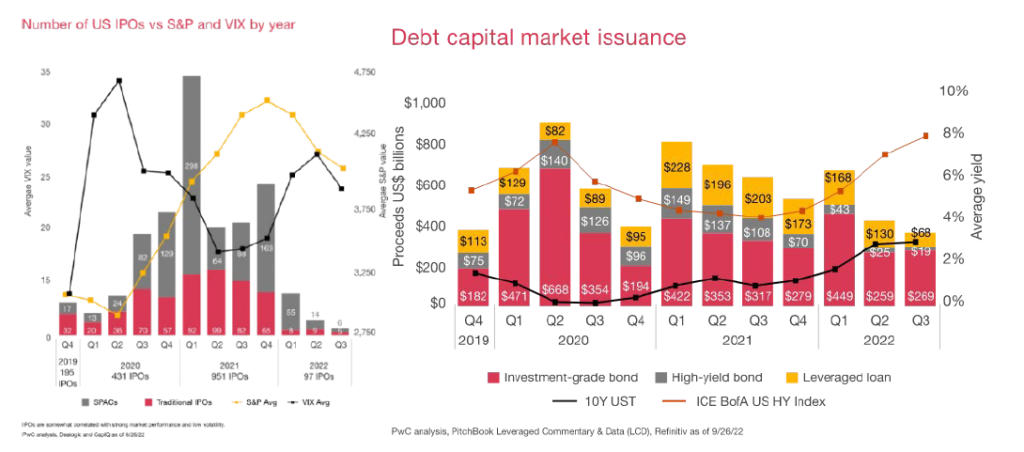

Meantime, corporate defaults rose last month, with forty-one in the U.S. so far this year, more than double the same period last year, according to Moody’s. Heavy debt loads, high interest rates, and uncertain economic conditions are beginning to take their toll. The number of bankruptcy filings in the U.S. this year has also sharply risen to levels not seen since 2010. Through June, there were 324 bankruptcy filings, not far behind 2022’s total of 374, according to S&P. The list of failures includes Silicon Valley Bank and Bed Bath & Beyond, of course, but others like regional sports network owner, Diamond Sports, and the information technology firm, Avaya.

And how about the residential real estate markets, both single- and multifamily? How are they holding up in these challenging markets?

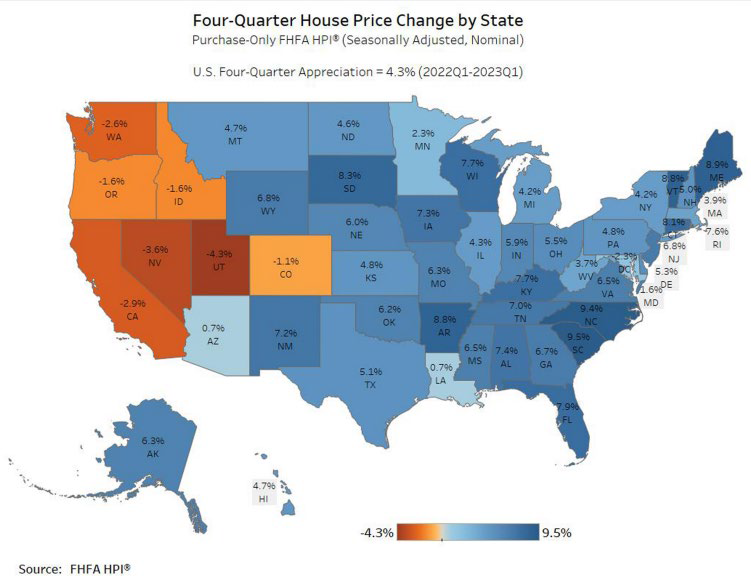

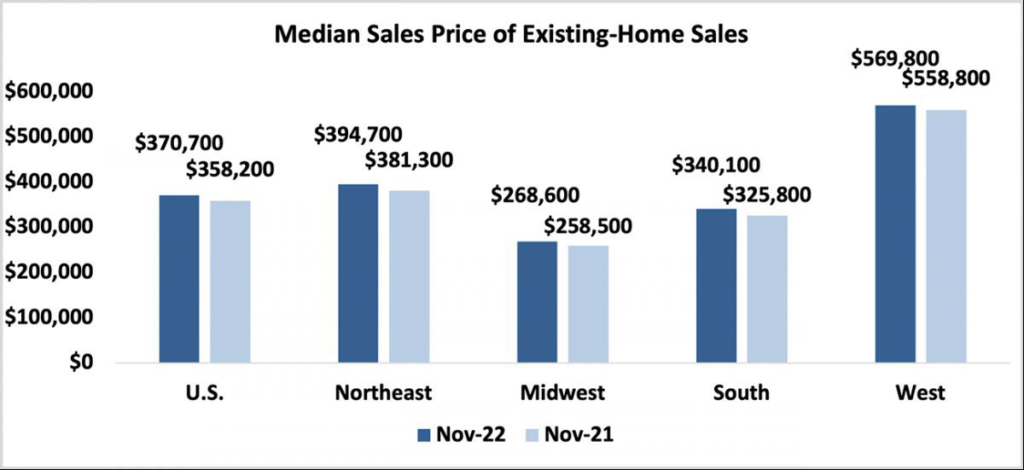

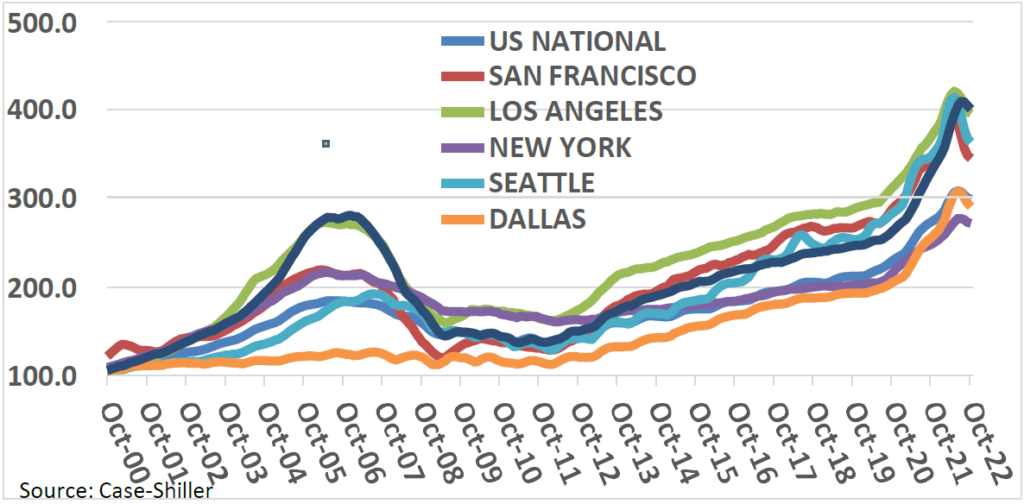

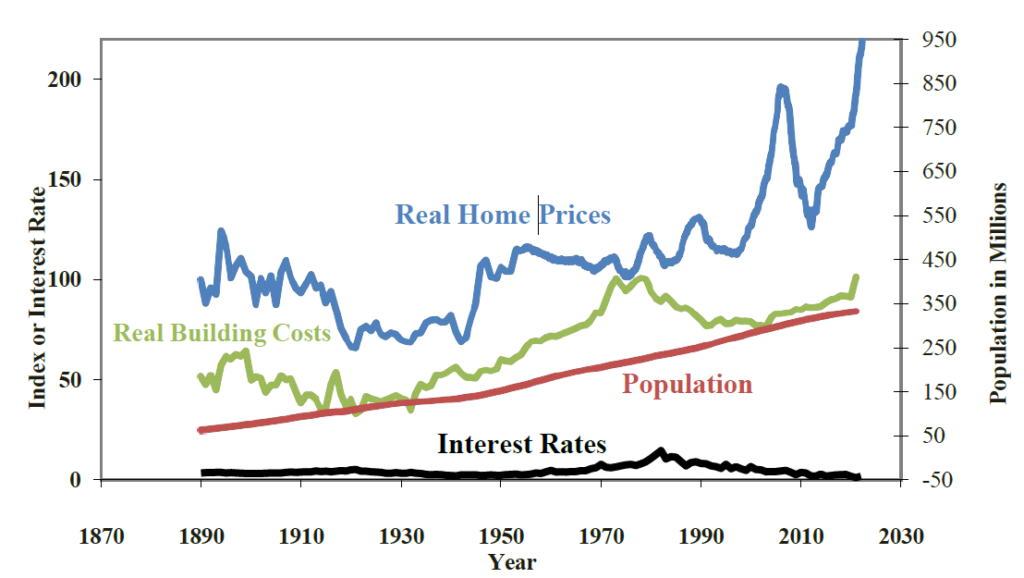

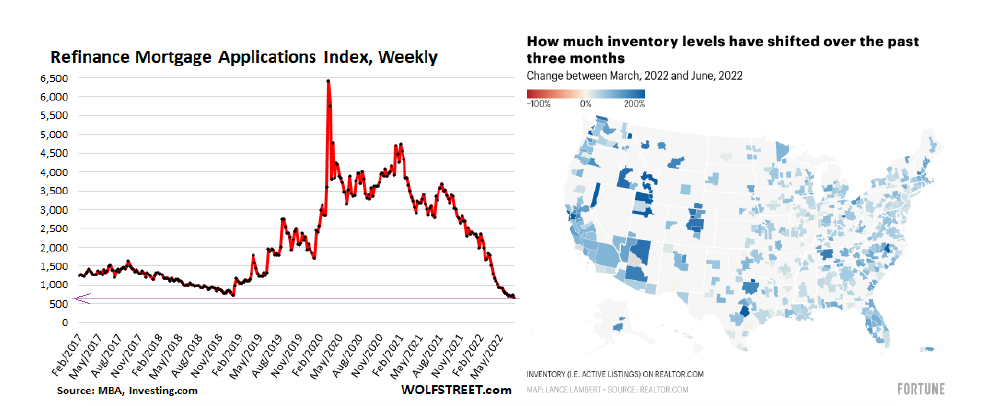

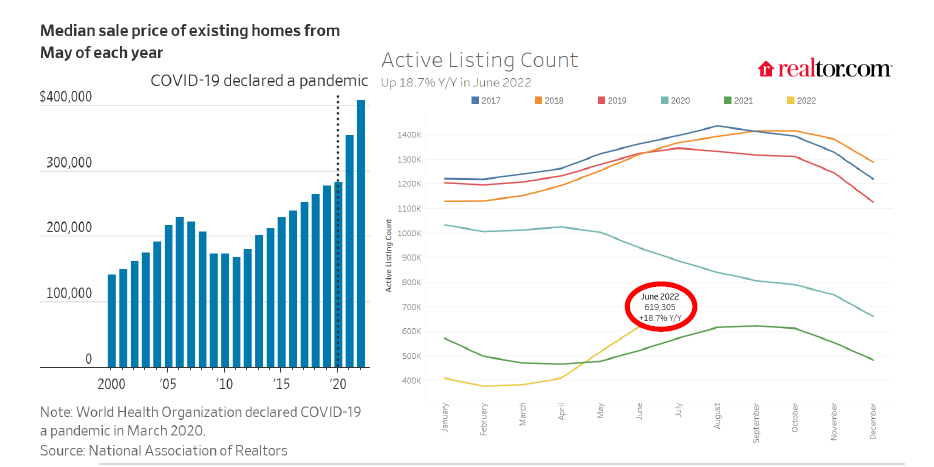

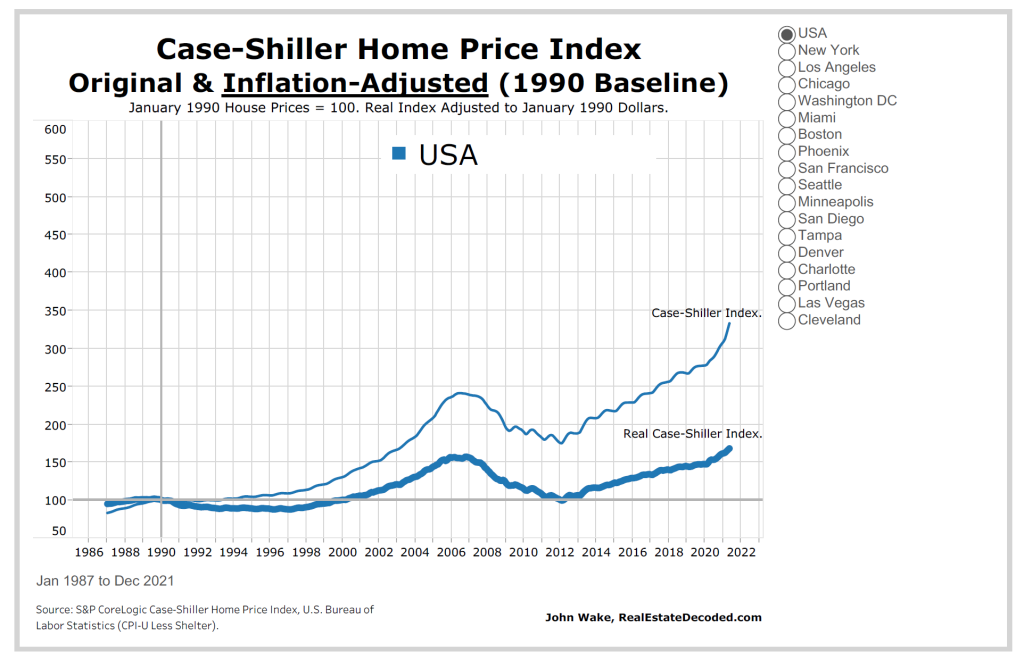

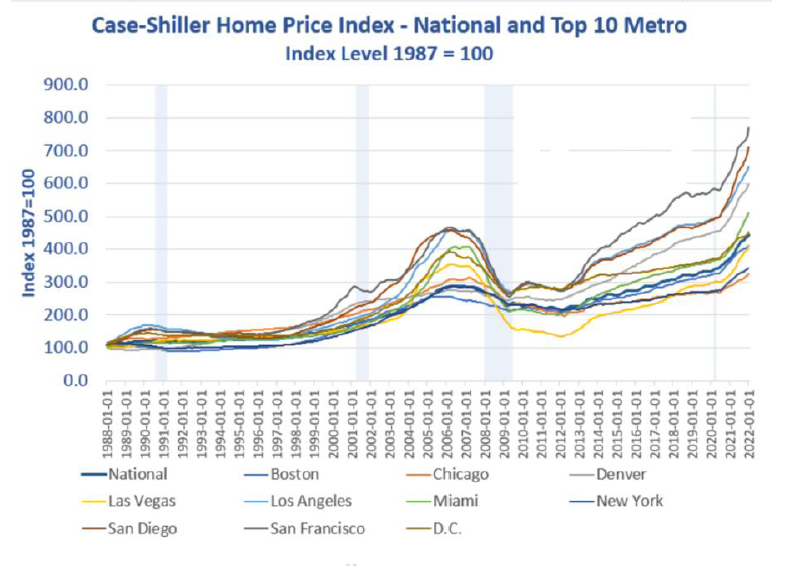

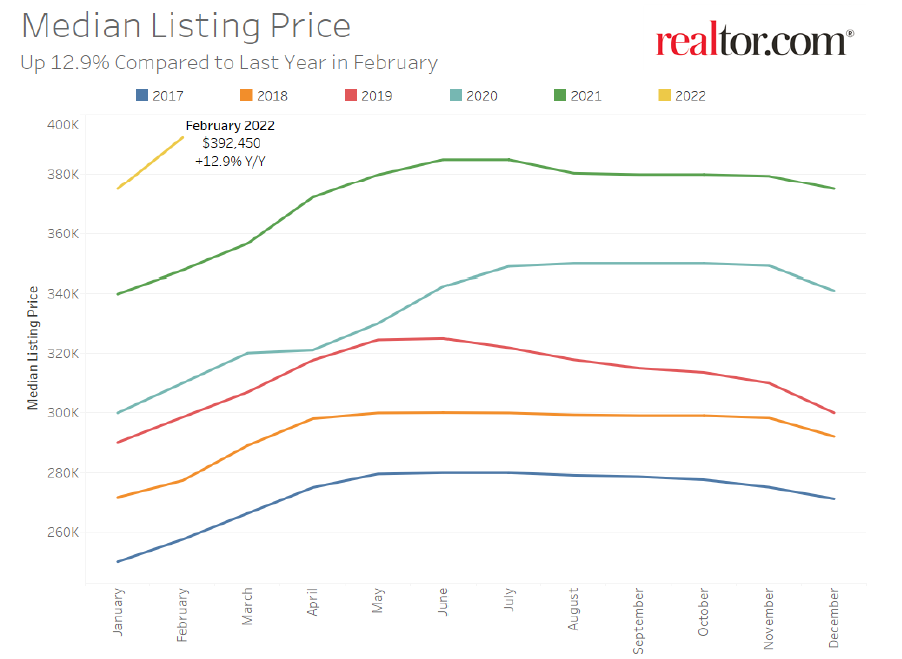

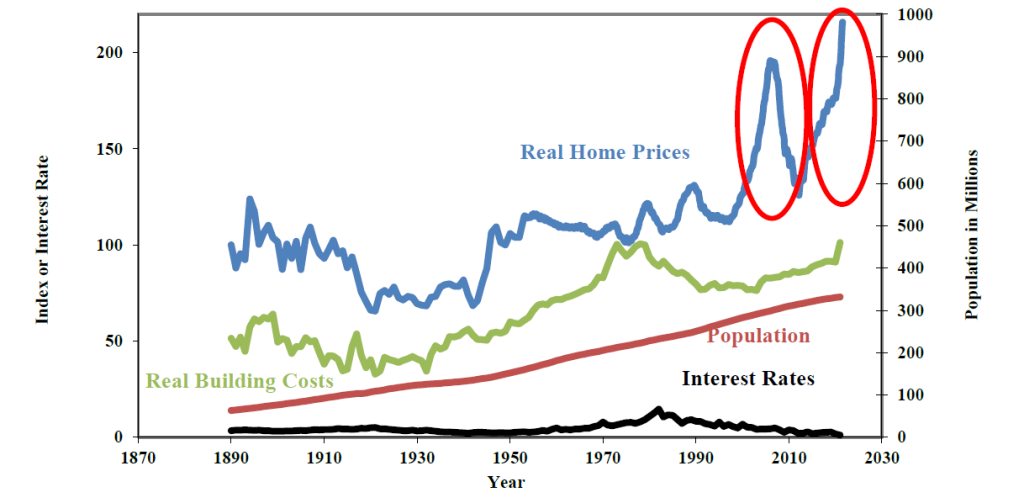

In a word, “resiliently,” with single-family prices up 2.0% nationally for the year ended April, representing 135 straight months of higher prices. That is not a typo. While individual markets may be struggling (e.g., Bay Area, Denver, Phoenix, Los Angeles), the overall market remains in decent shape and prices firm. Perplexed, the New York Times recently posed a rhetorical question in an article captioned, ‘What is Happening in the Housing Market?’ trying to explain how housing prices have not dropped despite the extraordinary increase in interest rates.

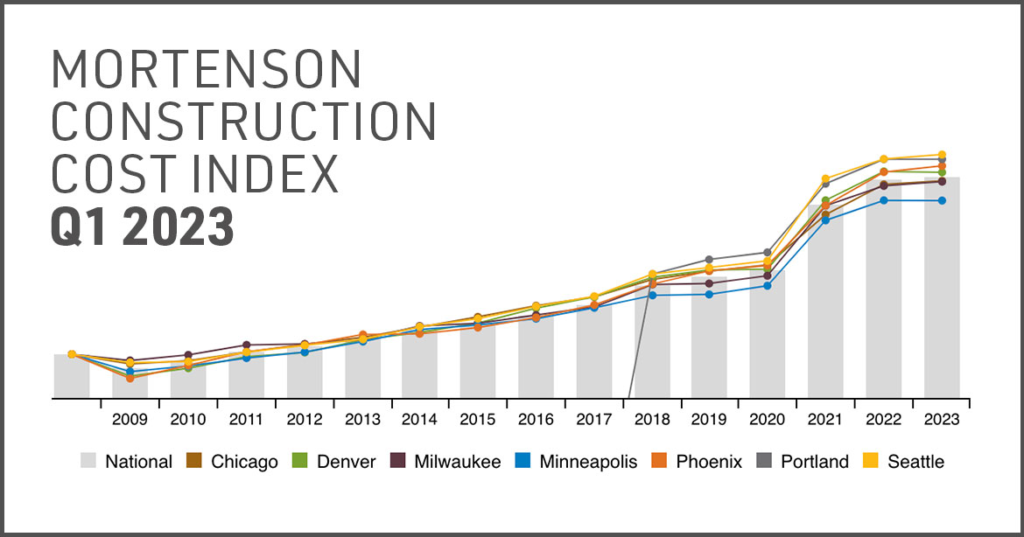

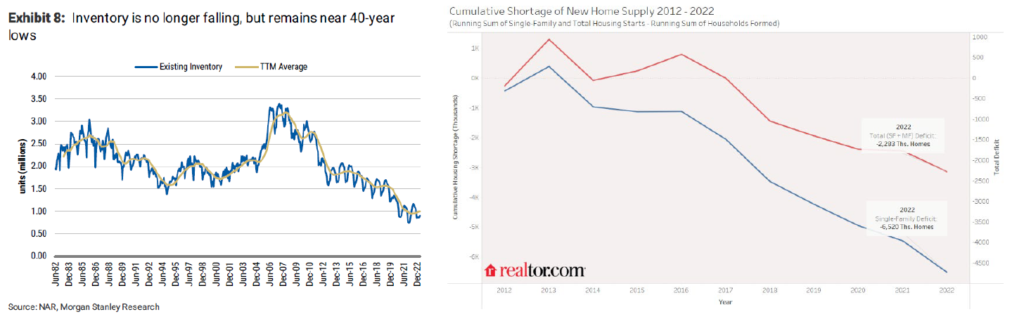

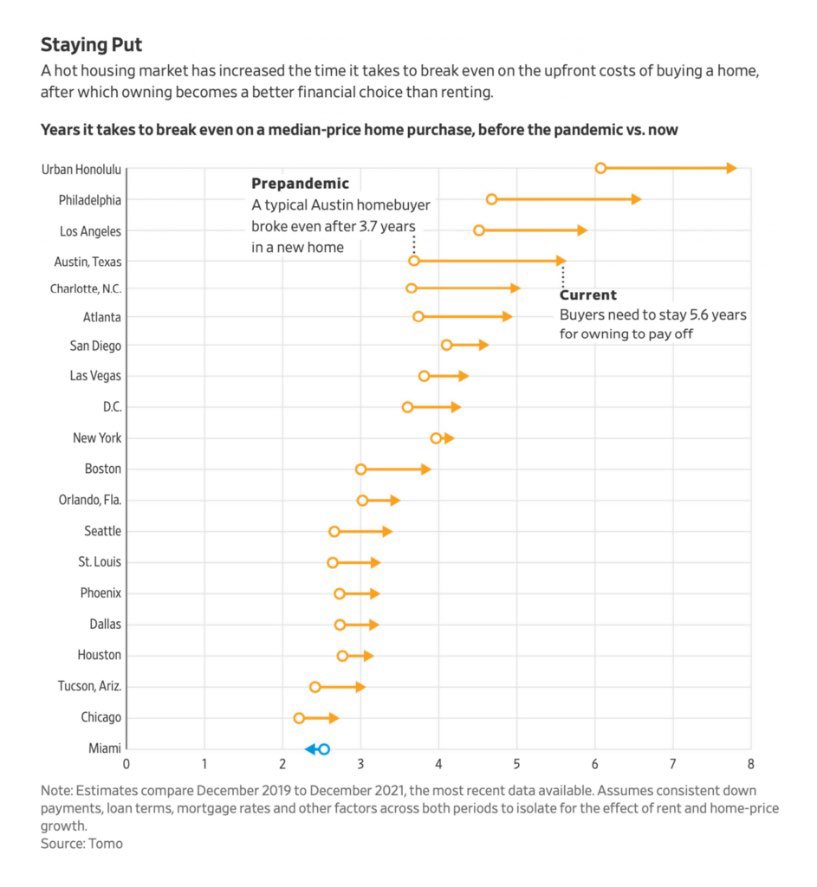

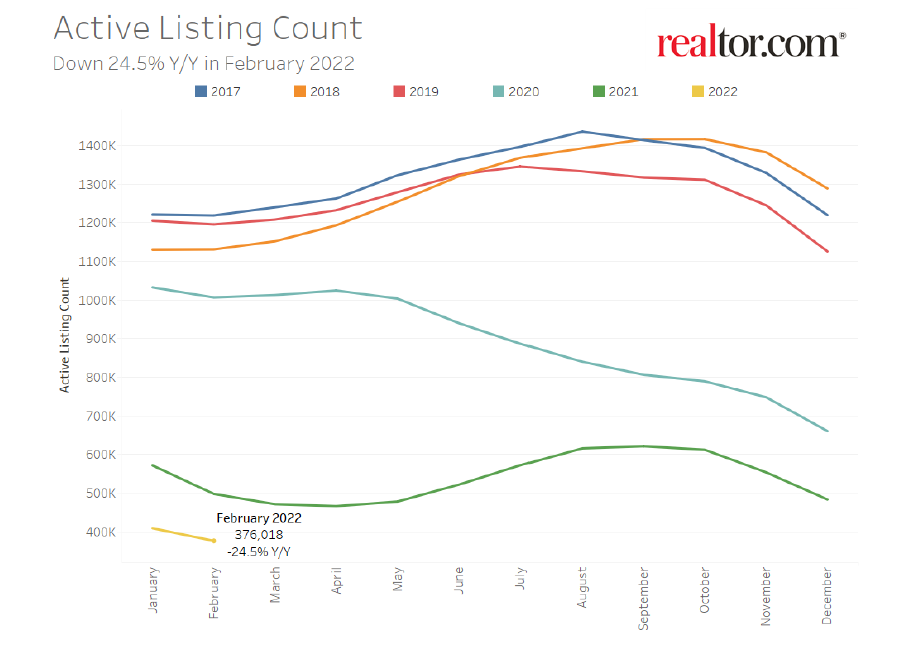

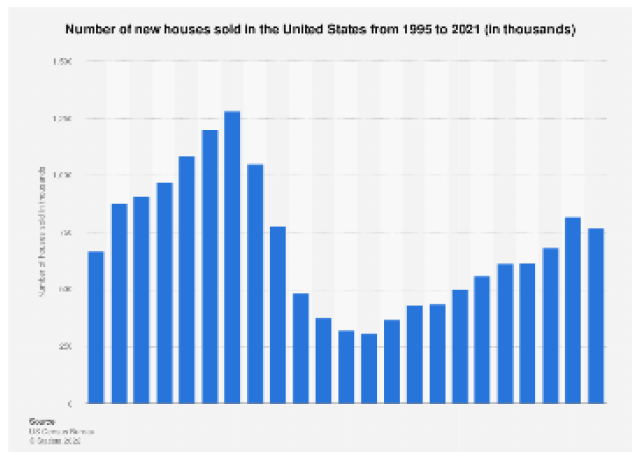

The answers are fairly simple. Record-low supply tops the list, as inventory hovers near 40-year lows. Baby boomers, with their trillions of equity in homes, ain’t selling. Folks who own or bought homes in recent years, with mortgage rates of 3.0% or less, ain’t selling. And builders can only build so many homes, with constraints on everything from buildable lots, available labor, raw materials, along with (of course) higher construction and borrowing costs, at least for smaller, privately-owned builders who cannot easily access the capital markets.

While more than 23,000 Alternative Dwelling Unit (ADU) or “Granny Flat” permits were issued in California last year (versus 5,000 in 2017), following the elimination of R-1 zoning in the state, the overall impact represents that proverbial drop in the bucket. The fact is that newly built homes represent about a third of all homes for sale in March, about double historical norms.

