“Microeconomics concerns things that economists are specifically wrong about, while macroeconomics concerns things economists are wrong about generally.”

-P.J. O’Rourke

“Bull markets are a hell of a lot more fun.”

-Anonymous Managing Director, Merrill Lynch

According to Wikipedia, where I learn everything worth knowing (sorry ESPN, Twitter, and Truth Social), I have recently come to understand that New Year’s resolutions originated over 4,000 years ago in ancient Babylon during a 12-day festival known as Akitu. The tradition was subsequently adopted by the Roman Empire and then by knights in the Middle Ages, who would renew their vows to chivalry at the start of any year. Meantime, I know many of you are intimately familiar with Rosh Hashanah, signifying the Jewish New Year, which in on-brand messaging, marks the holiday with ten days of repentance, culminating with Yom Kippur, a day of fasting and prayers of atonement for past year’s transgressions.

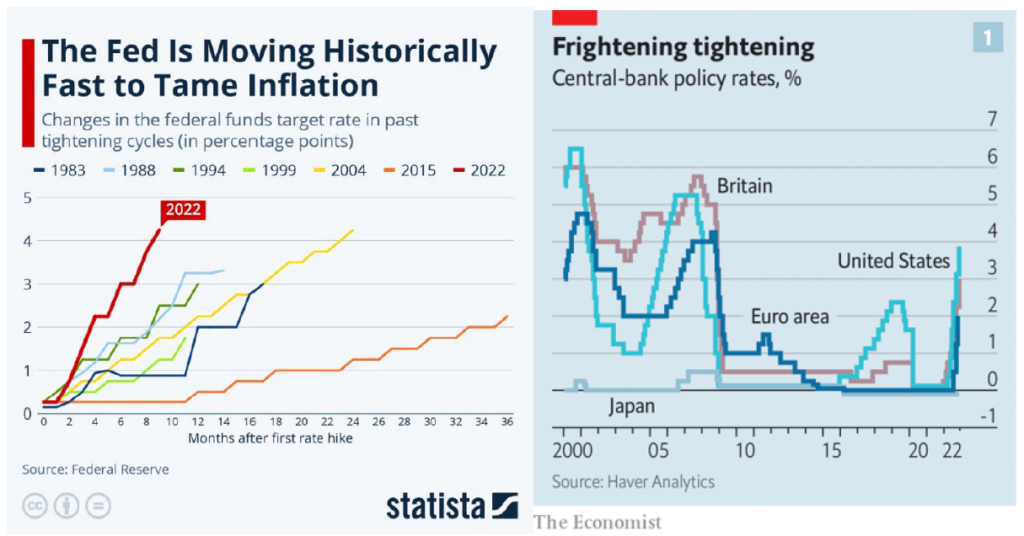

Therefore, I wish to start the inaugural 2023 quarterly newsletter with more than just a perfunctory “Happy New Year” and expression of well wishes for 2023 (which I want to pass along, of course), but with a sincere mea culpa for getting the 2022 inflation and interest rate story so wrong. While I expected inflation and interest rates to increase under less accommodative Federal policies and that wages and rents would roughly keep pace, providing a reasonably inflationary hedge, I certainly did not expect the Fed Funds rate to rocket from 0.00 to 0.25% at the start of 2022 to 4.25-4.50% by the end of the year, following an unprecedented seven rate hikes in a single year.

As a result, there was and is simply no way that wages, rents, and ultimately, the operating cash flows for virtually any asset (e.g., equities, fixed income, and residential/commercial real estate) could keep up with such a sudden increase in the cost of debt, especially since we (and others) so often use variable-rate debt in concert with value-add strategies. Even though that debt is hedged via interest- rate caps, rates moved up so sharply and quickly that we are now paying the maximum hedged interest rate on virtually all of our floating-rate debt. The pain is not inconsequential.

One silverlining is that lenders are requiring us to set aside funds each month to purchase replacement rate caps if we continue to hold the current loan subsequent to expiration of the rate cap. We are looking to utilize more fixed rate agency or bank financing while maintaining exit flexibility in future offerings.

Perhaps there is safety or comfort in numbers, as every single economist surveyed by the Wall Street Journal at the end of 2022 got it wrong, but such sentiments represent mixed emotions at best.

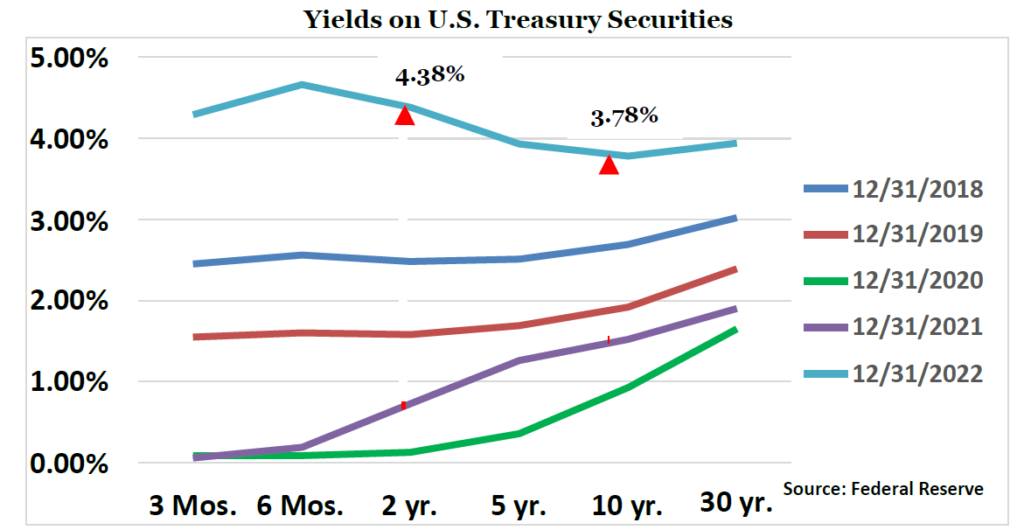

According to “professional” economists (an oxymoron if one ever existed) surveyed in late 2021, the average forecast for yields on 10-year Treasuries at the end of 2022 was 2.04%, with the largest outlier being 2.90%. Oops. 10-year Treasury yields actually finished the year at 3.78%, after peaking at 4.34% in October.

Meanwhile, the yield curve was substantially inverted at year end, with rates on two-year Treasuries exceeding that of ten-year securities by 60 basis points. Imagine that. Those supposedly “in the know” predicted that 10-year Treasury yields would end 2022 at 2.04%, while yields on two-year bonds ended the year at 4.38%. There is no other way to say it than that is one heck of a whiff. If there is a silver lining to the inversion, the market clearly expects inflation to subside, though it may be on the back of a recession.

The last time prognosticators got it this wrong, Buster Douglas was a 42-1 underdog against Mike Tyson, the Soviets were merely slight favorites to beat a terribly overmatched U.S. men’s hockey team in the 1980 Olympics, the “Red Wave” in the midterm elections was expected to materially change the political landscape, and TCU had a fighting chance in this year’s college football championship game. As I have opined many times, prognosticating is one tricky endeavor. I suppose I should not be too harsh on myself. At least I didn’t put Elizabeth Holmes, Sam Bankman-Fried, Barry Minkow, or Ken Lay on the cover of a national publication or anything, believing they were the next Steve Jobs or Warren Buffett, or that Enron was the best company to work for. Yikes.

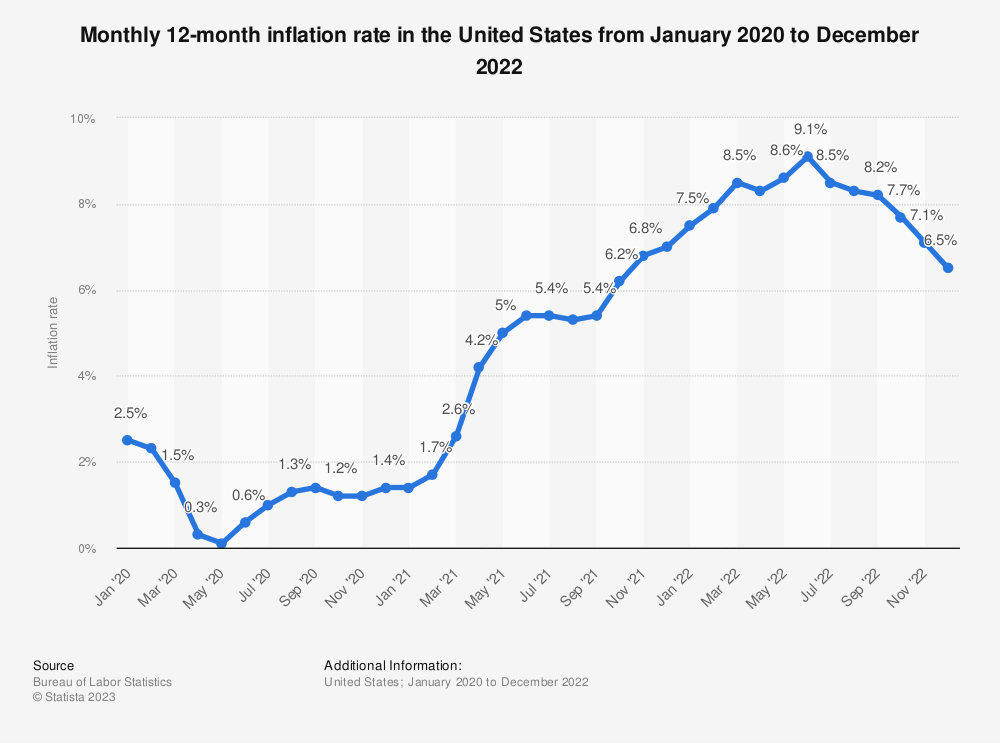

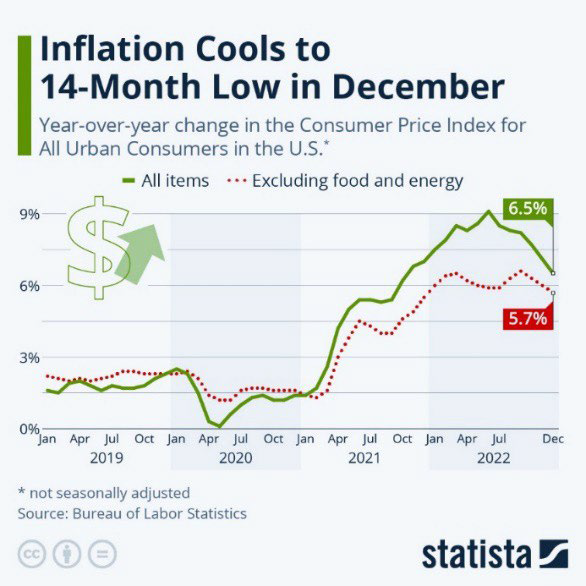

And the culprit for the unprecedented interest rate moves? Well, it’s simply this graph, setting forth monthly inflation rates (CPI-U) in the U.S. between the start of 2020 and the end of 2022. The good news is that inflation appears to have peaked and inflation rates have started to drop, declining each month since the middle of last year. What happens to this graph is quite likely the single most impactful unknown as we look forward to the financial and real estate markets in 2023 and beyond. Despite my misgivings, I will provide my inflation outlook in short order and will do so, knowing full well I might end up yet again with a face full of eggs. And given the recent price of eggs, that would be costly.

