“If all the economists were laid end to end, they’d never reach a conclusion.”

-George Bernard Shaw“Prophesy is a good business, but full of risks.”

-Mark Twain

First and foremost, on behalf of the entire Clear Capital team, allow me to express my very best wishes to each of you and your families for a happy, healthy, and prosperous 2020. We had a busy, productive, and successful 2019, and we hope to carry this momentum into the New Year and beyond.

Over the past year or two, I have quoted everyone from Jerry Garcia to PT Barnum to Rod Serling as I have endeavored to reconcile the seemingly contradictory and confounding data points that the economy, investment markets, and national and geopolitical environment have provided. Yet, despite all the uncertainties and risks, nearly every investment vehicle – equities, bonds, commodities (e.g., oil, gold), and residential and commercial real estate – performed very well in 2019. The S&P 500 returned nearly 29%, its best performance since 2013, and all 11 sectors comprising the Index finished in the black. Oil, gold, and bonds achieved double-digit returns.

Even U.S. Treasuries, which tend to decline when risky assets rally, generated positive returns during the year, as the Fed cut rates three times. And if you had any doubt how good a year 2019 was, consider that Greek 10-year bond yields dropped in half (to 2.05%!). So instead of PT Barnum, perhaps I should quote Pangloss, as it truly seems to be “the best of all possible worlds,” at least when it comes to recent investment returns. Significant liquidity and low interest rates are indeed formidable and impactful dance partners.

Taking a longer view, U.S. stocks returned 252% during the last ten years, and for the first time, an entire decade passed without a bear market or recession. That is not to say that there have not been some fireworks along the way. During the last decade we experienced six separate market corrections (declines of at least ten percent), the May 2010 “flash crash,” Europe’s sovereign debt crisis (2011-2012), the devaluation of the yuan, the Arab Spring, global trade wars, Brexit, Trump and impeachment, negative interest rates and inverted yield curves, riots in Hong Kong, the implosion of WeWork, Australian wildfires, a couple royal weddings (pre-Megxit!), the closure of tens of thousands of brick-and-mortar retail locations, and even a total solar eclipse. The financial markets more than withstood each.

However, plenty of risk, uncertainty, and conflicting data points remain. For example, while labor markets may be buoyant, retail sales strong, and inflation tame, domestic and global GDP growth is tepid and manufacturing data mixed, while trade tensions persist, the federal deficit topped $1 trillion for the first time in seven years, and even more brick-and-mortar retail locations seem to close each week. Furthermore, the Fed has signaled that no additional interest rate cuts are in the cards, at least for the near future. Washington remains as dysfunctional as ever, with impeachment proceedings and the fallout from the recent bombing in Iran increasing macro-level uncertainties.

My biggest concern is that investors, desperate for yield in a very low (and in some cases, negative) interest rate environment, have become complacent, and may not be properly pricing risk. The reality is that it is easier to find Sasquatch or political compromise than yield these days, and some investors seem to be ignoring macro-level risks. The Volatility Index (VIX) remains at near-term lows, while the price-earnings ratio of the S&P 500 has increased to more than 24 times earnings, up from 15 at the end of 2018. A mere five companies (Apple, Microsoft, Google/Alphabet, Amazon, and Facebook) make up nearly 20% of the entire market capitalization of the S&P 500, an unprecedented level of concentration. The ten largest stocks in the Index account for nearly a quarter of its value. Interest in and capital flows to secondary, tertiary, and in some cases, quaternary (first time using that word, best I can recall) real estate markets have increased significantly, reaching record highs.

So what were the most significant events from 2019 that impacted real estate (and other) markets? Which might have the greatest impact on markets looking forward?

In the spirit of the cinematic awards season, here are the nominees for “Most Impactful Event on U.S. Commercial Real Estate Values” from 2019, in no particular order:

- Implosion of WeWork (Adam Neumann, Producer): With 528 locations in 111 cities across 29 countries and over 12.2 million square feet of leased space, WeWork has been an extremely active player in core office markets. For example, WeWork is now the largest private tenant in all of New York City. The company will clearly be consolidating and cost cutting this year (and perhaps beyond), and many office assets and markets will be affected, though the ultimate fallout remains to be seen.

- Sharp decline in foreign investment activity (Numerous Countries, Producers): In the first half of 2019, cross-border commercial real estate investment dropped 54% from the prior year, reflecting global uncertainty and capital constraints. In fact, cross-border investors became net sellers of U.S. commercial real estate in the second quarter of 2019 for the first time in seven years. One need only look at New York City where nearly half of the Manhattan luxury-condo units that have come onto the market in the past five years are still unsold, according to The New York Times, as developers bet big on foreign plutocrats—Russian oligarchs, Chinese moguls, Saudi royalty—looking to buy their second (or seventh?) homes. Those bets appear to have been losing ones. While 2020 should be stronger as the U.S. remains a safe(r) haven and is still growing faster than other regions, I doubt foreign investment in the next year or two will match the substantial activity we witnessed in the latter part of the last decade. Reduced foreign investment will affect nearly every property type, mostly core assets in primary markets.