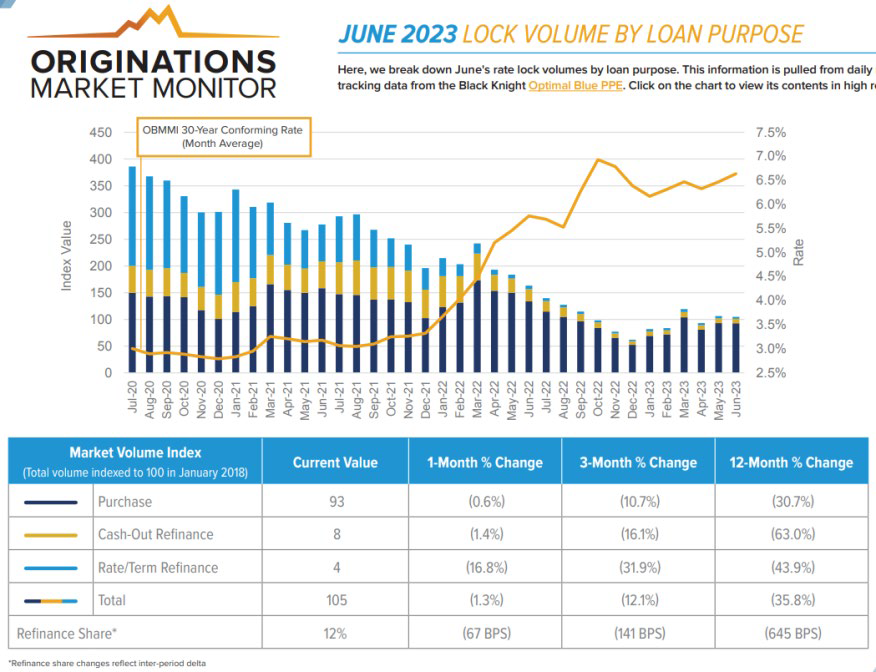

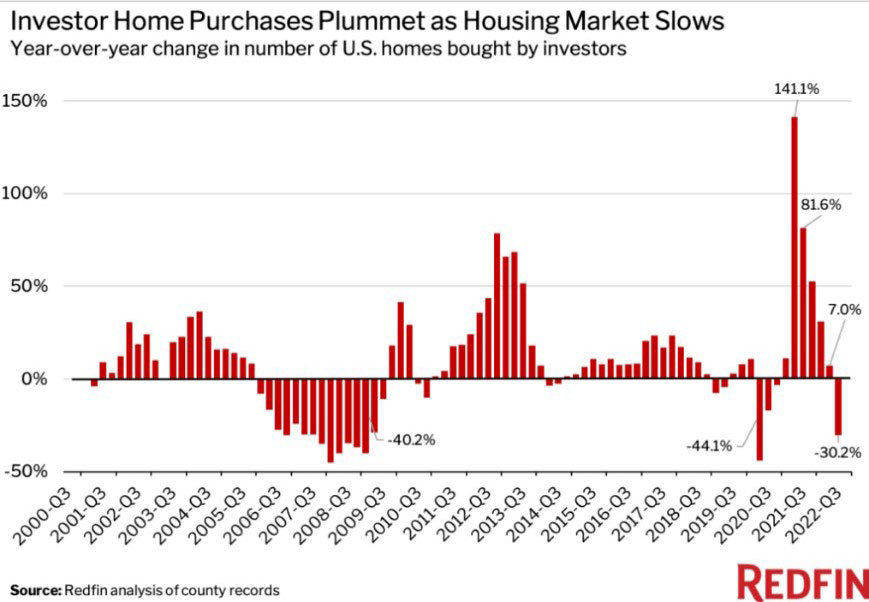

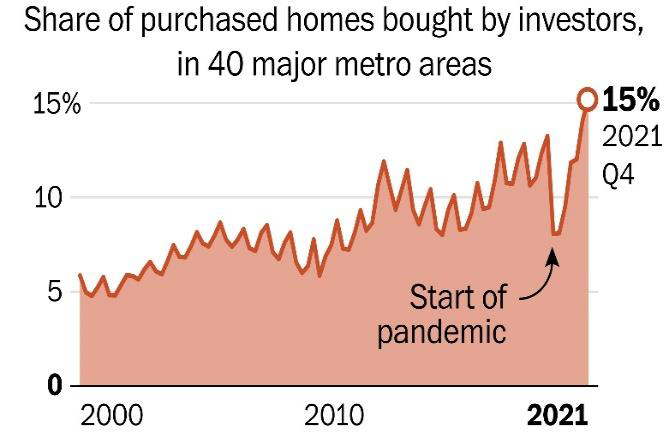

Some buyers, perhaps recognizing that waiting for a significant price drop in home prices is indeed akin to “waiting for Godot,” have decided not to wait any longer. Institutional and foreign buyers are also reliable sources of demand, albeit at reduced levels from previous years. In fact, while prices are firm, sales volumes are down sharply, as are mortgage applications.

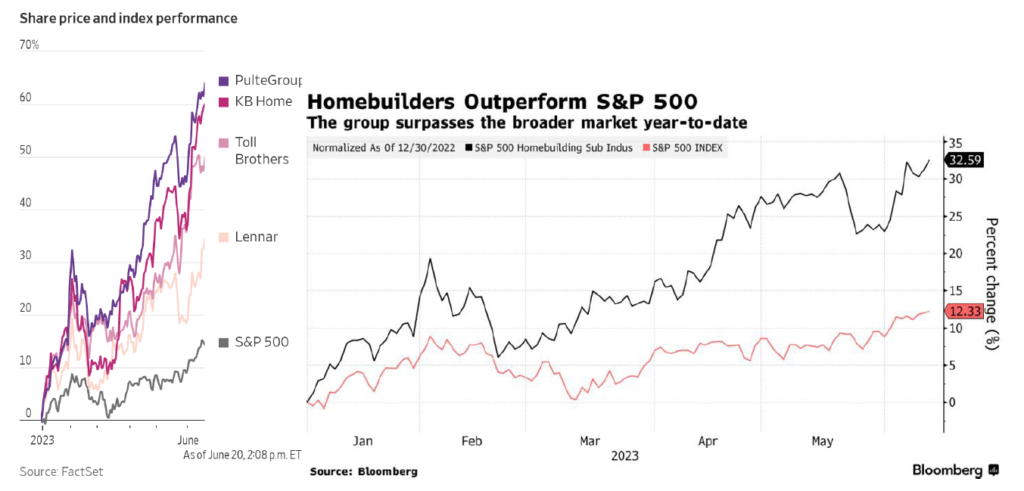

Meanwhile, homebuilders have been one of the hottest sectors in the equity markets thus far in 2023, defying all expectations and all the economic headwinds and higher rates. For example, KB Home is up over 24% this year and over 79% in the past 12 months, something I would never have predicted. Another “yowza” seems more than apropos. The entire homebuilding sector is up nearly 33% in 2023, more than double the return of the S&P 500. Yeah, those homebuilder stocks sure are boring. #sarcasm

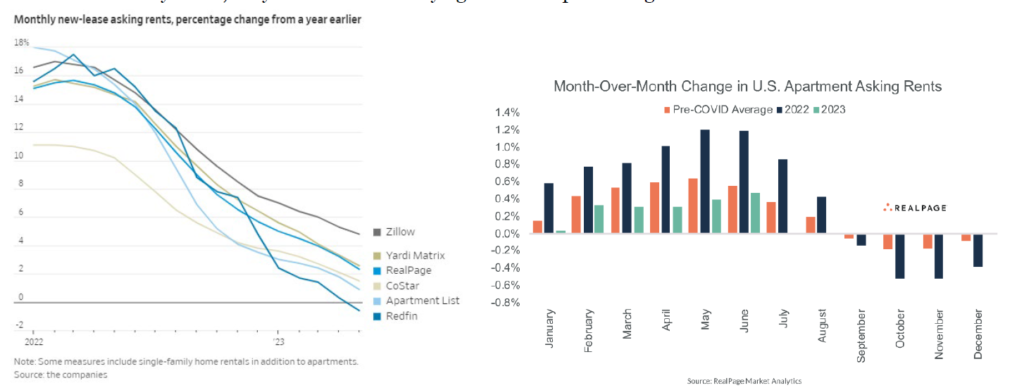

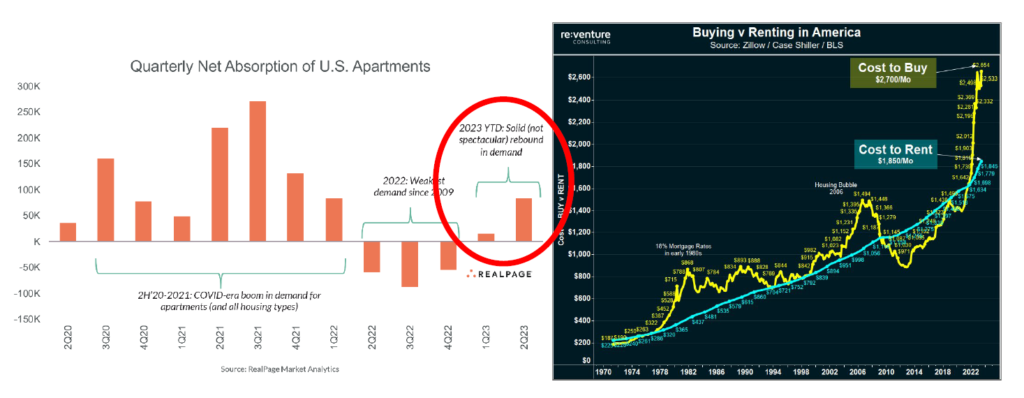

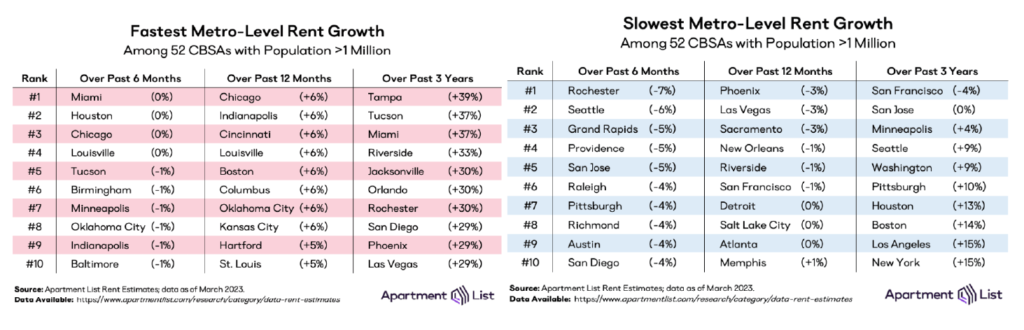

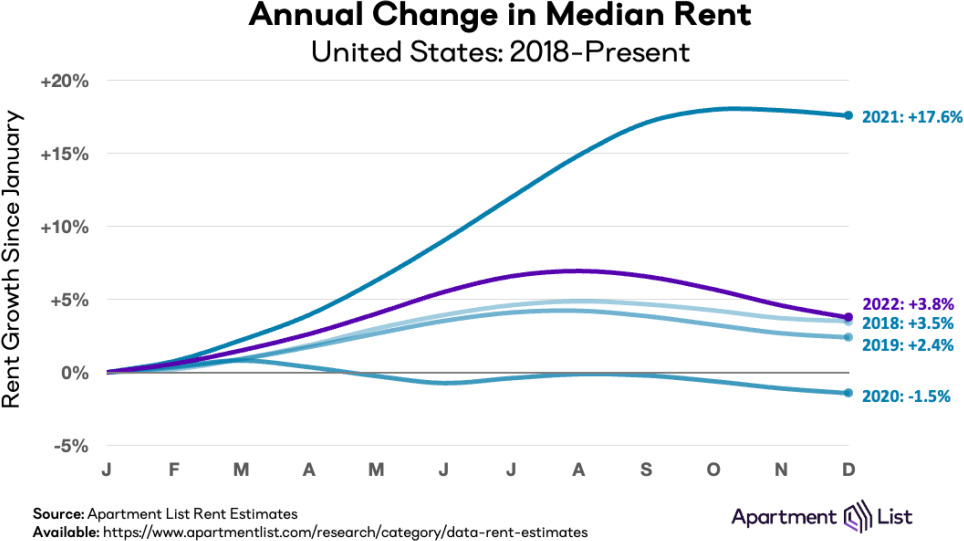

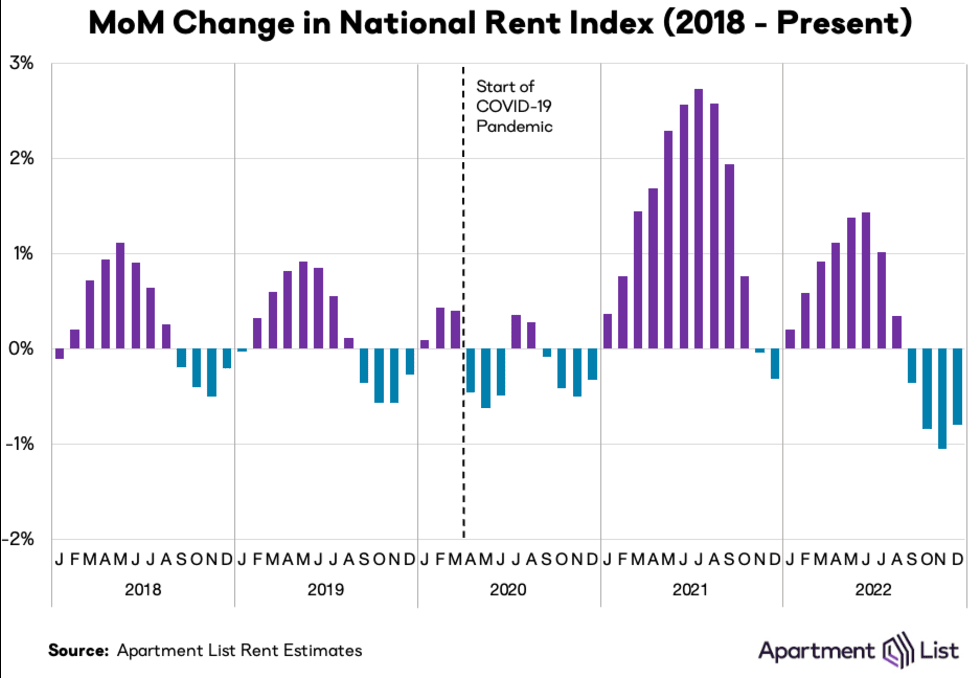

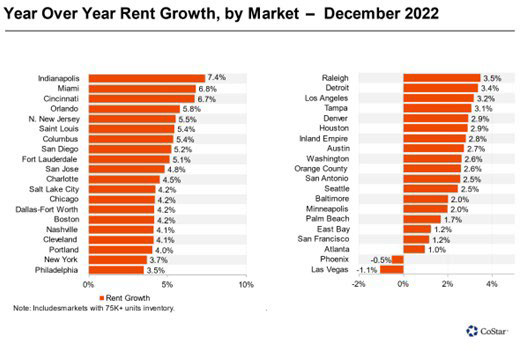

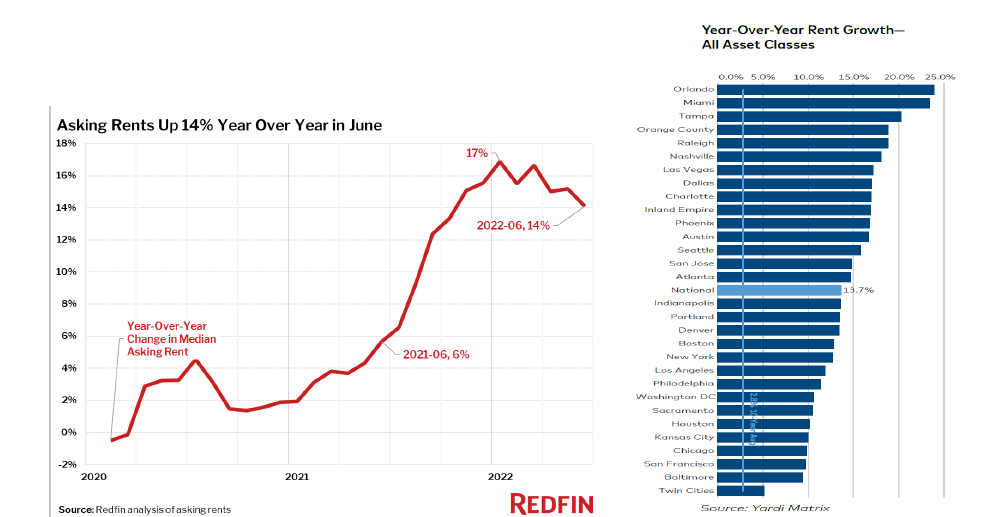

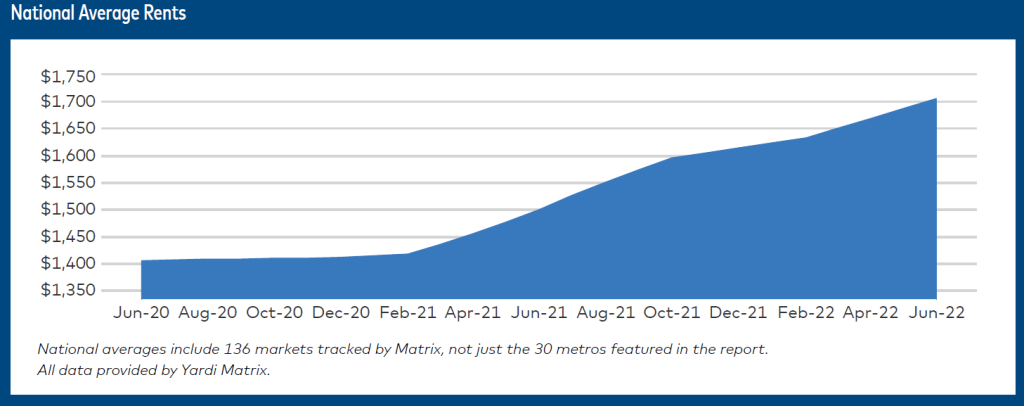

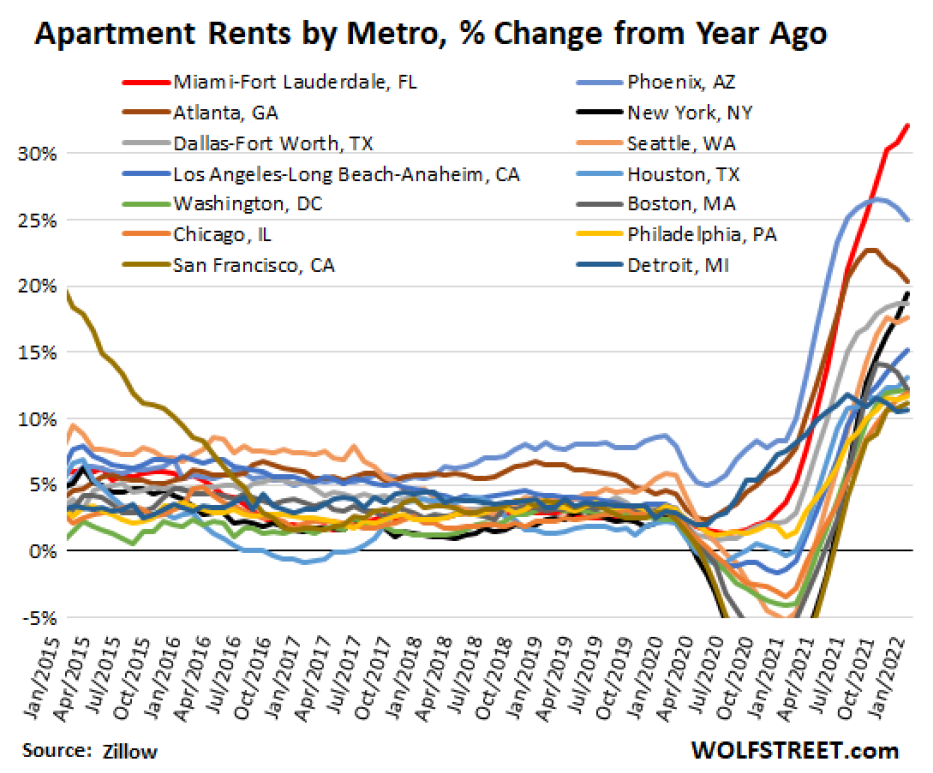

Ironically, the apartment market has not fared quite as well in recent months, as rent growth has stalled. The average of six national rental-price measures from rental-listing and property data companies indicates that asking rents for new leases rose just under 2% over the 12 months ending in May. One of the rent measures, courtesy of Redfin, indicates that rents for both apartments and single-family rental homes, actually declined 0.6% in May, year-over-year. A decline in asking rent over a 12-month period had only happened one other time since the Great Financial Crisis, when the rental market briefly declined in 2020 because of Covid-19, ending a decade-long streak of rent growth. However, while data providers agree on the direction of multifamily rents, they do not necessarily agree on the precise figures themselves.

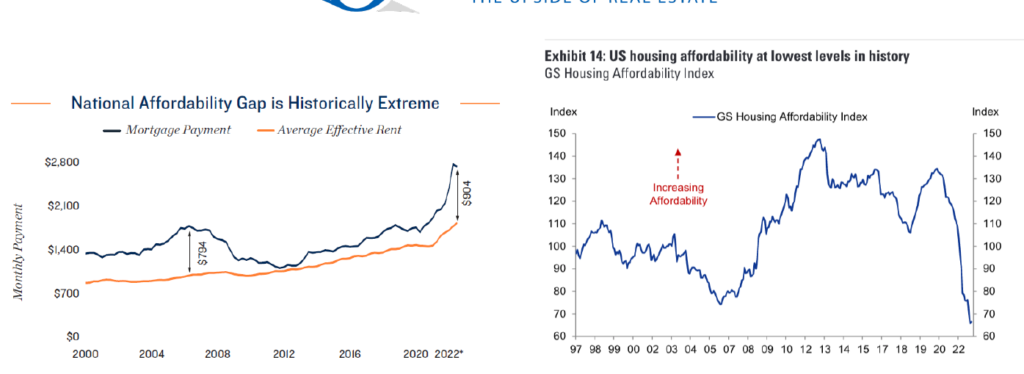

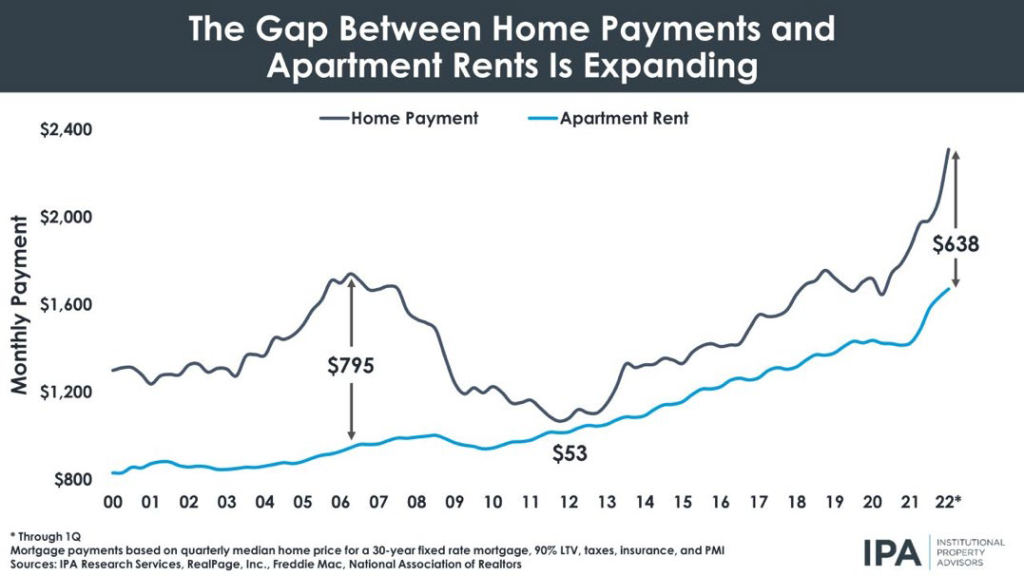

There are a couple of silver linings. One, absorption for multifamily units (excess of unit leasing activity above new supply) and demand are picking up. Two, affordability challenges continue to benefit apartments over single-family residences, making the renting decision more compelling. According to Realtor.com, the median home price in the U.S. was $445,000 in June, versus $441,000 in May. Combined with mortgage rates of around 7%, the monthly “cost to buy” is at least 40% higher than to rent.

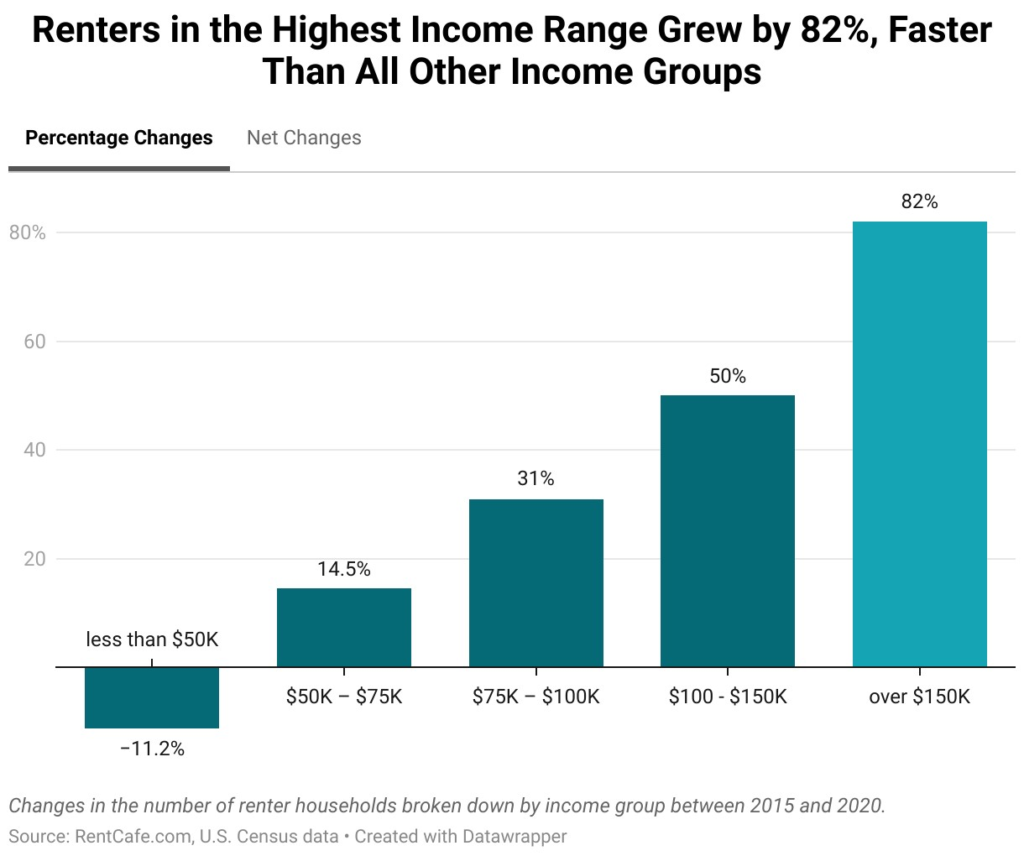

According to a number of articles I have recently read, higher income individuals and families are choosing to rent, perhaps also preferring the extensive amenities and flexibility provided by high-end multifamily units. Renters in the highest income range (household income over $150K per year) grew by over 80% between 2015 and 2020 (most recent data available), according to RentCafe.

Finally, the markets with the greatest net absorption during the first half of 2023 include Houston, Phoenix, Dallas/Fort Worth, Chicago, and Charlotte.

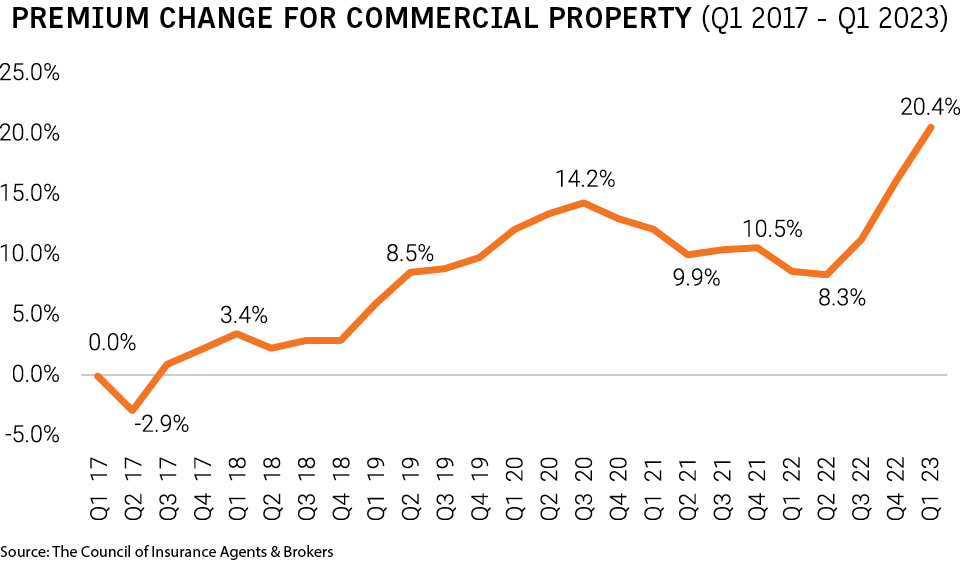

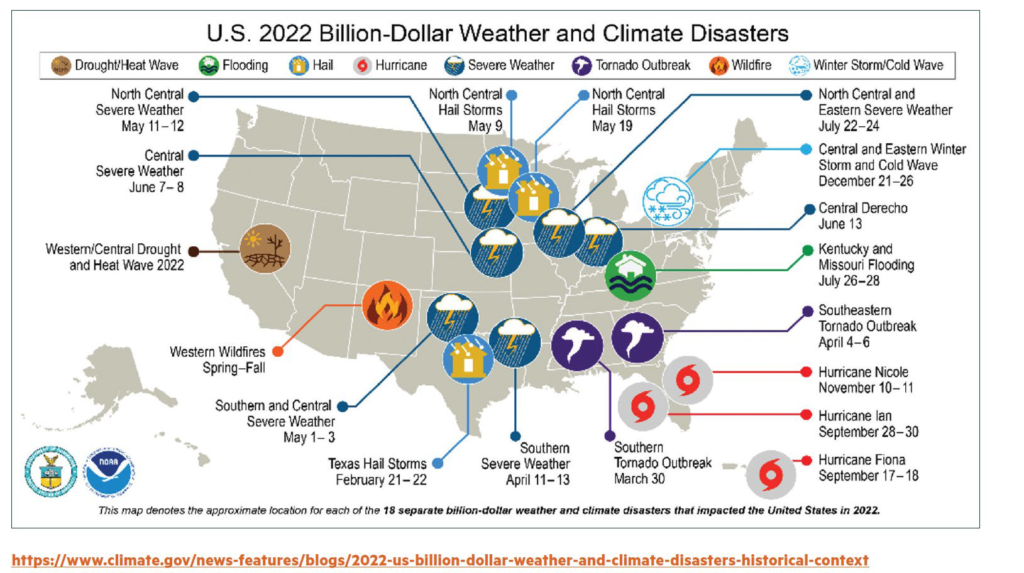

There is one other material issue impacting the residential housing markets, both single- and multifamily units, the escalating cost of property and casualty insurance…if you can even get it. You have probably read stories about how State Farm and Allstate are no longer writing new policies in California and Florida, as they grapple with increased claims from wildfires, hurricanes, and other weather/climate related issues. As you may know, Phoenix just recorded its nineteenth straight day of 110+ degree weather, a record, and July 2023 has thus far been the hottest month in history, at least since we have been measuring such things.