In response to inflationary pressures and the Fed’s aggressive responses, 30-year fixed rate, single- family mortgage rates more than doubled last year, from 3.05% at the end of 2021, to 6.42% at the end of 2022. Keep in mind that mortgage rates were even higher just a few months ago, reaching a peak of 7.2% in October, so as inflation has dropped since the summer, so have mortgage rates.

Needless to say, rates on multifamily and other commercial real estate debt moved up similarly, as have spreads, the margin over underlying indices that lenders use to “price” loans and the cost of debt. Higher rates and higher spreads are one of those double-whammies and, though I am not entirely sure what a whammy is, I know that even a single one is not good.

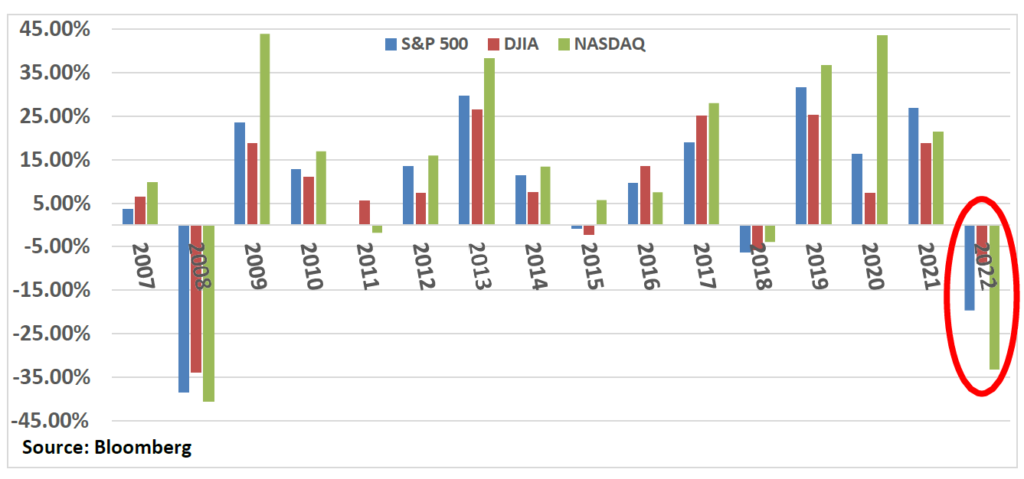

The result? Ugliness wherever one looks, as stocks recorded their fourth lowest annual return in half a century, with the S&P 500 down nearly 20% and the tech-heavy Nasdaq down by nearly a third.

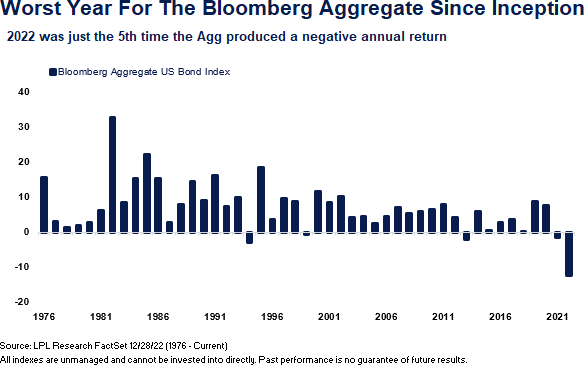

For the first time in 150 years, both U.S. stocks and long-terms bonds were down more than 10%. During the fourth quarter stocks seemed to be stabilizing in October and November…and then came December. The S&P 500 and NASDAQ were down nearly 6% and 9% alone in December, after positive returns in the prior two months to start the fourth quarter. So much for a Santa rally.

Apparently, Rudolph and team went on strike, or his nose ran out of batteries.

To nobody’s surprise, the stocks that have taken the most significant body blows are the previous highflyers, the ones which rarely, if ever, reported profits or generated positive cash flows, and whose entire business models remain suspect (e.g., Peloton, Roku, Affirm, Carvana, Coinbase, Spotify, Zoom). Indeed, the ones that Jim Cramer touted bigly with a routine “booyah,” when the cost of capital was near zero and investors seemed convinced that these firms would be long-term disruptors. Can I get another “oops”?

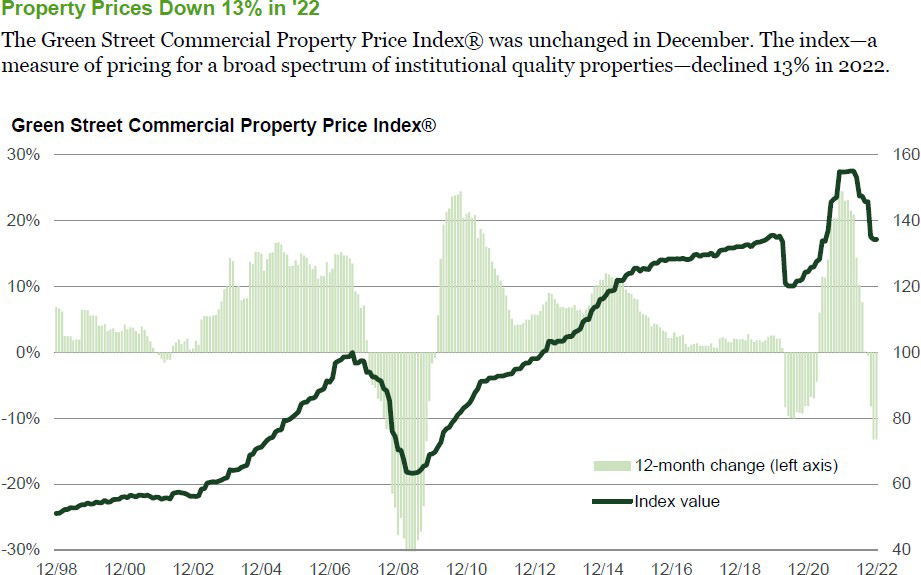

Regardless, the reality is that there was no place to hide in 2022, including real estate. The FTSE NAREIT Index, an index of publicly traded real estate investment trusts, was down roughly 23% in 2022. The best performing segment of publicly traded REITs was hospitality/lodging, down “only” 15.3%. Keep in mind that hotels can change rental rates daily in response to inflationary pressures

and travel significantly rebounded last year. Meanwhile, residential REIT prices were down 31.3% in 2022 and according to Green Street Advisors, commercial property prices overall (public and private markets) fell 13%.

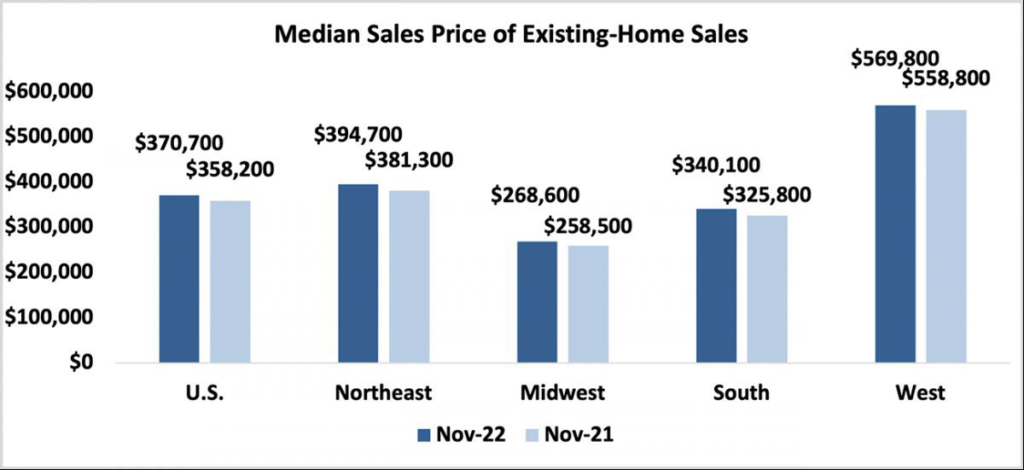

More granular results were fairly predictable. Existing home sales tumbled, down over 35% through November (year over year), while home prices themselves were down only modestly, about 5% on average, across various swaths of the country and different price points. This was one prediction I got mostly right, that higher interest rates would significantly reduce transaction volumes, but pent-up demand, persistent undersupply, elevated money supply and liquidity, the relative health of banks, the availability of mortgage capital, and continued (albeit lower) institutional investor interest in the space, would prevent what would be the worst sequel in history, the Great Financial Crisis, Part II (barely beating out Caddyshack II and Jaws: The Revenge).

Here is the data (through November) in all its…splendor:

And the multifamily market? Was it able to buck the trend?

In a word, “no.” While multifamily assets should and generally do perform better in inflationary environments than other real estate assets encumbered with longer-term leases and stickier short- term cash flows, residential rents (like all rents) simply could not keep pace with the Federal Reserve’s gravity-defying interest rate moves. And to make matters more challenging, recession fears, general economic and political uncertainty, and the additional supply of units to several markets, have resulted in a recent softening of rents in most markets, a reversal of trends witnessed in recent years.

While I believe these challenges and headwinds are transitory and will provide some very favorable buying opportunities, they will create operational and financial challenges in the interim, as bear markets inevitably do. That is, the longer-term fundamentals supporting multifamily investments remain squarely intact (e.g., affordability, supply of single-family homes, demographics). However, if asset managers and private equity firms are prudent and conservative, they will likely reduce distributions, manage controllable expenses more carefully, and postpone capital projects with uncertain ROIs until inflation abates, markets stabilize, and visibility becomes less uncertain, likely during the latter part of 2023. We are certainly doing so and I was hardly surprised when Blackstone recently announced that it would “curb” investor withdrawals from its behemoth $69 billion REIT.