- Fed’s reversal on interest rates (Jerome Powell, Producer): In 2019, and to the surprise of many, the Fed lowered rates three times, reducing the Fed Funds rate 75 basis points (to 1.50%), the last time in October. However, while the Fed has signaled that no further rate cuts are in the cards for at least the near term, I recently read that UBS predicts that there could be as many as three additional rate cuts in 2020, in light of slowing economic growth and the impact of trade tariffs. Others say the Fed will stand down in an election year. We shall see.

- Passage of statewide rent control in California, Oregon, and New York (Gavin Newsom, Kate Brown, Bill de Blasio, Producers): As I have described in prior updates, local and state governments have been pulling different levers in order to address housing affordability. Three states implemented statewide rent control during the year, and more may soon follow. While these efforts are destined not to succeed, in my view, I do not expect politicians to pursue alternative (and probably more effective) approaches any time soon. They lack the resources, both financial and political, to do so.

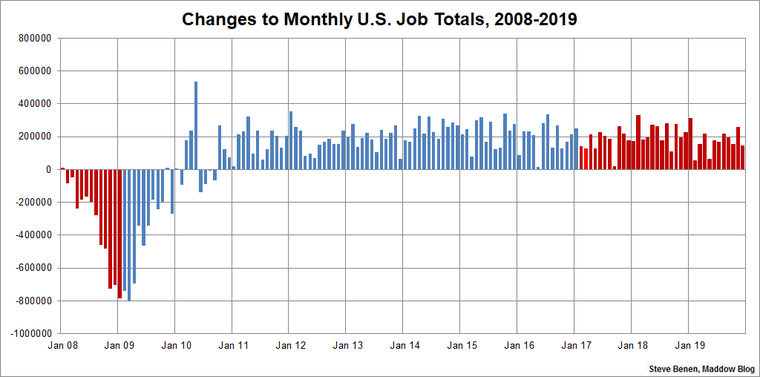

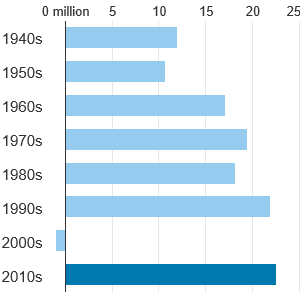

If I had to add one other nominee to the aforementioned list, it would have to be the 2.1 million jobs that were added during 2019. However, these results were not a 2019 phenomenon as we have now witnessed ten years of job gains, including 2.8 million new jobs in 2018. Regardless, such a noteworthy data point at least deserves an “honorable mention.”

Unfortunately, Price Waterhouse Coopers was not available to count ballots and determine the victor, so we will have to declare a four-way tie for now. Perhaps a clear winner will emerge sometime this year or next.

So, with all this being said, what should one expect in 2020?