So, I suppose it cannot come as any significant surprise that the third quarter of 2022 marked the 20th consecutive quarter of increased premiums for commercial property/casualty, according to the latest report from the Council of Insurance Agents and Brokers. The average premium increase was up 20.4% in the first quarter of this year, again not a typo. To say insurers exiting certain markets and/or mercilessly increasing premiums are not impacting the residential housing market would be a profound understatement.

Perhaps a picture tells a thousand words…or a multitude of billion dollar claims.

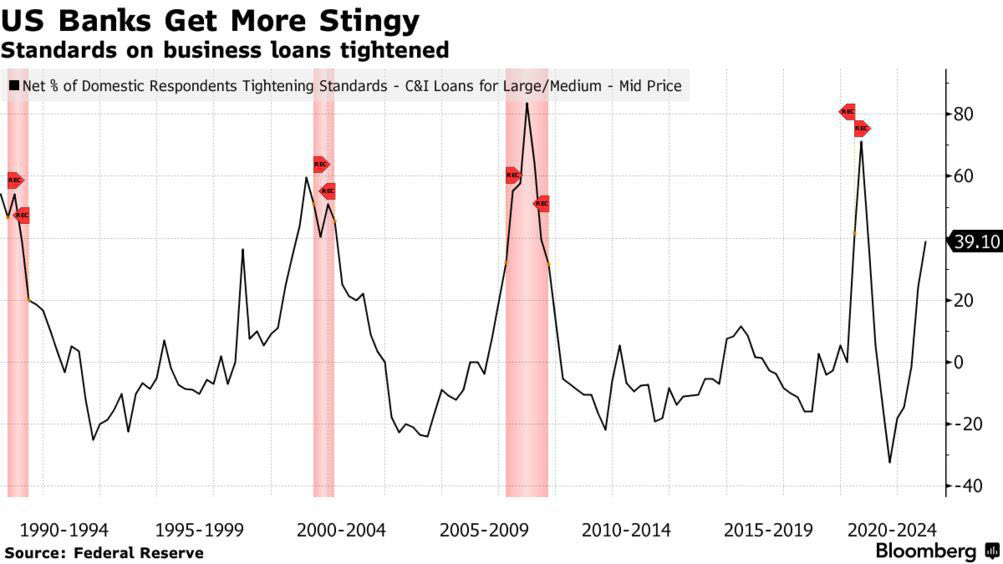

How are mortgage lenders and debt providers behaving in these volatile and uncertain markets?

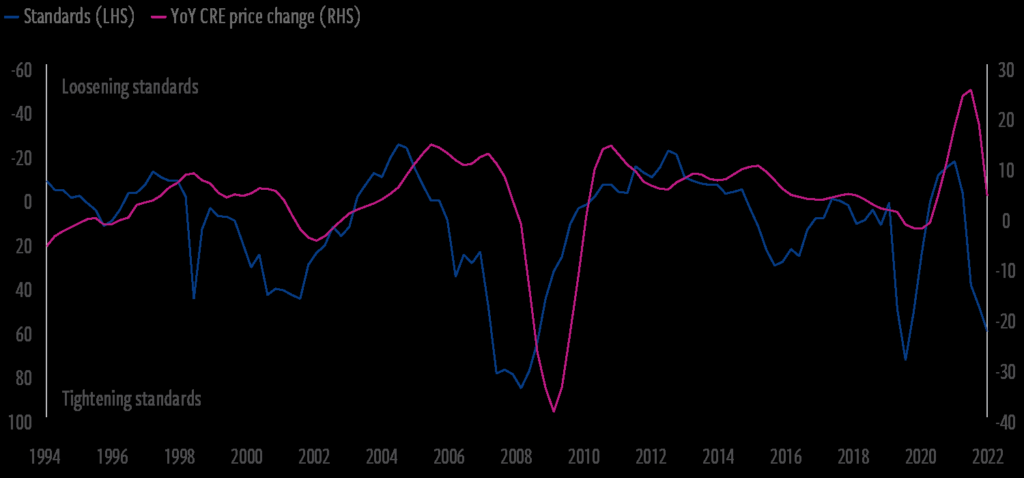

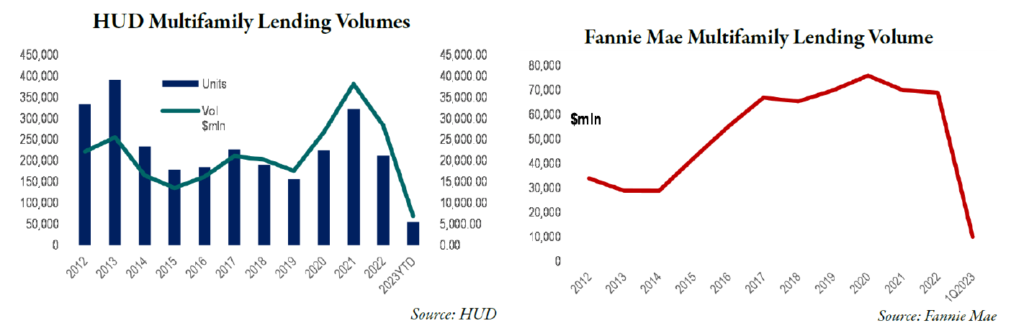

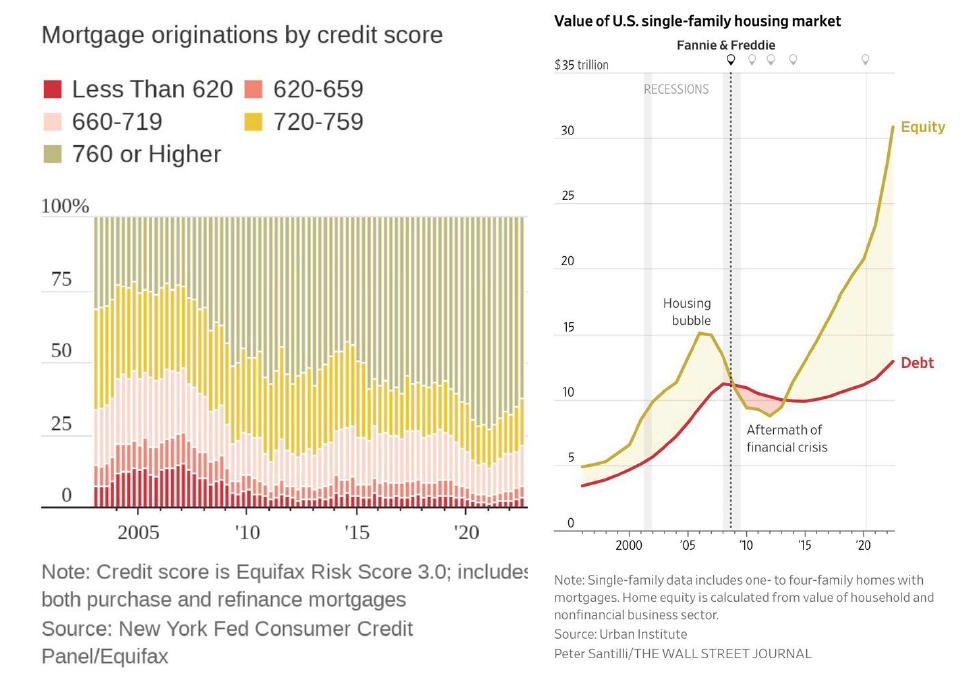

Even if a broader banking crisis and global credit crunch were averted following the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank, Signature Bank, First Republic, and Credit Suisse, prospective borrowers continue to be squeezed, not just from higher rates, but from stricter underwriting, higher spreads, and ultimately reduced proceeds. It is no surprise that multifamily lending volumes have tanked, reducing available liquidity, just when this source of capital is needed most.

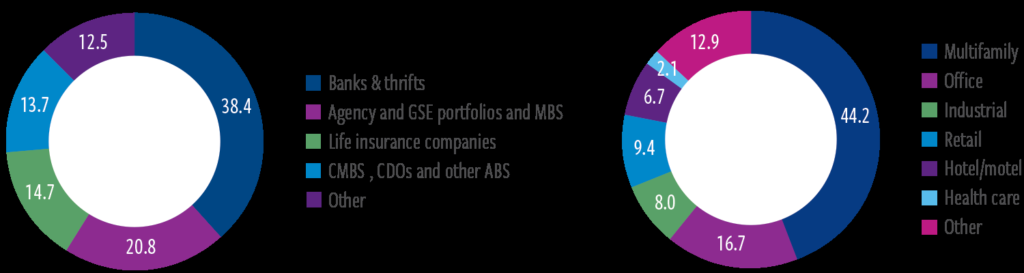

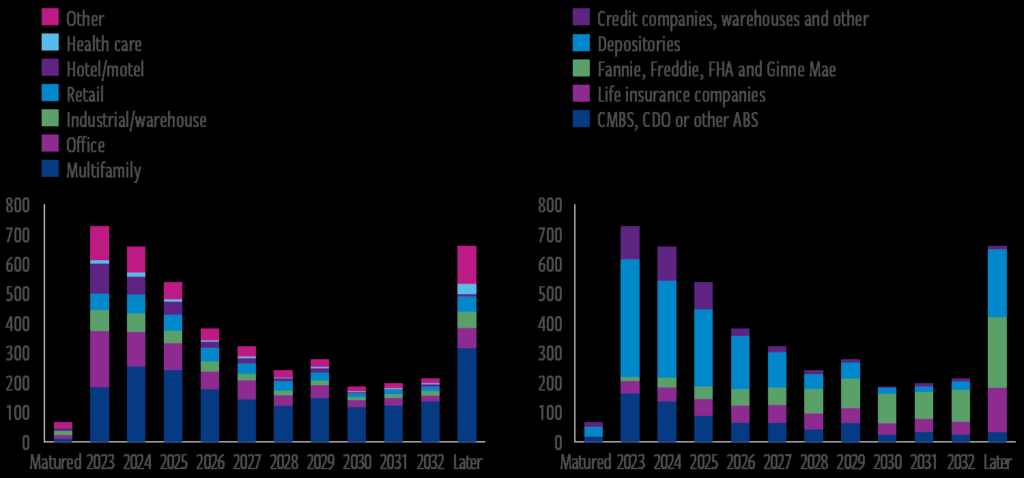

Keep in mind that there is approximately $20 trillion of commercial property in the U.S. (e.g., office, rental housing, industrial warehouses, and retail space) and all have been impacted by macroeconomic and geopolitical events. These assets are encumbered by some $4.5 trillion of collective mortgage debt, broken down as follows:

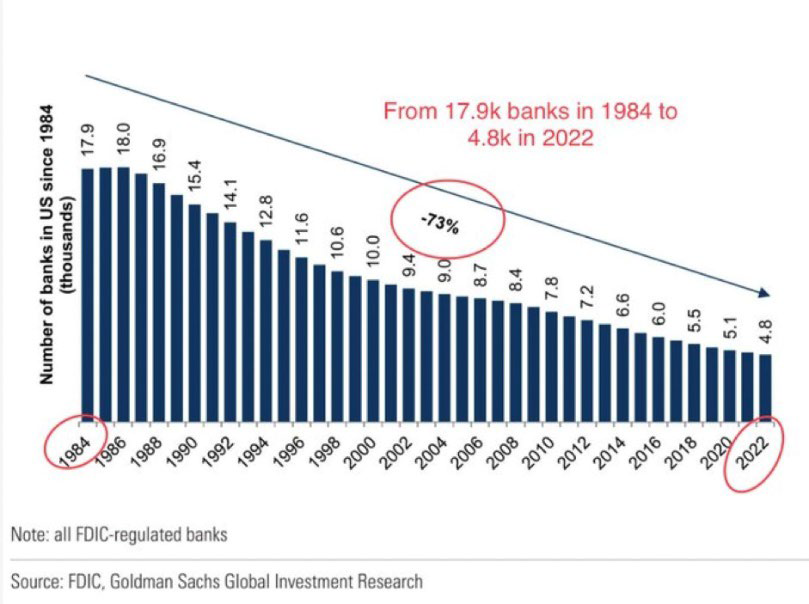

Meantime, the number of FDIC-regulated banks has declined precipitously (over 70%) since 1984.

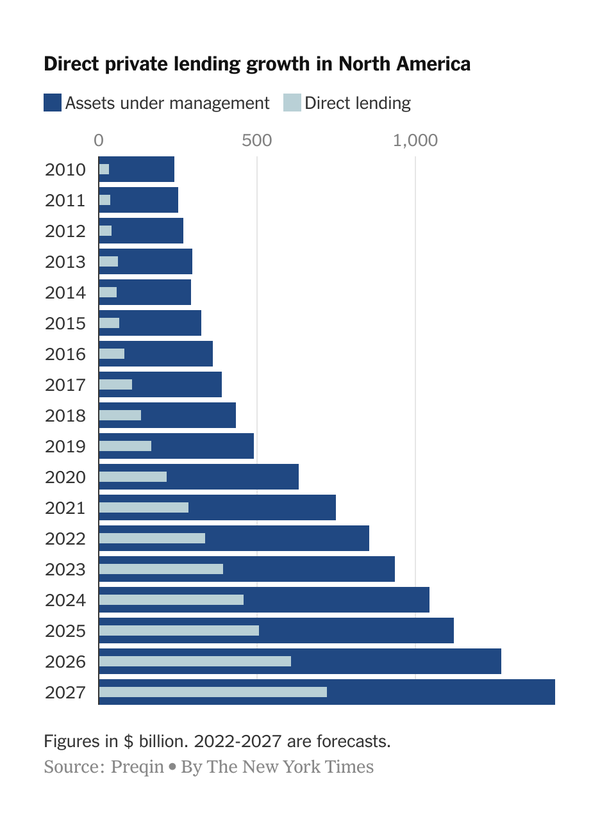

Thus, it is no surprise that the fastest-growing lending segment is “private credit,” or alternative lenders often referred to as “shadow banks.” Since the start of 2008, private credit has grown almost sixfold, to $1.5 trillion, according to the IMF—bigger than the high-yield bond or leveraged-loan markets. At $4.4 trillion, these three markets collectively exceed the value of all commercial and industrial loans provided by traditional banks, at $2.7 trillion. How these shadow banks and debt funds will respond to distress remains to be seen. My sense is that they have different objectives than traditional lenders, but whether that means they will be more or less flexible and willing to “extend and pretend” remains to be seen.

Finally, when are various commercial real estate loans coming due? The vast majority of loans come due between 2023 and 2025.

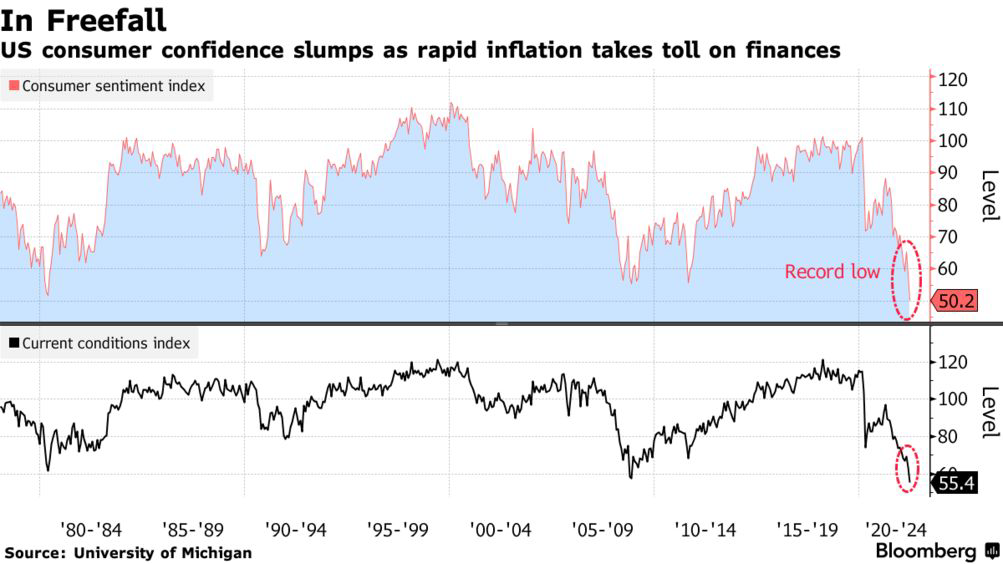

And consumers? Since they drive so much of the U.S. economy, how are they holding up?

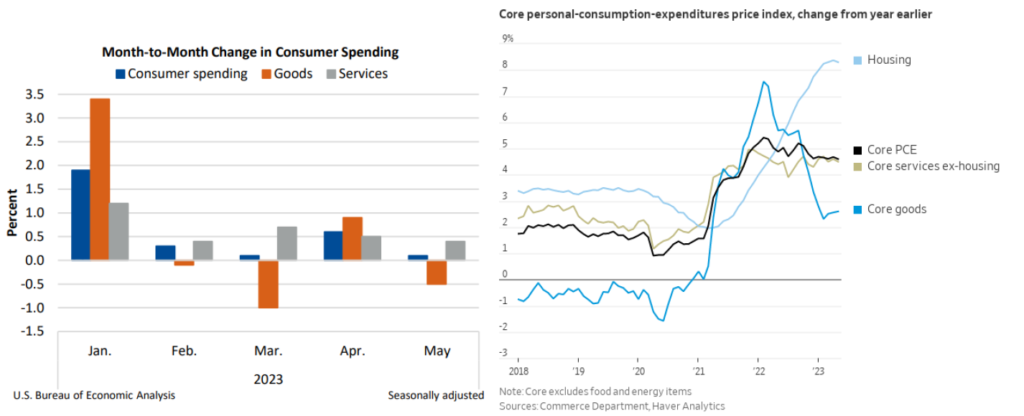

Consumer spending is also sending mixed signals. On the one hand, core personal spending remains positive, though monthly changes in spending have been declining. That is, it seems that the consumer is finally losing steam, at least from the looks of the data.

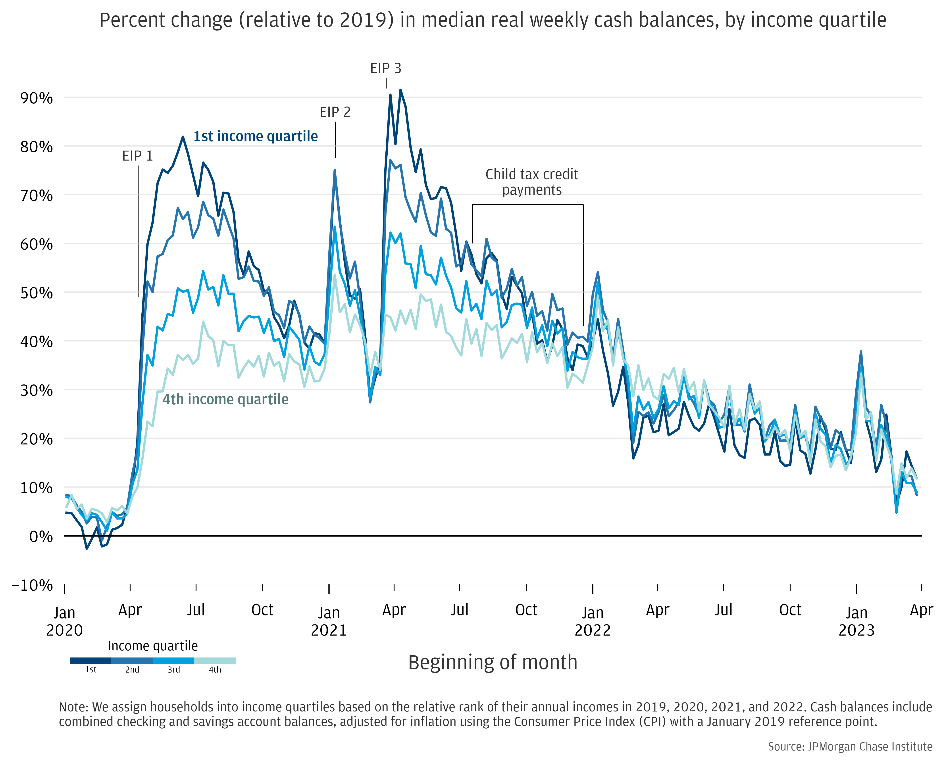

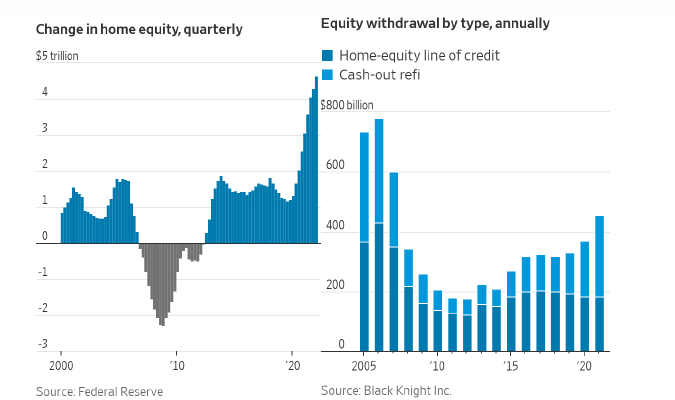

This is confirmed by the most recent data out of Las Vegas, where gaming revenues, one of the most discretionary of all expenditures, declined in both April (3.4%) and May (1.7%), the most recent data available, as compared with the same period last year. Perhaps softening consumer spending is not surprsing, as the cash savings accumulated during Covid, including the impact of government largesse (read: PPP loans) and lower residential mortgage payments (all those homeowners who refinanced in 2020 and 2021), have mostly run their course. Cash reserves are dwindling, with median account balances at their lowest levels in nearly three years, dropping some 41% from their April 2021 peak, according to JP Morgan.

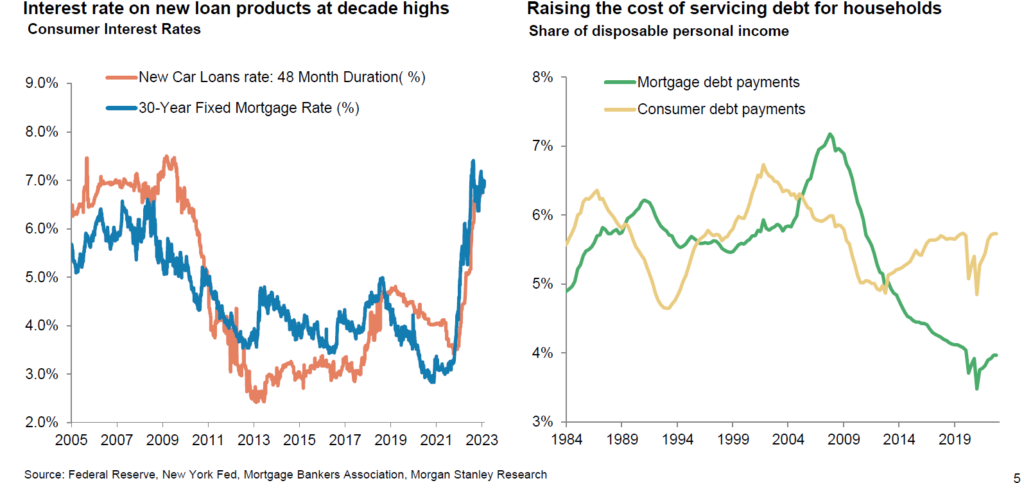

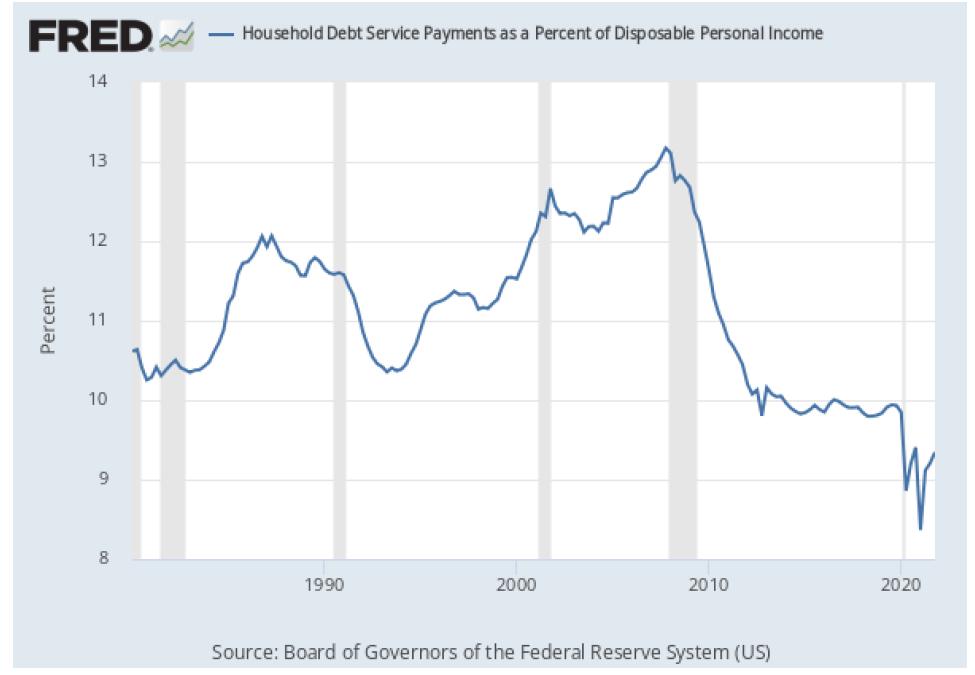

In addition, with higher interest rates on everything from new car loans to credit card debt to mortgages, consumers are feeling an incremental pinch.

On the other hand, having been on more than my fair share of planes in recent weeks, it seems that the consumer is not quite dead yet. Most flights are fairly full and I have to take extra steps to ensure that I don’t end up in that dreaded middle seat (yeah, flying coach is what it is). Data confirms my anecdotal observations, as North American air carrier’s traffic climbed 31% in May 2023 versus May 2022, while the load factor (% of occupied seats) rose 5.1% to 85.1%, the highest in the world. Globally, air traffic is now at 96.1% of May 2019 (B.C., Before Covid) levels, according to the International Air Transportation Association.

What have our wonderful politicians been up to policy wise in Q2, especially with such important local, state, and national elections teed up next year?