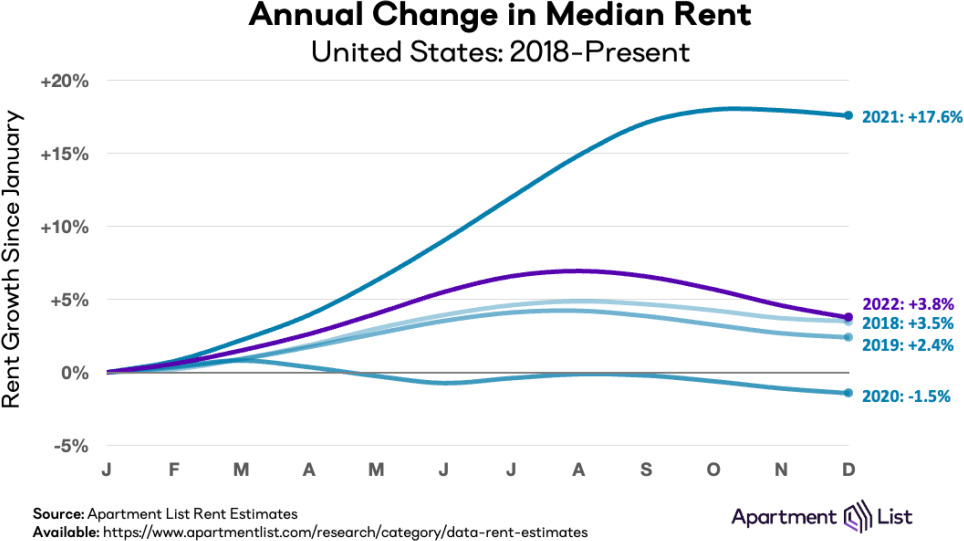

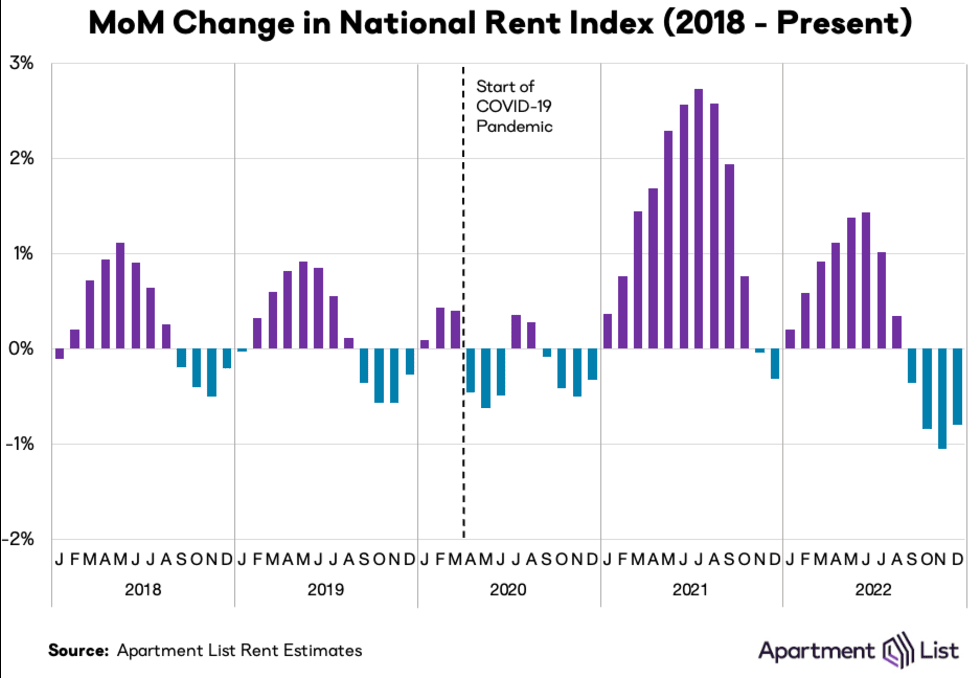

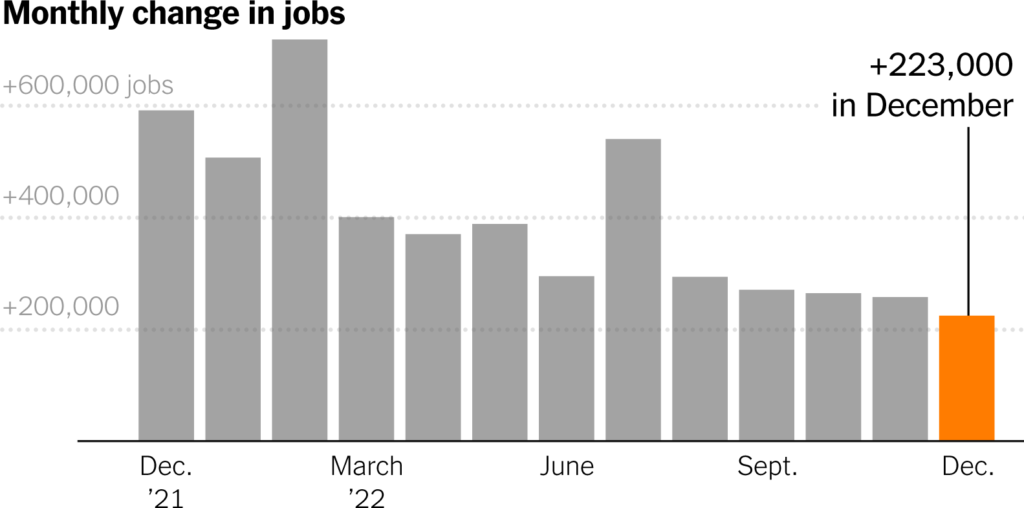

A few pictures communicate a thousand words with regards to the multifamily markets. While national rents increased 3.8% in 2022, the annual figure masks a more sobering reality that rents actually declined in each of the last four months of the year. For example, rents in December 2022 were down 0.8% nationally. The reality is that 2021’s overall multifamily rental growth of 17.6% was simply remarkable and unsustainable and so it is not shocking that rental growth in the 40 largest markets has softened during the past year.

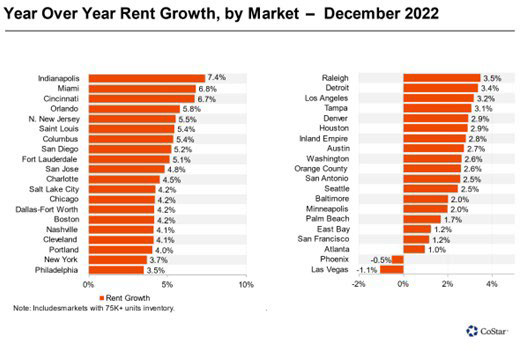

For example, in Palm Beach, rental growth declined from 30.4% in 2021 to 1.7% in 2022, still positive, but barely so. Phoenix and Las Vegas, markets that witnessed 20%+ rental growth in 2021, saw rents decline year-over-year. And 2022’s Oscar winner for “greatest year-over-year rental growth?” Indianapolis, at 7.4%, followed by a number of other Midwestern markets, including hotspots Cincinnati, St. Louis, and Columbus. Last year’s top 10 list for rental growth was over- represented by cities in the Midwest, after the Southwest and Sunbelt were overrepresented in prior years. Is it “what goes up, must come down” or “what does not go up as much as others, must eventually catch up?”

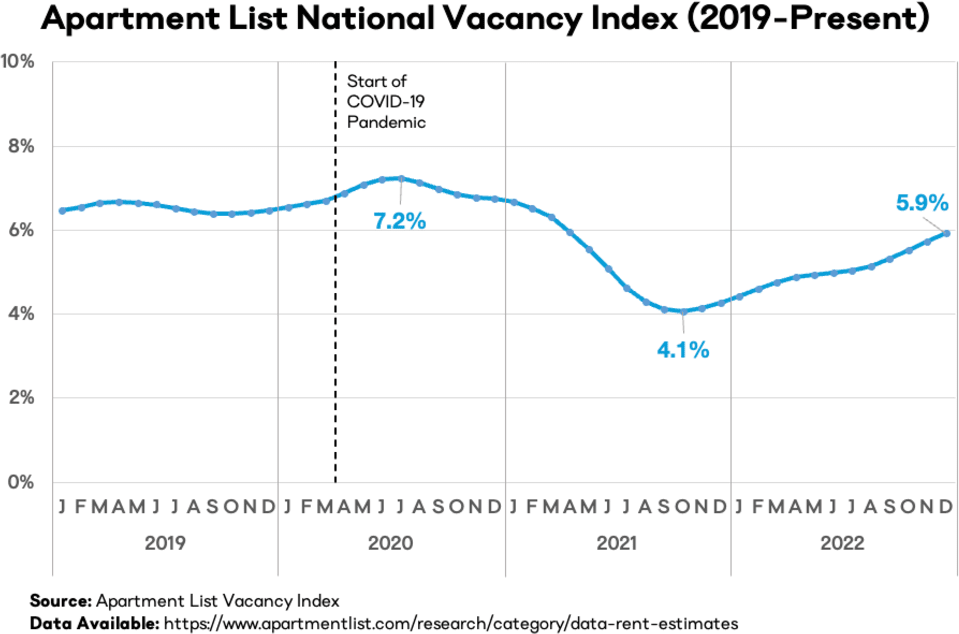

In short, the fourth quarter was a challenging one for multifamily investors and asset managers, on top of an otherwise challenging year of inflation and higher capital costs, as limited absorption (net units rented) and new demand ran headfirst into the reality of nearly 100,000 new units delivered to the market nationally, increasing the national vacancy rate from 5.7% at the end of the third quarter to 5.9% at the end of 2022. And I am not even counting the housing that Elon Musk created when he converted some of Twitter’s offices into temporary bedrooms, causing some to quip that Musk is the first person to add housing to the Bay Area in years.

In short, 2022 was already likely to be challenging, if just by comparison to 2021, before Russia - in what has to be considered an extraordinary and historic strategic blunder - invaded Ukraine and China decided it would be better off shutting down its economy to stymy Covid rather than treat its population with western vaccines. Throw in a spoonful of financial fraud (FTX/Alameda Research) and a pinch of domestic political chaos (heck, I was willing to become Speaker of the House last week) to a gallon of inflation and Federal Reserve tightening, and you have a Michelin-starred recipe for a bear market and significant declines in asset values. 2022 was truly the flip side of 2021, where almost any investment strategy worked, and all asset classes saw healthy returns. Markets can indeed be and are fickle things.

So, what’s the broad economic outlook for 2023? Will market values recover? Inflation and the Fed? Recession or…?

One might think that being once bitten, I would be twice or perhaps three times shy in making predictions for 2023, but old habits die hard, I suppose. Maybe I am just like that proverbial broken watch, right twice a day. I am also an optimist by nature, believing that market downturns inevitably create opportunity for longer-term, patient investors, perhaps because they do.

To cut to the chase, I expect 2023 to be a year when the markets find their footing and, during the second half of the year, recapture all of 2022’s losses, perhaps a recurrence of what happened in 2009 following 2008’s significant market declines. Inflation will continue to retreat as the economy softens and the impact of higher interest rates and capital costs take their toll. The markets will respond favorably to lower inflation prints and the end of the Fed battering ram. Residential and commercial real estate rents will decline across nearly all markets during the first third or half of the year, before recovering, repeating what we witnessed during and subsequent to the Great Financial Crisis and other downturns over the past couple of decades.