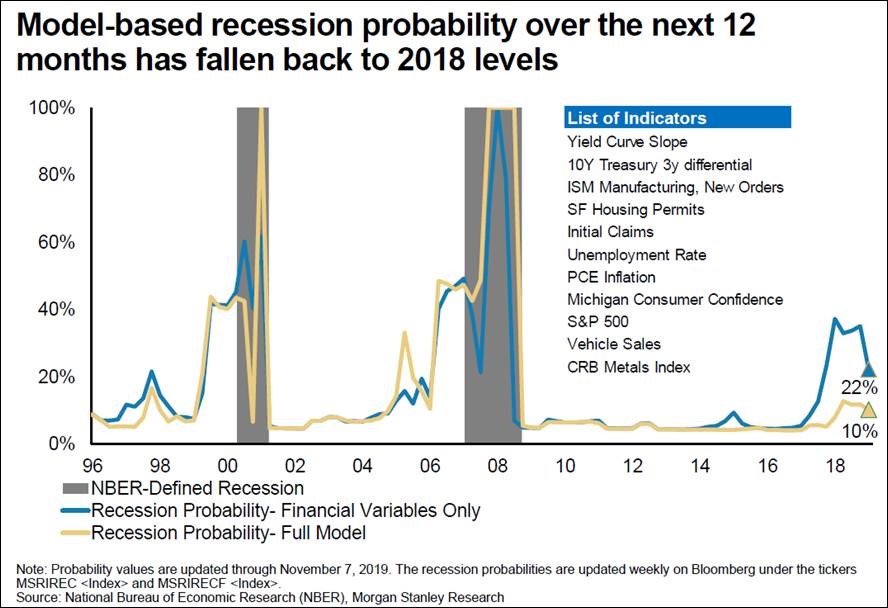

I recall someone telling me once that when there is broad consensus about something, it is likely that something else altogether different will occur, though I am not sure if there is any academic research to support this platitude. However, with U.S. equity markets now having experienced the longest and least volatile bull market in history, and nearly every economic pundit not anticipating a recession this year (or even into the first half of 2021), one with a longer view of history has to be wary. Recession fears have significantly abated, and the UCLA Anderson forecast believes there is a less than 20% chance of a recession through the third quarter of 2020, consistent with the model below, courtesy of Morgan Stanley.

While mindful of the dangers of joining any consensus (I would hate to join any club which might have me as a member, to channel Groucho Marx), I tend to agree with the view that a recession this year seems unlikely, simply based on the strong fundamentals underpinning the markets: low interest rates, significant liquidity, low unemployment, and tame inflation. The $3.4 trillion in cash sitting on the sidelines (highest level in a decade) remains a downside buffer. I find these two graphs, presented side-by-side to tell the story quite simply. While the S&P 500 has risen sharply, so have cash reserves, measured in part by the growth in assets in Money Market Funds.

As I mentioned in the last quarterly memo, Blackstone recently raised their largest real estate fund (over $20 billion) and Goldman Sachs has reentered the real estate fund game. In fact, real estate fund managers raised over $150 billion in 2019, a record. All that additional equity awaiting investment should also prop up commercial real estate values, or at least create some downside cushion in the event of a downturn or significant decline in asset prices.

However, investor and market psychology can turn very quickly, and the broad complacency extant in the markets is concerning, given the uninspiring growth in GDP here and abroad, recent market returns and valuations, the continued reshaping of the retail landscape, and substantial political and geopolitical risks. Investors are well served by reducing leverage and maintaining adequate liquidity in markets like these, and I think such an approach is especially prudent today.

Meanwhile, the most significant issue in residential real estate will continue to be “affordability,” as prices and rents continue to rise and outpace inflation

The statistics surrounding affordable housing are sobering, if not staggering. The U.S. has a shortage of at least seven million homes for the country’s lowest income households, and less than 40 affordable homes exist for every 100 extremely low-income households. Since 1990, the market has lost more than 2.5 million low-cost rental units and rent growth has substantially outpaced wage growth and inflation. For example, during the last decade, rents in Los Angeles and nationwide increased roughly 65% and 36%, respectively, outpacing growth in household income (36% in Los Angeles, and 27%, nationwide). Homelessness plagues nearly every city, and here in Southern California, one need not look very hard to see the pervasive impact of constrained housing supply.

The underlying causes are several-fold, but the challenges of building in supply-challenged markets remains the most significant impediment to greater affordable housing. Developers consistently rank NIMBYism (“Not in My Backyard”) as the largest barrier to construction. The largest markets where building is “easiest” include Cleveland, Milwaukee, Chicago, Dallas, and Houston. To be candid, we have experienced the impact of easier entitlements in our Dallas/Fort Worth portfolio, as projected rental growth has been lower than projected, though I anticipate supply growth will moderate substantially over time with increasing land acquisition and building costs, and rents will rise substantially in time. The low inventory of homes for sale nationally sits at its lowest level in 37 years (adjusted for changes in population), and only adds to the demand-supply imbalance.

Not surprisingly, many California markets rank highest in difficulty of adding supply. It has gotten so bad that the private sector has had to shoulder more of the burden. Apple recently announced that it is committing $2.5 billion to affordable housing in the Bay Area, following the lead of Alphabet/Google and Facebook, which have similar, though more modest, $1 billion commitments. Microsoft has committed to invest $750 million to Seattle housing. However, a lack of capital is merely one impediment to adding to the affordable housing stock. It is incumbent that local and state politicians simplify zoning regulations, reduce bureaucracy, and accelerate the entitlement process to promote construction and increase housing supply. Meantime, the affordable and workforce housing shortage is not limited to primary markets like the Bay Area or Seattle. Supply-constrained markets are spread throughout the country. Secondary and tertiary markets such as Austin, Charleston, and Raleigh are also experiencing a significant need for more supply as residents struggle to find affordable housing.