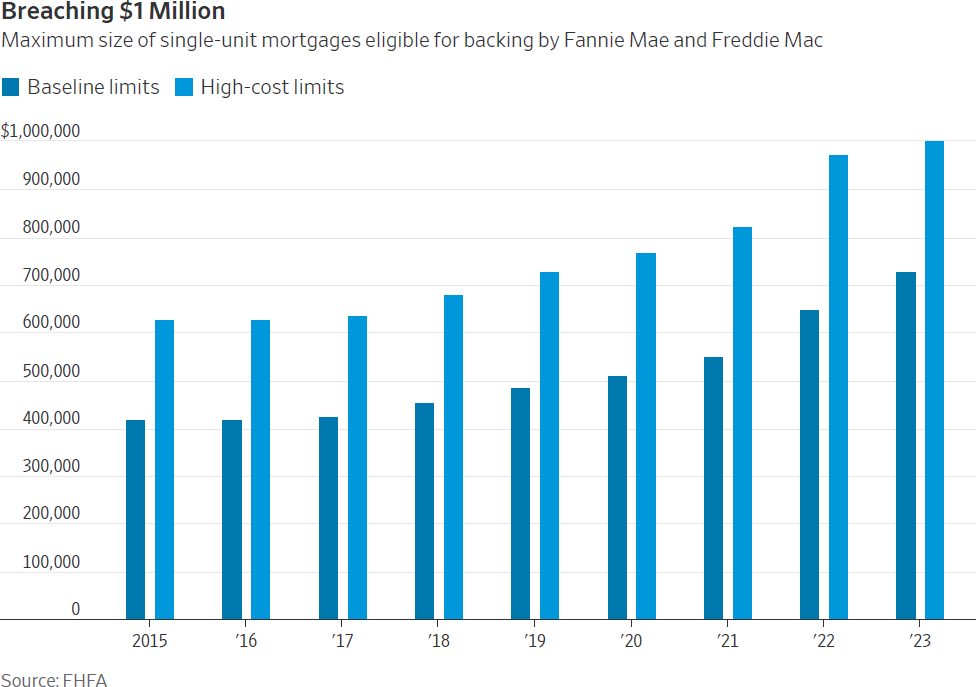

•Biden Administration’s New Mortgage Fees: Effective May 1st, new fees made their debut on already lengthy closing statements, as homebuyers with “strong credit” are being charged with higher fees by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, to subsidize borrowers with lesser credit. For example, a borrower with a FICO score of 700 and a 20% down payment previously would have paid an upfront fee of 1.25% of the loan amount, say $3,750 on a$300,000 mortgage. Now that fee has been increased to 1.375%. Generally speaking, lesser qualified borrowers will still pay higher fees, but the relative difference is lower. Presumably the objective is to make homeownership more affordable for lower-income borrowers, but I loathe these particular sorts of redistribution efforts, because I have always believed that the obsession with that “American Dream” of homeownership and specifically, that three-bedroom, two-bathroom, three garage home (gotta have room for the boat or Harley), is misguided.

•California Lawsuit Against Elk Grove: In early May, the State filed a lawsuit against the city of Elk Grove, in Sacramento County (near the state capitol), for denying a proposed66-unit affordable housing project. Meanwhile, the State exercised its political influence in getting San Francisco to approve three projects that had been subject to public opposition, including one 450-unit tower. Meanwhile, the State owns 7.6 million acres of property, including something like 58 million square feet of office space, much of which is under-utilized, if used at all. However, the sheer number of California’s 2023 Housing Related

Legislative endeavors are so voluminous that I can’t nearly summarize them all here. However, if you are so inclined, you can follow this link for a complete list and graphical summary, which looks like some of Picasso’s finest work. I just recommend that you fasten your seat belt and grab a glass of your favorite alcoholic beverage before doing so:

https://www.dropbox.com/s/6cnpm11spdoqc2x/CA-housing-bills-20230611.pdf?dl=0

•Montana Legislation Limiting Local Governments from Implementing Rent Restrictions: On the other hand, in May, Montana became the 33rd state to pass legislation limiting local governments from trying to implement rent restrictions, coming on the heels of similar legislation passed in Florida at the end of March and Ohio last June. Of course, other states, from California (of course), Maine, Maryland, Minnesota, New Jersey, and New York are behaving quite differently. According to the National Apartment Association, there are eighty-three state bills out there that would regulate rents. But bills do not legislation make, so we shall see, but I have warned of this inevitability for years. Politicians will do tenant bidding, so long as there are more tenants than landlords who vote.

And finally, what else has been going on in this wacky world that may impact commercial real estate?

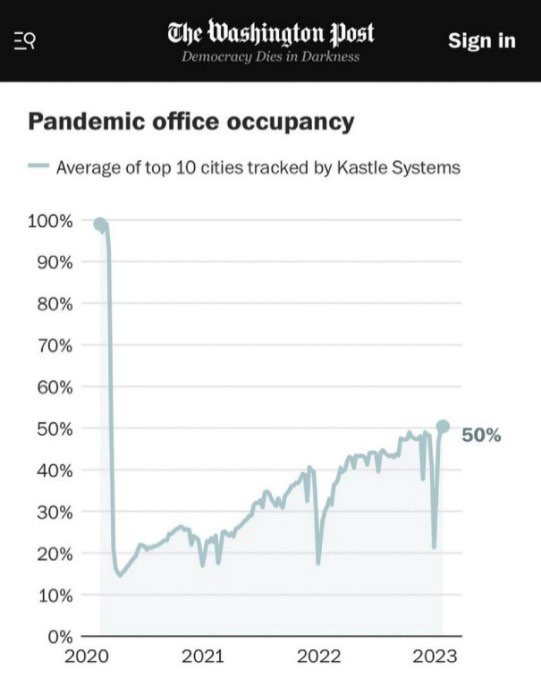

•Commercial (office and retail) property woes continue, surprising nobody: Changes in work and shopping habits continue to wreak havoc on related property markets. UBS estimates that around 50,000 retail stores will close in the U.S. in the next five years. Bed, Bath, and Beyond will shutter about five hundred locations in total. The value of malls is down 19% in the past year and 44% since 2016. And the office horror story is well known, with values down 25% or more across the board, with occupied space per worker down 12%from 2015. Regarding specific submarkets, Chicago saw a jump in office sublease availability jump 7.7 million square feet in the first quarter, which pales in comparison to San Francisco’s 8.9 million square feet, a 140.5 percent increase since 2020. The Los Angeles office vacancy rate reached 22.5%, a historic high, while the vacancy rate increased to 17.1percent, up from 16.9% at the end of 2022. The percentage of Washington D.C.’s office market that is available for lease jumped to 21.7%.

•Student Loan forgiveness: In mid-2020, during the throes of the Covid pandemic, the federal government suspended required payments on nearly $1 trillion of student loans. The moratorium was meant to last six months (or roughly the length of a Kardashian marriage),but like so many government policies, it lasted far longer than intended. The moratorium was extended eight times, of course, which is comical. Don’t get me wrong. I fully understand the argument that the government has a history of forgiving debt (e.g., PPP loans) and bailing out corporations, the old “what’s good for the goose is good for the gander” argument, though I don’t necessarily subscribe to it.

In any event, student loan payments recommence in September, at long last, which will curbsome consumer spending, at least on the margin. In addition, the Supreme Court recentlyruled that President Biden did not have the unilateral authority to forgive some $400 billionin student loans without congressional approval. In response, the Administration announcedthat it will forgive $39 billion of such loans under a different, income-driven proposal, whichwill more likely pass muster and judicial review. We shall see. The important takeaway isthat many consumers will be required to service debts with funds they were previously ableto spend on other goods and/or services…including rent (presumably).

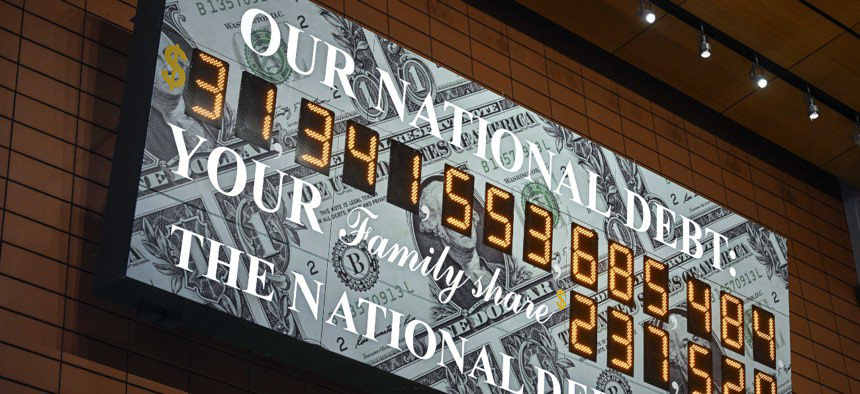

•Deficits and Debt Ceiling Negotiations: I am not sure if you have ever seen the billboard-sized display on Sixth Avenue between 42nd and 43rd Streets in midtown Manhattan, which provides a running total of our nation’s gross outstanding debt and each American family’s share of it. I am also not sure it quite compares with Lady Liberty, the Empire State Building, or Grand Central Station in terms of tourist attractions, but you certainly can’t miss it if you happen to stumble upon it. Anyhow, when this unusual “clock” made its debut in 1989, our debt approximated $3 trillion. Here is a more recent picture, sobering as it might be. You will note that the clock still begins with a “3,” but there are more digits after that:

I mention this in the context of both the recently completed debt ceiling negotiations, which can charitably be labeled a “_hitshow,” as the agreement to raise the ceiling by $4 trillion merely allows us to borrow enough to pay existing obligations and fund government operations for the next two years. So, let’s dispel some misconceptions right off of the bat. One, the negotiations and accompanying agreed-to spending cuts do virtually nothing to balance the budget. Sure, it will cut spending by some $1.5 trillion over the next decade, but the agreement doesn’t lay a hand on areas of real spending: Social Security, Medicare, and defense, three outflows that collectively represent nearly 80% of our annual federal budget. And there’s the rub.

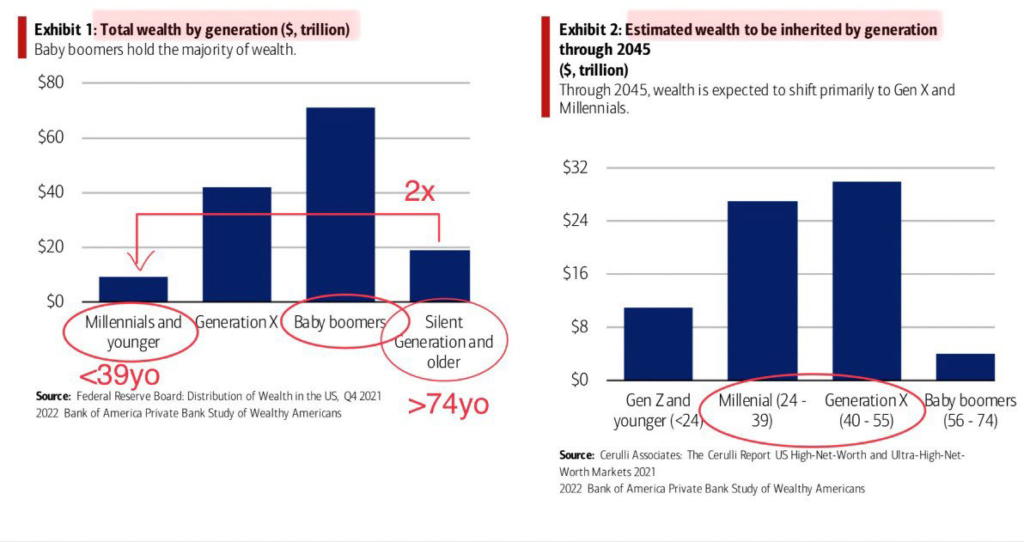

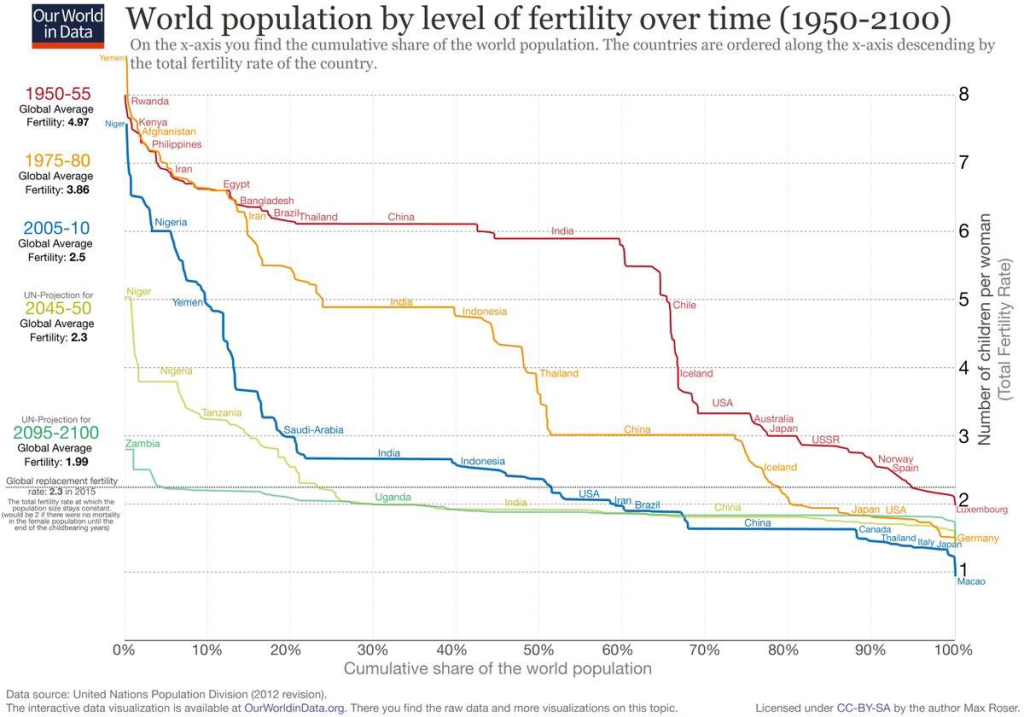

While I appreciate the political sensitivity to making cuts (or significant changes) to these programs, I don’t see any way that we can’t, at least without substantially raising taxes. We spend six times more per senior than per child, trading off social security benefits and education, but let’s be clear. That tradeoff simply isn’t sustainable as the costs of entitlements increase, our population ages (I have written a lot about that in prior letters, our so-called “baby bust”), we have fewer younger workers, and the government collects far less taxes. Tax collections have predictably fallen, following the passage of the 2017 Tax Cuts Job Act (TCJA). At some point, our politicians on both sides of the aisle are going to have to face the music, sacrificing politics for national fiscal security.

Figures from the Congressional Budget Office, which coincidentally don’t anticipate recessions, crises, or understated required infrastructure investments (think conversion of auto industry to electric), tell just a part of the story. In any event, I find the graph below to be just a tad frightening, perhaps even more than most driver’s license and high school yearbook photos.

Something has to give, as the gap between revenues and outlays widens over time, mainly because of rising interest costs and growth in Medicare and Social Security spending, resulting in ever-widening budget deficits. After World Wars I and II, we repaid debt by raising taxes and cutting expenditures. Compare that to today’s mindset, which seems completely different, and both parties to blame, of course. Even before Covid, in an economy characterized by record high stock prices, strong housing and commercial real estate markets, and low unemployment and inflation, we still ran a deficit, in part due to the TCJA. In any event, if the federal government does ultimately decide to face the music, raise taxes, and reduce spending, the impact should be materially deflationary, all else equal.

•Artificial Intelligence (AI) and real estate: Unless you have been living under that proverbial rock (and if you have, I sure hope it isn’t in Phoenix), 2023 might be labeled “The Year When AI Became Mainstream,” with the release (or at least popularization) of ChatGPT. At this point, it is hard to say how AI will impact commercial real estate, but you can bet your bottom dollar (or your favorite cryptocurrency) that it will be impactful in the following areas:

-Location, location, location: AI companies and related jobs and infrastructure investment will cluster around established tech markets, universities, and innovation centers.

-Increased demand for certain types of assets: AI research and development will require more and perhaps distinct types of data centers, energy grids and related infrastructure.

-New asset and product types: The AI transition will spur the development of new types of commercial properties, or at a minimum, significant investment in existing product types (e.g., office, industrial) just to make them AI-compliant. Think about the last time you saw an individual staffing a parking kiosk. Smart cameras and related security systems will replace uniformed officers. Or consider how hotel lobbies will change as the need for in-person interactions (e.g., check-in, check-out, concierge services) changes.

-New/Changed underwriting processes: AI-will substantially automate underwriting and the understanding and analysis of markets and individual properties. Individual acquisition personnel will still be needed, if just to exercise judgment and interpret data, but I suspect investors and sponsors will require less human engagement in the underwriting process.

-Design and space function: AI will allow engineers, architects, and other related professionals to more efficiently and quickly design and customize spaces and settings.

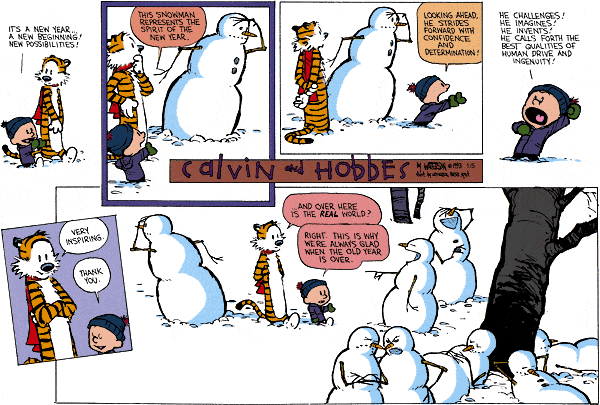

In my career, I cannot recall a market with so much conflicting data, adding to investor uncertainty and making predictions no easy task. However, while challenges lay ahead, crises and down cycles inevitably provide opportunities.

If one were to watch the news (or media outlets that hold themselves out as such), pay attention to certain polling, or read your weather app, you might think the sky is falling, the planet melting, and a recession around the corner. In fact, according to a recent Wall Street Journal poll, a large majority (78%) of individuals polled “do not feel confident” that their children will be better off than they were, the highest percentage since the survey began in 1990.

With all the negativity emanating from everyone from politicians to media outlets to my mother-in-law, such pessimism is understanding. Interest rates remain high and volatile, and while recent inflation data looks promising, it is too early to declare victory. Consumers will be more stretched and challenged in coming months, as cash reserves dwindle, student loan repayments resume, and the cost of consumer debt remains high. The disruptive potential of AI and negative psychological influence of social media only add to the understandable angst. And commercial real estate investors, capital providers, and all other industry participants are going to be busy working through a longer trough of this particular downcycle. There is no escaping this reality.

However, from GDP figures to employment levels to real wages to corporate profits and equity markets, it appears that a recession is not in the cards, at least for the time being. However, that could change quickly if the Fed continues to wield the interest rate sledgehammer, causing additional disruption to investors, lenders, and capital markets, generally. But let’s be clear. Our economy has done and is doing pretty darn well, all things considered, especially relative to the rest of the world, despite news and rhetoric to the contrary.

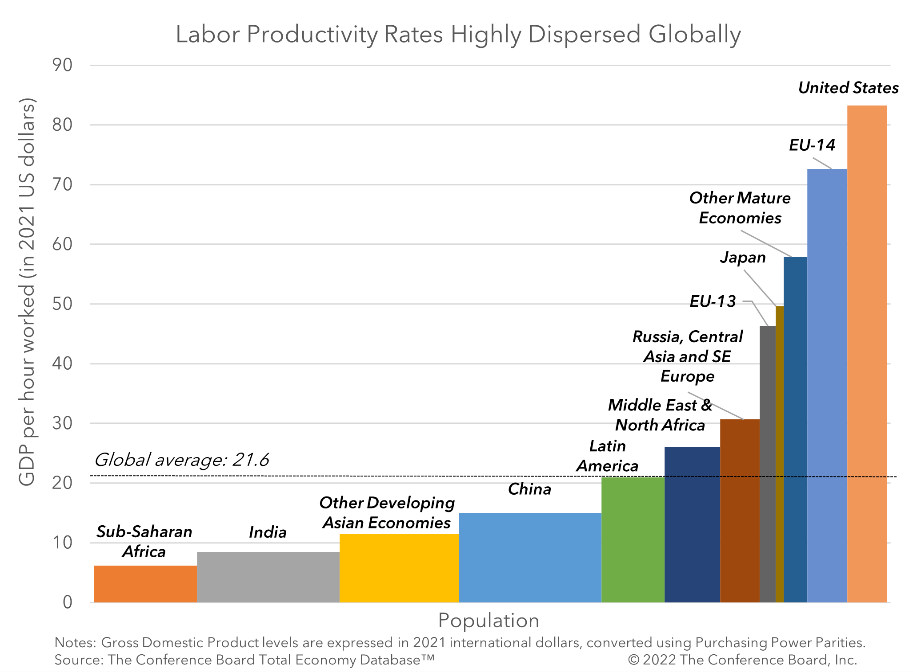

In 1990, the U.S. accounted for a quarter of total global output, essentially the same percentage today, even in the rising power and influence of China and India. We represent nearly 60% of the collective GDP of the G7, the most of all other developed nations. Our economic productivity is much higher than that of Europe or Japan. American companies own more than 20% of patents registered abroad, more than China and Germany combined.

Regardless, and as I stated in unequivocal terms last quarter, we are more than cognizant of the challenges that lie ahead and are acting accordingly in all aspects of the business. As I mentioned earlier, our portfolio is mostly tracking to budget and plan, at least on operations. Debt service, including reserves for interest rate caps, on our floating-rate debt is a different story, and we continue to pursue options to convert this debt to fixed rate via cash-in refinancings. Ironically, while higher interest rates cause debt service pain, we benefit from higher rates inasmuch as the cost of renting becomes far more favorable vis a vis buying.

Meanwhile, we do not intend on ignoring potentially attractive acquisition opportunities when they present themselves, though they are certainly not easy to find (bid-ask spreads between potential buyers and sellers remain wide), and transaction volume has declined substantially, consistent with the loan data I provided earlier. According to CoStar, multifamily sales volume fell 74% in the first quarter of the year, the largest year-over-year drop since the first quarter of 2009, at or near the trough during the Great Financial Crisis. We were pleased to acquire the attractive three asset, Inland Empire based portfolio here in Southern California in an off-market transaction and are still soliciting investor capital for that particular transaction, so I hope you might take a look at that opportunity.

Finally, thank you for supporting the firm and its endeavors, even in these challenging times. Rest assured we take our role as a fiduciary seriously and will continue to do our best navigating these tricky times and markets, providing our views, perspectives, and relevant market and property-specific information in a timely and transparent fashion, which I hope is part our corporate DNA. Please feel free to reach out to me or a member of our investor relations team (Aimee DeFord and Tania Mirchandani) should you have any questions, concerns, or other needs regarding either your existing investments or opportunities we are pursuing.

Best,

Eric Sussman

Managing Partner

“There is nothing more deceptive than an obvious fact.”

-Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

“Value-add multifamily real estate is a canvas of potential waiting to be transformed into a masterpiece of profit and social impact.”

–Fictional quote created by ChatGPT

“Uncertainty is the only certainty there is, and knowing how to live with insecurity is the only security.”

-John Allen Paulos

I have often said that the only constant in life and markets is change and my, oh my, did the first quarter of 2023 live up to that adage, trite as it might be. In what seemed to be the blink of an eye, we had the beginning and apparent passing of a banking crisis, the introduction and seemingly widespread use of ChatGPT, an eerily effective artificial intelligence tool, and the historic indictment of a former president. To put it in college basketball terms, we experienced several March Madness moments during the most recent quarter. These whiplash-like news events echo that famous quote from one of the characters in Ernest Hemingway’s, “The Sun Also Rises,” who responds when asked about his financial woes and how he went bankrupt: “Two ways. Gradually, and then suddenly.”

Since there are lots of newsworthy tidbits to cover, perhaps I should just get on with it and summarize the highlights, or lowlights, from the quarter.

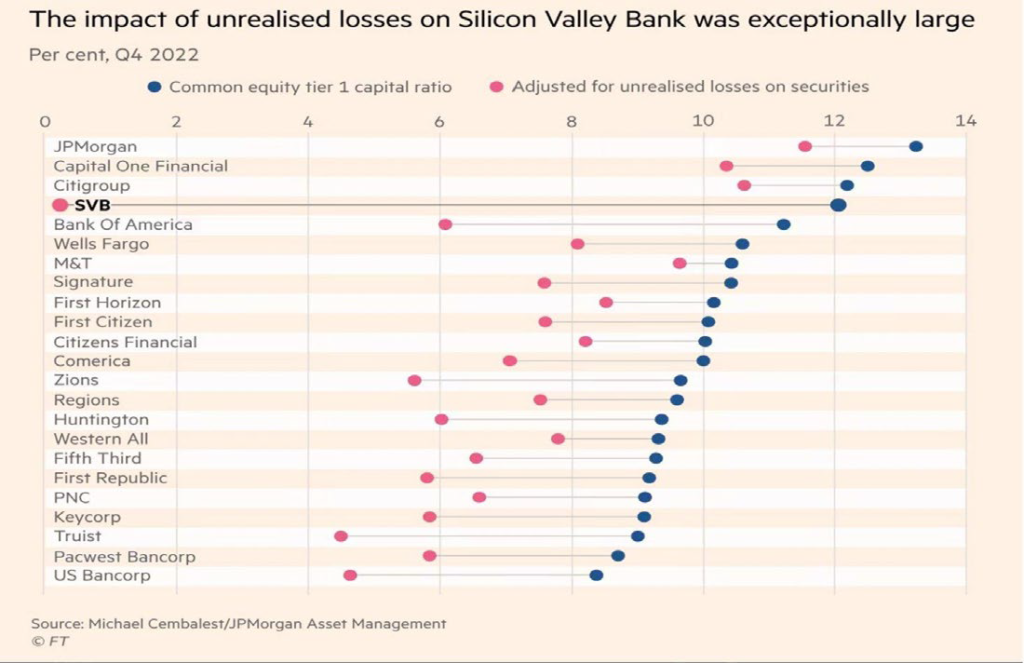

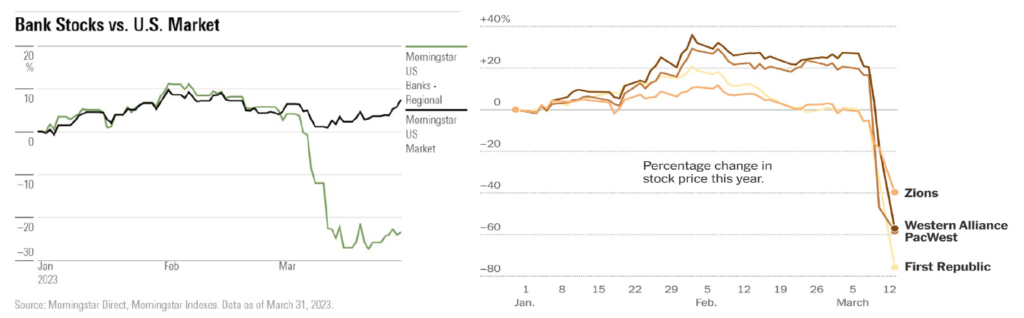

• In a matter of days in mid-March, Silicon Valley Bank went down the proverbial tubes following a bank run (or perhaps more aptly described as a “mouse click stampede”), representing the second largest bank failure in U.S. history and the largest since the Great Financial Crisis. Two days later, Signature Bank, not wanting to miss out on the fun, was also forced to close its doors. A combination of poor risk management (mismatching of asset and liability duration, excessive investment in shorter-term Treasuries and/or long-term fixed rate loans) and related unrealized losses, technological change, anachronistic FDIC insurance and financial accounting rules, and underlying bank fundamentals (e.g., high leverage, thin margins, asset illiquidity) not only sealed their fates, but revealed fundamental risks across the entire banking industry, especially among smaller, less diversified regional and community banks (e.g., First Republic, Zion’s, Pacific West).

2 | P a g e

Not surprisingly, bank stocks were crushed during the quarter, with the KBW Nasdaq Bank Stock Index down nearly 35% year-to-date. The impact of these recent events will reverberate during the remainder of 2023 and 2024 through decreased bank profitability (if not additional failures), reduced lending activity, and increasing withdrawals of deposits, all increasing the risk of recession and overall systemic risk.

Across the pond, Credit Suisse, the global investment bank and financial services firm, was purchased by UBS in a bailout transaction brokered by the Swiss government. Bank runs and related contagion are indeed a thing. Fortunately, quick Fed intervention and the collective efforts of other banks to prop up competitors apparently saved the day here at home, at least for the time being.

Specifically, a group of 11 financial institutions, including B of A, Well Fargo, Citigroup, and JP Morgan agreed to deposit a total $30 billion in First Republic to demonstrate confidence in the banking system and First Republic, specifically. I cannot recall ever witnessing anything comparable. Sure, Warren Buffett and Berkshire Hathaway lent $10 billion to Goldman Sachs and General Electric during the Great Financial Crisis, but that was quite a different story. In any event, bank stocks seemed to substantially stabilize during the last half of March. Given the recent positive earnings announcements from JP Morgan and Citibank, it may end up being a “tale of two types of banks” or the financial equivalent of Beauty and the Beast, where large, diversified, money center banks end up benefitting from the market turbulence at the expense of smaller community and regional institutions.