While a 2023 recession seems a real possibility, I am not convinced that one is unequivocally in the cards. For one thing, according to a recent survey of public company CEOs, over 90% felt that there would be a recession this year. I am not nearly convinced that CEOs are more accurate at forecasting than professional economists, though one would expect that they would have better information and insights as to current demand and backlog. The contrarian in me tells me that when there is that sort of consensus, something else is likely to happen. Secondly, global GDP was up 1.3% through the third quarter of 2022, and while these numbers are nothing to crow about, they are not horrible given all the headwinds the world economy has faced and they do show growth, albeit modest.

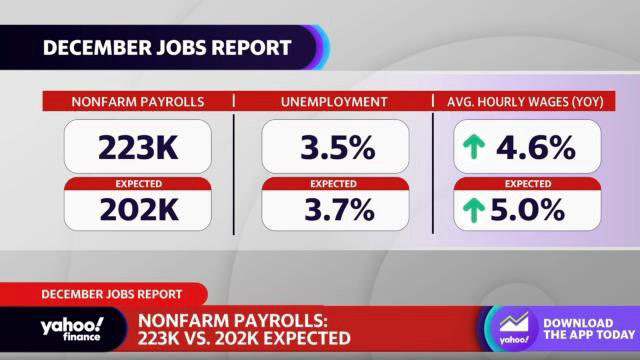

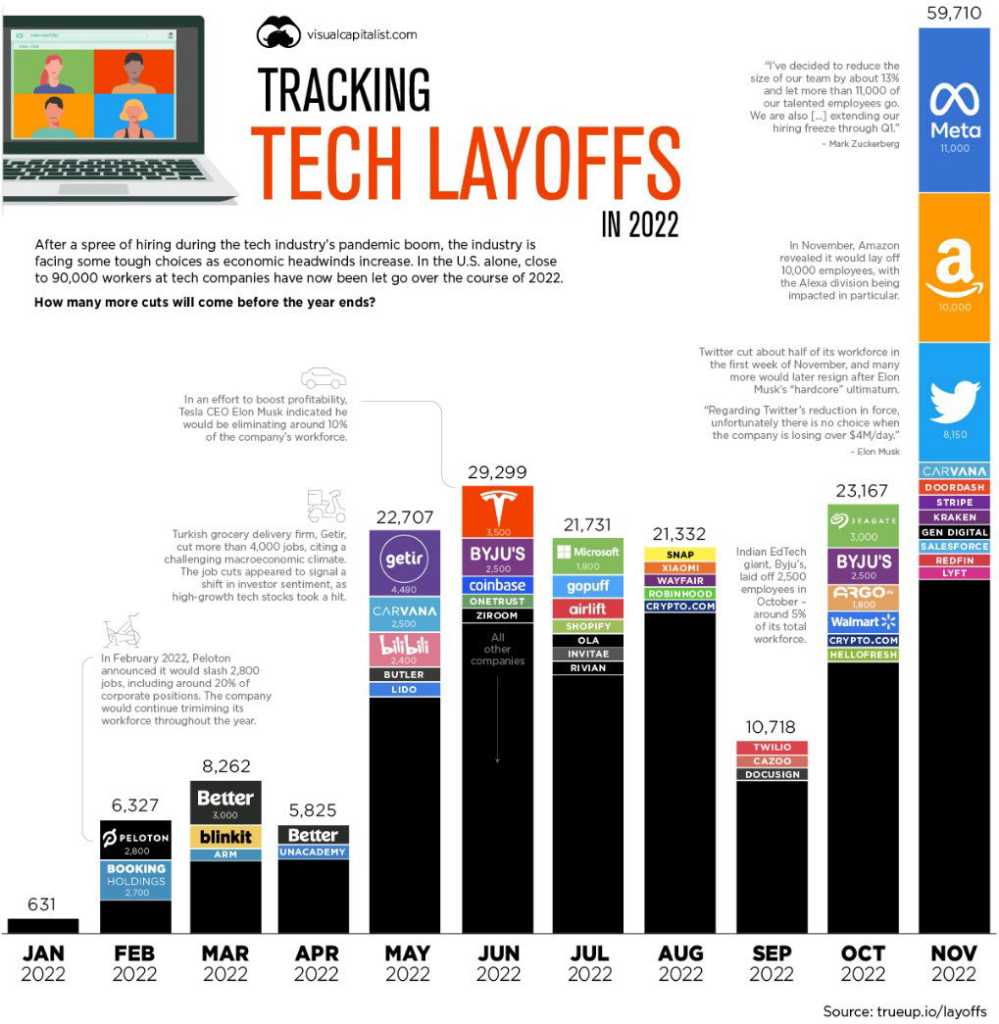

In addition, while layoffs have accelerated of late, unemployment remains low and the job market fairly robust, even in the face of higher inflation and a broader economic slowdown. While tech firms are laying off increasing numbers of staff, Main Street is acting as a job sponge and is still facing challenges attracting and retaining talent. Job losses at Amazon, Twitter, Meta, Microsoft, and Salesforce have thus far been offset by employment gains in leisure/hospitality, healthcare, and other service industries. In December, employers added 223,000 jobs, above the 200,000 estimates, though these results represent the smallest job gains in two years. Average hourly earnings were up 4.6% year over year, down from March’s peak of 5.6%, and below more inflationary expectations (5%). The wage gains were the most modest since mid-2021.

Some articles have announced the tech layoffs with attention-grabbing headlines, as though these headcount reductions represent the “end” of an era in Big Tech, as the Washington Post crowed in mid-November, with a tagline that the layoffs are “stoking memories of the dot-com crash 20 years ago.” Please. Nothing like a dash of journalistic hyperbole to accompany your morning latte. Sure, Amazon, Meta, Microsoft, Netflix, Alphabet, Twitter, and Apple are trimming some fat, but they aren’t going anywhere and future technological breakthroughs in everything from virtual reality to artificial intelligence to health care will prove significant future job creators.

Meantime, consumer confidence has rebounded off its summer lows, as have the equity and bond markets. In fact, the S&P 500 and NASDAQ are up 4.2 and 5.9%, respectively, during just the first two weeks of 2023. And in one last data point, the staff tending the front desk of the spa at the ARIA casino in Las Vegas told me they were swamped and completely booked when I asked just a few weeks ago during a visit and was on my way to the gym. Thus, consumers are clearly still spending on discretionary items, at least when it comes to shiatsu and aromatherapy, according to the SSBI (Sussman Spa Bookings Index™).

However, we should keep in mind that residential and commercial real estate comprises some 20% of U.S. GDP. Housing’s combined contribution generally averages between 15 and 18% of our economy and includes construction of new single-family homes (including manufactured ones) and multifamily projects, residential remodels, and brokerage commissions. Perhaps it is as simple as one of my UCLA Anderson colleagues, Ed Leamer, wrote in a 2007 paper, “the housing cycle is the business cycle.” Meanwhile, according to another study I recently read, commercial real estate (think office, retail, industrial) contributes another five percent to our GDP each year.

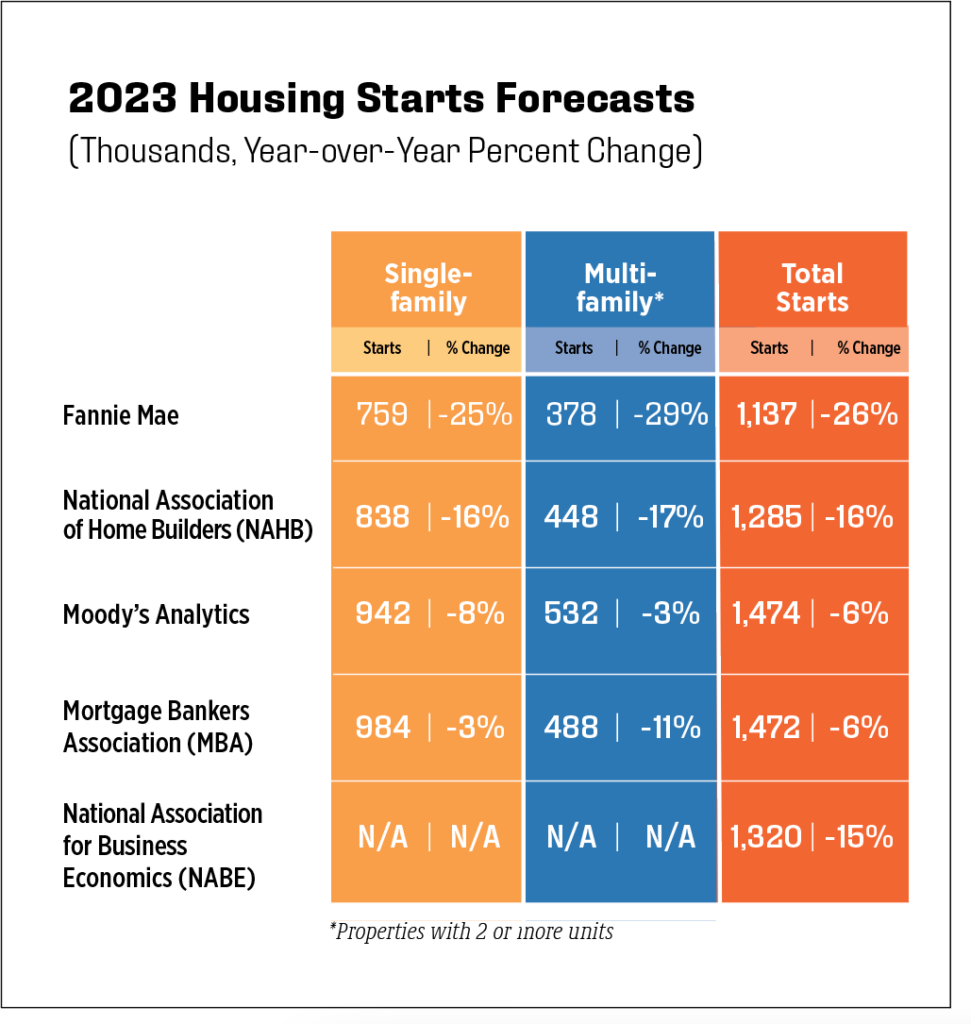

In short, one does not need to be a psychic, economist (professional or merely rank amateur), market pundit or guru to recognize that sharp declines in residential and real estate transactions and declines in new housing starts and permits issued will translate to significant economic drags in 2023 and perhaps beyond. In addition, in my last quarterly update, I predicted that declines in the housing market - purchases and sales and housing starts - would present considerable headwinds to companies whose results are closely tied to the housing cycle. The recent rumor that Bed, Bath, & Beyond will be shortly filing for bankruptcy could be Exhibit A in this regard. I expect other firms to follow or significantly underperform (e.g., Wayfair, Williams Sonoma). This simple chart speaks volumes, indicating that housing starts are expected to decline sharply in 2023, regardless of who is doing the forecasting.