Rising construction costs are not helping the cause, of course, nor the fact that most multifamily housing building during the last decade was Class-A, and not targeted towards working-class households. Fortunately, construction material costs remained fairly stable last year, despite the ongoing trade tensions. Lumber prices actually dropped, declining about 10%, after an 11.2% rise in prior year. Gypsum (wallboard) costs dropped 8.0%. However, the persistent, longer-term trend has been quite different, and a shortage of construction labor and contractors (both general and subs), coupled with glacial approval processes are not helping the cause. Lenders remain bullish on apartments and seem more than willing to fund new construction, but prospective projects are getting harder to pencil, and lower interest rates can only do so much.

The net result is that multifamily rents will continue to increase, though at a slower pace. Through the third quarter of last year, rents in 79 of the 82 markets tracked by REIS experienced increased rents. Effective rents nationally grew by one percent and 0.5% in the third and fourth quarters of 2019, respectively, the lowest growth rates in more than two years. Net absorption of 21,500 units was less than half of that experienced in the third quarter, and 30,159 units were completed, about sixty percent of third quarter activity. Overall occupancy among multifamily assets nationally has remained between 95 and 96%.

Secondary, tertiary, and even quaternary markets will be the primary beneficiaries of increased housing costs, the sort of markets Clear Capital is focusing on to source potential acquisitions

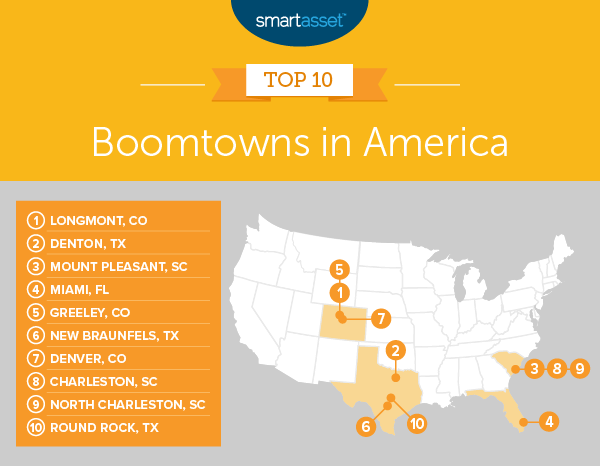

In 2019, the best performing multifamily markets, measured by annual rent growth, did not include a single core or primary market. Instead, cities like Midland-Odessa (TX), Pensacola (FL), Las Vegas, Phoenix, and Wilmington (NC) dot the list, locales with strong employment and job growth. As discussed many times before, companies are relocating to these markets from more costly primary markets, and employees follow suit. Another source I read identified “Boomtowns in America,” based on the fastest-growing cities in terms of population and economic growth. The largest markets making the list were Miami and Denver, but Longmont, Colorado is the BCS Champion of this particular list, with appropriate apologies to LSU’s Tigers.

In mid-November, the LA Times published an article, “California Exodus Makes Waves: Boise’s mayoral race is a referendum fueled by those from the Golden State.” One sentence from the article captures the tension between core and secondary markets: “Candidate Wayne Richey ran on a very simple platform: Stop the California Invasion.” One local Boise newspaper article likened California transplants to a “plague of locusts,” putting things in biblical terms. While California’s experiences record low growth rates, population outflows, reduced household formation, and lower immigration, tertiary markets like Boise and Longmont are the principal beneficiaries (or perhaps the opposite, if one thinks locusts a nuisance) of the trend.

While these smaller markets may present additional risks, the vacancy rates in secondary and tertiary markets are actually less than one percent greater than vacancy seen in core markets. With these risks, however, come stronger cash flows. Cap rates average 150 to 200 basis points higher in secondary and tertiary markets than in primary markets. Not surprisingly, more than half (55%) of multifamily properties bought in 2019 were located in secondary and tertiary markets, up from 43% ten years ago. While apartment vacancy in core markets has dropped to 3.4% from 5.4% a decade ago, the decline even more pronounced in secondary and tertiary markets, from 7.2% to 4.8%. Obviously one has to be especially mindful of the risk-reward tradeoffs and perform due diligence accordingly when evaluating acquisition opportunities in such markets.

With all of this being said, it will come as no surprise that the faster-growth secondary and tertiary markets are where we are evaluating potential acquisition candidates, in our belief that most opportunities in core markets simply do not pencil.