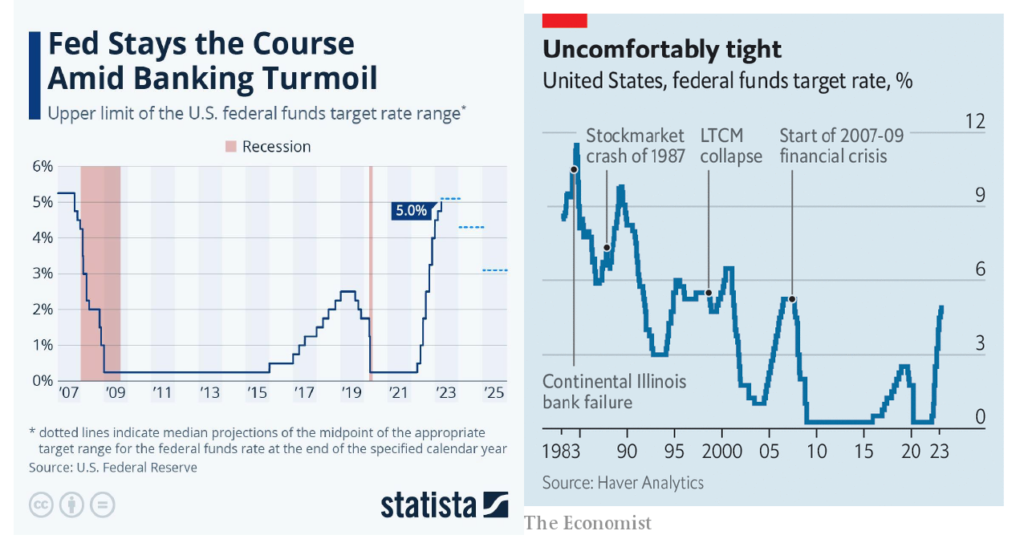

• The Federal Reserve, in the wake of the crisis, short-lived as it might have been, was compelled to rethink its sledgehammer interest-rate strategy and better balance potentially competing objectives of reining in inflation while minimizing strain on and risk of failure of member banks. The Fed agreed to backstop all deposits at both Silicon Valley and Signature Bank and “only” increased the Federal Funds Rate by 0.25% last month, instead of the 0.50% increase that had previously been anticipated. While the Fed has indicated that one more rate increase is likely this year, no one should be counting them chickens before they hatch. As I have said many times, Fed Chair Powell is trying to thread one very challenging needle.

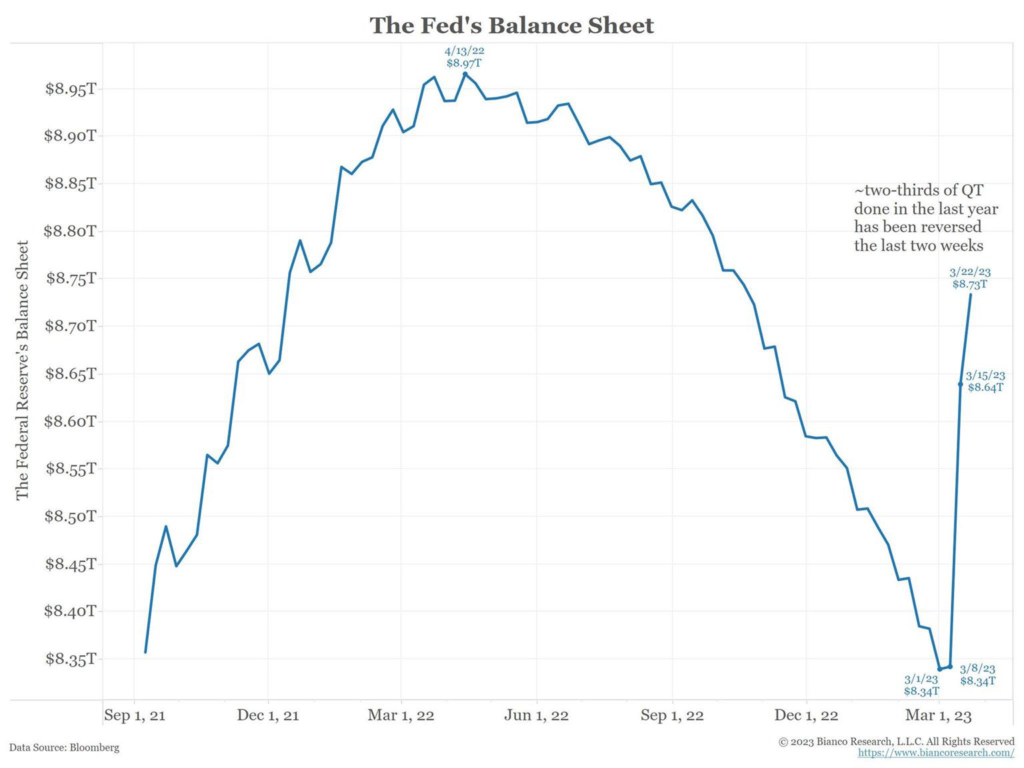

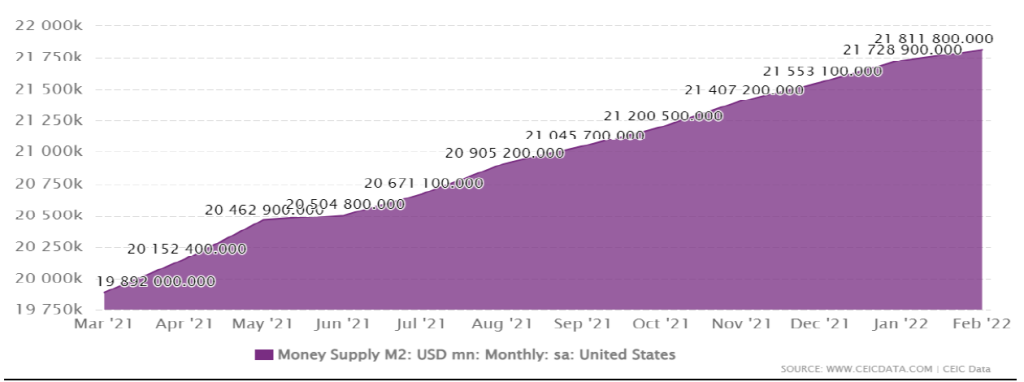

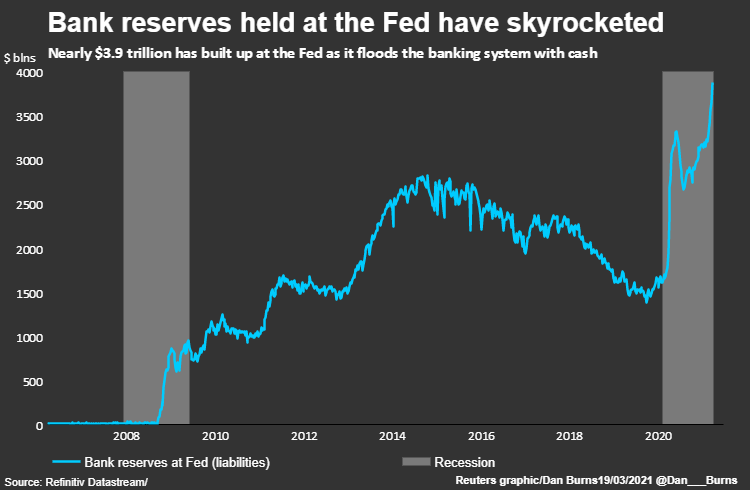

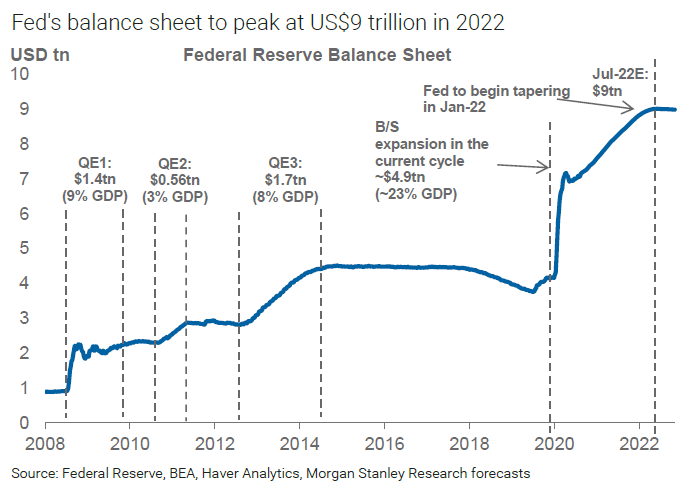

Meanwhile, this aggressive, if not wholly responsible and reasonable Fed response, comes at a cost, of course. The Federal Reserve’s largesse and unprecedented money-printing and quantitative easing endeavors in recent years, which bloated its balance sheet from some $5 trillion (yes, trillion, with a “t”) before the pandemic began, to nearly $9 trillion last April, has been materially responsible for the inflationary pressures we have experienced over the past 18 months or so. Through subsequent monetary tightening efforts, the Fed had successfully shrunk its balance sheet to $8.3 trillion by the beginning of March. And then came the banking shenanigans, the Fed’s response, and in a mere two weeks, some two-thirds of the Fed’s tightening endeavors had been undone. The best laid plans of mice and the Fed, I suppose.

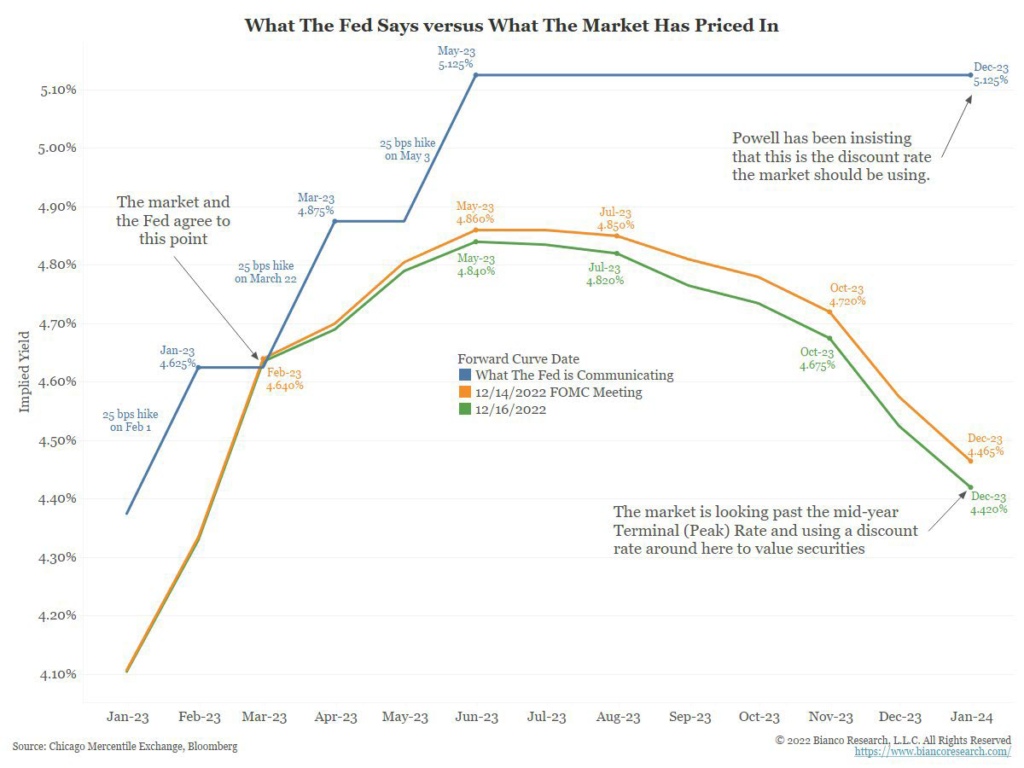

So, where does the Fed go from here? It is hard to say, of course, but there seems to be a disconnect between what the Fed is telegraphing as opposed to what the market is anticipating.

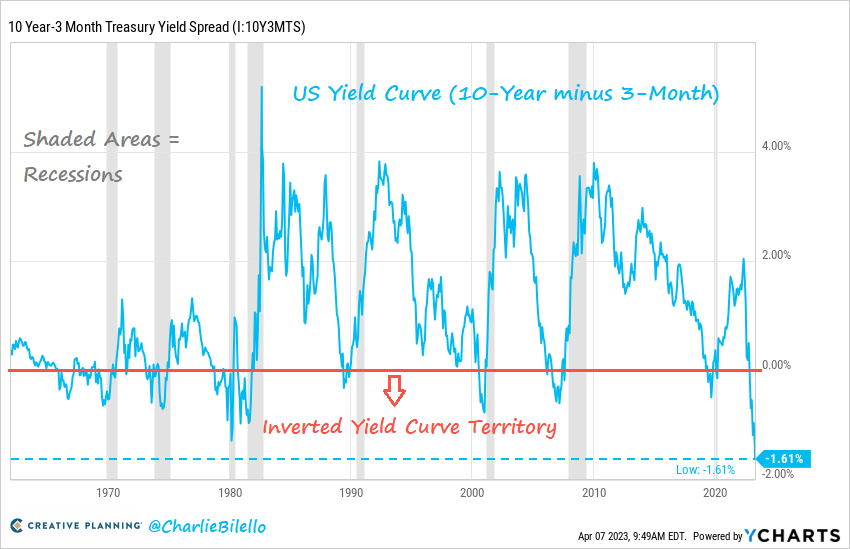

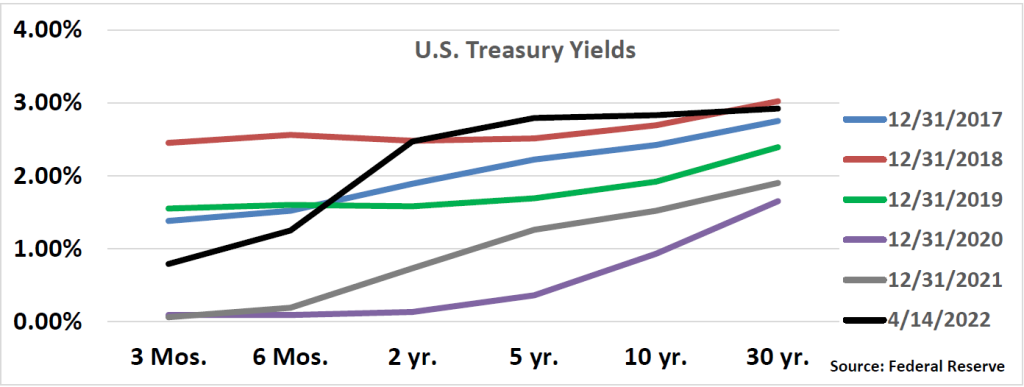

After all, the spread between short- (three-month) and long-term (10-year) Treasuries has never been wider, resulting in the most inverted yield curve in history.

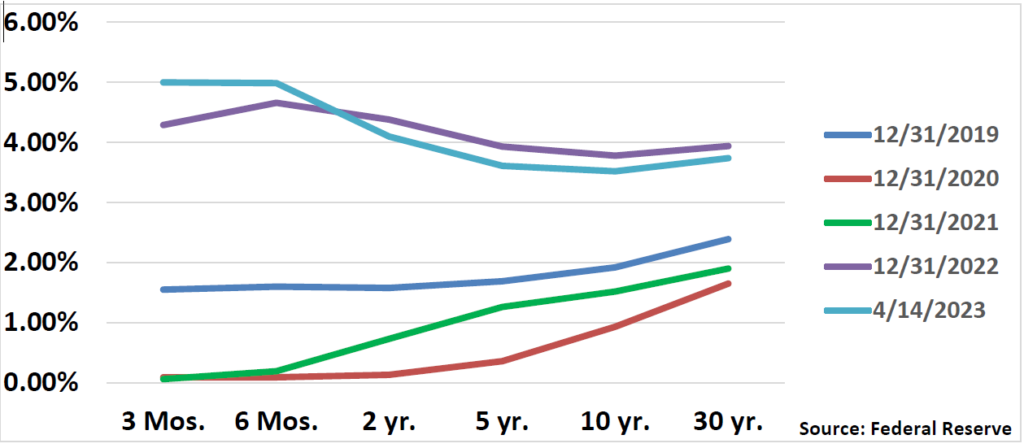

Seen another way, longer-term Treasury rates on two- and ten-year maturities have not changed all that much since the beginning of the year and are actually modestly lower, but rates on the shorter end of the curve have risen. Such a steep inversion would almost certainly foretell a significant economic slowdown, if not recession, but the equity and labor markets (see below) do not seem convinced.

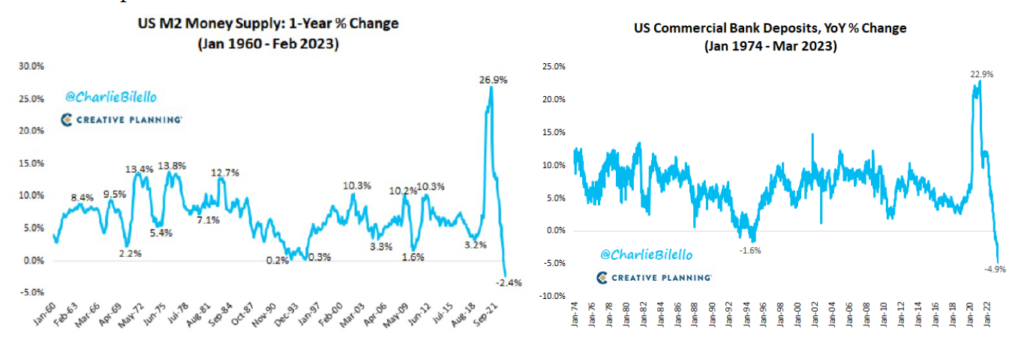

• M2 money supply, in turn, witnessed its largest decline in history during the quarter, as depositors pulled funds from banks in record numbers, preferring risk-free (read: principal-protected) Treasuries and non-bank money market funds versus potentially at-risk bank deposits. It is my strong view that the Fed needs to revisit the anachronistic FDIC-insured limits, which were last changed following the Great Financial Crisis. There is no way that depositors can adequately assess the financial risk of banks in which their deposits are held. That would be asking too much of even this CPA and accounting professor, let alone other depositors, and arguments about moral hazards do not seem very compelling to me, at least when it comes to depositors. Employees, management, Board members, and capital providers (debt holders and stock owners) should individually and collectively bear the risks of bank failures, in my view, not depositors.

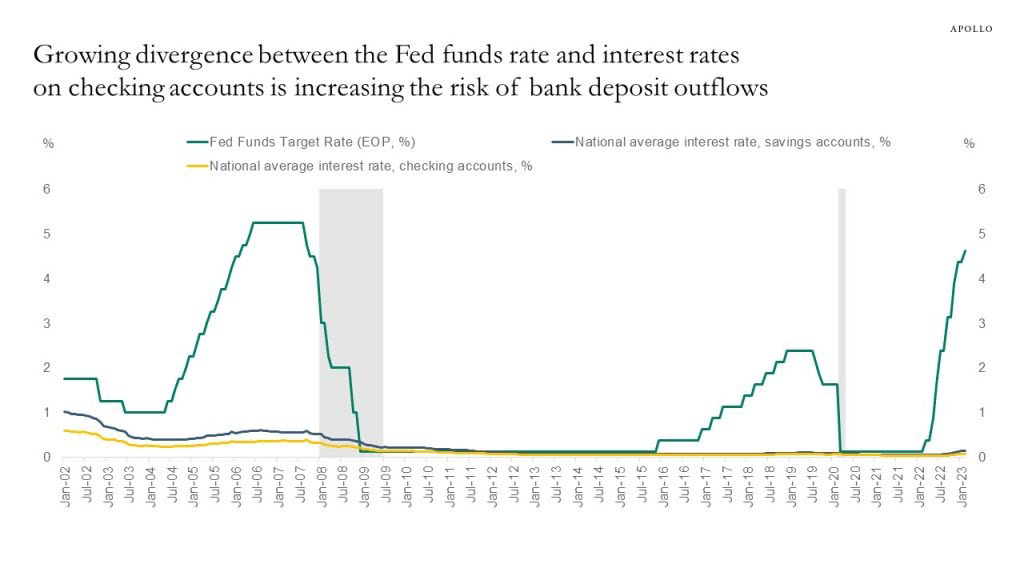

In any case, let’s be clear. The entire banking system remains at risk and subject to whimsical shifts in depositor confidence and psychology, especially given the wide spread between yields on short-term debt securities (think two-year Treasuries) and the Fed Funds rate, both of which approximate 5.0%, and rates banks are willing to pay on many demand deposits, something between jack and squat, keeping in mind that significant balances of these demand deposits are likely uninsured under current rules.

Finally, record levels of commercial mortgages come due this year and next, about $500 billion each year, much of which is held by those smaller regional and community banks, those with less than $250 billion in assets. It remains to be seen how many of those loans are repaid, extended, or ultimately defaulted on, given the significantly higher cost of capital, declines in commercial real estate values, and weakening fundamentals. Maturing commercial real estate loans will provide a worthy adversary to bank balance sheets, especially in the event of increasing delinquencies and/or defaults.

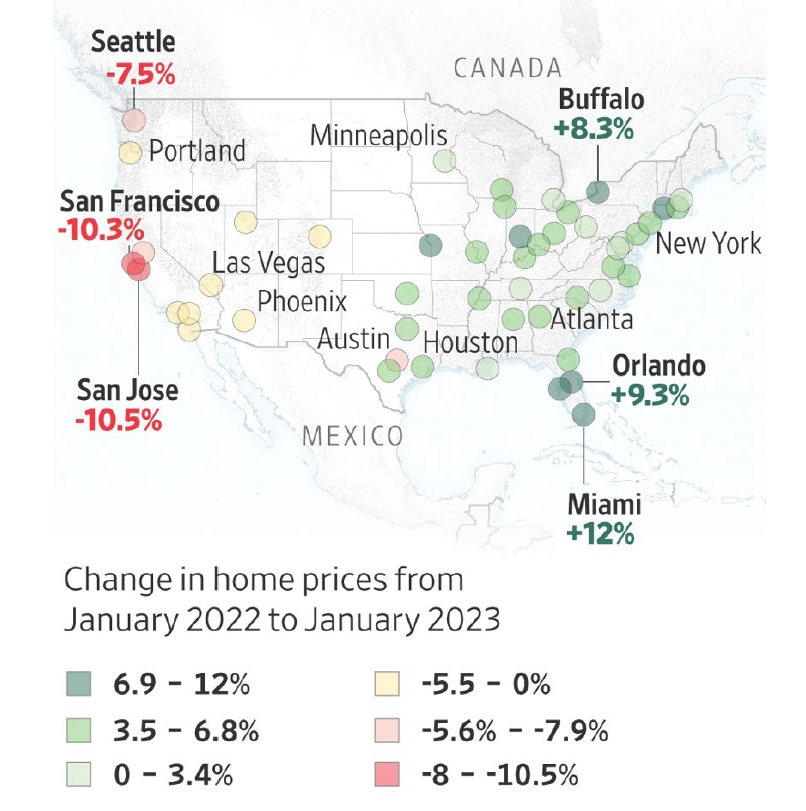

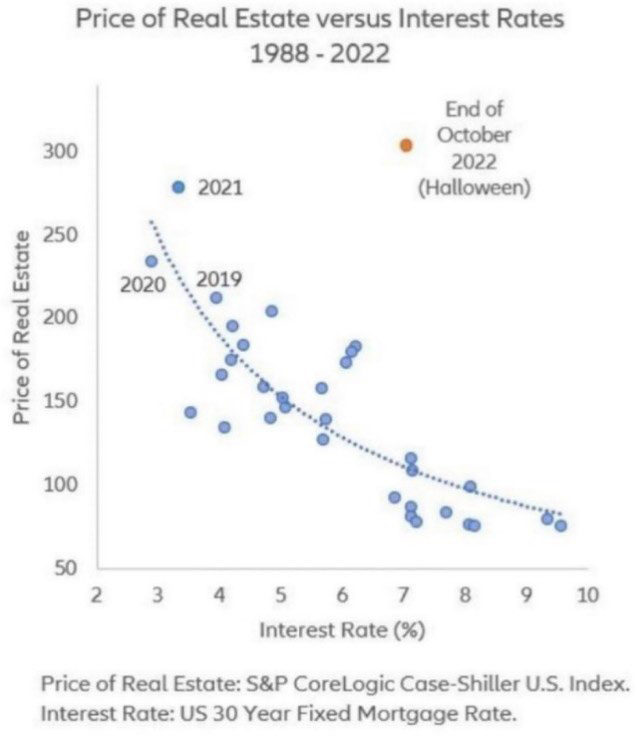

• Housing prices remain firm, though one can argue that it is a tale of different housing markets and different time periods. In all 12 of the major housing markets west of Texas (Austin), home prices declined in January, year-over-year. However, prices actually rose in all markets to the east. Perhaps, it is partly a question of what goes up, must come down (or at least revert to the mean), but the disparity more likely reflects the relative difference in job markets within these geographic locations. Specifically, most of the job losses announced since last year have been in the tech sector, so markets with disproportionate exposure to these industries (e.g., San Francisco, Seattle, Los Angeles) have been hardest hit.

However, just as in so much other economic data, year-over-year figures often mask nearer-term trends. Since last summer, home prices across the country have dropped for seven straight months (through January). From June’s peak, national housing prices have declined about 5.3%, but are down much more in San Francisco and Seattle, 14.8% and 17.2%, respectively.

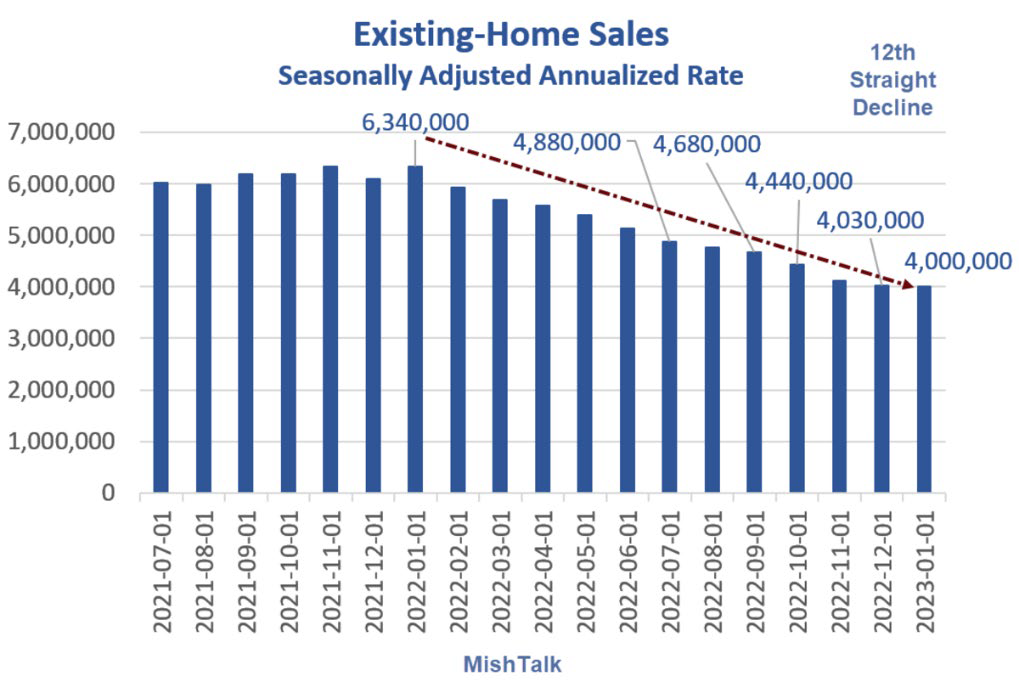

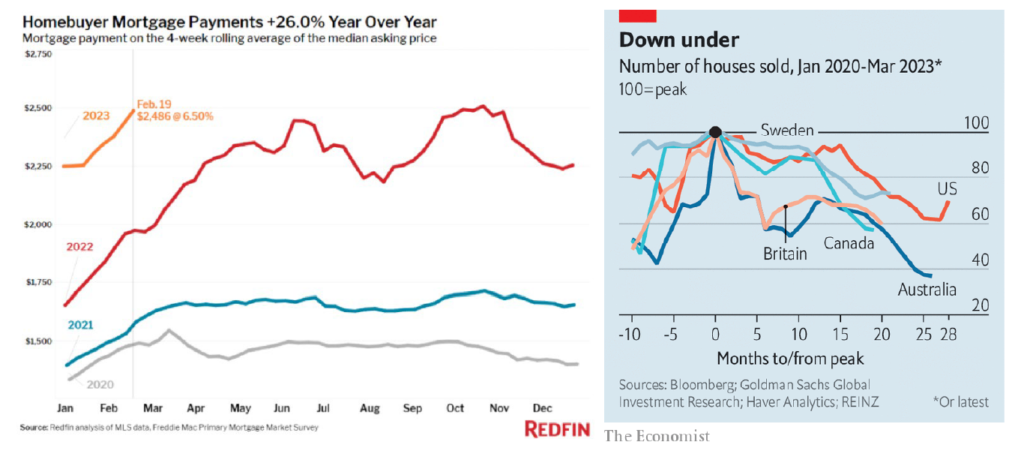

Moreover, all housing pricing data may be a tad skewed because of the sharp drop in transaction volume. Through February, overall home sales are down 22.6% year-over-year, 14.5% from January, and have declined for 12 straight months, whether considering overall or seasonally adjusted data. Higher mortgage rates and declines in consumer (read: homebuyer) confidence are to blame. At last glance, 30-year fixed rate mortgages nationally averaged 6.27%, according to Freddie Mac. While well off the 7.08% rate hit last year, rates are obviously more than double those witnessed in 2021.