The worst of inflation appears behind us (can I get a “hallelujah”?), but the question remains as to where it might find its equilibrium, and will that equilibrium approach the Fed’s two percent target? At this point, I see more deflationary pressures in the U.S. economy, though energy and food prices are challenging to predict. Between significant declines in nearly all asset values (e.g., equities, bonds, real estate), the recent retreat in crude oil prices (back below $80 a gallon from over $100 this past summer), December’s historic 15% decline in used car prices, and the overall 0.1% decline in December’s CPI-U from November, evidence of deflation is not hard to find.

In early December Kroger’s CEO indicated that food inflation was “easing” and in fact, food prices declined modestly in December, down 1.9%, according to the FAO Food Price Index, while overall food prices were up 10.4% last year. Of course, one might not believe the data based on the price of eggs, where not just the sunny side is up. Egg prices were up 60% in 2022 and over 11% in December alone. Finally, in perhaps the most probative data point surrounding inflation, I recently read Sam’s Club recent earthshaking announcement that it has cut the price of its in-house hot dog and soda combo to $1.38 from $1.50, undercutting Costco! Of course, the last thing I need is additional motivation to consume more hot dogs.

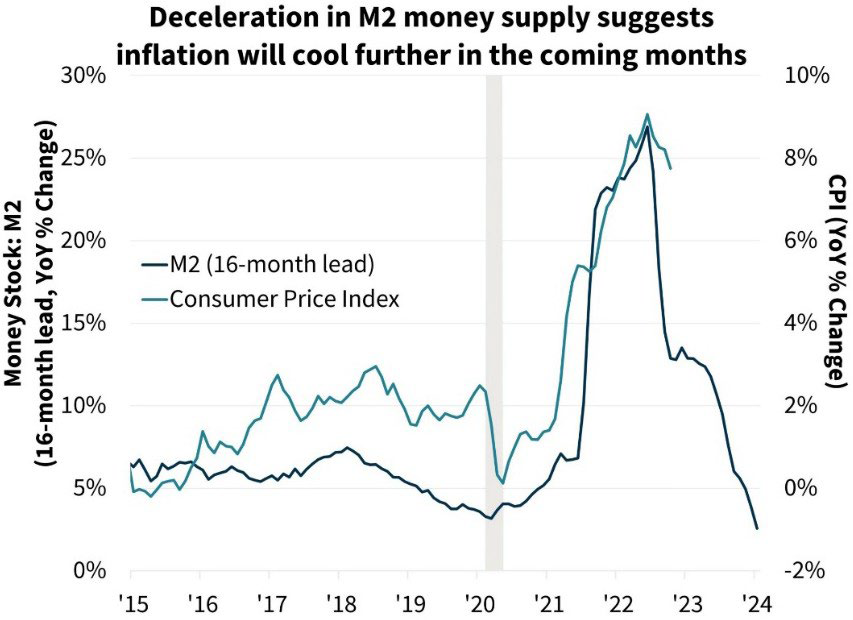

Money supply and bank lending activity also provide compelling deflationary evidence

Over the past few quarters, I have mentioned that tremendous sideline liquidity – some $22 trillion in M2 money supply – provided a significant downside buffer to sustainable market declines and support for my contention that once markets stabilize and fears of recession abate (or a mild recession ends), that liquidity will find its way into the markets, driving prices back to previous levels. However, in recent months, there has been a modest decrease in money supply, consistent with deflationary pressures.

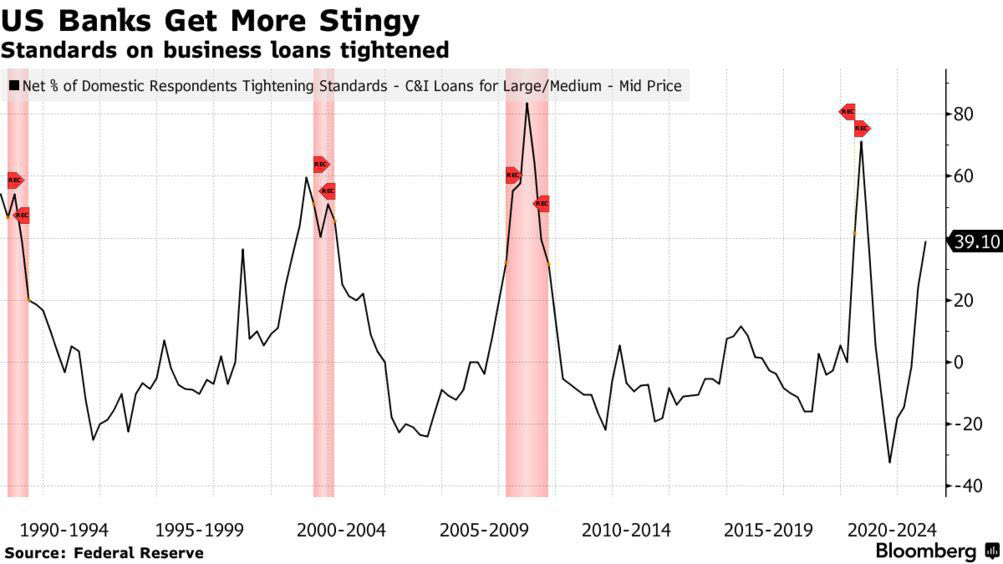

In addition, U.S. banks have tightened underwriting standards for business loans, consistent with what we are witnessing in multifamily real estate lender underwriting. Stingier loan underwriting is deflationary, at least on the margin.

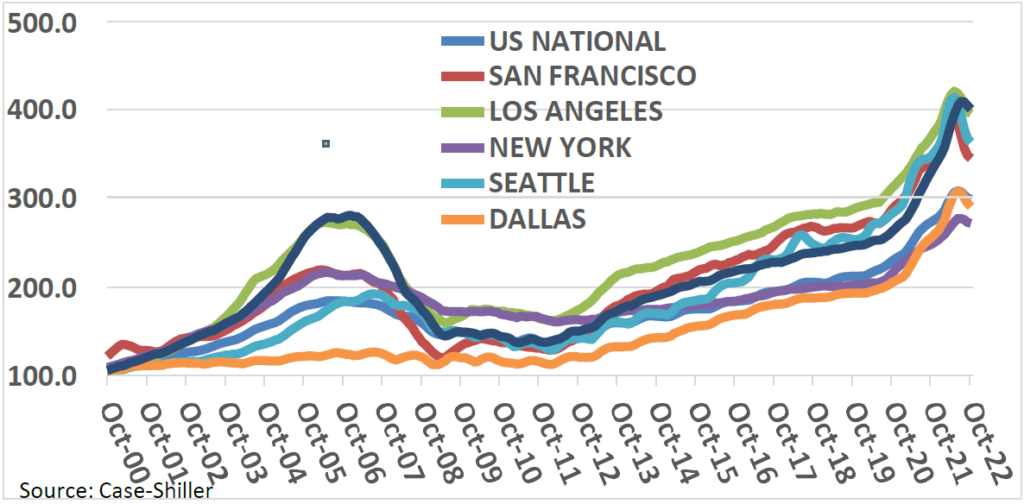

The unprecedented run we experienced in housing prices and rents between 2010 and the end of 2021 is clearly taking a pause. The days of multiple offers, many waiving contingencies, offering significant non-refundable deposits, and/or others accompanied by pictures of families and cute pets, are likely over, at least for this cycle. As mentioned, single-family home prices are generally down about 5% nationally, and according to a recent article I read, about 8% of homes bought in 2022 are under water. Certain markets, principally those that defied gravity in recent years (e.g., Boise, Phoenix, Atlanta, Austin) and witnessed prices of single-family homes rise nearly 60% or more between 2012 and 2019, are down more sharply.

For example, according to Redfin, housing prices in Austin and Boise declined by over 3% and 2% in December alone, respectively, and homes were taking over two months to sell, twice as long as last year. In another example, the median home price in Sacramento, where Clear Capital owns two assets, the median single-family home increased 40% in value between March of 2020 and the end of June 2020, reaching a median of $560K. More recently, the median home price has dropped to about $510K, a modest (10%) retracing.

How long the housing slump lasts remains to be seen, but I anticipate that rents will decline modestly over the next year and then begin to rise again, recapturing previous highs, similar to what we witnessed during and subsequent to the Great Financial Crisis. Keep in mind that a new study released by National Multifamily Housing Council and National Apartment Association indicated that we need to build 4.3 million new apartment units by 2035, just to meet demand.

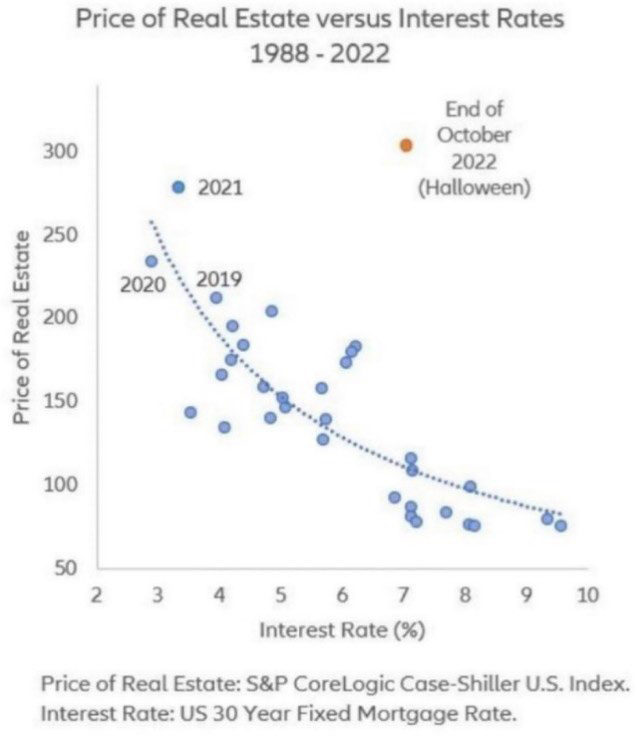

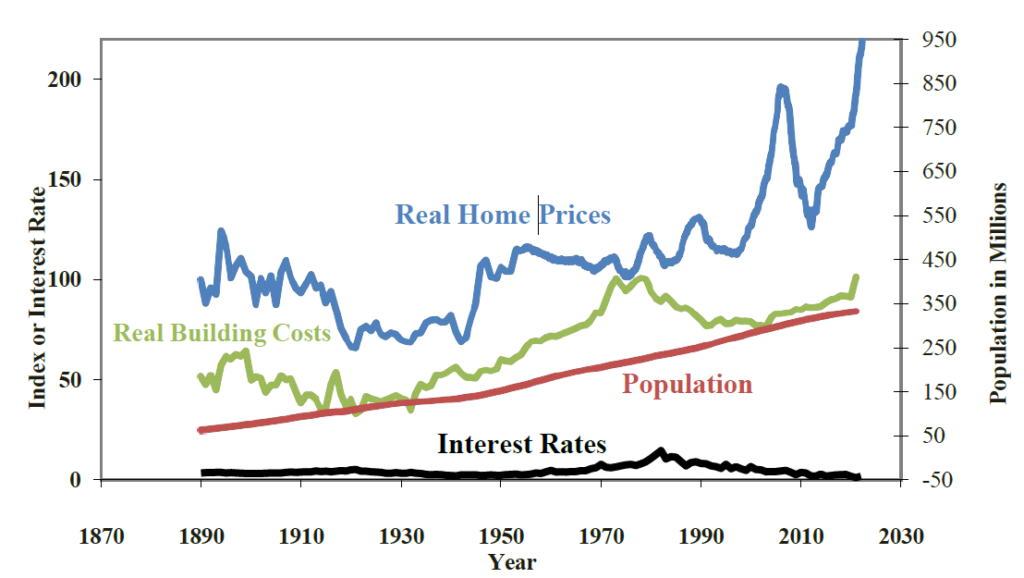

However, the data is conflicting. On the one hand, graphs like those below seem to indicate that housing prices may be poised for further declines, if just because they appear at significant odds with historical norms, whether comparing them to interest rate levels (first graph) or other factors including population growth (second). Both graphs are sourced from Robert Shiller, of Yale and Case-Shiller fame.