But finding value in any market – primary to quaternary – remains no simple task

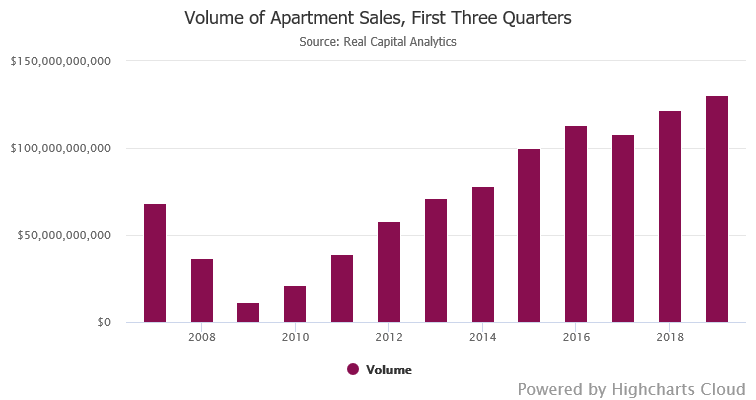

With so much investable cash sitting on the sidelines, and investors searching far-and-wide for yield, it should come as no surprise that the first three quarters of 2019 witnessed higher multifamily sales volume (nearly $131 billion) than any comparable period in the last ten years. REITS were particularly active, having spent $7.1 billion on apartment acquisitions, the most they have acquired since 2014 and more than all of what they spent in 2018.

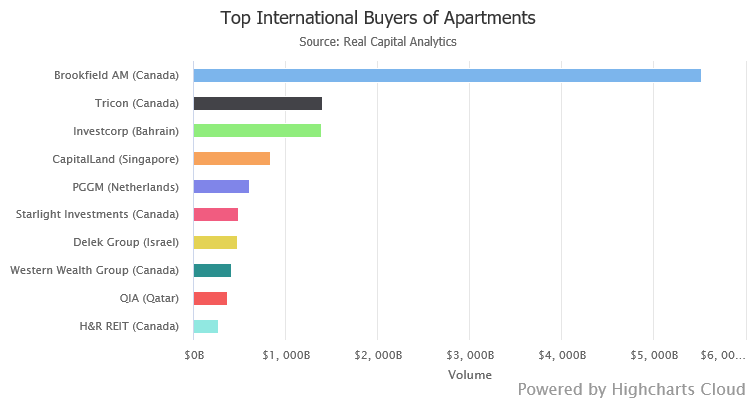

Meantime, while overall volume of cross-border investment in U.S. real estate has declined and slowed, as described above, apartments remain popular destinations for foreign capital. Cross-border investors spent over $16 billion on apartment property acquisitions during the 12 months ending in June of last year, a 10% increase. The biggest buyers, by far, have been Canadian investors.

The net impact is that substantial capital is seeking opportunities in the multifamily space, and finding value is no easy task. Each week the Clear Capital underwriting team is underwriting between 20 and 25 opportunities, in markets across California, Arizona, Colorado, Utah, New Mexico, Texas, Ohio, and Florida. We hope that our casting a wide net in markets we find attractive will ultimately pay dividends.

Low interest rates should persist well into this decade, meaning the chase for yield will continue

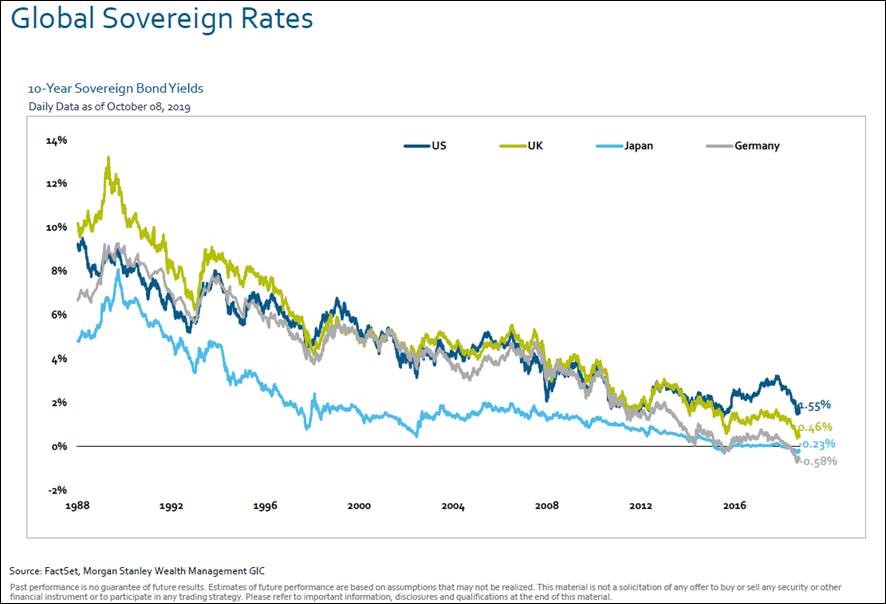

If a single picture can tell a thousand words when it comes to what has happened with interest rates both here and abroad over the last decade, perhaps this is it.