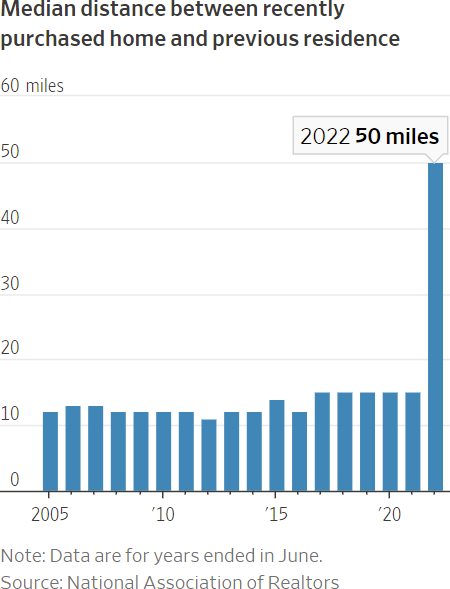

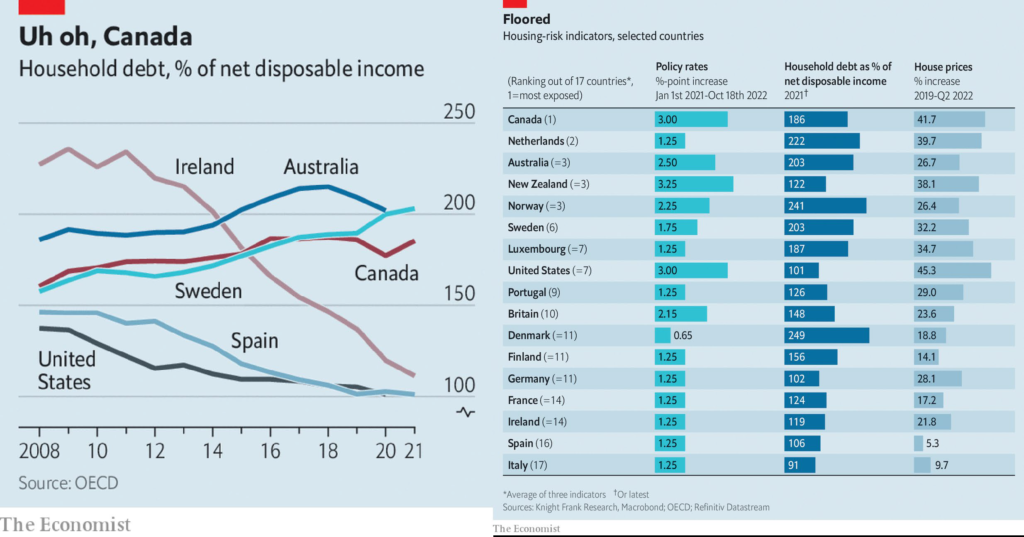

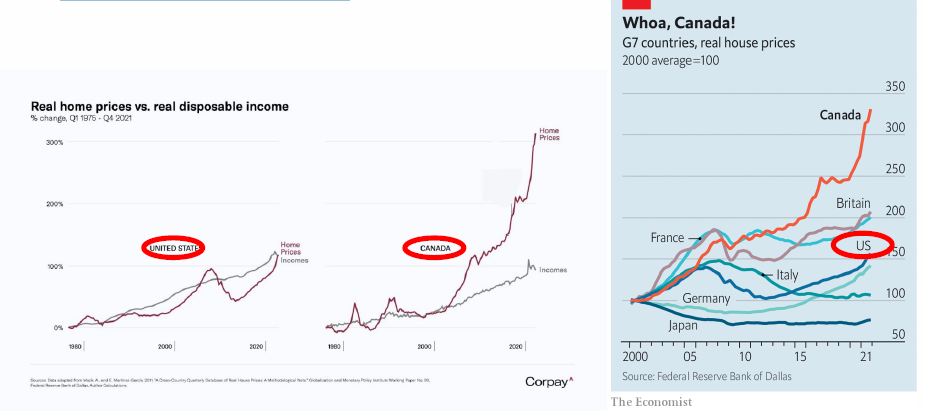

In the U.S., the widespread use of long-term, fixed rate mortgages provides a certain buffer to downside risk, as borrowers are able to better able to meet mortgage obligations and are not forced to sell their homes as a result of short-term financial or economic distress. In fact, anyone who acquired or refinanced a home in 2020 or 2021 is now the fortunate owner of “mortgage handcuffs,” (insert joke here), likely unable or reluctant to sell and/or relocate because any subsequent home they might purchase would require substantially mortgage payments (over 25%). The widespread use of fixed-rate mortgages also explains why housing markets in Sweden, Canada, and Australia, where floating-rate mortgages on single-family homes are far more common, have been hit much harder than here in the U.S.

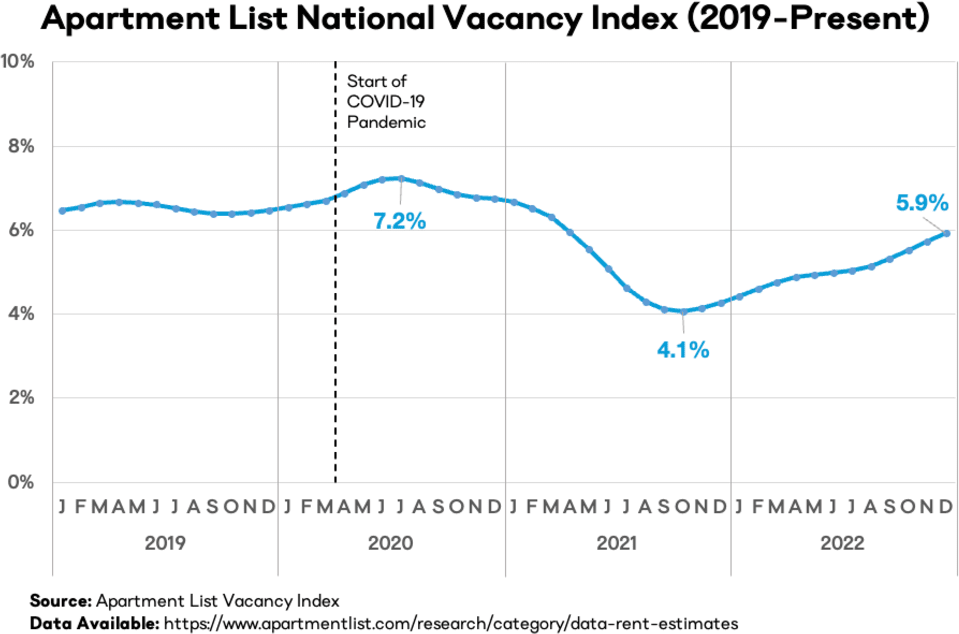

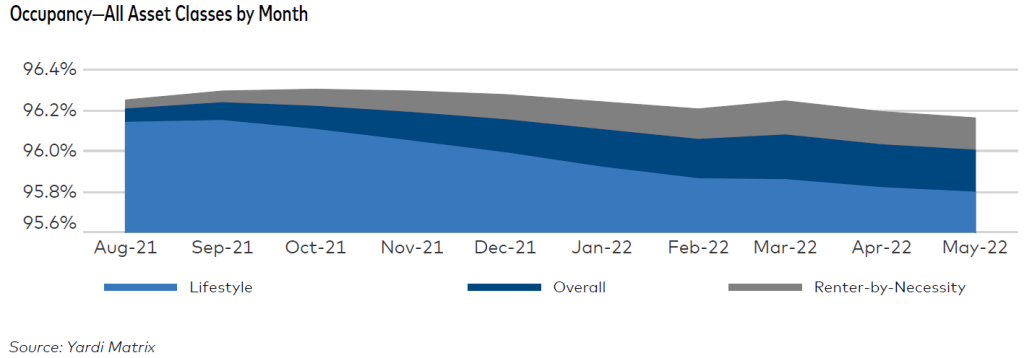

• Meanwhile, data surrounding multifamily markets is decidedly mixed. According to Redfin, asking rents for apartment units fell in every metropolitan area in the U.S. over the last eight months, reflecting not only normal seasonal slowdowns (August through February are traditionally slow leasing periods), but broader indigestion as several markets which saw significant construction activity must “absorb” new units coming to market. Developers of these new projects are engaged in aggressive lease-up efforts, offering generous move-in specials and rent concessions.

According to Redfin, median rent nationally fell 0.4% in March, year-over-year, the first annual decline since March 2020, the start of the pandemic. Rents nationally are down 3.5% since August, with the largest declines in Austin (11%) and Chicago (more than 9%). Other cities with rent declines of 3% or less include Phoenix, Las Vegas, New Orleans, Houston, and Atlanta. However, rents still remain far higher than before the pandemic, up 20 to 35% in many, if not most, markets. And perhaps more importantly, rents in March appear to have rebounded, at least compared to February, up 0.5%, according to Apartment List. Again, year-over-year data can really mask more recent, and arguably, more probative data points.

However, while directionally consistent with Redfin, Apartment List’s provides slightly different data regarding specific markets, rental growth (or declines) in said markets, over differing time periods. Anecdotally, those markets with greater exposure to technology and other white-collar jobs (e.g., San Francisco, San Jose, New York, Boston, Los Angeles) and those that experienced the greatest rental growth since the pandemic began (e.g., Austin, Atlanta, Phoenix) are generally those that are experiencing the most modest rental growth, or even experiencing rental declines, at least in recent months.

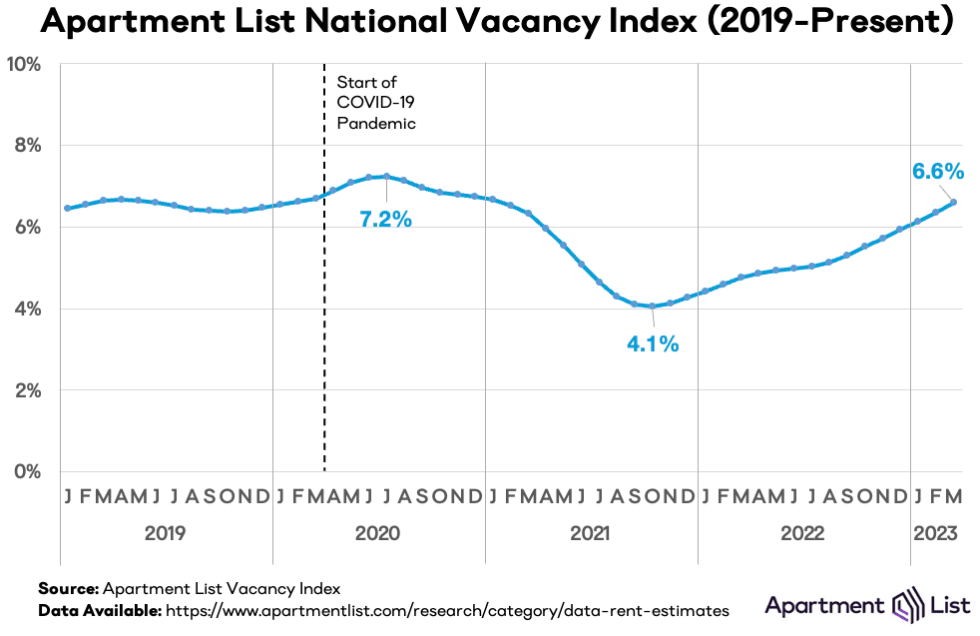

Meanwhile, national vacancy rates ticked up to 6.6%, their highest level since the summer of 2020, again reflecting uninspiring economic growth, higher inflation, and new supply.

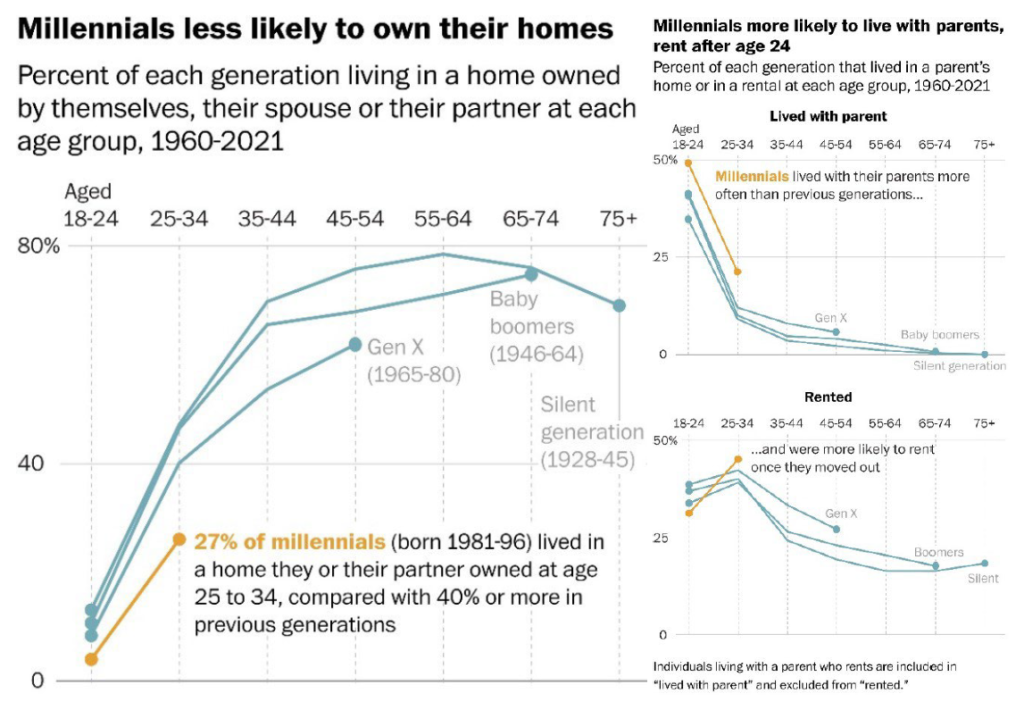

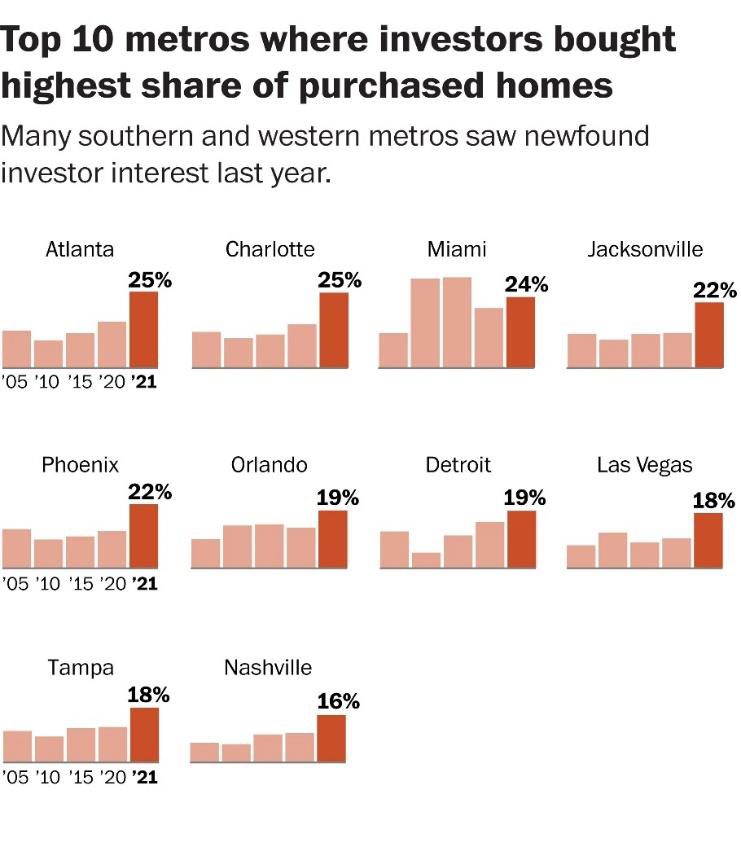

Regardless of shorter-term trends or blips, the “affordability gap,” the difference between mortgage costs and effective apartment rents has never been wider, and homeownership remains decidedly out of reach for most, even two-income, white collar- households. But rising interest rates, higher home prices and decreasing inventory aren’t the only things making it difficult to buy a home these days. Last year, nearly a third of U.S. homes were purchased with cash, according to Redfin, likely foreign and/or institutional buyers. That’s an eight percent increase from 2021, continuing a trend that started during the pandemic, and representing levels not seen since 2014, when the housing market was on the rebound following the Great Financial Crisis. The rise of all-cash purchases comes at a time when the average home buyer is increasingly likely to be white, wealthy, and older, with the proportion of first-time buyers at its lowest in more than 40 years.

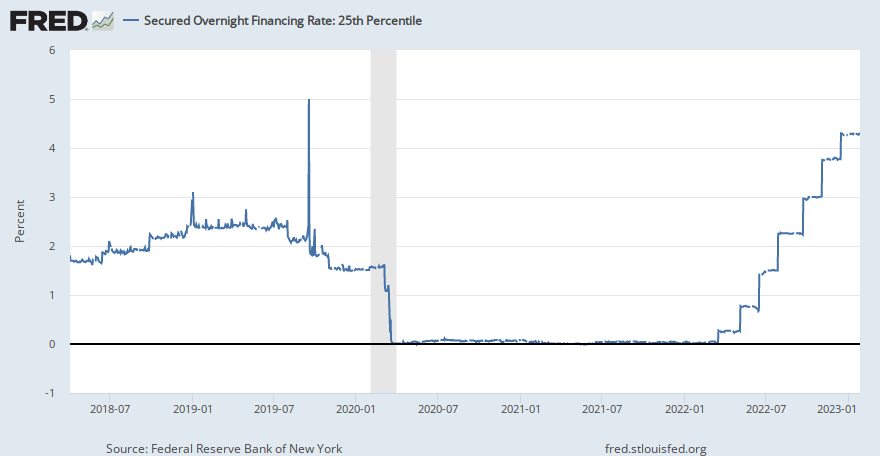

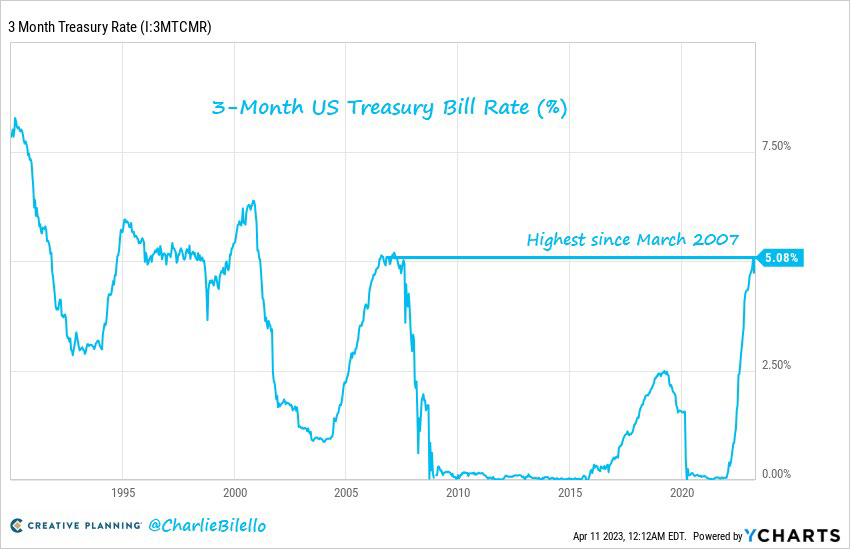

However, higher capital costs and uncertainty surrounding the economy and supply will continue to weigh on apartment valuations and transaction volumes. All property owners, especially those with floating-rate mortgages, are grappling with surges in short-term rates and the increasing costs associated with hedging exposure to such rates (interest rate caps), as yields on both SOFR (Secured Overnight Financing Rate) and 3-month Treasuries have spiked to their highest levels on record, or at least since the period preceding the Great Financial Crisis.

The three-month Treasury Bill yield rose to 5.08% this month (5.06% at last glance), its highest level since March 2007. Keep in mind that the yield on short-term Treasuries was 0.70% a year ago, and a measly 0.02% two years ago. Ouch.

Thus, it is no surprise that some apartment owners are struggling. In early April, a large apartment project in Houston, consisting of 3,200 units, was taken back by its lender in early April. Veritas, a San Francisco based PW firm defaulted on a $450 million loan backed by rent-controlled apartments, and Blackstone is currently negotiating with its lenders on portfolio of apartment buildings in NYC.

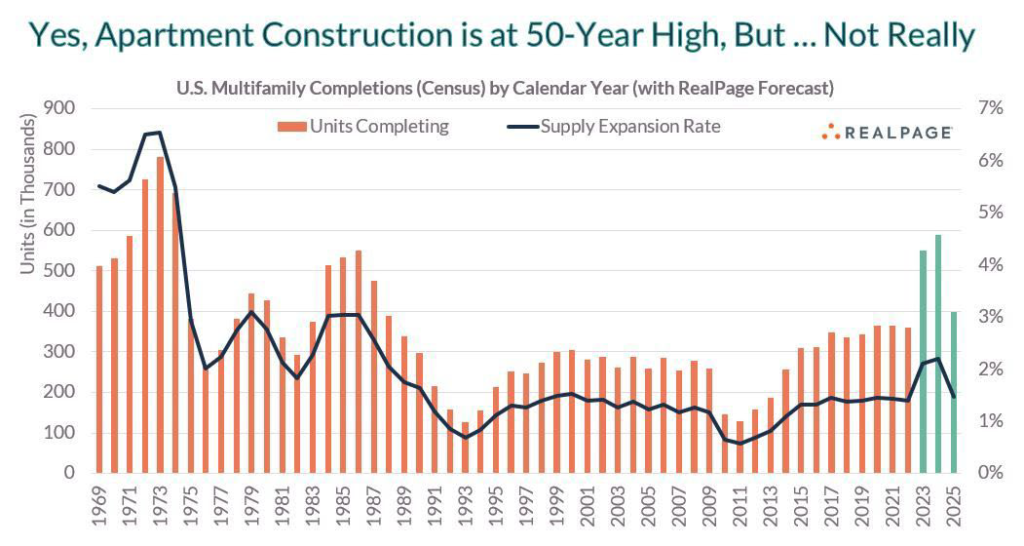

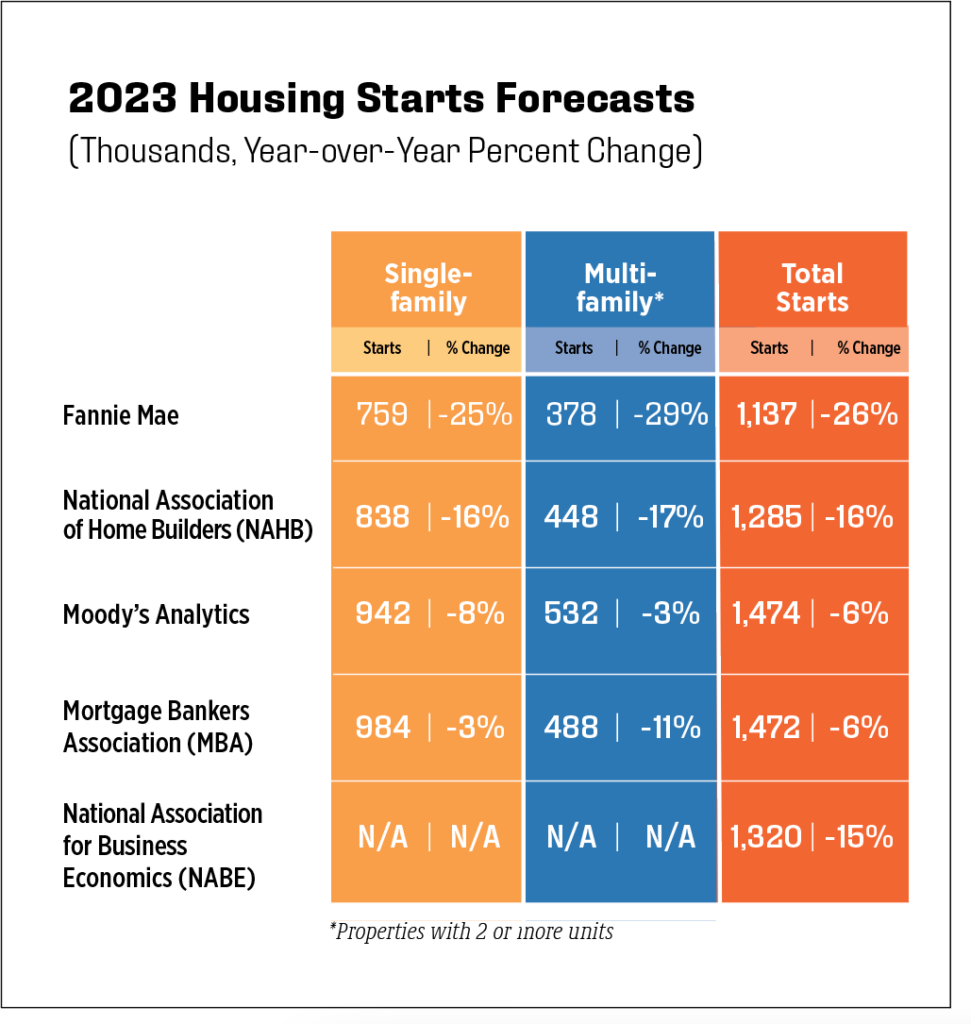

Meanwhile, the multifamily market continues to grapple with increasing supply in several markets. However, while there are about one million multifamily units under construction nationally, one should be cynical when reading headlines claiming that multifamily construction is at its highest level in 50 years, as proclaimed in a recent article published by MHN, Multi-Housing News, since such a claim is inherently misleading or at least incomplete.

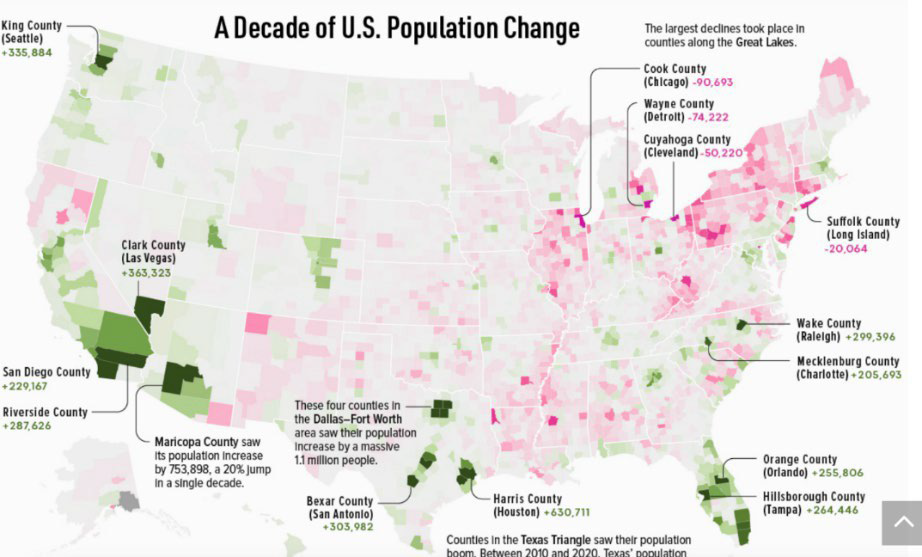

For one thing, there are far more multifamily units in the U.S. today than in 1970, so on a relative basis, the increase in absolute construction activity is about a third of what it was in the early 1970’s. Those construction starts in the 1970’s tended to be smaller projects, 20 units or fewer, which were approved and built far more quickly than today. For those of you from Southern California, think about the apartment buildings you routinely see in submarkets like Hollywood, Brentwood, and/or Koreatown. The larger projects which dominate construction starts today take longer to build and bring to market. Finally, the U.S. population has grown significantly since the early 1970’s. For example, there are nearly double the number of adults aged between 25 and 54 today, and those prospective renters or homebuyers reside in different markets than they did back then, reflecting population and demographic shifts, away from both coasts and into markets in the Southwest and Sunbelt, for example.

Now, don’t misunderstand me, as there are a lot of apartments under construction, which along with those higher capital costs and operating expenses (e.g., insurance, labor), are impacting fundamentals and will continue to do so through at least the end of this year, especially in certain markets. However, demand will eventually catch up with supply and with the cost of single-family homes being essentially out of reach for so many, apartments will benefit at least on a relative basis. While the road will be challenging for both developers of new product and operators and owners of existing stock, I believe that the market will stabilize by the end of the first quarter of 2024.