However, as discussed in previous memos, this time may, in fact, be different, as a result of everything from Covid and pent-up demand, a lack of single-family supply, institutional involvement in the single-family market, and excess liquidity. Moreover, three other important data points provide support for the contention that significant declines in housing prices are not in our future.

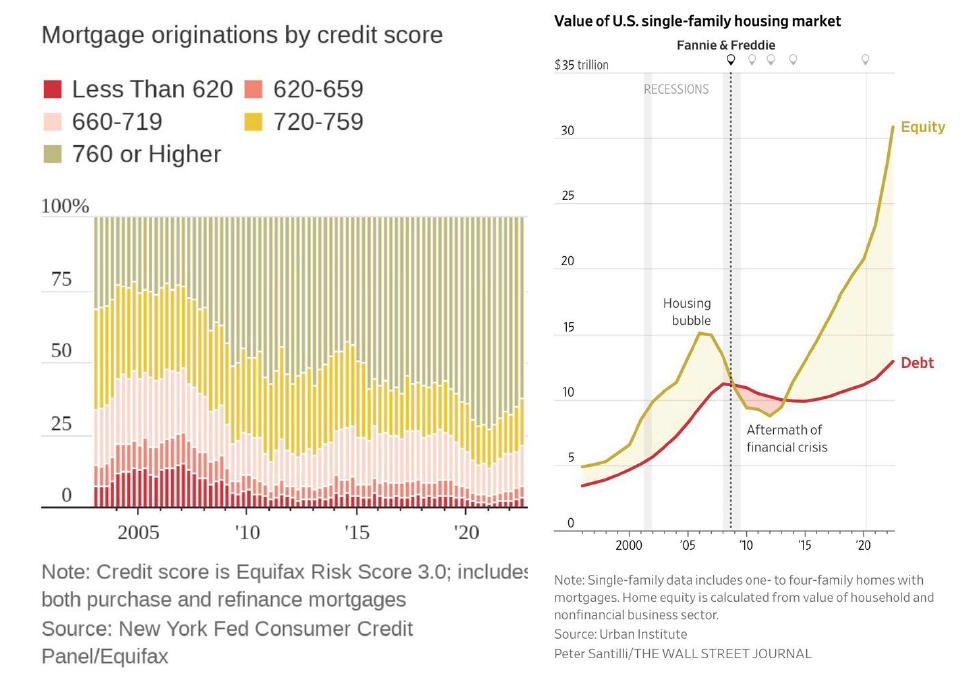

One, banks have exercised far greater underwriting discipline in recent years, such that more than half of borrowers have credit scores of over 760. Two, the collective amount of equity homeowners own in their homes exceeds $30 trillion, a record high, and a very different reality than what we witnessed during and following the Great Financial Crisis. Finally, as discussed in the last quarterly memo, banks are in decent financial shape and not excessively levered generally, with excessive exposure to the single-family market.

In short, I expect the housing market, both single- and multifamily, to be fairly soft in the first half of 2023, but to rebound towards the latter half of the year and into 2024, as inflation subsides, interest rates decline, the Fed ends its money-tightening endeavors, and the equity markets stabilize. In the meantime, macro-level themes persist. Single-family homes will remain out of affordable reach for many or even most, driving them to rent, perhaps indefinitely.

Consistent with that premise, I recently read an article in the Wall Street Journal about non-profits getting into the housing game, acquiring single-family homes for cash, and then re-selling them to families at cost, a sort of “activist home flipper.” The particular non-profit and market featured in the article were in Milwaukee, where home prices are far more affordable than countless other markets. But these efforts reveal just how widespread and systemic the housing affordability issue happens to be. However, while these efforts may merely reflect that old adage that “desperate times call for desperate measures,” I cannot fathom that they will be broadly impactful.

Meantime, I am keeping my eye on several other housing-related trends and data points

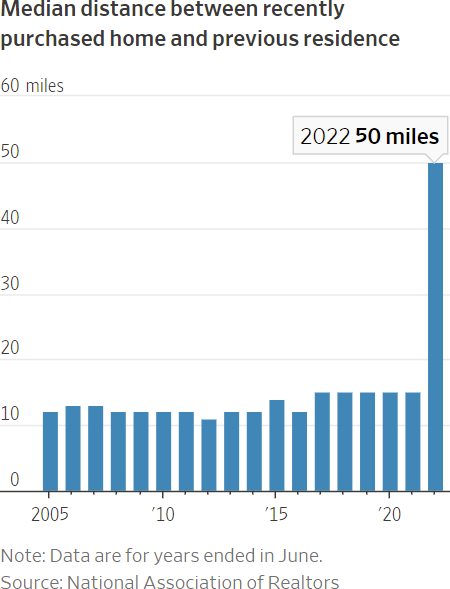

• Homebuyers are moving farther away: In an interesting statistic recently released by the National Association of Realtors, buyers who bought homes during the year ending June 2022 moved a median of 50 miles from where they owned their prior home, the greatest distance on record, literally quadrupling historical behavior, and reflecting an increasing trend over the last five years. Remote work and lower housing prices are compelling relocations and growth in tertiary and quaternary markets, exurbs, and rural markets, trends we have discussed at length previously. The shift explains the explosive growth in markets like Idaho and California’s Central Valley, from Riverside County to North Port, Florida, to Indianapolis. I am reminded of Southwest Airline’s catchy advertising tagline, “You are now free to move around the country.”

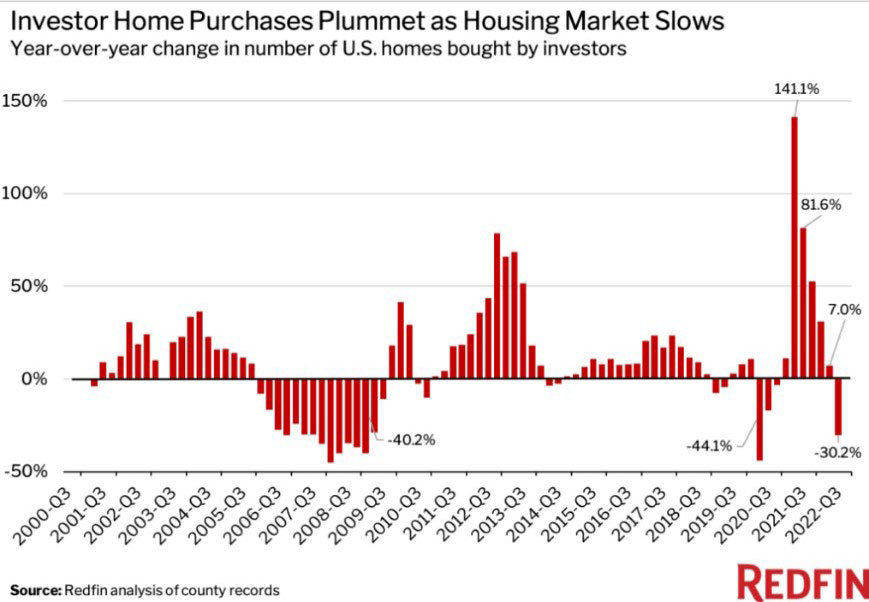

Home sales to investors slid 30% in 2022: In the third quarter of 2022, institutions bought approximately 66,000 houses in the 40 markets tracked by Redfin in Q3, down over 30% from the same period in 2021. Even institutional investors have been reining in their horns a bit in the face of all the economic, political, and market uncertainty. But let’s be clear. They have proven that owning single-family homes as rental units is an investable and scalable asset class for institutions, and I expect they will continue to scoop up homes, new and existing, going forward, competing with traditional homebuyers.

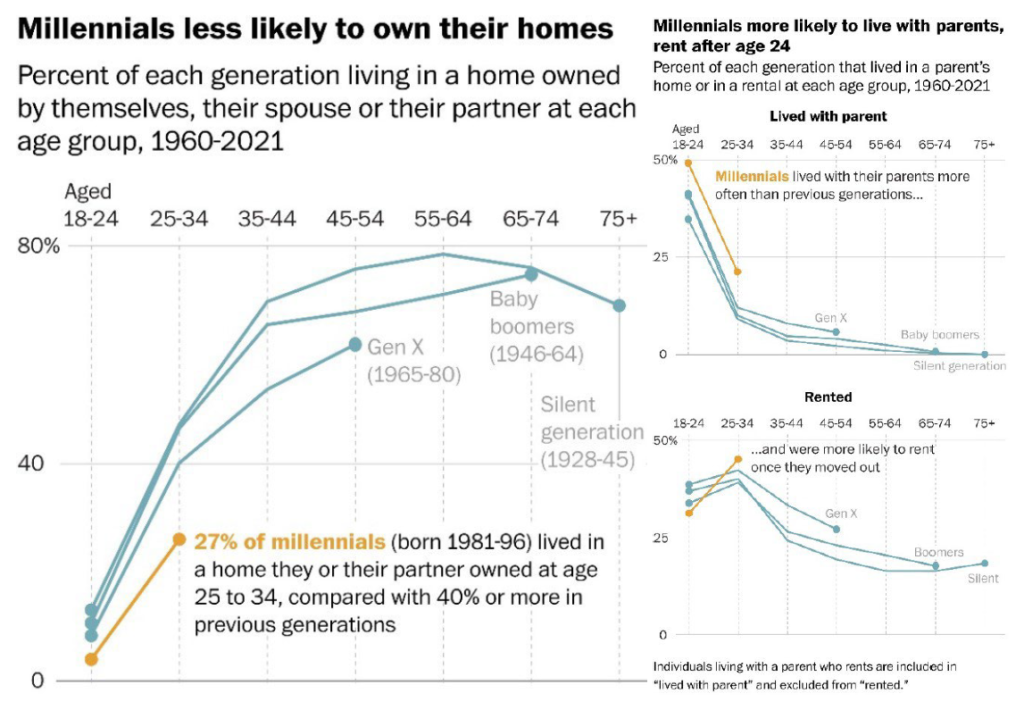

Millennials are much less likely to own their homes: In a data point surprising nobody, millennials are far more likely to be renters or living at home (sorry, parents), and I believe that this trend will persist for the foreseeable future, presenting additional long-term tailwinds to Clear Capital’s multifamily strategy, despite nearer-term challenges.