While yields on 10-year U.S. Treasuries were volatile in 2019, they ended the year at 1.92%, as compared to 2.66% at the start of the year, and 1.68% at the start of the fourth quarter. In mid-December, after reducing interest rates at its three previous meetings, the Fed voted unanimously (10-0) to leave the Central Bank’s benchmark rate where it presently stands (1.75%), and indicated that it would take an indefinite breather on reducing rates further.

The Fed’s statement comes as no surprise, given asset values, recent market performance, and low unemployment. On the other hand, GDP growth remains uninspiring and inflation remarkably subdued, with the CPI-U up a modest 2.3% in 2019 (0.2% in December). Perhaps this is why UBS is predicting that the Fed could lower interest rates three times in 2020, in contrast to other banks and prognosticators. Meanwhile, the previously inverted yield curve has quietly “uninverted,” another indicator that perhaps a recession is indeed not in the cards.

The biggest question mark is whether the Fed can use its usual monetary policy toolbox to combat a recession, should one arise. After all, the Fed already holds about $3.8 trillion in assets which still includes bonds purchased to stimulate the economy following the 2008 global financial crisis. As mentioned in my last memo, the Fed has recently had to purchase short-term treasuries and inject cash to alleviate reserve shortages in the banking system. How many bullets does the Fed have left in its arsenal and how effective will those bullets be in the event that we experience a meaningful downturn? That remains to be seen.

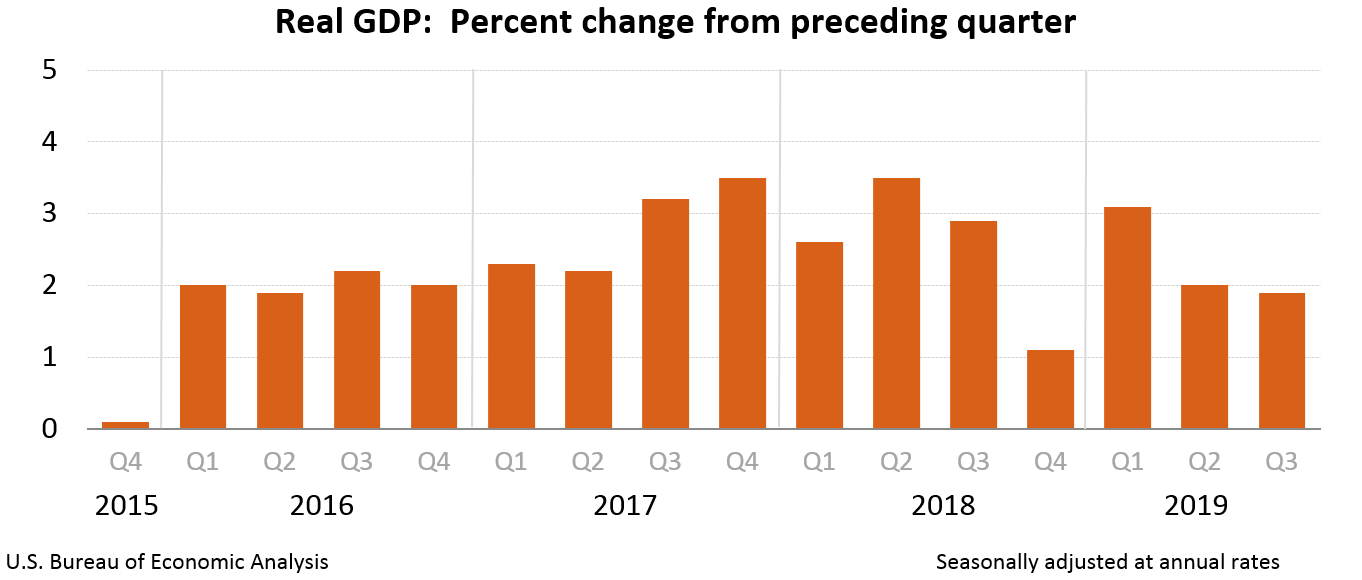

As mentioned, these low interest rates are, in part, a byproduct of uninspiring GDP growth, here and globally, so the message is mixed

Real U.S. economic growth slowed in the third quarter of 2019 to a whopping 1.9%, reflecting the impact of the tariffs and a decline in consumer spending, which was up 2.9% (versus 4.6% in the second quarter). Keep in mind that consumer spending typically constitutes 70% of GDP growth.

Meantime, I recently read an interesting piece from Stanford’s Institute for Economic Policy Research, which has created a “World Uncertainty Index,” a broad metric (143 countries) to measure “global views on uncertainty” in the view that “uncertainty” creates a drag on investment and economic expansion. Their most recent results and conclusions align with those of the IMF, that global economic growth will be 3.0%, the slowest growth rate since the end of the global crisis and down 0.3% from forecasts made earlier in 2019.