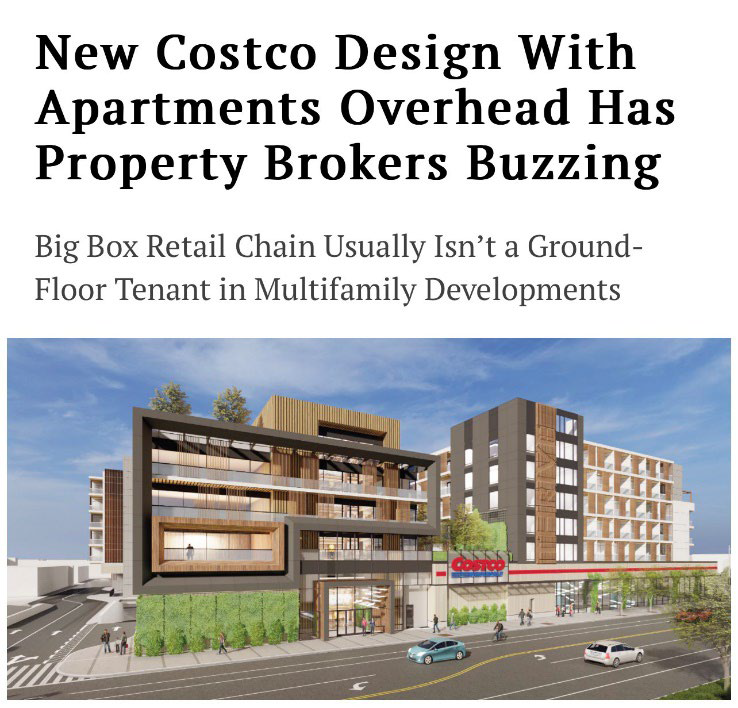

Finally, in what has to be the single most exciting headline in the multifamily space was the news that a local Southern California developer is planning a mixed-use project with apartment units atop a Costco. Imagine, renting an apartment above Costco. You wouldn’t need an on-site gym. Walking the aisles of Costco and lifting cases of drinks and water bottles would provide all the exercise one might need. You could live off of free food samples. If ever one might find heaven on earth, I believe this particular development, if it comes to fruition, would nearly qualify.

• The commercial real estate market, especially the office sector, saw significant weakness and a large number of foreclosures during the quarter, principally in gateway cities: New York, Los Angeles, Boston, and San Francisco. Few landlords can withstand the double whammy of significant increases in interest rates and weakening fundamentals, which will create additional stresses on operators and lenders in coming quarters. As discussed in greater detail below, to say that the fundamentals in the office sector are not pretty would be a profound understatement. While being a multifamily owner/operator/developer is challenging these days, these challenges pale by comparison to those landlords or operators in the office sector.

This quarter my inbox was flooded with one anecdote or headline after another, each highlighting woes in the office market. Here is just a sample, and trust me, this is (sadly), just a sample:

- “Pac Mutual Building in Downtown LA hits the market at half its previous price”

- “Google Parent Alphabet to spend $500M cutting office space this quarter.”

- “California Government to Trim 132 Office Leases”

- “Distress in Office Market Spreads to High-End Buildings”

- “Blackstone unloads two 13-story buildings in Southern California at a big discount”

- “Brookfield defaults on two Los Angeles office towers”

- “Pimco-Owned Office Landlord Defaults on $1.7 Billion Mortgage”

From Los Angeles to New York to Boston to San Diego to Washington D.C. to nearly everywhere in-between, the office market is in a depression and heavily distressed, experiencing rapidly declining rents, increasing vacancies, and comatose-like transaction volume. Shockingly, there are still a fairly large number of new projects coming to market, nearly 124 million square feet across the country, projects that had already been approved, financed, and begun before the turmoil started, so the beatings will continue for some time.

Billions of square feet of office will probably be obsolete by 2030, reflecting significant overbuilding and a greater shift to hybrid work. Sure, some projects will be repositioned, converted to other uses (e.g., healthcare, medtech, housing), but I remain dubious as to whether obsolete office buildings can be practically converted, and in most cases, I suspect buildings will remain vacant for years, ultimately razed and rebuilt for other uses. Impediments from zoning, architectural/design limitations, lack and cost of available financing for such projects, will simply be too great to overcome.

And retail real estate? It is not faring that much better, though the end of the Covid pandemic is certainly a positive for the sector. During the quarter, I read that Simon Property Group, the largest retail landlord in the country, defaulted on a $295 million loan on a 1.2 million square foot shopping center in Orange County, California, and poor Brookfield, repeating its experience on certain office assets, defaulted on a nearly $80 million shopping center loan in Washington state. There is no question that this will be the most challenging commercial real estate cycle since the 1970’s and I see no proverbial light at the end of the tunnel.

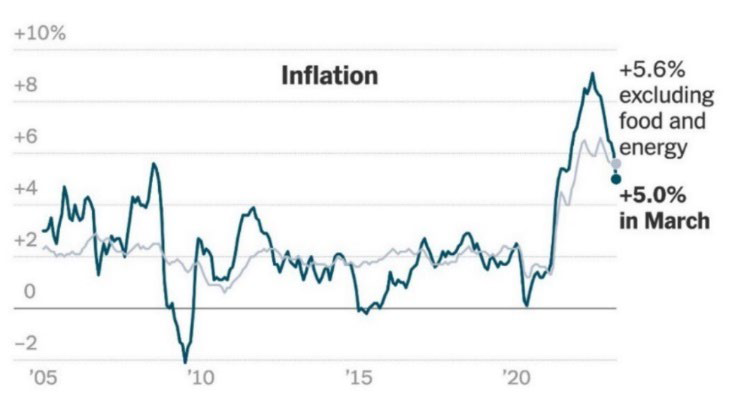

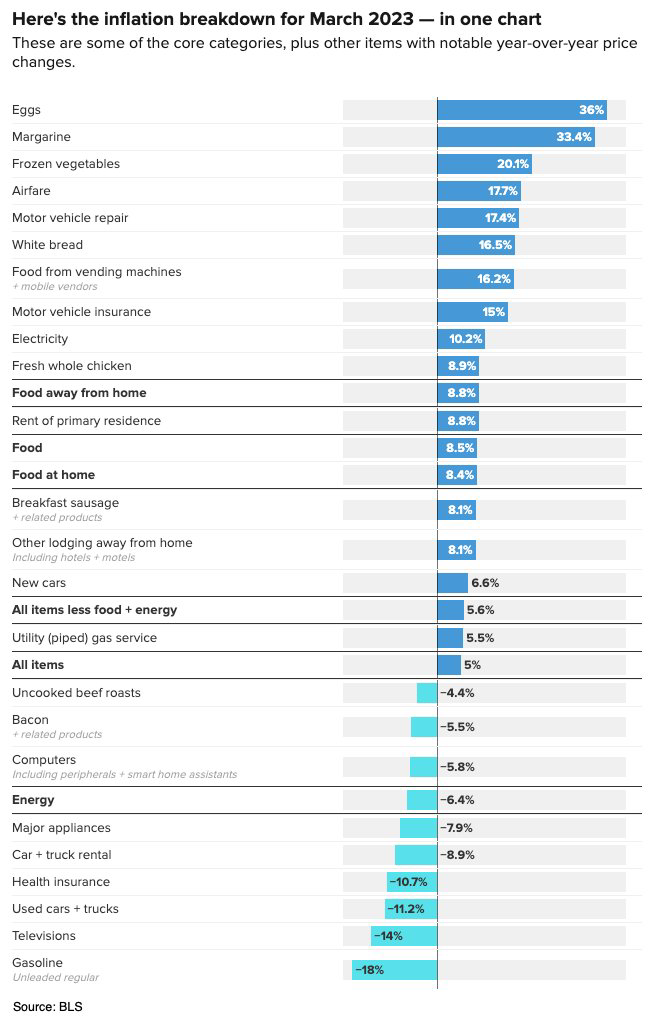

• The Consumer Price Index increased a modest 0.1% in March from the previous month, or 5.0% year-over-year, representing the ninth consecutive decline in year-over-year inflation figures and the lowest inflation levels seen since May 2021. Core inflation (excluding volatile food and energy prices) increased 5.6% year-over-year, driven in large part by continued increases in shelter (housing) costs, which increased 8.2% year-over-year.

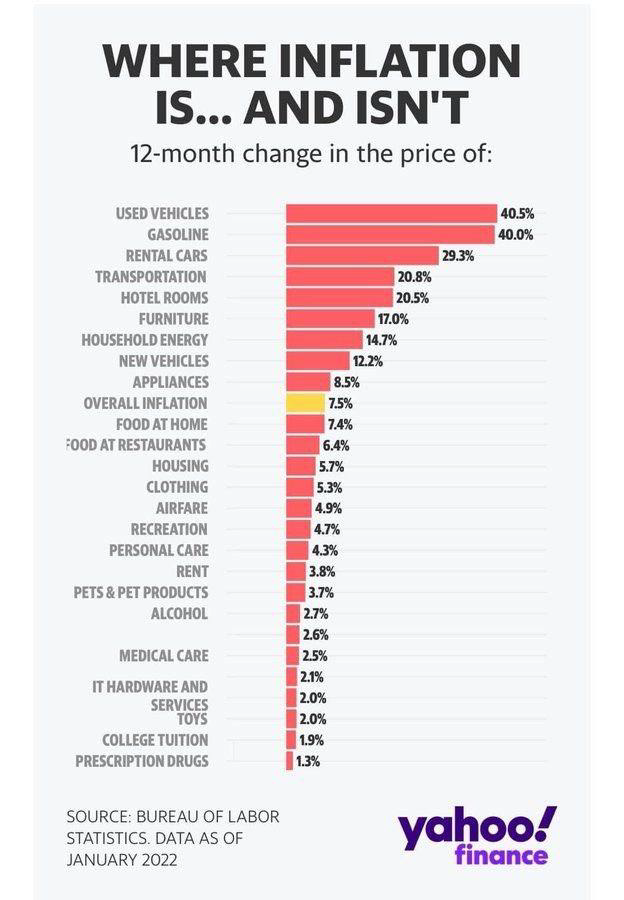

With apologies for the size of this next chart, it provides a more granular and insightful breakdown of the yearly inflation change. However, one should exercise caution in drawing conclusions from year-over-year figures because they can obviously mask shorter-term trends that are perhaps more likely to persist going forward. For example, while egg prices rose an astounding 36% between March 2022 and March 2023, they fell 7% in February and another 11% in March. Thank goodness! One can only eat so much oatmeal, Cheerios, and avocado toast, even in California.

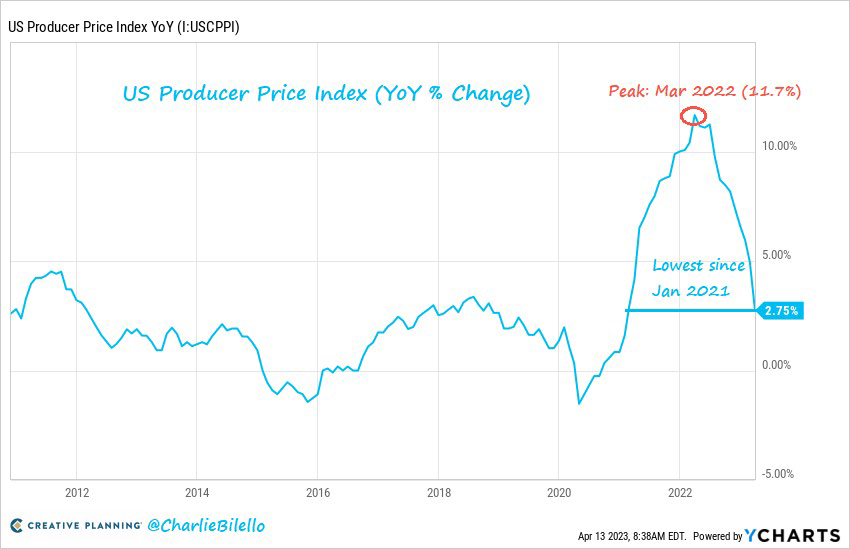

Meanwhile, March 2023 producer prices increased “only” 2.75% over the last year, the smallest increase since January 2021. By comparison, producer prices increased 11.7% in March of 2022 (versus the prior year), so costs have been declining, at least among domestic producers.

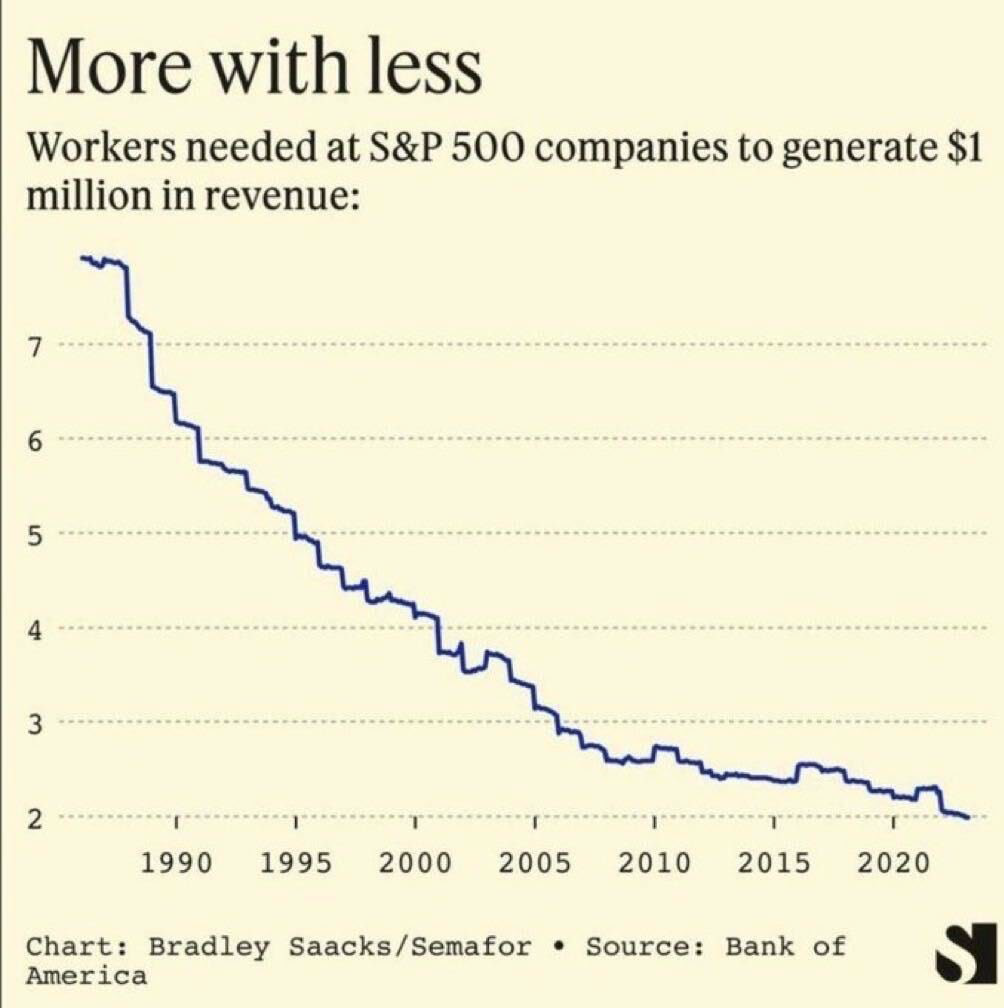

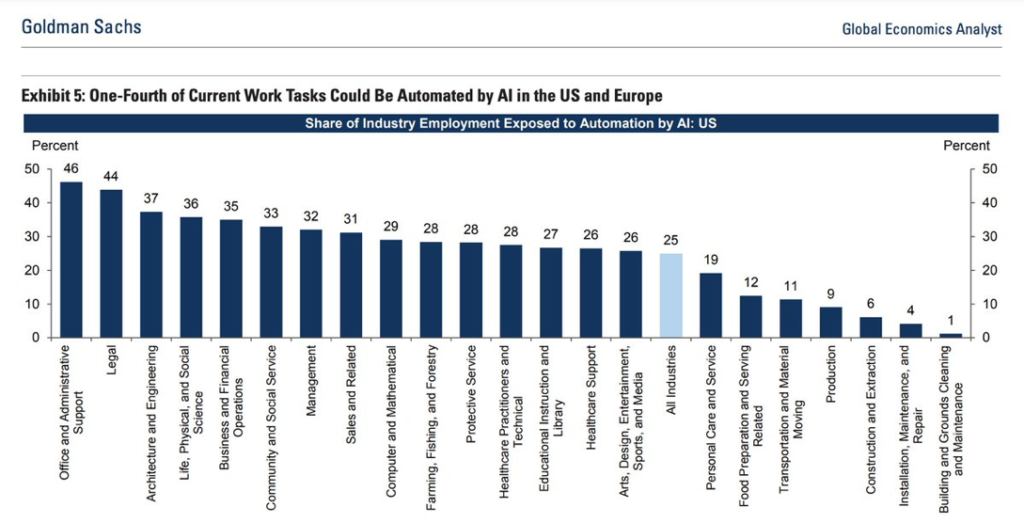

Where inflation goes from here is obviously a big question mark. On the one hand, decreases in housing/shelter costs and in lending activity, coupled with broad demographic and population changes are broadly deflationary. In addition, the continued trend towards automation and yes, AI, should prove deflationary with related changes in labor markets, as evidenced by this interesting graph. Firms require far less workers to generate substantial revenue than in the past.

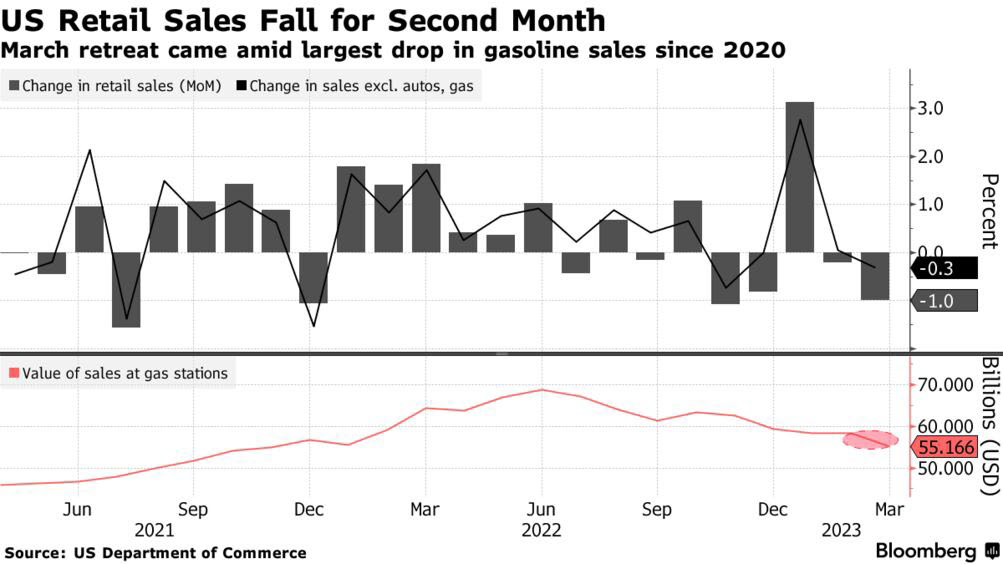

Finally, the consumer seems to be losing some steam, perhaps having finally expended their PPP funds, unemployment benefits, and Covid-related savings when spending dropped like a stone. U.S. retail sales increased only 1.5% in March over the last year, the lowest growth rate since May 2020 and well below the historical average of 4.8%. After adjusting for inflation, the story is worse. Real retail sales fell 3.3% over the last year, the 7th consecutive year-over-year decline.

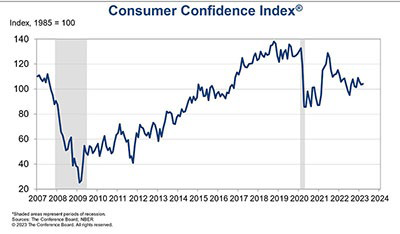

However, data surrounding certain discretionary spending appears contradictory. On the one hand, although I have not been to Las Vegas in recent months in order to obtain data supporting the Sussman Spa Bookings Index (SSBI™), my favorite measure of discretionary spending, I couldn’t help but note that Nevada casinos won nearly $1.24 billion in February, a new record for the month. On the other hand, Darden Restaurants, in a recent earnings call, indicated that households making less than $50K annually were eating less frequently at its Olive Garden and Cheddar’s restaurants according to data, echoing similar comments made by Walmart. Now I realize many reading this memo are not frequent consumers of endless bread sticks at Olive Garden (shame on you), but the anecdotes are consistent with overall trends in retail sales. Recent headlines, especially woes in the banking industry, have understandably weighed on consumer confidence.

In perhaps the scariest data point, “professional economists” (as opposed to the unprofessional or amateur ones) recently surveyed by the Wall Street Journal, project that inflation will slow to 3.1% by end of 2023. My cynicism about such polls is well documented, but if you need any evidence as to how difficult predictions are, not a single one of the economics professionals accurately predicted where interest rates would be at the end of 2022 and not a single number one seed made it to the Final Four in this year’s March Madness. Of course, had my beloved Bruins hoopsters did not sustain the injuries that they experienced and received a number one seed, I am confident we would be hanging up another banner in Westwood. Oh, well. As Andy Dufresne said in the Shawshank Redemption, “Hope is a good thing, maybe the best of things.” I have always liked that quote.

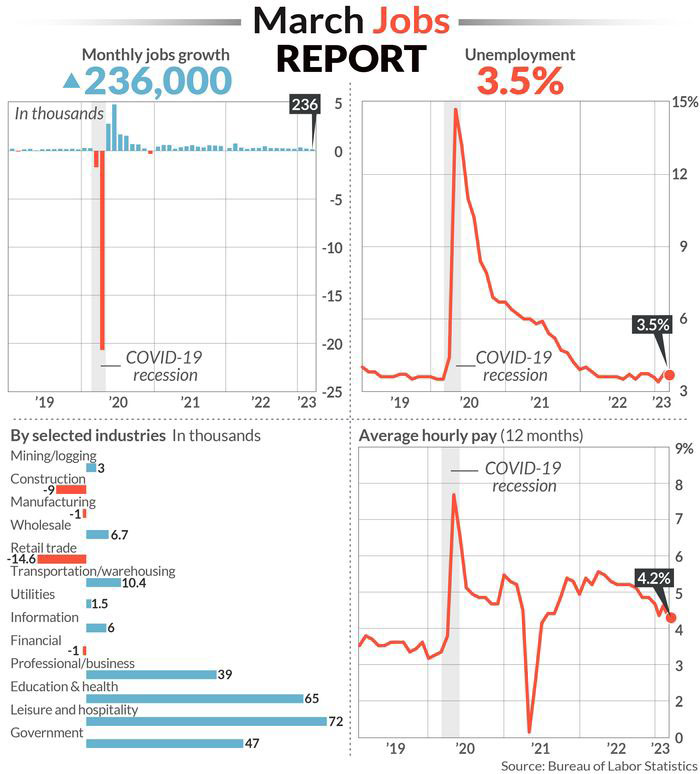

• The job market, while softening, still appears robust, providing a recessionary buffer. The March job report was solid, with an increase of 236,000 new jobs (non-farm) added, slightly exceeding expectations. The unemployment rate fell to 3.5%. Year-over-year average hourly wages increased 4.2%, slightly below the 5.0% inflation rate.

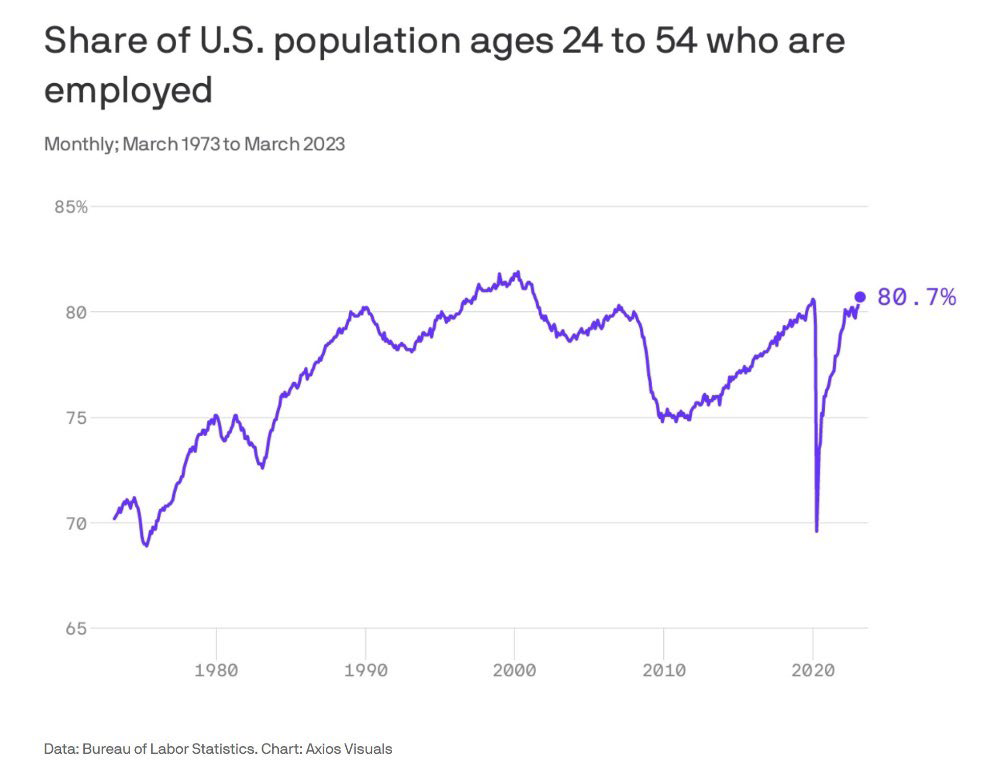

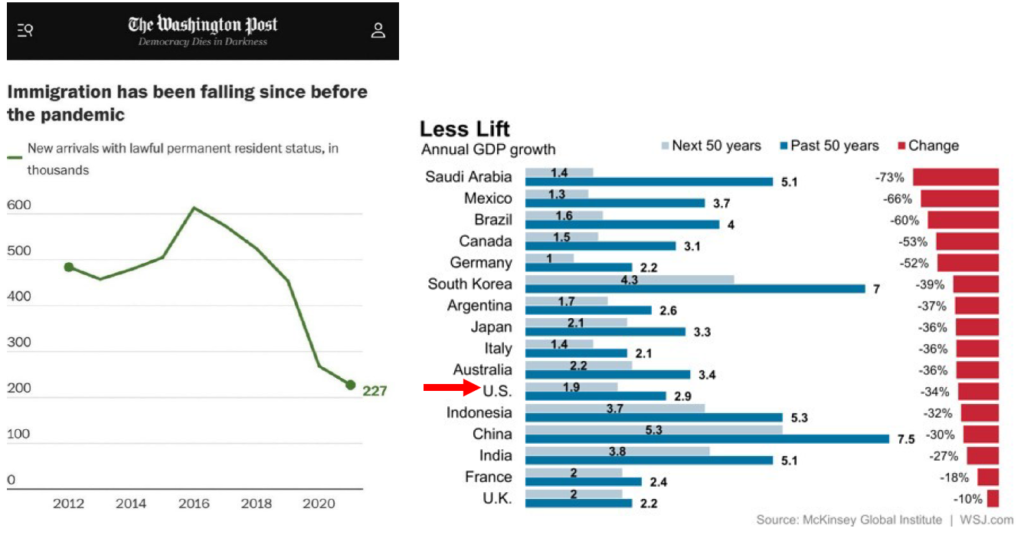

With Baby Boomers (those born after WWII) retiring, we are witnessing labor shortages that many have previously warned about. How do we find more nurses, teachers, bus drivers, and those willing to work in the construction trade (e.g., carpenters, plumbers, electricians)? Who will rebuild the bridges and roads in desperate need of repair, especially when we are already at or near full employment and our immigration policy remains a political football? The share of the U.S. population between 24 and 54 who are employed reached an all-time record in March, approaching 81%, so there is not a heck of a lot of additional labor supply to be found here.