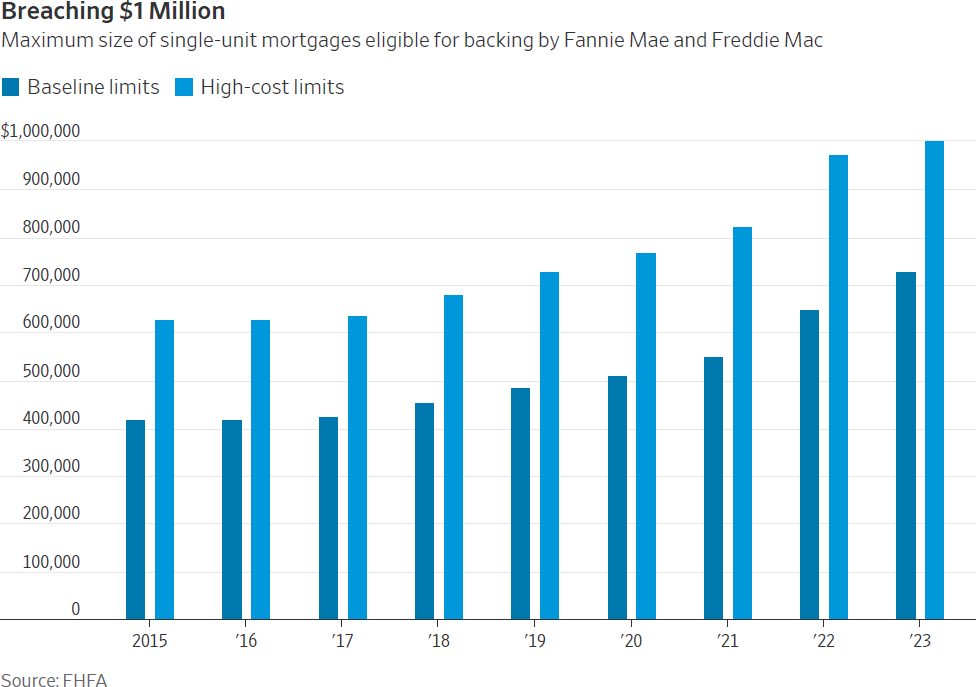

Uncle Sam will start backstopping mortgages of more than $1 million in “high- cost” markets beginning this year: In November, the Federal Housing Finance Agency announced that it will begin to back single-family residential mortgages up to $1 million in certain “high cost” parts of the country, allowing prospective homeowners to secure larger loans with lower rates. In most areas of the U.S., the new limit for “conforming” loans backed by Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac, will be $647,200 for single-family homes, an increase of nearly $100K from the previous limit of $548,250. I don’t think the change will be significantly impactful, but it is a worthwhile data point impacting the housing market.

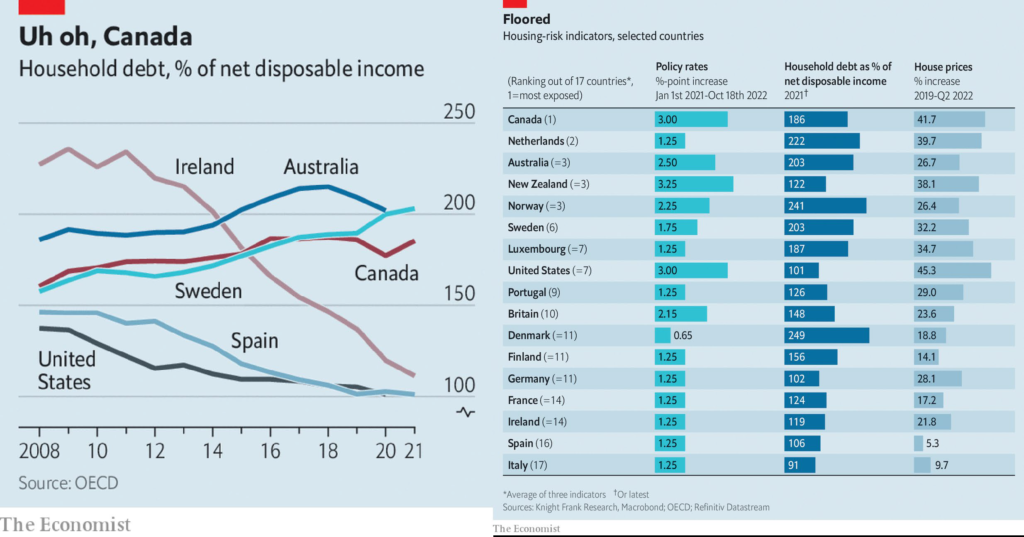

Foreign housing markets, however, are facing even greater pricing pressures, with several markets (e.g., Canada, New Zealand, Australia) experiencing double-digit price declines: Last week I was giving a presentation to a group of corporate real estate folks from Taco Bell, when someone from the audience asked for my views about Canadian real estate markets. I confessed that while I don’t follow them very closely, I had seen some data surrounding single-family homes that made me uneasy. Specifically, several of these foreign markets are far more levered, with far higher levels of household debt. Australia, Canada, and Sweden, in particular, appear at far greater risk than the U.S. or Ireland, for example.

Finally, there are always a few other economic, political, or market headlines or news items that have grabbed my attention and are noteworthy

• Politicians mostly seem to have taken the fourth quarter off: In a welcome break, politicians and other policy makers were rather quiet during the fourth quarter of 2022, perhaps focusing on midterm elections, holiday shopping, and the third season of Emily in Paris. I did read one relevant article, however, which discussed how tax policies surrounding vacant land are creating an unnecessary impediment to the construction of new housing. Specifically, in certain areas (e.g., New York City), tax levies on high-rise housing projects are often higher than on vacant lots. The article focused on one six-acre site next to the United Nations on the upper east side, which is valued at over $100 million and is zoned for 1,500 apartment units but has sat empty for 15 years because taxes on the parcel are minimal. While I am dubious that property or other local taxes could present such a significant impediment to a potentially successful housing project, I have repeatedly spoken and written about how policy makers should focus on economic carrots and incentives to promote housing development and increased unit density.

• The office market is a dumpster fire: Many tech companies that drove demand for office space here and elsewhere as they expanded are now canceling leases and flooding businesses with office space as they downsize. Recently Meta, Lyft, Salesforce, and Twitter have been shedding millions of square feet in the Bay Area (Silicon Valley and San Francisco), New York, and Austin as they reduce headcount and shrink their office footprints. Amazon.com stopped construction in July on new office buildings. About 212 million square feet of sublease space is on the market, a record since CoStar began tracking such data in 2005. The national occupancy rate, about 12.5%, its highest level since 2011, will be heading higher in 2023 as net new absorption will be decidedly negative. I anticipate a large number of office foreclosures this year and next, and I would steer clear of the segment as I fail to see any upside catalysts.

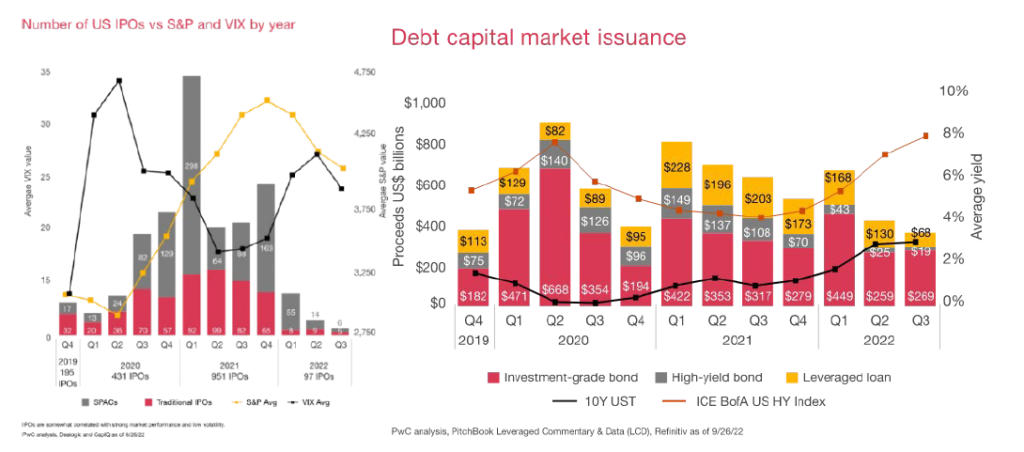

• Mergers and acquisition volume, stock, and bond offerings, as well as angel and venture activity are at their lowest levels in a decade: As the equity and debt markets swoon, Wall Street and their brethren are taking a proverbial breather. IPOs, debt issuances, and venture capital deal volume will likely be taking an extended vacation in 2022, at least until interest rates and markets stabilize. This trend is not only deflationary but will impact virtually all real estate markets and asset classes.

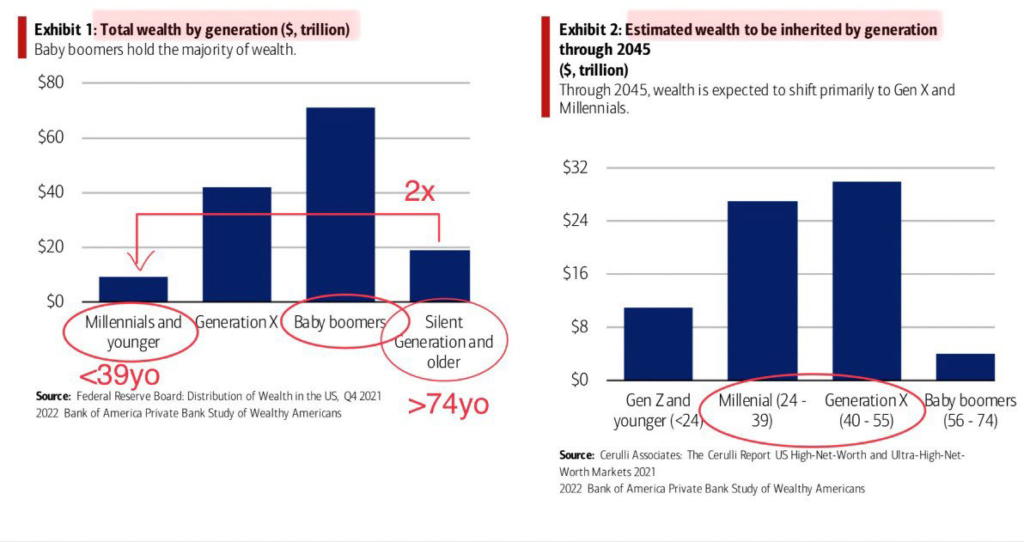

• Over the next thirty years, baby boomers will be transferring tremendous wealth (and real estate) to Generations X and Y: Over the next several decades, Generation X (born between 1965 and 1979/1980), which includes this author, and Generation Y (born 1984 to 1994-1996) are poised to inherit over $28 trillion from baby boomers, those born between the end of WWII and 1964. I can almost hear the long-gone John Houseman echoing a slight twist on that distinguishable catchphrase he popularized in Smith Barney commercials back in the 1980’s: “I make the money the old-fashioned way. I inherit it” (for you, youngins, Smith Barney “earned it.”). The impact of this wealth transfer will be significant, but uncertain. I assume many homes that have not been sold in decades will hit the market as beneficiaries monetize assets, those that they ironically may not be able to afford or even want to own and live in.