But the employment picture here in the U.S. continues to shine…mostly

The U.S. added 145,000 jobs in December, marking the longest stretch of annual increases in employment in 80 years, a truly remarkable data point. An alternative measure, which captures the “underemployed” and those “marginally attached to the workforce,” the U-6, fell to 6.7%, the lowest figure on record since 1994. Ironically, the share of adults working or looking for work held steady in December at 63.2%, but remains well below the peak of 67.3% in 2000. In one dark spot, wages advanced only 2.9% from a year earlier, the smallest annual gain since July 2018. This most recent data on wages is a little sobering because October’s wage growth (3.8%) eclipsed the average fixed rate, 30-year mortgage rate of 3.7% for the first time since 1972. However, that achievement sure did not last long.

In any event, this conundrum, an economy experiencing more than “full employment” and yet, minimal real wage growth, will continue to affect everything from multifamily rents to politics to GDP.

Job Growth by Decade

One other employment tidbit I read recently is that the most common occupation for American males lacking a college degree is as a driver – truck, taxi, bus, and/or Uber/Lyft – jobs which may ultimately be replaced with Level 5 autonomy (self-driving cars). While I suspect this remains at least a decade away, it is at least worth noting as we look into the labor markets of the future.

Of course, I would be remiss if I did not at least pass on a few tidbits about the public sector’s efforts to further regulate housing markets

At the risk of sounding like a broken record (or perhaps a corrupted Mp3 file), here are some noteworthy recent anecdotes from the annals of public sector efforts to further regulate housing markets and tackle the “affordability crisis”:

- In late November, I read an LA Times article, “Rent Fears Scuttle 577-Unit Project,” about how planning officials rejected a high-rise (six story) residential housing project in South Los Angeles because of “gentrification fears” surrounding “market-rate” housing. The project was rejected even as developers made a last-minute offer to designate 63 units as “affordable,” charging below-market rents. In a telling quote, one of the Council members voting against the project said, “If the current residents cannot afford it, we should not build it.” I can certainly appreciate the sentiment, but it essentially ensures that no meaningful housing will be built, affordable or not, without significant financial incentives from the public sector. After all, where is developable, high-density, housing able to be built and needed? Beverly Hills? Keep in mind that the proposed project was consistent with local zoning ordinances, adjacent to two light-rail lines, and therefore “transit-oriented.” It is truly no wonder that Governor Newsom wants to take control of the project permitting process, ensuring that should a project comply with local zoning laws, it must be approved. Stay tuned and have your popcorn ready.

- In early December, the Los Angeles City Council approved a ban on donations from developers, limiting the ability of real estate developers to donate to campaigns of City Council members, mayors, or city attorneys, while the City weighs key approvals for any of their projects, including zone changes or similar issues. Opponents wanted an outright ban on donations from developers.

- A Portland suburb is about to vote on new law that would tax anyone who demolishes a home ($15,000), with funds used for maintenance of local parks. I am not arguing that maintenance of local parks is not important, but it seems far less important than homelessness or the “affordable housing crisis.” Moreover, such taxes may mean less development of new housing, at least on the margin.

I suspect that 2020 will bring fewer headlines regarding real estate regulation than we saw in 2019…thankfully. I suppose this means these memos might be shorter, and that is not all bad. However, let’s not kid ourselves. The longer-term trend towards increased public sector intervention is clear and will be ongoing.