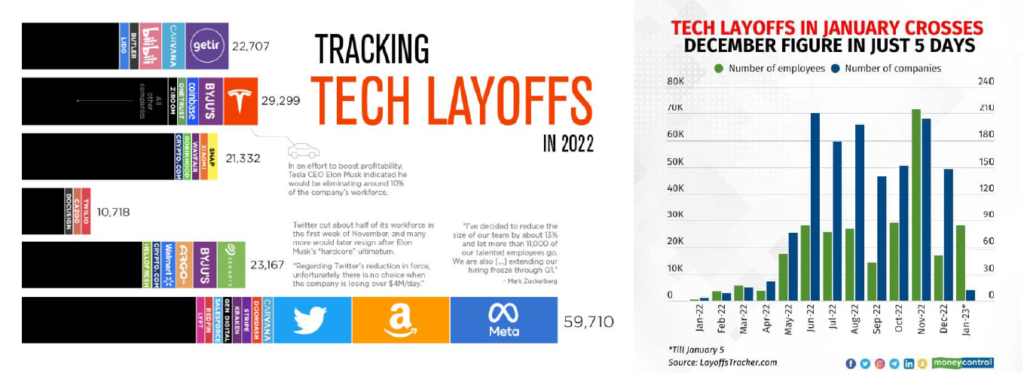

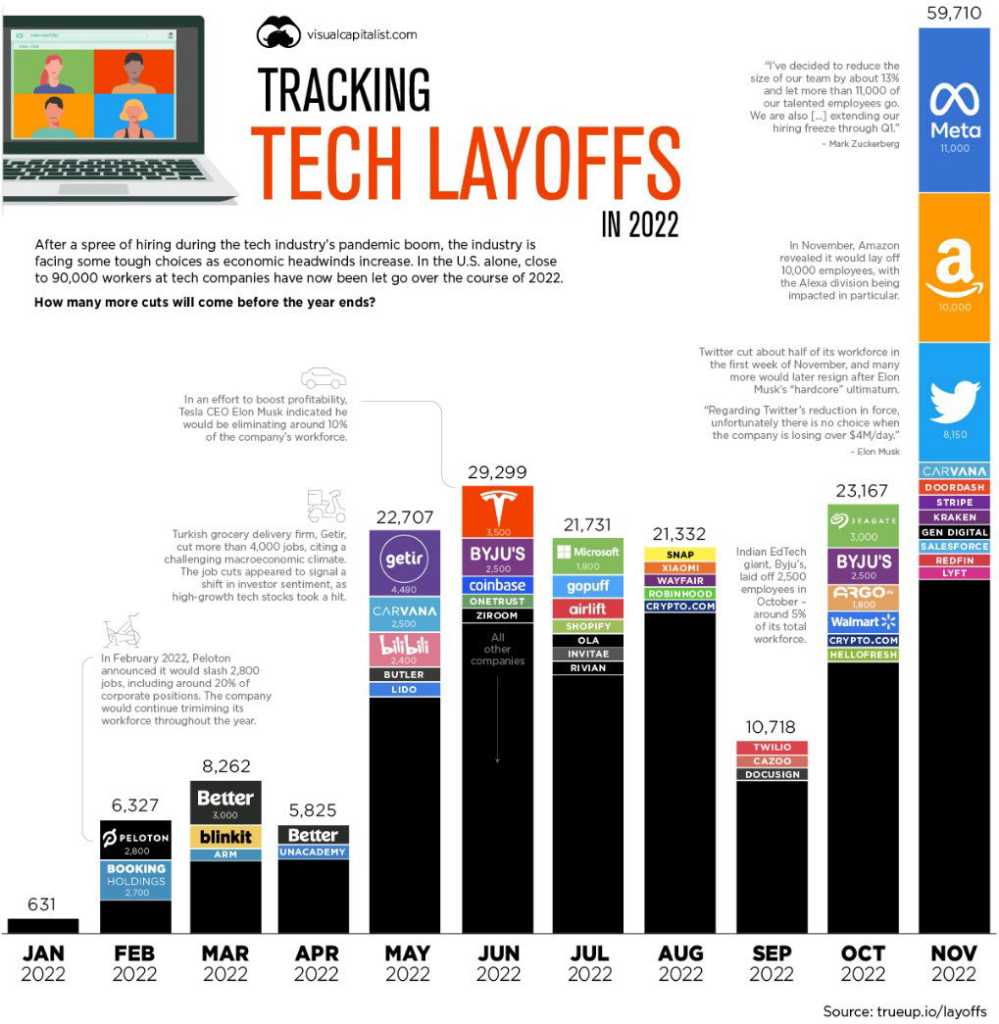

But is not all peaches and cream in the labor markets as layoffs also continue to accelerate, especially in tech, banking, and real estate. Thus far, many laid off workers have been able to find other work, but I am not sure that will remain the case. The running total of layoffs for 2023 based on full months to date is 168,243, according to Layoffs.fyi. Tech layoffs to date this year currently exceed the total number of tech layoffs in 2022, according to their data.

How will AI impact labor markets now and looking forward? This is, perhaps, the most significant uncertainty surrounding employment over the coming years and remains to be seen, of course, but in the meantime, I am relieved that both business school faculty members and managers of financial services firms are not likely to be replaced, at least for a little while.

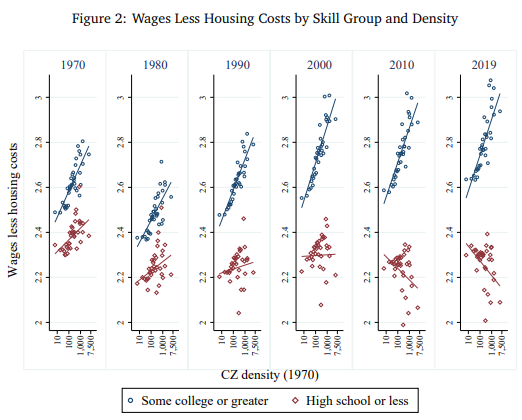

So, why are so many Americans sour on the economy when labor markets remain reasonably robust, and the stock market continues to hold its own?

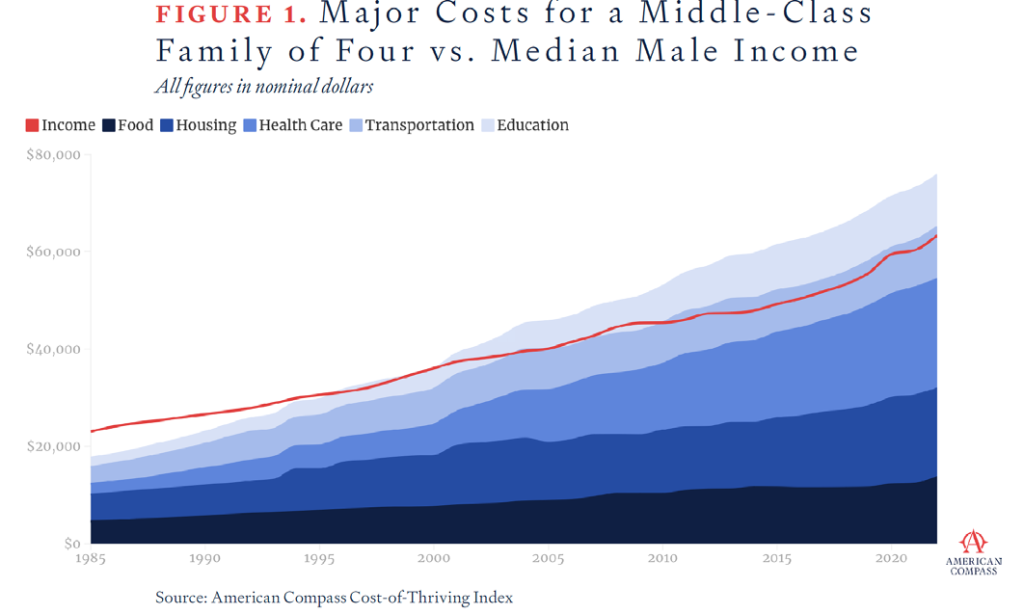

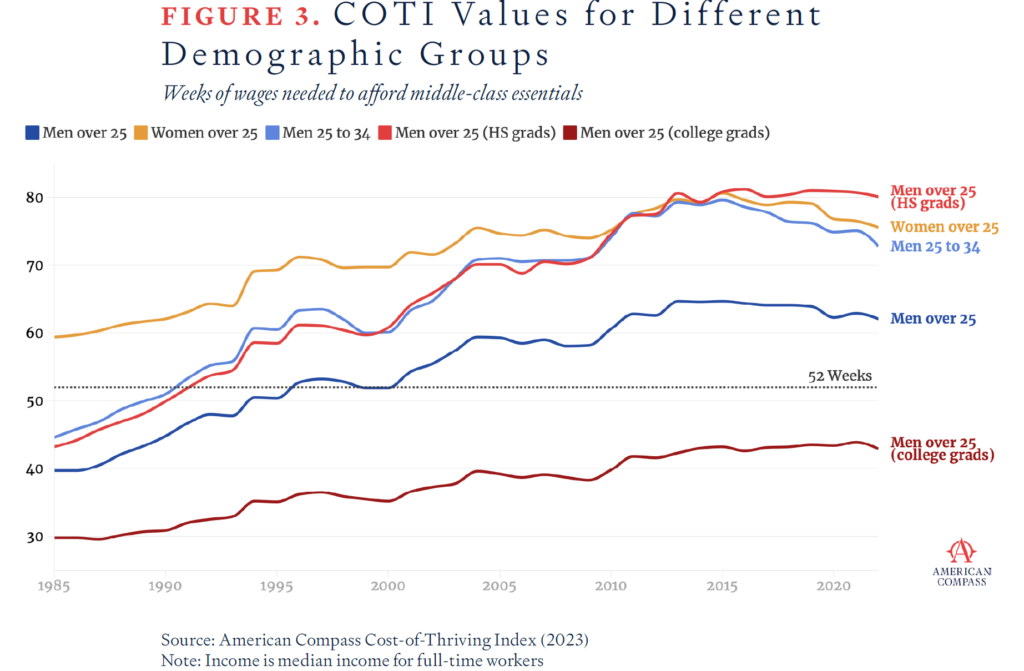

I recently came across some data, released by a conservative think tank (please forgive me, liberal friends), American Compass, and an index it created and labeled, the “Cost of Thriving Index” (COTI) Essentially the index begins with a simple foundational premise, that households must prioritize five sets of goods: food, housing, health care, transportation, and higher education, a sort of modern-day take on Maslow’s hierarchy of needs.

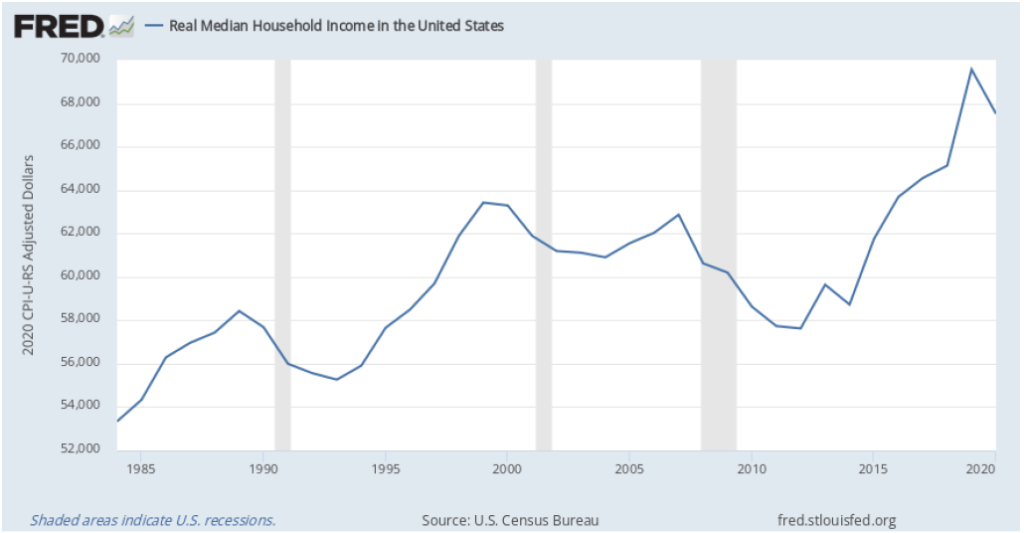

The COTI strives to measure how the median American family is doing in terms of its ability to afford these goods, by looking at the cost of these five items back in 1985 versus today, comparing them with the median wage someone 25 and older and working full-time would earn, and finally, how many weeks it would take for that wage earner to pay for them. The data and conclusions are sobering, but informative, with two pictures communicating a thousand words.

Here’s the upshot. In 1985, it took about 40 weeks of work per year to pay for these things, giving families room to enjoy other consumer goods and luxuries. And today? It takes more than 62 weeks to afford these same costs. You don’t need to be an expert in the Gregorian calendar to realize the issue. The bottom line is that the median American family simply cannot afford what one would consider life’s necessities on a single middle-class paycheck.

For years, I have written about wealth inequality, the differential between the “haves” and “have-nots” Those with assets – principally, equities, bonds, and real estate – have become richer and richer, creating a wider disparity between themselves and the middle class. So, perhaps the declines in stock prices (since the beginning of 2022), fixed income securities, and more recently, commercial real estate values, along with the substantial job losses in technology, banking, and real estate represent a sort of “richsession” as several publications have described it, a sort of rebalancing, if you will. Blue collar jobs in trades, services, hospitality, and leisure continue to thrive, unions are gaining more traction, and government relief programs, including eviction moratoriums and expansion of rent control (see below), have expanded significantly in recent years, consistent with the thesis.

Either because of, or in spite of, political divisions and broad economic forces (read: wealth inequality), local, state, and our D.C.-based politicians seem eager to promulgate one housing related policy after another, generally benefitting renters at the expense of landlords or property owners

I have predicted for years that the most fundamental premise that “there are more tenants than landlords who vote” and housing has become increasingly unaffordable would result in increased expansion of rent control and inclusionary zoning, along with greater rights afforded tenants facing evictions. According to the National Low-Income Housing Coalition, 32 states and 73 municipalities have passed new tenant protections, just since January of 2021.

• National “Renters Bill of Rights”: Almost right on cue, President Biden rolled out a proposed ‘Renters Bill of Rights’ in January as a potential push for federal rent control. Not surprisingly, these efforts have been spurred by the Progressive wing of the Democratic caucus, though it remains to be seen whether the push will result in actual legislation or formal policy change. I suspect it is mostly window dressing and no substantive new national policy measures are forthcoming. After all, for certain types of FHA financing, restrictions are already placed on landlords, generally requiring that units be rented only to tenants satisfying certain income tests. And states are, for better or worse, promulgating their own regulations. For example, the Wisconsin and Economic Development Authority and Pennsylvania Housing Finance Agency agreed to cap annual rental increases to 5% per year for federal- or state-subsidized affordable housing.

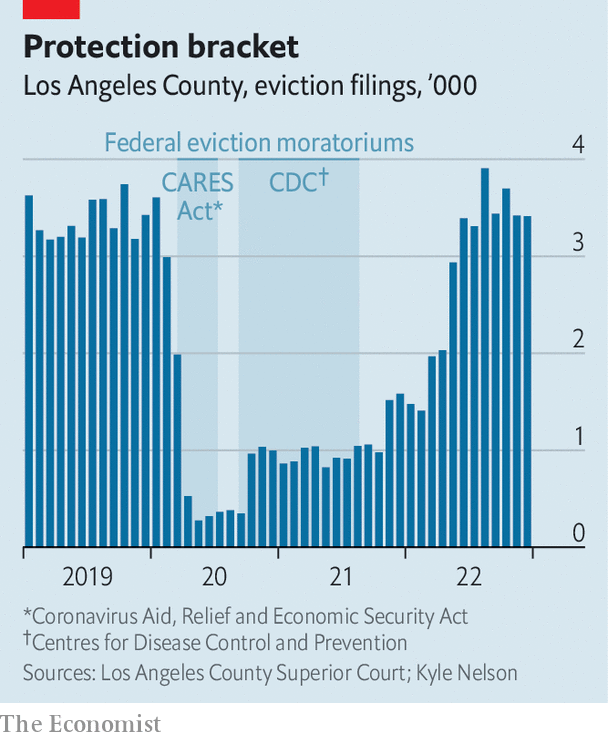

• End of Covid-related eviction moratoriums…or not: One week before they were set to expire, the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors extended by two months its tenant protections against eviction for those impacted by COVID-19, while also approving the establishment of a $45 million relief fund for small landlords who have been unable to collect rent from some tenants. At this point, the last phase of Los Angeles’ rent eviction moratorium will end in June 2023. Imagine that. The end of June, months after President declared the national Covid emergency over, and months after every other state had already lifted its eviction restrictions. Understandably, the extension was met with anger from property owners, while The Apartment Association of Greater L.A. (AAGLA) filed a lawsuit against the city to overturn and stop enforcement of the new ordinances that make it more difficult to remove tenants as well as penalize landlords for raising rent.

One ordinance in question stipulates that at least one month’s rent be past due before initiating eviction proceedings. The other forces landlords to pay relocation fees if rent is raised by at least 10 percent or by five percentage points over the rate of inflation, whichever is lower, and results in a tenant’s displacement. That includes paying three times the fair market rent of the unit plus $1,411 in moving costs. Call me a cynic, but I don’t think AAGLA will get much traction in the Los Angeles Superior or local District Courts.

• New York rent regulations upheld by federal appeals court: In New York, rent regulations and restrictions were upheld by federal appeals court, supporting decades old policy impacting about one million apartments. In short, the Second Circuit Court of Appeals rejected a challenge by landlords to state law passed in 2019, which made it much more difficult for landlords to free up apartments to achieve “market” rent. As other courts have found, the Second Circuit determined that rent regulations are not an intrusion on property rights or an unconstitutional taking and that legislatures have broad authority to regulate land use without running aground of the Fifth Amendments bar on physical takings. The Court reasoned that landlords are not restricted from receiving market rents “in perpetuity.” In my view, the Courts consistent justification of restrictive rent policies under land-use guidelines is misleading and another example where judicial ends justify economic means. But I call B.S. on this perspective, since it is not the “land use,” which is at issue, but rather the income stream that is derived from that same use. But realizing that judges allow desired outcomes to influence judicial reasoning and rulings is about as shocking as it was to learn that George Santos wasn’t Jewish or an astronaut.

• Rent-related proposals in Colorado, Massachusetts, and Maryland: As indicated above, several states have proposed legislation to protect tenants or ostensibly increase the affordable housing stock. In Colorado, a bill was recently introduced which would give local governments a right of first refusal to purchase multifamily properties before private parties so long as they commit to rent out units for affordable housing. In another measure, which has passed the State House of Representatives, statewide rent control preemptions would be revoked, allowing local communities to establish their own rent-related policies. In Boston, the City Council passed the mayor’s proposal to cap rent at six percent plus the increase in the Consumer Price Index, up to a maximum of 10 percent. However, state lawmakers still need to strike down statewide rent control preemption. Finally, in Maryland, two major counties appear poised to pass rent controls. In Prince George’s County, which surrounds the eastern half of Washington, D.C., county officials just pushed through a measure temporarily capping annual rent increases at three percent. In neighboring Montgomery County, lawmakers are considering two proposals that would cap rent increases at either three or eight percent. Have your popcorn ready.

• Los Angeles’ Measure ULA Tax: The ULA Tax is a new real property transfer tax that was recently approved by voters in Los Angeles. The tax went into effect on April 1st and will be levied in addition to existing city and county documentary transfer taxes. The ULA Tax will be 4% on all real property sales (commercial and residential, whether single- or multifamily) priced between $5 million and $10 million, and 5.5% on real property sales priced or valued at $10 million or greater. You do the math. It’s an extraordinary and very significant tax, which will very consequently impact the industry, reducing property values, transaction volumes, and ultimately, the economics and construction of new housing.

In addition, it’s inherently absurd, as it ignores the amount of equity one might have in a home, as it is based solely on the sales price. Therefore, someone selling a $4.5 million piece of property pays no tax, even if the property has no debt, while someone selling a $5 million asset with a $4.5 million mortgage pays the full tax. Finally, while the revenue raised by the new tax is intended to be used to fund affordable housing and tenant assistance programs, I assume it will make nary a dent on homelessness or housing affordability.

And, as always, there are always other interesting economic, financial, and real estate related tidbits that grab my attention

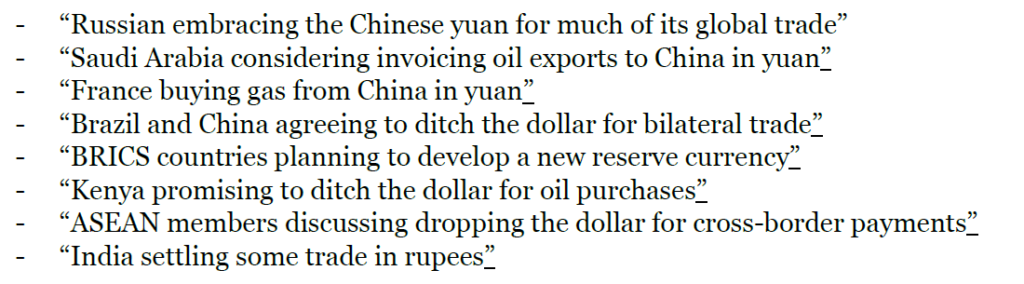

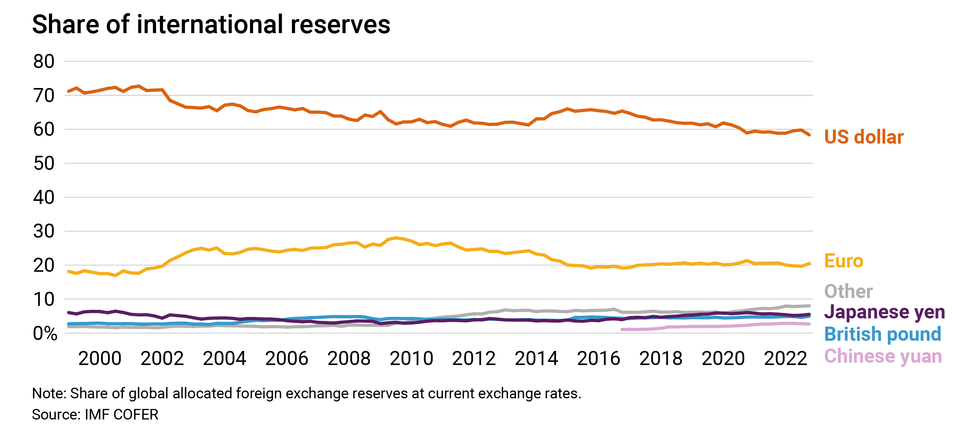

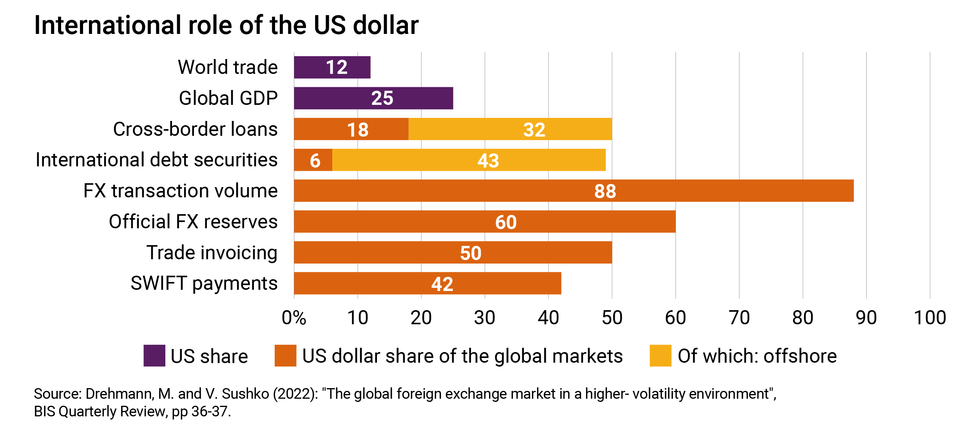

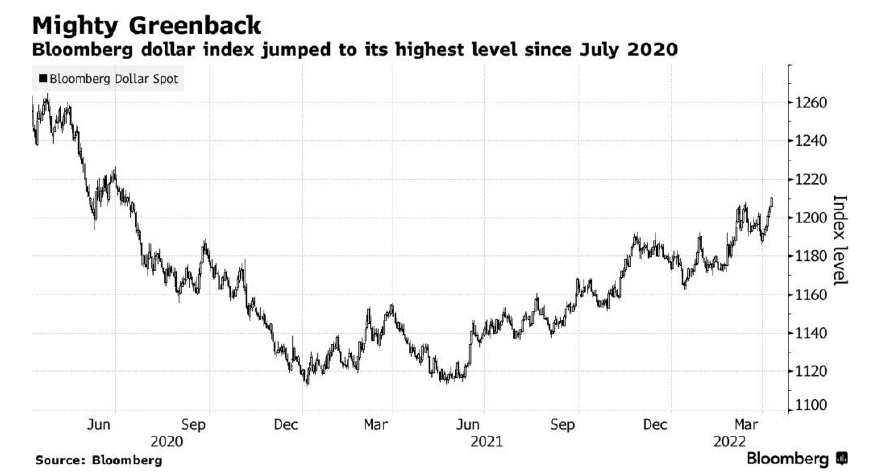

• Rumors of the U.S. dollars demise are greatly exaggerated. Every now and then, a story or three emerges about how this country or that one seeks to diversify away from the U.S. dollar, kicking off frenzied concerns about the inevitable end of dollar dominance. Naturally, these stories provide fertile ground for gold bulls, cryptocurrency promoters, and perhaps just your regular run-of-the-mill grifters to stoke fear about the dollar’s imminent (or just ultimate) death and the potentially catastrophic economic consequences that may follow. Lately, and not surprisingly, perhaps, given the political climate and ability to stoke fear via social media, there have been more than a few such headlines:

Doomsayers offer numerous reasons for the dollar’s inevitable demise, from China’s increasing local and global influence, America’s stagnant economic growth, chronic fiscal deficits, irresponsible monetary expansion and growing debt burden, trade disputes, etc., to challenges posed by potentially disruptive technologies like central bank digital and cryptocurrencies. However, it is my strong view that such rumors are just that, rumors, and that the dollar remains incontrovertibly dominant in global trade and finance, now and looking forward, if not a bit less dominant than before, perhaps Lebron James in the twilight years of his career.

Specifically, while the dollar’s share of central banks’ $12 trillion foreign exchange reserves has declined since 1999, it is still almost twice that of the euro, yen, pound, and yuan combined and the same as it was a decade ago. Its nearest competitor, the euro, accounts for barely 20% of central bank reserves (compared to the dollar’s 58%), followed by the Japanese yen and Chinese yuan at 5% and 3%, respectively.

Moreover, China also employes strict capital controls and foreign investment quotas, as well as a complex system that manages onshore trading and influences offshore yuan activity, so until and unless such controls and heavy-handed management end, I cannot see the yuan replacing the U.S. Dollar anytime soon.

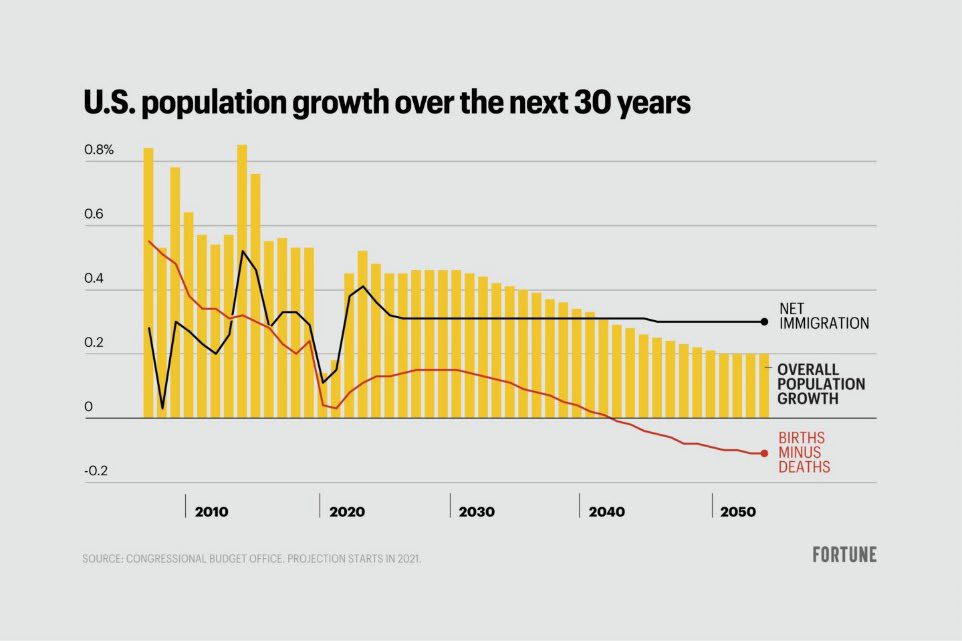

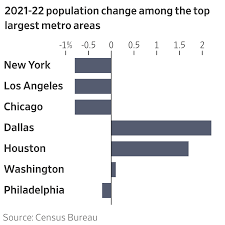

• While the exodus from big cities slowed in 2022, the U.S. population is expected to decline shortly after 2040 if current trends hold: In recent years, I have written extensively about demographic changes and how they might impact real estate markets looking forward. Broadly speaking there have been a few significant shifts in U.S. demographics.

One, folks are getting married later, if at all, and having fewer children. That is a persistent trend throughout the developed world, largely deflationary, and arguably irreversible no matter what incentives might be provided. Let’s face it, feeding, housing, clothing, and educating kids has gotten too darn expensive, especially in populated cities. And without a significant shift in immigration policy, projections indicate that the U.S. population will begin to decline in about 20 years, just like Japan, and more recently, China.

The second was a significant move back to urban cores beginning about 10 to 15 years ago, following decades of “white flight.” However, this trend reversed course again as a result of Covid, when people relocated to less dense suburbs and/or were able to work remotely and moved, if just temporarily. The third has been the relocation of households from the coasts to less expensive inland markets, resulting in the Californication (or NewYorkification) of several cities, from Phoenix to Atlanta, from Reno to Nashville, from Boise to Miami. In fact, California saw some 700,000 residents, net, leave the state following Covid, a figure matched only by New York, which experienced similar population outflows.