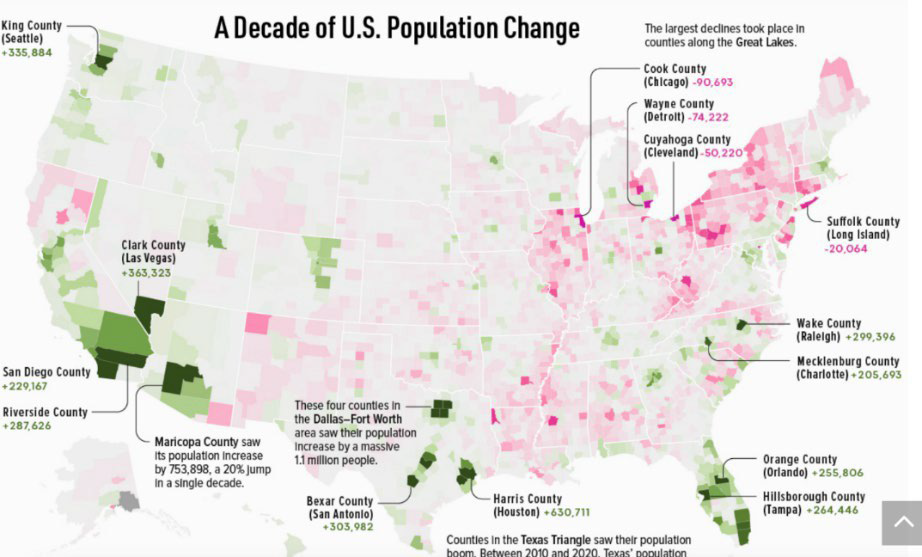

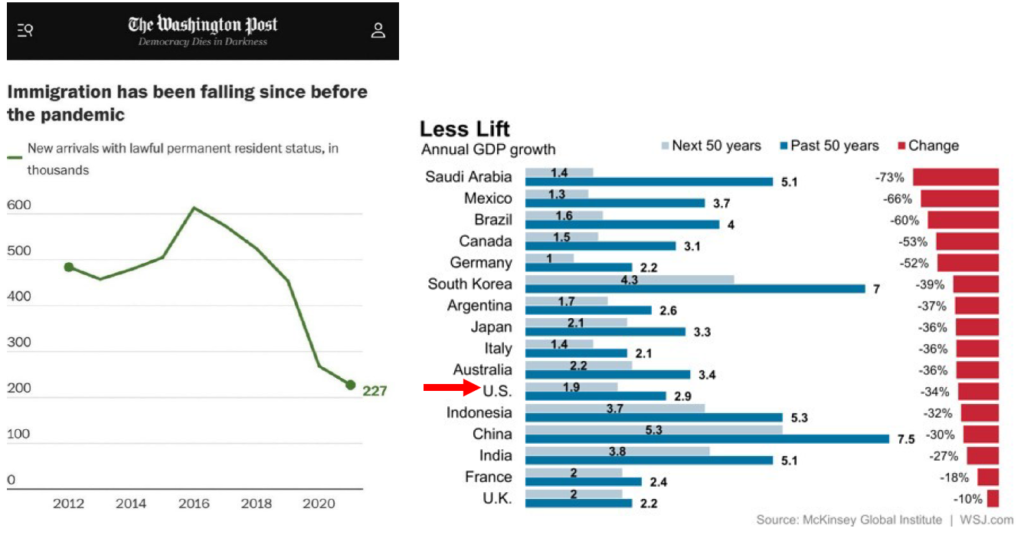

• And lastly, a couple of updates on demographic data and population shifts: During the last quarter, a few articles and data points crossed my desk regarding demographics and population, merely confirming trends we have noted and discussed for some time. One, U.S. population growth remains sluggish, increasing just 0.4% for the year ended June 30, 2022, somewhat better than the 0.1% increase during Covid. Eighteen states lost population, led by New York (-0.9%), Illinois (-0.8%), and California (-0.3%). Population gainers included Florida (1.9%), Idaho (0.8%), South Carolina (1.7%), and Texas (1.6%).

Without immigration reform, the U.S. is destined to experience less economic growth, as I see it. Perhaps it is the lack of immigration policy that results in so many more illegal crossings and border challenges, along with the profound politicization of the issue.

On a related note, China just announced that its population declined last year, falling for the first time in 60 years, reflecting record-low births, consistent with global trends, especially in developed nations. The implications (e.g., economic stagnation, labor supply) are profound and whether China (and others) can reverse the trend remains a significant question mark. I am skeptical and believe that these broad demographic trends (e.g., delayed marriage, declining birthrates) will persist, reducing global growth and inflationary pressures, longer-term.

In conclusion, while 2022 was an entirely forgetful year when it comes to virtually almost anything economic and financial, making predictions for 2023 a bit challenging. However, if history is any barometer, savvy and patient investors will take advantage of the declines in asset values.

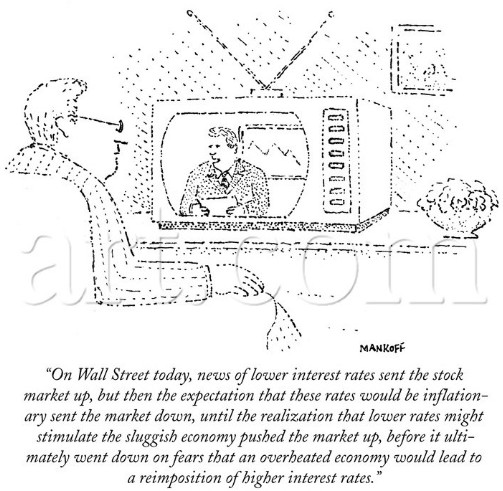

I think this 2012 cartoon from the New Yorker captures the challenges, uncertainties, and conflicting data found in today’s markets as well as any:

However, while downturns and bear markets test wills, abilities, and balance sheets, they inevitably separate wheat from chaff, acting as a sort of survival of the fittest. The Clear Capital team is going to be managing all assets in the current portfolio with even greater focus and prudence, while hoping to take advantage of any dislocation and distress through strategic acquisitions to add to our portfolio. Some of these decisions will create short-term pain (e.g., reduced/suspended distributions, cash-in refinances), but will be necessary to work through a higher-rate, higher-inflation, more uncertain economic environment.

Before ending yet another lengthy quarterly memo, I would like to leave you with a bit of perspective, if not a tad of optimism. While recently trolling folks on Twitter (probably Elon Musk himself), I stumbled upon a letter that Mark Twain wrote to Walt Whitman on the occasion of Whitman’s 70th birthday. In that letter, a true literary time capsule, Twain took the opportunity to identify several inventions that had taken place during Whitman’s 70 years, all in a tone of profound wonderment: the steam press, steamship, steel ships, railroad, cotton gin, telegraph, phonograph, photogravure (crude photography), electrotype, gaslight, electric light, sewing machine, and surgical anesthesia.

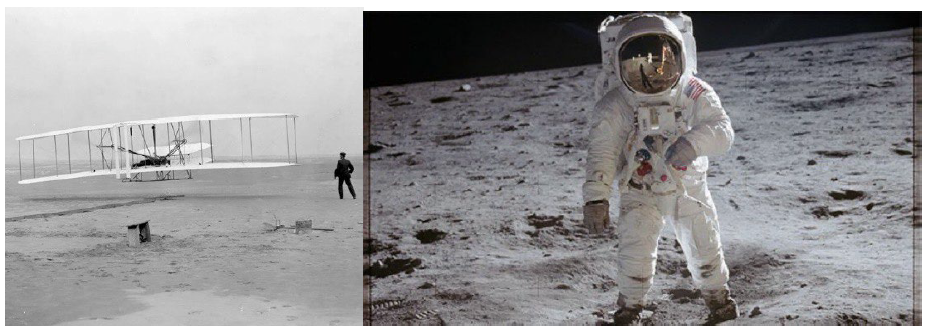

Twain subsequently mentions some of the momentous events that had occurred in that same time period: removal of the French Monarchy, the U.S. Civil War, and the end of slavery. I suppose the point is never to underestimate human ingenuity and progress, and to be profoundly cynical when journalists proclaim the “end of Big Tech” because of an industry slowdown and layoffs. If two pictures can hammer home the point, I give you two, a mere 66 years apart, in 1903 and 1969, respectively:

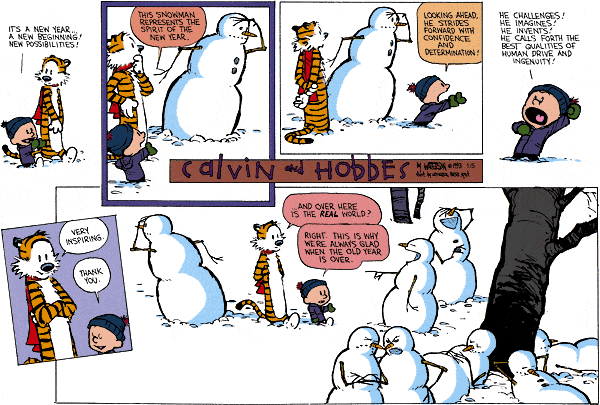

And finally, in what has become an annual tradition in our fourth quarter letter, I would like to leave my final words to Calvin & Hobbes, arguably the greatest philosophers from the last century, and their perspective as to how important it is that we look forward to 2023, closing the curtain on a very challenging 2022.

Before I sign off, I want to invite you my virtual “office hours” on January 24th at 12 PM PST, where I will be chatting about the markets and other economic/political/business news via LinkedIn Live (https://lnkd.in/gKz6T2qJ). We will also be hosting our 2022 Review|2023 Outlook webinar on February 7th at 12pm PST (click here to register), so mark your calendars for both events! And, last, but most certainly not least, I would like to express my sincere appreciation and thanks to you, our investors, supporters, and friends, as well as the entire Clear Capital and Clarion Management teams for their extraordinary efforts over a challenging fourth quarter and year. I remain grateful and fortunate to work alongside each of you.

Best,

Eric Sussman