And finally, a few additional data points or newsworthy items worth noting…

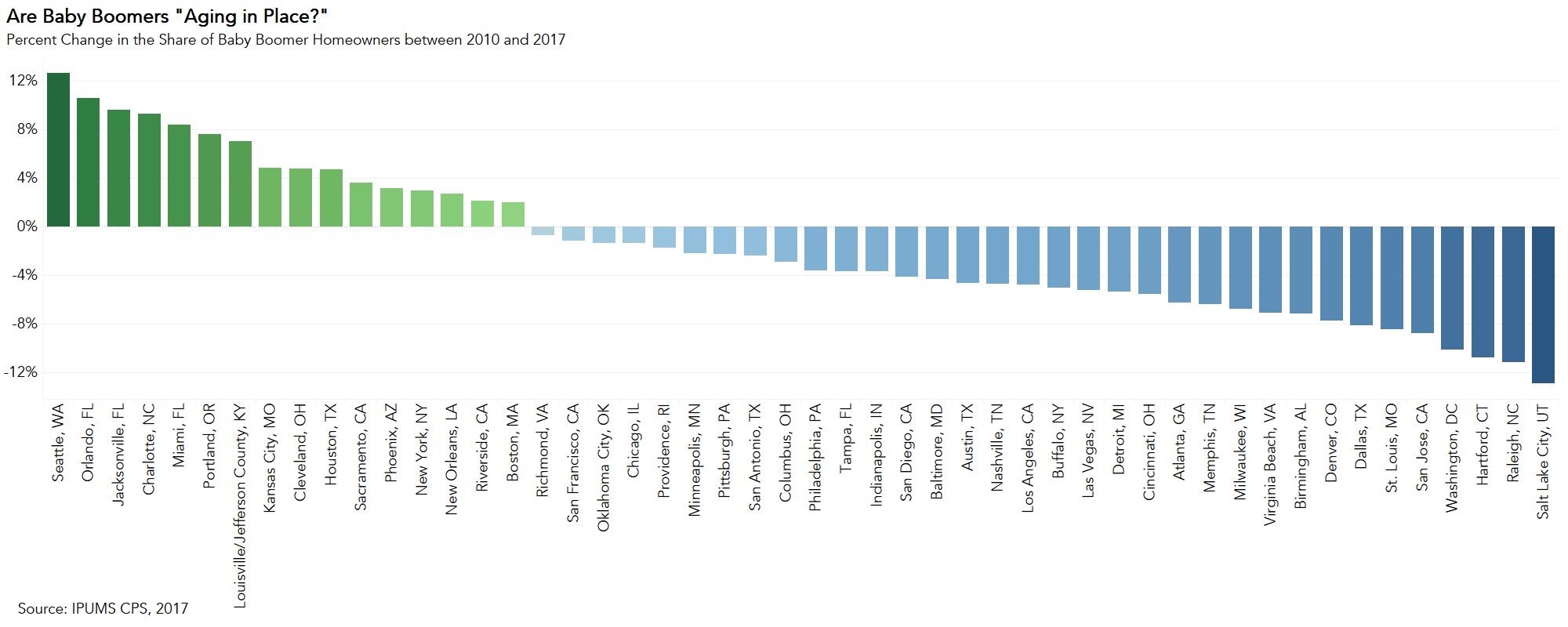

- The Senior Housing market has cooled: While the broad trends appear very favorable for senior housing with Baby Boomers (folks born between 1946 and 1964) representing one in five Americans, the senior housing market has cooled off lately, in part because of technologies allowing seniors to stay in homes longer than ever before (e.g., sensors responding to various medical conditions, flexible housing fixtures). Senior housing occupancy rates dropped in the third quarter of 2019, to 88%, as compared to 90.2% in the fourth quarter of 2014. Meanwhile, a recent article in the WSJ, “OK Boomer, Who’s Going to Buy Your 21 Million Homes,” discussed how aging Baby Boomers are going to need to sell their homes in the coming years, but these homes are not necessarily located in markets or locations where younger families want to buy. According to the article, some 9.2 million homes in the U.S. are expected to be vacated by seniors through 2027 (21 million, in total, through 2037). Hardest hit will be retirement communities in places like Sun City, Arizona, or Delray Beach, Florida, and the Rust Belt, which have aging populations where young people probably do not want to live, all else equal. The precise impacts remain to be seen, but it is an interesting phenomenon worth tracking.

- Apartment sizes have shrunk over the last ten years: As developers build more new apartment buildings in busy urban areas, they are focusing more on studios and one-bedroom units to meet the needs of the market, principally unmarried individuals and childless couples. These smaller units are most commonly found in the urban cores of California, the Northwest, and Northeast. In buildings developed since 2010, new apartments have averaged approximately 940 square feet, down from roughly 1,000 square feet built previously. In California, the “shrinkage” has been most dramatic (858 square feet from 974 square feet).

Even if it were not an election year, 2020 should provide plenty of interesting story lines. The biggest question is whether the markets and economy can continue their unprecedented run

Whether we like it or not, we will find it nearly impossible to ignore the 2020 news headlines, whether political or economic. While the upcoming election and impeachment news will inevitably bombard us at every turn, I will mostly be interested in economic news and whether this unprecedented run we have experienced in the markets is sustainable. The S&P 500 is already up over 3.0% thus far in 2020, but three weeks in January do not a year make, especially in an election year.

While I remain optimistic that we will not have a recession this year, I still expect greater market volatility and remain cautious. Maybe that is one of the things I like most about multifamily assets, as they are more of a longer-term macro bet on housing and demographics, which I find

easier to evaluate and predict than what the equity markets might do this year. Regardless, no matter what 2020 brings, we will stay the course, remaining the best stewards we can be for the capital you have entrusted with us. Finally, for those reading this newsletter for the first time, feel free to contact us at clearcapllc.com if you would like to be added to our mailing list. You will receive all future newsletters and information on any future investment offerings.

Thank you, again, for your support, for which we are profoundly grateful.

Best,

Eric Sussman

Founding Partner